Interview with Jill Magid – By Geert Lovink

US-American, Amsterdam-based artist Jill Magid was a ‘must see’ at the 2004 Liverpool Biennial (www.biennial.com). Her work fitted in tightly with the Biennial’s topic of the city and the ‘engagement with place’. The installation, Evidence Locker, shown at the Tate Gallery and the Fact centre for new media and screen culture, is a seductive play with Liverpool’s CCTV infrastructure. Instead of portraying citizens as victims of Big Brother, Magid’s works opens up a new field of art and activism in which predictable forms of protest against the almighty eyes of power are turned into a dandy-like performance.

US-American, Amsterdam-based artist Jill Magid was a ‘must see’ at the 2004 Liverpool Biennial (www.biennial.com). Her work fitted in tightly with the Biennial’s topic of the city and the ‘engagement with place’. The installation, Evidence Locker, shown at the Tate Gallery and the Fact centre for new media and screen culture, is a seductive play with Liverpool’s CCTV infrastructure. Instead of portraying citizens as victims of Big Brother, Magid’s works opens up a new field of art and activism in which predictable forms of protest against the almighty eyes of power are turned into a dandy-like performance.

Early 2004 Jill Magid spent 31 days in Liverpool—the amount of time CCTV footage is stored, unless it is used as evidence of a crime. Wearing a red coat she was followed by the CCTV cameras, and an intimate relationship between her and ‘the Observer’ developed. The installation consists of a variety of formats, from a printed daily/exchange with the Observer to audio files of Citywatch employees describing ‘suspect’ behavior of individuals they follow to Jill strolling through the inner city shopping zone. There are two outstanding pieces: one in which the Observer is guiding Jill while having her eyes closed, through mobile phone contact, jumping from one camera to the next. The second one is a short piece, with Jill on the back of the Observer’s motorbike, blurry pictures, switching quickly from camera perspective, until they drive outside of CCTV reach. In the following interview, which was done via email and live at Fact on October 2004, we talked about the Liverpool in relation to Magid’s earlier work and about the responses to this remarkable piece of urban techno poetry.

“(…) I will fill in the gaps, the parts of my diary you are missing.

Since you can’t follow me inside, I will record the inside for you.

I will mark the time carefully so you will never lose me.

Don’t worry about finding me. I will help you. I will tell you

what I was wearing, where I was, the time of day… If there was anything

distinguishing about my look that day, I will make sure you know.(…)”

—Excerpt taken from the Evidence Locker Prologue (Jill Magid, 2004)

GL: The dominant presumption about surveillance is that it turns all civilians into victims. Instead of creating a feeling of security, CCTV systems treat each of us into potential suspects. At least, that’s the common belief. How do you look at this widely shared set of ideas? It’s funny that also political activists, and artists I have to say, have not yet have transcended the surveillance ideology.

JM: I have never looked at surveillance technology from the position of a civilian under its gaze. Or rather I should say that when I have done so, it has been in response to a question such as this. I was drawn to surveillance technology for its potential, as a tool that offered specific qualities and capabilities; CCTV systems enabled me to see and capture myself (and my body) in a form that I could not experience without its employment.

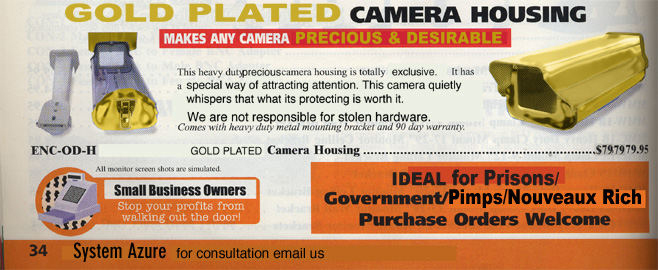

Surveillance cameras create stages, or fixed, monitored platforms. Under their gaze there is a potential for me to act, and a potential to save this act as a recorded event. By watching an area rather than an individual, the camera in its static position seems to favor its context over the pedestrians passing through it. It seems to say: The city is permanent, the civilian ephemeral. In a positive sense, this technology offers me a way to place myself, to become visible (and potentially permanent) within the city, through a medium bigger than myself. It is thus a creative field in which I choose to play. In terms of its political position (as maintaining security or, conversely, invading privacy) I see these positions as qualities of the technology itself- criteria of the tool that simply makes its use, in my way, more loaded. I have also looked at CCTV cameras as objects, or visual signs. In my past project, System Azure Security Ornamentation, I played with the camera’s political ambivalence: between its position as a tool that protects public space as ‘watched space’, or as a sign of watched space. As a sign the camera stands more as a reference to the body or institution that is watching rather than as a tool with the function of securing. I wondered, are the cameras ornamental? And if so, do they signify authority?

I approached Police Headquarters in Amsterdam and asked if I could cover the surveillance cameras on their façade with fake jewels as an art project. They rejected my request and the idea of working with an artist. I remade myself into a company- System Azure- and again approached them with the same question, this time for a fee. After months of negotiations, I succeeded in officially covering four of the Headquarters’ cameras in jewels, in colors with police-assigned meanings. (See www.systemazure.com). Even here I do not feel I was taking sides politically, I was more interested in the camera as an image that triggered questions of meaning, even from those who controlled them.

GL: In your writings for the Liverpool Evidence Locker project you’re talking about the city of L. Everyone will understand you mean Liverpool. Why have you chosen to use an abbreviation? Liverpool is not an average city. It’s quite an extreme and exceptional case, in terms of its history, decline and attempts to revitalize urban life. What’s special about the Liverpool surveillance culture?

JM: Using ‘L’ was not really meant to mask the city’s identity; it was rather a way to place this identity as secondary, or less important. This question reminds me of the first in that both CCTV and Liverpool have their own histories and connotations that are so loaded with preconceived images and critiques that those suppositions come before the story I want to put forth. When I speak of CCTV or surveillance in relation to this piece, or those previous, I try to use analogous terms that are slightly less recognizable: such as spelling it out as “closed circuit video”, or in the book “the camera” or “you” to replace those watching through them. I want to get beyond presumptions of the system, or the city, so that the qualities or details that get less attention-–that, for me, truly make them up- can be for-fronted.

What is special about Liverpool’s system is the criteria it is run by-the 31 day period of holding footage, the laws of the Data Protection Act 1998 (a British act), and the fact of it being so new (the system on this scale is one year old). Some activists based in Liverpool remark that the cameras are symbols of hygienic space, in which “unwanteds” are targeted and removed; or as marketing signs to businesses and consumers that the city is now watched and thus safer. While I may agree with these ideas, the debates around them run parallel to my own questions and desires. I was more concerned with the size of the system and how the presence of so many cameras turned the city into a movie set with 242 cameramen.

GL: For Evidence Locker you have chosen to take up the role as the red-dressed heroine, the seductive female dandy that strolls through anonymous metropolitan areas. In this way the story of urban surveillance systems so to say steps back and becomes an instrument in YOUR story. What does this reversal of functions means to you, compared to the viewers of the installation?

JM: The desire to bring abstract concepts or technologies toward myself in order to understand them intimately is a constant within my work. Liverpool’s CCTV system is extensive, based on complicated legal structures and anonymous as public video surveillance. To come to know it, I needed to use it, to add myself into its equation. I recognized the system’s potential to extend beyond its prescribed intentions. For me, this potential was romantic: I could be embedded into the city’s memory for seven years; the city could be my stage; I could perform and be watched. If what I created was not my story, but someone else’s or that of an invented character, I would not have been able to feel it in the same way. Only by being watched, and influencing how I was watched, could I touch the system and become vulnerable to it.

I designed the two installations, Evidence Locker at Tate and Retrieval Room at FACT, in a way to bring the viewer along my journey, along a loose narrative path. At Tate you enter a controlled space, like that of the secret CCTV station, and at FACT you ‘remember’ the experience through retrieved footage and my letters.

The viewer approaches the work as a ‘third party witness’: He or she watches me being watched. I imagine some viewers identify with the controller and some identify with me. I am an individual of the public under view, one who has been singled out. Some people find this position scary and others find it desirable. I found it to be the latter.

GL: Late 2002, during the WorldInformation.org festival in Amsterdam you have already done a work that involved police security cameras. Was it really different to work with the Amsterdam police department?

JM: It was very different, but this difference reflects my approach. With System Azure, I transformed myself from an artist to a businessperson in order to be seen by the police. My intention, in either case, remained the same; this transformation was necessary for them to hear me. I was curious to explore how those in authority related to their cameras- as ornaments or as serious tools of security. Once we established the cameras ability to act as architectural ornament for the police building, the negotiating space and the project itself became more theatrical. The deeper we got into the patterns and colors of the fake jewels, the farther we moved from the camera’s so-called intended function. It was this slippage that intrigued me; I questioned the representation of power verses the activity of power.

Working with the Liverpool police was more collaborative. I did not clearly state my position in terms of career, rather my interest in using the system. The work was not about representation, but about function. I wanted to expand the function of the system- a function that was latent within it- and I needed them to work with me.

GL: In Amsterdam your artistic strategy consisted of the ‘beautification’ of public security cameras: ornamentation of something that is essentially ugly and suspect. Did you try to make the cameras visible? Was the idea as simple as that? I found it interesting that you did this in the red light district.

JM: While the final product-the jeweled camera- is simple, the story behind it is layered. This is true for a surveillance camera even before it is ornamented. Surveillance cameras are painted beige as to not stand out too much, yet- as with the police cameras I used, they are often large and prominently placed. The police themselves, remarking on the tools’ inherent contradiction, explained how the perception of the cameras depended on who was looking: invisible to the innocent civilian yet a deterrent to the criminal. To be hidden and to simultaneously act as a signifier is quite an ambiguous position!

Attached to the police headquarters the cameras announce their power: the power to look down on those walking by, from nine different positions. In this way the camera is both an ornament and a tool of power. A security camera on a police station is like a gargoyle on a castle.

It was the police that offered the colors, and the meaning attached to them. According to the authorities, the color red, meaning liefdevol or ‘full of love’, represents ‘police love’. What is that and what does it mean? Love for whom and in what form? My proposal to ornament police cameras in the red light district in red jewels simply put that question out there. In this area of Amsterdam, red is the sign for prostitution; the color signifies the place of consumption and the kind of services rendered. To use red on the police cameras adds this meaning of the color with that of the police. What happens to their meaning then? Asking the police to cover their cameras in red jewels (and red hearts) is also a way of asking them to claim responsibility for their cameras (as opposed to the shops and pimps that leave them beige).

GL: You mentioned that there are those who are exhibitionists, and those who are not.

JM: Some viewers who saw my work reacted to me in a kind of horrified way, saying how scary they found my ‘watched’ position to be. Others told me they wished it had been them. One man said to me that he wanted to be ‘the girl in the red coat on the back of the motorcycle’, in reference to my video entitled Final Tour. I have also been told that there seems to be a large group of young women who are drawn to the work as a kind of escapist fantasy. I did experience this to be true when I returned for our talk at FACT. I am not surprised by the two opposing reactions, as many of my projects in which I have placed myself before the camera have elicited similar contradictory responses.

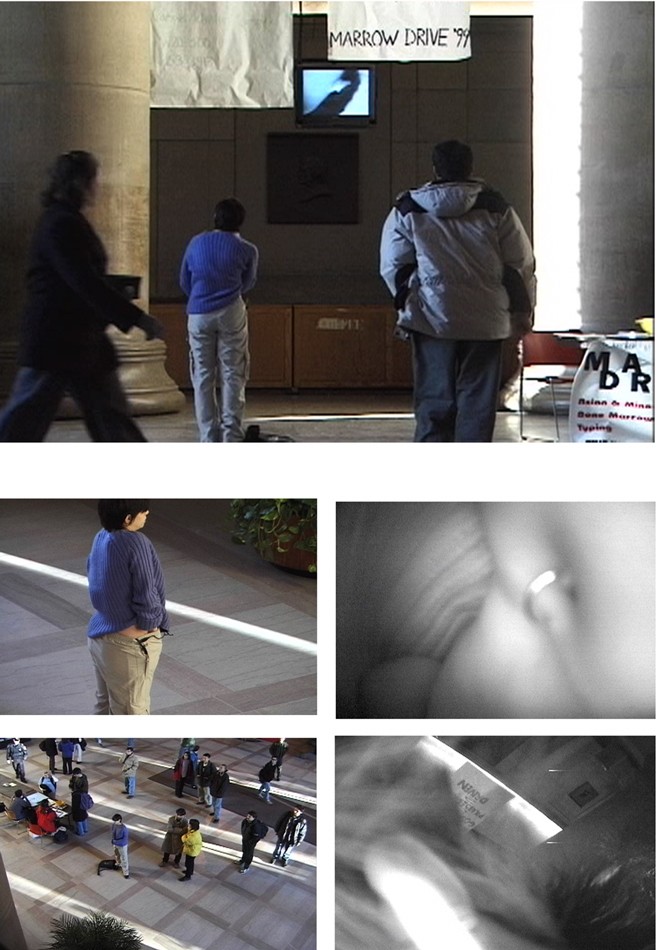

I did a project at MIT called Lobby 7 in which I hijacked the lobby’s informational monitor to broadcast my own transmission. This transmission was a real time exploration of my body beneath my clothes via a pinhole surveillance camera that I held in my hand. While the experience of exposing myself in this lobby was terrifying, it was also exhilarating. I created a new relationship with my body, as well as to the lobby and the people in it, via this technology. It left me stronger and yet more vulnerable. I don’t assume that everyone wants to feel this, or would feel this way from the same performance. We all choose the kind of relationships we like, and the roles we like to play.

GL: How would you describe the audience responses to the piece? It certainly raises a lot of questions, in particular about your role as a performer and artist.

JM: During the performance I was not aware of the audience response; I did not take my eyes from the monitor. I watched myself while the audience appeared and aggregated in the lobby behind me. You might call them witnesses. I could hear comments of those people who watched closely behind me, and others as they passed.

I could hear one couple close by for at least half the piece; they discussed the composition of my body on the monitor and how my skin related to the surrounding architecture. Two men, looking like professors, passed and one asked the other “what is on the monitor?” his response: “I think its one of those videos about a baby being born.” I was told seven police officers came in and asked people who put the sex tape in the system. These reactions say a lot about how images of the (female) body, in general as well as in the academic environment of MIT, can be perceived, as well as the assumptions that come with those perceptions.

In the days after the performance, at least five women came to me and said she wished it had been her. Other women I did not recognize gave me nods, smiles, or angry looks around campus. Both men and women seemed to look at me longer.

In the documentation video (I had people hiding in the above balconies filming) it was clear that the image was not readily legible; the viewer would look at the monitor confused and then his/her face would betray recognition. Some looked around to find who was doing this, but many just stared at the screen. Viewers often changed the way they stood: pulling baseball caps lower, or crossing their arms before their chests. Others put their hands in their pockets.

The best reaction I got was from a professor of mine named Ed Levine. He told me that after he had seen the performance, he could never look at the Lobby 7 monitor again without seeing the image of my body on the screen.

Lobby 7

GL: At MIT you studied with Krzysztof Wodiczko. Is it through him that got involved in this type of performance?

JM: Not directly. Krzysztof was part of a team of professors, amongst which was Dennis Adams, Julia Escher, Ed Levine, and later Joan Jonas. I chose to go to MIT because I had no longer been satisfied with my studio-based work. I lived in New York and felt a need to engage with the city directly. I was making models of architecture that I wanted to build within the city, which would exist as pockets of silent or intimate space. The professors asked me if I had experienced these spaces I imagined, and suggested that until I was offered the millions of dollars it would take to build them, I should find a way to test my designs. I scaled the models down to wearable objects and clothing. The only way to test them was to use them, out in the urban environment. I guess you could call this the beginning of my performances.

GL: Out of the rich Liverpool material you have been trying to extract a film script. Are you really thinking about feature film? Would you use the original footage from the security cameras? Would it be fiction or something in-between, like a hyper real fictionalized documentary?

JM: The original idea was to use the police footage I have and to adapt the Subject Access Request forms (the letters) I wrote into a script. I hoped to make it a feature length film with a narrative structure closer to fiction than documentary. Since the beginning of the project I wanted to treat the system as a film crew making cinema. Beginning this process of adapting the footage into a feature in LA this summer taught me a lot; the approach I used to make the videos for the art installation did not easily translate to a cinema space, and I am still considering how this can be done. There is surely a Hollywood story here; the question is how to do it. I am also curious to see if someone within the film industry takes this challenge on. I love the idea of police surveillance footage inspiring a Hollywood film- of the project making a full circle. I surprisingly found that what I was faced with- adapting the footage for a feature- was closer to the process reality TV editors face rather that of film directors.

GL: What’s the purpose for you of making narratives? This seems to be an important drive of you in your artworks.

JM: I don’t often feel in control of the narratives that happen in my work. When a narrative does happen, I am usually riding along with it, to a place I am unsure of until I am there. I also would not say that narrative is consistent within my work. The work I do with mirrors is more of an action. With the mirror tools and videos, I cut small mirrors to fit the shape of my hand or to fit the object I want to catch or hold within them. For example, if I want to hold a skyscraper, I cut a small mirror the size of a pen. In it, I catch the Empire State Building. Through the video lens, I drag it across the skyline.

The narrative of Evidence Locker grew from a process, or a series of actions. My intention upon arriving to Liverpool was to use the CCTV system as a film crew, to act as the protagonist, and to be saved to the evidence locker forever-or at least seven years. I planned to use the Subject Access Request Forms as my diary in the city. I don’t think most of us imagine our diaries as a story, but of course it reads as a kind of narrative. The (love) story grew from out from the relationship that the controllers and I formed through the camera, especially with one of them.

As for the general occurrence of narrative, I would refer again to my desire to bring abstract concepts closer to me. A way to do this is to re-write or reconstruct myself into them. This process is a kind of storytelling to myself. It is this story I present.

GL: Could you tell us more about the difference you make between private and public spaces?

JM: To describe private space, I often speak of bubbles. Inside the bubble is private, outside is public. The boundaries are subtle, possibly invisible. The inside is softer, quieter, and time runs more slowly. Like Foucault’s notion of heterotopias, this bubble is a mirror of its surroundings. In the mirror I see where I am not. A bubble can appear inside of other spaces, while everything outside its boundaries continues on as it was. In my example above, I use a small mirror to hold the Empire State Building in my hand. For me, I have used the mirror to create a bubble for the tower and myself. Inside I can hold it.

GL: What is self-surveillance in your opinion? Is it self-examination or rather an urge to control your own image and reach a stage of super self-awareness? Do you think that the presence of so many cameras means that we are ‘internalizing’ technology? Is it really ‘invading’ our bodies and minds or do see ways to ignore it?

JM: Self-surveillance is a way of seeing myself, via technology, in a way I could not otherwise. In self-surveillance I use a system or a technology as my mirror. The type of reflection I face is specific to the tool I am using. Who I appear to be in that reflection is unfamiliar. The process of coming to recognize myself as I appear there is what I call my work.

—

URL of the Liverpool Biennial project: www.evidencelocker.net

Security Ornamentation website: www.systemazure.com