In that paradoxical state of distraction and boredom typical for later afternoon browsing, whose secret key only data miners possess, I stumbled upon some fascinating images on Boredpanda.com (81K views, see below). These images were posted by Paulina Tikunova, author of “Cute Self-Watering Animal Planters”, “Woman Takes Engagement Photos With A Pizza To Show It’s More Reliable Than A Man” and “10+ Funny Animal Puns To Make Your Monday Pun Again”. (I imagine working at Boredpanda.com to be quite demanding). Intrigued by the images, while also already slightly troubled over what I suspected was their “critical message”, I spun the wheels of mighty Google, finding that the following images are part of an art project called SURF-FAKE by young artist Antoine Geiger, and part of the larger project SUR-FACE.

Silence in a world polluted by surfaces

To my convenience, the project website contains a pdf document that succinctly explains the artists’ take on the matter. It begins with an autobiographical confession of a life-long interest in “images of anonymity” and their popularity in art, pop culture as well as fashion, e.g. Maison Martin Margiela‘s models. Luckily, Geiger is not alone in his fascination. Bogomir Doringer’s Faceless exhibition completely revolves around a surging interest in anonymity in the creative industries, on which more here.

Conceptually, Geiger locates a ‘crisis of identity in our contemporary world’, which is due to an over-exposure of identity inherent to a ‘cult of the self’. In terms of power, this means that ‘People are now ruled by marketing’ as ‘everything is traced, rated, shared, followed’. Together, this results in increased vulnerability and loss of control over our personal lives. Incipit tragoedia: it seems that the attempt to assert ourselves socially and in publicly leads to an even more unbridgeable alienation and loss of self: ‘the whole world has become a world of surface, of imitation, and a constant overlaying of short trends’. Yet this world of surfaces is far from transparent: the surfaces cover each other in an never-ending whirlwind of commodified copies of copies without origin.

In response to the conundrum of our manipulated, mediatized mirror palace, Geiger offers “silence” as ‘the solution that always linked humanity’, using the commemorative “minute of silence” as an example.

This brings us to what I consider the more dubious aspect of Geiger’s SUR-FAKE and SUF-FACE project. For reading said document left me with a sense of “Here we go again”: yet another neo-romanticist reflex to contemporary media culture that opposes a more attentive and sensible “silence” to the cacophony of modern existence.

At this point in the document, the whole discourse shifts into esoteric gear. Silence, as a precarious remnant of, and as a shelter to, the nihilistic un- and infolding of media surfaces, as that which reveals itself in between, is said to mark an inner beauty and underlying unity, offering ‘a way of protecting one’s deepest state of sensibility’. The respect, care and overall ‘feeling of comfort’ that this silence affords is said to be the ideal to which we all tend, ‘in the end’. Silence is the alternative to a ‘virtual world of illusions materialized through images overlaying each other, hiding authenticity and truth’. Silence as beauty is that what, together with happiness, escapes us, but which we nevertheless continuously seek. The beauty of silence guides us towards ‘the invisible, the unspeakable, the unreachable […] a kind of internal and eternal feeling of joy and transcendence’.

This art turned social critique is reminiscent of the great ascetic-iconoclast attacks on popular theatrical spectacles, but – how strange and paradoxical! – one grounded in a post-structuralist emphasis on the body and its rhythmic expressivity in dance, rather than on an Augustinian solitude of mind in its infinite conversation with the supreme Spirit. Does not the body here simply function as the Spirit’s contemporary equivalent, the new fetish of a postmodern religion before which postmodern art-magicians kneel down and pray, their Deleuze and Derrida pocket editions in hand?

The apparent impossibility of opposing a curiously ascetic aesthetic of the pleasurable body commuting with others through the impersonal medium of gesture (rather the vertical integration of a solitary mind in a communion with the divine) to the equally sensuous injunction of a capitalist consumer society – I propose to call a humanitarianism or a “humanism of the body”. The latter terminology captures the paradoxical character quite well if you consider the principles of classical humanism, for which the body remains associated with an animality that prevents us from achieving true humanity, the body being the common denominator of human and non-human life as mere zoë, bare life.

Interestingly, this ominous reversal in the perspective of social critique from that of an inner spiritual superiority in early Christianity, to a radicalized Deleuzianism or communism of the body, proceeds via a critique of the consumerist everyday as itself ascetic, “in the last instance” (at least this is what its main theoretical protagonist, Herbert Marcuse, argues). Did all worldly affairs still unambiguously represent – for Christian ascetics – the chaos of the sinful flesh, now these same affairs are criticized for being asceticized and domesticated restraints on everything the body is capable of: the specter of a protestant ethic still looms large on the horizon of the endless potentiality for the pleasures of the flesh – a very curious reversal of Christian eschatology.

But at this point we have far outreached the starting point: Geiger’s emphasis on a bodily ascetics of silence fails to push these contradictions to their outer limits, at which they are forced to revaluate themselves. Deleuze’s true accelerationist thoughts approach this threshold, but ultimately refrain from entering due to the uncanny resemblance to the cultural logic of late capitalism, finally defaulting, in What is Philosophy? , to a melancholic anti-capitalism.

Of mannequins and pets: our digibestial imaginary

In a treatise on how young children acquire a sense of self and others, the French phenomenologist Merleau-Ponty resorts to the figure of the mannequin to visualize one core aspect of our relations to ourselves and others: I notice that ‘I have a body which can be seen from outside and that for others I am nothing but a mannequin, gesticulating at a point in space’ (The Primacy of Perception: 120). Yet in order to fully understand others as distinct selves I need to acknowledge that these mannequin-like gestural beings are actually animated by a psyche, like I am.

The face is the primal scene of recognition for children and adults alike – it is also seen as the sign of our humanity (do animals have faces?). With the life-like wax statues exhibited in Madame Tussauds around the world, we nevertheless feel something is missing, and this “something” would then be phenomenologically equivalent to what Mzerleau-Ponty designates with “psyche”.

In Ex Machina (2015), a film about the question whether an A.I. robot (called Ava) can be said to possess genuine personhood, her face is made to look naturally human, while in the stomach area the underlying machine-design is laid bare, which, contrary to the face, in the case of human intestines severely disturbs and disgusts us. Instead, with the face it is precisely its veiling that disturbs us. Thus, there exists a kind of inverse relation between face and belly. This corroborates the Western cultural symbolism of the belly and the face as mutually exclusive aspects of our two-tiered being, marks of our bestiality and humanity, respectively – an archaic prejudice that curiously survived the purge of ratio-scientific reason. Compare Ava to the masked Marginal model below, whose fleshy belly instead clearly shows, emphasizing sensuality over personality, the impersonality of the flesh over the singularity the human face.

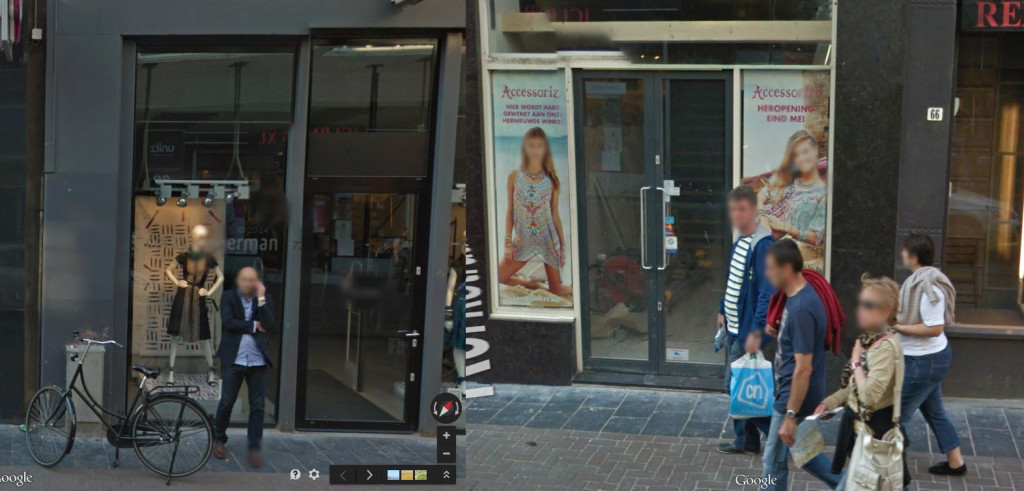

Merleau-Ponty’s reference to mannequins reminded me of Google Street View, whose facial recognition software sometimes accidentally detects and blurs the faces of mannequins on display in shop windows. In the name of the urban dweller’s illusory sense of privacy, Google’s algorithm, by recognising shop front mannequins as human persons, conversely can be said to capture and interpellate us (“real” human persons) as mannequin-like entities, puppet faces hanging mid-digital air in our everyday strolling past shop displays, reminiscent of Morandi and De Chirico’s manichinos (mannequins), as well as George Grosz’s “Republican Automatons”.

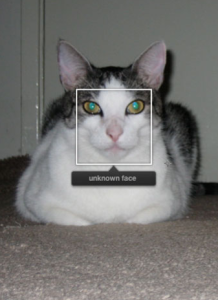

Besides mannequins, facial recognition software may also welcome animals amongst its false positives. By traversing the conventional boundaries between human and animal, in the indiscriminate capture of biological elements that they have in common, such algorithms points to a fundamental “openness to animality” of biopolitical technologies in general. Hence, techniques used for totalitarian forms of surveillance and biopolitical control also bear witness to a shift in forms of experience and understanding that bring about, often despite themselves, a surreptitious “redistribution of the sensible” increasingly agnostic to anthropocentric distinctions between human and animal, organic and non-organic, natural and artificial, etc.

The hermeneutics of the face shifts between a natural and a super-natural reading: on the one hand, Darwin’s contention (in The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, 1872) that the play of facial features can be subsumed under a physiognomy of transspecies sign-play, understood as a function of evolutionary dynamics; on the other hand, an accountancy of the face as bearing witness to our divine likeness, ‘being made in God’s own image’ that marks the face as the site of exclusively human belonging.

Fake faces

Among the questions that Geiger asks, ‘Can we find identity beyond the face?’ appears to me the most interesting and politically pertinent. It is related to a question posed elsewhere: ‘What if we erase this focus on the personality, the individual?’ The mask, insofar as it hides or obscures the face, abstracts from people, and produces a ‘visual silence’ that shifts the focus towards ‘the expressivity of the body’, whose gestural medium is that of dance. So far so good. But this dance might not be one of attentive solitary care for an ungraspable inner beyond (impersonal as it is), but rather a collective and above all cruel immersion in the whirlwind of floating other-images. In this case, the transmogrified multitudes pass Maxwell’s demon as happy militants of an emerging digibestial imaginary, so that the return of the mask will genuinely be, as Foucault suggests, ‘the explosion of man’s face in laughter’. In this respect, we may have a lot to learn from popular web culture. lol.