The day comes to an end. Tired of abiding to the rules of productivity you sit back, relax and prepare yourself for some hours of dolce fare niente on your social network of choice – you log into Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and are now ready to catch up with your friends, acquaintances, family et al. An advertisement for something vaguely familiar steals your attention. And then another one. You install AdBlock but still are bombarded with friendly requests to vote on some contest which requires you to like some company's page in order to proceed, or with delicious instafood from the fast food chain down your street. Oh wait, what is this? ‘23 surprising ways M&M's make your sex life better’? What fresh hell is this? Why do you find yourself unable to relax, exhausted from all the stimulus, feeling pushed from one hyperlink to the other as if a sudden gush of digital wind unearthed you from the comfort of your sofa?

Labor Organisation in the Digital Space

Welcome back to working hours - or at least that is what Dallas Smythe, a political activist from the 1970's would say. According to Smythe's 1977 essay 'Communication: Blindspot of Western Marxism' our services, as audiences, are sold by mass media of communications to advertisement companies. We are fed for slaughter, that is to say, manufactured and produced by these corporate social networking platforms such as Facebook and Twitter in the present case, so that our increasingly predictable behavior can generate ever more targeted ads. What this means, in practical terms, is that all the content you are being subjected to has been parsed by an algorithm which determines what reaches you and what doesn't. This is done either by means of algorithm learning – e.g. if you comment on a friend's status you are more likely to have her pop up on your news feed in the future - but also through more invasive, rather unsavory tactics, which we will explore further later on.

The novelty introduced by these corporate media monopolies is precisely the extent to which they govern their employees', excuse me, users', behavior. ‘Society cares for the individual only so far as he is profitable’ said Simone de Beauvoir, and likewise corporate social networks only care to offer us a free service as long as we are deemed profitable.

Facebook's Statement of Rights and Responsibilities, Data Policy and Principles

However, this conversation makes little or no sense disconnected from its historical context and the opposing, though complementary narratives of state governance, market economics and media activism which assisted the birth and growth of these technologies: as we shall see, these dialectical forces midwifed the business model of corporate social networks.

Once Upon a Time... The Internet

The precursor of the internet, ARPANET, was a network architecture devised by the U.S. Defense Department Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) as a response to the Cold War. In the event of takeover, American communications would be secured since the whole of the network could not be controlled from any central point. Such architecture was constituted by a vast amount of computer networks linking to each other in numerous ways. Funding of the research leading up to this project was secured by the Information Processing Techniques Office (IPTO), which is also part of DARPA.

American universities have also played an important role in the development of networking technologies: as described by Katie Hafner and Matthew Lyon in Where Wizards Stay Up Late, networking infrastructures were installed in universities per request of IPTO contractors, who were there conducting their research and in need of more advanced computer resources.

In an attempt to cut back costs, ARPA built a system of links between machines, which allowed for resources to be shared more effectively. That way, everyone could virtually access the most advanced machines without them having to be physically present. As stated by Hafner and Lyon, with the growth in number of computer science departments, however, universities with no access to the Net started to fall behind. The ability of colleges to host an ARPANET node was determined by their involvement in government funded research on military related areas, not to mention the high costs associated with the allocation of new sites. Eventually, Larry Landweber from the University of Wisconsin proposed the establishment of CSNET (Computer Science Research Network). After some defining meetings and proposals, CSNET was established as a three-layered structure involving (but not funded by) ARPANET, a TELENET-type system and the PHONENET e-mail service. By 1986, most American computer science departments were already connected.

Parallel to its military funded and scientific research origins, several other, more disruptive projects emerged that contributed to shape contemporary internet. Their mention is of key importance if we are to discern the often contradictory, but intertwining exchanges occurring at the level of networked communications and which constitute the core of digital economy.

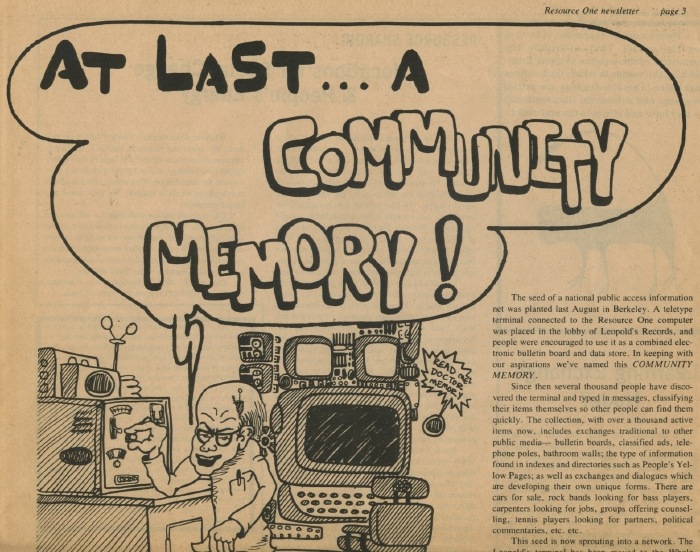

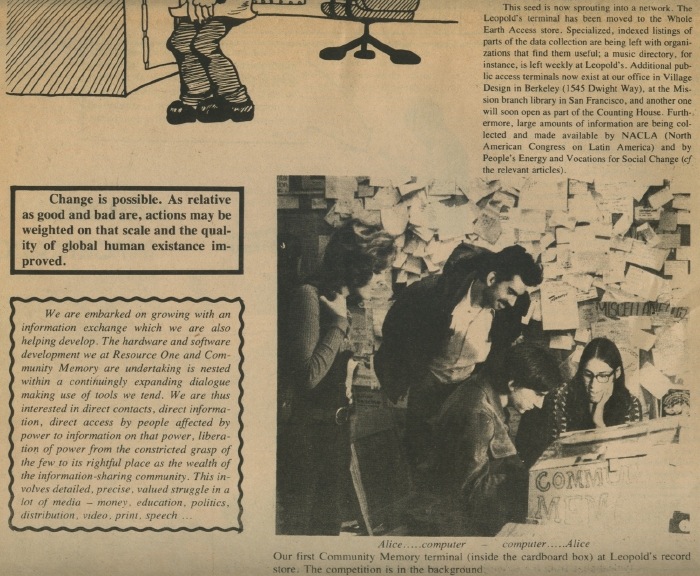

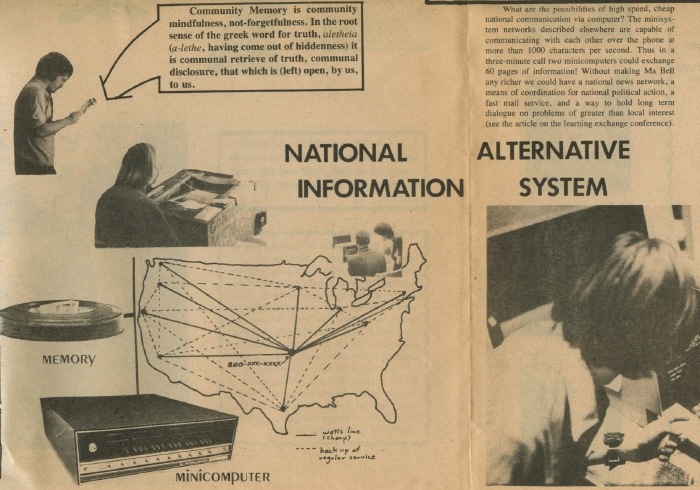

Another side of the story is Community Memory, a 1973 project by Efrem Lipkin, Mark Szpakowski and Lee Felsenstein. This was the precursor to many computerized bulletin board systems (BBS). Its terminal was placed, per permission of the student senate, on a record store in San Francisco, which had been set up by student government to drive LP prices down. Users of Community Memory could easily add or search for messages using a terminal program. What started out as ‘an attempt to harness the power of the computer in the service of the community’, ended up by opening doors to various degrees of exchange, from art, literature, education, journalism, etc., actively shaping the social and economic aspects of the community.

Networks such as BITNET (Because It’s Time Network) and USENET are also worth mentioning as examples of decentralized, distributed structures that pioneered the contemporary web forum. Implemented in 1981 by Ira Fuchs, BITNET was a college computer network functioning between university institutions. The transferring of files occurred from one server to the next until finally reaching their destination. Its distributed network structure resembles that of USENET, founded in 1980 by Tom Truscott and Jim Ellis, a discussion system still operational nowadays. Users post their messages on newsrooms. These then circulate from one server, which might be hosted by the user themselves, to the other.

Both streams were instrumental to the development of the internet as we know it, and I argue that corporate social networks have managed to utilize the desire for community based projects and decentralization in the creation of a very successful business model.

The commercialization of the Net is not a new tendency – according to Richard Barbrook's and Andy Cameron's The Californian Ideology, ever since these technologies became popular market libertarians have been advocating for their profitable benefits. The decentralized structure of the internet was understood as a means of escaping the control of state-regulated economies and everyone with access to the internet was a possible entrepreneur sailing the vast free market sea.

Mirko Tobias Schäfer further explores the idea of self-organized communities in his book Bastard Culture!. Schäfer examines our interaction with culture in a variety of ways, questioning the extent to which we participate in it and how. The author identifies participatory culture with the fading barriers between amateurs and professionals, users and producers. Technology both enables and shapes participatory culture: users actively act upon, construct and modify cultural content in the digital space through the use of wikis, blogs, forums, etc.

New terms have been coined to describe this user-generated culture: producer, prosumer, DIY culture, peer-to-peer etc. Ideas of collective and communitarian collaboration come often associated with it. However, Schäfer recognizes participation is not always explicit. Explicit participation relies on the appropriation of technology by users and further development of their technical skills. Examples of explicit participation can be found in slash fan-fiction websites, software collaboration platforms such as github.com, Wikipedia and all manner of wikis, blogs, social networks, etc. Another layer Schäfer recognizes is implicit participation. This is a consequence of design choices that take advantage of user activity and habits. These are platforms which benefit from user generated content contributing to information management systems, which can be exploited for improving information retrieval or gathering user info for market research. Adding tags, clicking 'Like' buttons or placing 'Like' buttons on a website are examples of such level of participation. It becomes thus difficult to access the extent to which our participation affects cultural production.

It is within the context of participatory culture that corporate social networking labor on platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Tumblr emerges. These entrepreneurial ventures, as Schäfer puts it, have realized social network users’ importance in the consumption and distribution of commercial messages. The advent of networking technologies, with its accompanying promises of decentralization and freedom, bore with it a poisoned gift: born and developed within a capitalist framework, mainstream networks opened up new dimensions of the subject for surplus extraction ventures, as well as more possibilities for mass surveillance.

But let us get back to how labor occurs in corporate social networks by taking this analogy with work even further, picking apart the pieces which keep the digital factory up and running and drawing a comparison between them and traditional workplace artifacts such as employment contracts, curriculum vitaes, etc.

THE SOCIAL WORKPLACE

Terms of Service

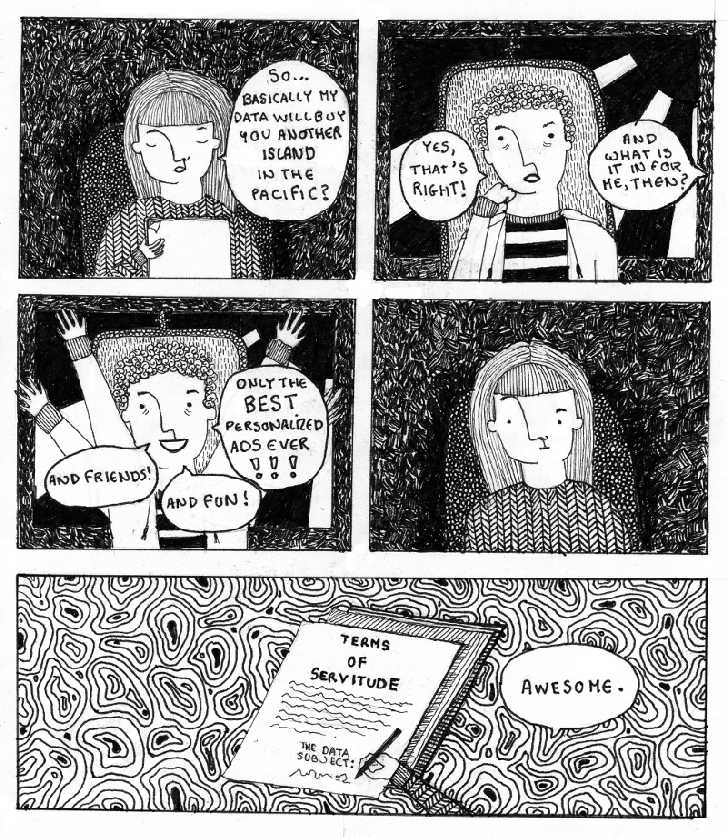

Regulating the data exchange between users and the platform we find terms of service, data policies, statements of rights and responsibilities, etc. By any other name, these documents can be conceived as the data labor iteration of an employment contract.

For example, as Facebook employees we are to keep our contact information accurate and up to date, impeccably curated so we don't provide any false personal information. This, of course, serves the purpose of accountability, market-polished data which is sold to advertisement agencies, guaranteeing our job is done with aplomb – the more accountable we are, the more profits we derive for our employee. This means we are also to agree with the use of our name, profile picture or other personal information in connection with commercial or sponsored content. Additionally, if we hail from somewhere other than the United States, we consent to having our personal data transferred to and processed there.

While it is true that we only accept such outrageous conditions that deeply violate the most basic human rights if we choose to sign into these platforms, the only other option we are left with is opting out. And whilst the latter is certainly a viable option, in most cases the 'network effect' grabs hold of our agency and ensures that it is not the most feasible option for the vast majority. The 'network effect' is present whenever a service is the more valuable the more users it has: ‘If I delete my account, I will lose contact with my friends’, ‘I tried to get out, but I started missing a hell lot of events because of my decision’ are just some of the consequences of leaving. Increasingly becoming the center of our social and even work lives (e.g.: LinkedIn, Facebook at Work), it certainly becomes difficult to step out of the information loop.

Overall, Facebook's Terms of Service interface presents a high level of hyperlink mediation, and thus the whole experience is designed as an obstacle race that only the most resilient users will complete with success.

Facebook's Statement of Rights and Responsibilities, Data Policy and Principles

Being strategically far from unequivocal and explicit, Facebook's Terms of Service fuzziness plays to the platform's advantage, as one would expect it to. Its ambiguity leaves plenty of space for both confusion on the employees' side, and creative interpretation from the employers' perspective. Their own little social experiments are usually conducted on the grey areas of such terms. For example, in 2014 major outrage broke from the scientific community at the news of a study, conducted in 2012, by Facebook researchers. The study consisted in filtering out approximately 700. 000 users' news feeds by means of two tests. One test reduced the positive content on users' news feed, whilst the other reduced negative content. Not having asked any permission to the community, such study constituted a violation of the principle of “informed consent” and actively tinkered with users' emotional health, leading to changes in behavior. This latter is nudged and guided through page, friends and group suggestions, under constant scrutiny for more accurate market profiling.

Another interesting example relevant to this argument was exposed by a Slate article back in 2013, and it refers to a study conducted by Facebook waged employees regarding self-censorship. Self-censorship refers to those status updates we later chose not to post – be it because we are not fully convinced everyone is interested in our pile of dirty dishes, or because we don't want half of our 'friends' calling us out in anger for expressing our opinions on yet another uninformed and superficial hashtag activism campaign. Jennifer Golbeck, the writer of the article, reached out to a Facebook representative regarding her doubts on whether this prying was foreseen by the terms of service. The answer that she got was highly predictable – ‘a representative told me that the company believes this self-censorship is a type of interaction covered by the policy’. But should these terms really be left up to interpretation?

Advertisement

In March 2015, an article on the Technology section of The Guardian reported Facebook’s misuse of user and non-user data, actively breaching EU law

A report, commissioned by the Belgian data protection agency and conducted by researchers of the Centre of Interdisciplinary Law and ICT, the University of Leuven and Vrije Universiteit Brussels, had been published recently. It denounced the company's abusive practices in regards to the tracking of user data for targeted advertising purposes. These practices extend beyond the platform itself and apply to any website making use of Facebook’s services such as Share and Like buttons. These buttons place cookies on the users' browser which then retrieve their online behavior information. There are options offered for opting-out of advertisement on diverse online platforms, Facebook included. However, as the report shows, for EU citizens that just means the placing of a new cookie on the user’s browser.

Christian Fuchs and Sebastian Sevignani pick up on Dallas Smythe’s equation of advertisement consumption with work to argue that profits, on corporate social networking platforms, are extracted from the commercialization of user data for targeted advertising purposes. According to the authors, information work is three-fold and involves cognition, communication and co-operation. Their defense of labeling these activities as work is based on Marx’s argument which equates them with the existence of labor power’s action on objects and instruments for the creation of products with a use value. For example, on corporate social networks, communicative digital work’s objects are human experiences and online information. Some of its instruments are the brain, the hands, the social media platform itself and speech, and the use value created are the 'new meanings established in social relationships'. The authors distinguish between work and labor, in the sense that labor is alienated work in a class society that creates exchange value. Corporate social networks encompass both work and labor: according to Fuchs and Sevignani, the products created by users don't only satisfy their needs, but also the platforms' drive for profit.

In practical terms, it means that Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and such derive their profits from selling your interests in movies, music, books, companies and people to advertisement agencies which then are able to better ‘serve’ you. Are you a huge fan of Anton Tchekov? Maybe you would like to buy this new, revamped luxury edition. Oh, you have AdBlock installed? Don't worry, there's other ways to advertise. Why not like the official page of Barnes and Noble?

Whilst this might be old news, it is generally framed in public discourse and mainstream media as an attack on privacy. However, another thread of this discussion that is increasingly gaining some traction is that which applies the lens of labor theory to our activity on social corporate networking platforms. That is certainly the motivation behind ‘Digital Labor: The Internet as Playground and Factory’,which characterizes this phenomenon as playbor. Andrew Ross's contribution ‘In Search of the Lost Paycheck’ is one such example where the author starts by questioning whether we should be classifying our social network activity as labor, only to conclude that even Marx predicted:

‘the increasing dependence of capitalism on the 'general intellect' or 'social brain' – the vast network of cooperative knowledge that is the source and agent of the cognitive mode of production.’

Besides, argues Ross, waged labor is not the only way work is performed under a capitalist system.

Social Graph

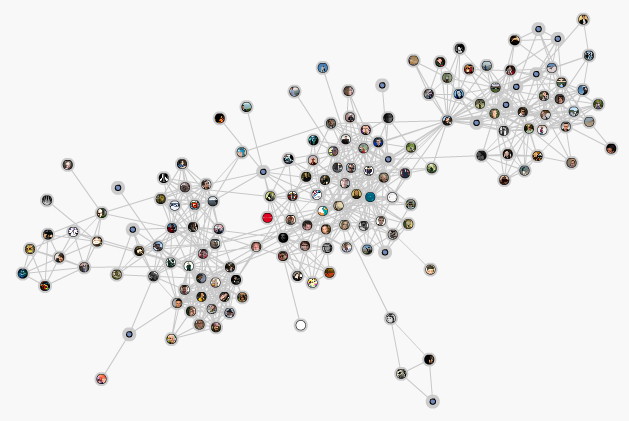

Initially introduced during the Facebook F8 conference in 2007 within the context of the Facebook Platform, the Social Graph has now expanded to become an attempt at the graphical representation of relationships between everybody and everything on the internet. This representation is done in terms of nodes (users, pages, etc) and links (relationships) between them. In 2010, just three years after its introduction, the Social Graph became the largest social network dataset in the world.

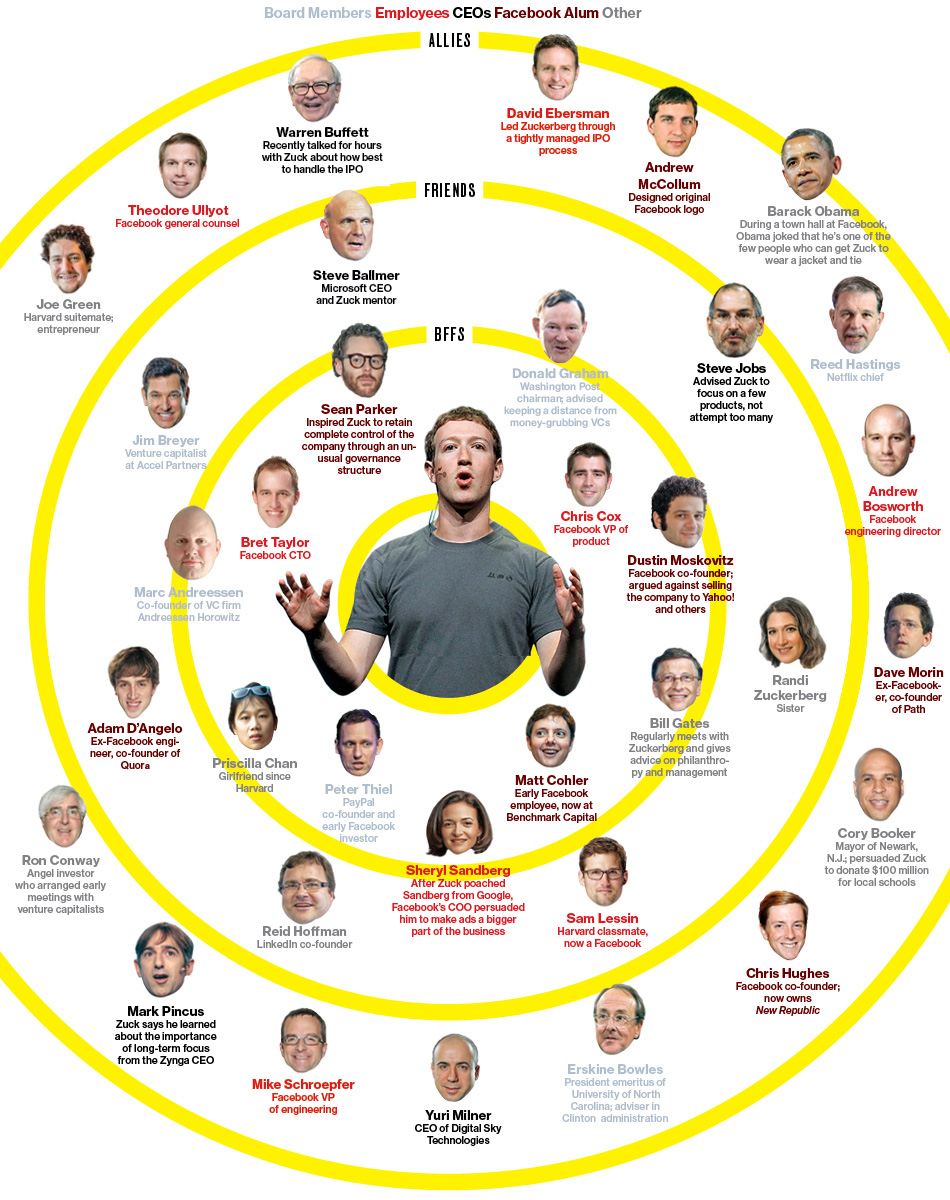

For the sake of clarity, we will attribute the Social Graph the role of the manager, whose function is to organize its employees in the most thriving, efficient arrangement possible. According to Alexander Galloway, the protocol allows for such management. Within this context of a decentralized network, the protocol secures its control. Computer protocols define the standards through which technology is implemented, regulating the way according to each different technologies communicate between each other and, ultimately, how users interact with it. The Open Graph protocol, which facilitates the integration of other pages within the social graph, authorizes web developers to embed their pages where they acquire the same functionality as other graph objects. What this means is that it becomes possible to access not only people and their interpersonal relationships, but also liked pages, events, photos and the links between all of these.

Your position in the graph largely determines which content is displayed to you, so whichever friends you interact with the most on the platform, will be the ones' whose content will be more likely to show on your feed. Eli Pariser warns against the perils of the ‘filter bubble effect’. This explains the phenomenon through which our knowledge is funneled down to what we already know – the algorithm feeds us information related to our previous preferences. By narrowing down our choice of behaviors, the risk of unprofitable idiosyncrasy and noisy unpredictability is highly diminished.

This structure would be better analyzed within the context of social engineering. The mainstream definition of social engineering characterizes it as a discipline in social science regarding the efforts undertaken by governments, media or other private groups to influence popular opinion and attitudes. What this means is that social engineering is a powerful apparatus for enforcing ideology, guaranteeing the elite’s dominance over the functioning of the whole economical system. Simply put, social engineering is an instrument at the service of economical reproduction.

Illustrating this particular point, is yet another delightful Facebook study conducted weeks before the US elections in 2012. 1.9 million Facebook users saw the number of hard news stories increase on their news feed, which resulted in an increase in civic engagement and voter turnout.

This ability of influencing people's behavior is very preoccupying, especially once we become aware that, within these platforms, everything serves a sole purpose: productivity. Sociologist Nikolas Rose thus sees confirmed his point according to which subjectivity has become a fundamental aspect of economical efficiency.

User Profile

A user profile might be the equivalent of the corporate social network to a curriculum vitae. It is our selling point, where we market ourselves to possible investors – be them investors of time, money or ill-advised intentions. Just like we are constrained to do with our CV's, there is pressure for our user profiles to be carefully managed, making us appear in the light we feel is most to our advantage.

Geert Lovink's ‘Anonimity and the Self’ underlines Israeli sociologist Eva Illouz position according to which professional and personal identities become confused within this context – we are nudged towards presenting ourselves as the best, fastest, leanest and happiest.

However, beware of the razzle-dazzle. Remember what we said on the terms of service section of this essay concerning these platforms' insistence on accurate, up-to-date profile information? The way to secure real-to-life user profiles starts within the rigid interface design that we wear as a uniform and extends up to the real names policy, guaranteeing as much as possible our accountability as employees. Zuckerberg states this clearly: ‘having two identities for yourself is an example of lack of integrity’.

LET US UNITE

If this is, indeed, work that we are committing willingly, though not always knowingly, to these corporate platforms, why are we not organizing and demanding better working conditions? Is it reasonable to expect labor struggles when workers exploitation is masked under rhetorics of sociality, connectivity and openness?

One strong argument against perceiving content generation for corporate social networks activities as work is that we don't feel corporate social networking's painful strain the way factory, office, public service and all other sorts of waged and non-waged workers do. We have fun; we connect with our friends in a joyful environment. Work is play/play is work, a logic that is spreading dangerously to other economic sectors allowing for the removal of more and more workers' rights. Aren't you happy doing your job? Then doing overtime shouldn't be a problem. But that's another part of this story.

Albeit all of these arguments being very true, it is not entirely accurate we don't feel our social network activity's noxious effects. The most obvious example might be the mental exhaustion provoked by the unending stream of information – like this page, check out how great your high school bully has been doing you lazy ass underachiever, please join this event, like my boyfriends' photography page!

But there are other, more pervasive and dangerous effects that most of us will probably never experience due to our relatively privileged existences. These can range from the real names policy, which has more than once discriminated against sexual and ethnic minorities, to authoritative states making use of facial recognition software to identify protesters in photos users post on these networks. The list goes depressingly on.

Another big stumbling block on the way to the political organization of labor within the space of the digital social is the general feeling of impotence – who to address, what to demand, how will it change?

Power is, they say, distributed. There's no hope beyond the blue horizon. Of course market independent alternatives exist, and one might argue that organizing corporate social network labor will only contribute to their exhaustion. By alleviating the work conditions of the mainstream social network users, are we not only manufacturing consent and accepting the view according to which our personal data should be mined for profit? For example, were we to be paid for our activity on corporate social networks, this would only reproduce a deeply flawed system instead of instigating the search for non-market alternatives.

That, I will admit, is indeed a risk. At the same time, it is quite utopian to expect the mass exodus from the lands of the blue Nihil into the promised land of the Commons. A project such as this would have to maintain a balance between providing better working conditions for the workers of the social factory whilst advocating and opening up the space for such alternatives.

Andrew Ross’s 'In Search of the Lost Paycheck' references the avant garde analysis which sees capital owners’ efforts to transfer work outside of factory walls as an attempt to get rid of unionized labor movements, which recent studies about the decreasing power of the union clearly show are a serious menace to the status quo. Florence Jaumotte’s and Carolina Osorio Buitron’s 'Power from the People' begins with the simple premise, which posits that the decline in unionization accentuated income discrepancies with an increased concentration of capital on the top incomes. Lower rates of unionization translate in a decrease of the workers negotiating powers when demanding better wage redistribution and so the available share for top incomes increases.

If we are to accept these conclusions, it becomes evident how lowering the power of the union and of the working class in general becomes extremely profitable for capital owners. Andrew Ross goes so far as to predict that waged labor will soon be perceived as a temporary chapter in working class history, and that for only a small minority, amidst unpaid domestic work and non-waged work in the informal sector, the latter which is expanding. Beyond factory walls, which nonetheless are still a reality for millions, we are the workers of the social factory, where value is extracted from our communicative, cognitive and co-operative work.

Ned Rossiter and Brett Neilson alert, however, to the dangers of subsuming all informational labor under an exploitative experience. In so doing, one fails to observe the potentialities for political organization emerging in these communities. It is precisely the examples of such potential which I will now be presenting to argue for the benefits of unionizing within the digital space.

International Data Union

The International Data Union was constituted as a means of addressing the treatment of personal data by profit-seeking corporations. They advocate for a data commons, wherein the rights over personal data remain with their creators. This would ideally be achieved through collective negotiation and action over the value of ‘this data for the benefit of its members’.

In their website, the International Data Union shares a list of user-friendly resources, composed of privacy, anti-surveillance, dark-web and data deletion toolkits, data visualization mechanisms and free and secure alternatives to commercial services. These resources comprise a range of browser plugins, such as Light-beam, which allows you to check who is tracking you online; a TOR bundle; practical steps on how to remove your data on diverse platforms; a data selling game and tools for creating believable fake identities.

Networked Labour

In the same line of cooperation with a network of related projects and community empowerment, we find the Networked Labour project. Networked Labour emerged from a seminar held by Networked Politics, transform!Europe, the Transnational Institute and IGOPNET in Amsterdam, in the year of 2013, with a vision to develop a web platform for a transnational, collaborative and decentralized network for collective learning on emancipatory labour practices. For the past two years, discussions regarding the restructuring of labor struggles under networked conditions have taken place in the Networked Labour mailing list, in the hopes of mobilizing “new contributors, observers and participants of recent social changes, innovations, movements, protests and mobilization”, as put by Örsan Senalp, facilitator of the project and mailing list administrator.

Recently, on May 2015, the project evolved into an online college, the Networked Labour University Proletkult 2.0, responding to the initial challenge it set following the Amsterdam seminar. The goals of such platform involve the creation of an open space for radical emancipatory projects to organize debate and learning circles, allowing them to cross-pollinate and foment collaboration between participants.

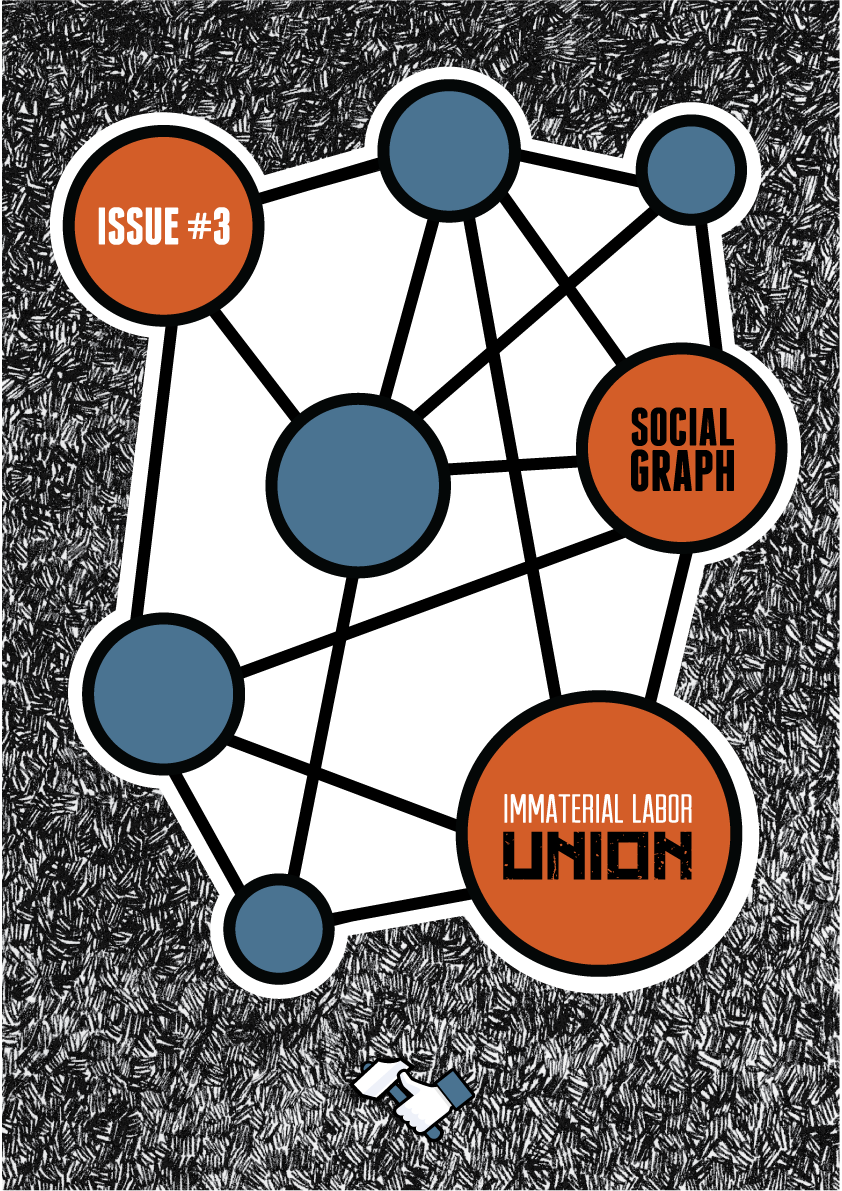

Immaterial Labour Union

For the duration of the past year, I've been experimenting with the creation of an Immaterial Labour Union, focused on politically organizing Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and other monopoly social network platforms' workers. The first step was the establishment of a publication in a zine format, wherein I invite contributors to present their thoughts on concrete issues such as the aforementioned Terms of Service, User Profile, Advertisement, etc. Contributions have ranged from academic text, to poetry, illustration, photography, digital collage and personal rant. Besides, the zine has provided a platform for the presentation and debate of concrete proposals.

Wages are an impossible topic to avert when speaking about a union. Inspired by the Wages for Housework campaign in the 70’s, Laurel Ptak started the project Facebook, when at the moment of rewriting the Wages Against Housework manifesto by Silvia Federici replacing the word housework with Facebook, she realized it was still shockingly actual. This project, whilst providing valuable points of disruption to the accepted discourse, exhausts itself politically when setting as its only goal the demand of wages, not questioning in depth a system that monetizes our intimate life.

In my opinion, a better approach would be the one proposed by Christian Fuchs in the second issue of the Immaterial Labour Union zine, which would see the implementation of an advertisement tax applied to the internet. Fuchs proposes then that the sum achieved would fund a participatory media fee, that is, with the revenues from the advertising tax distributed via participatory budgeting to every household there would be the obligation to donate to non-commercial media organizations for the development of alternatives. One such alternative was proposed by Marisol Sandoval in the following issue, in the form of a cooperative, open-source social networked going by the name of Commonicate. According to Sandoval, ‘creating prosumer co-ops could be a way to confront the problems of commercial 'social' media such as surveillance, free labor and corporate power’. Harry Halpin, however, in his contribution for the fifth issue demonstrated his skepticism of state handouts and reinforced the potential of bottom-up self-organization facilitated by these same networks.

There is still a long way to go and a great many debate to have regarding the demands of an immaterial labor union, but the discussion has already started and, seeking collaboration with like-minded projects such as the aforementioned Networked Labour and International Data Union, there is hope for the collective bargaining of our working rights.

A SPOONFUL OF VICTORY SUGAR

Examples of successful citizen initiatives are not hard to find. It was thanks to a Spanish citizen's complaint against Google Spain and Google Inc, on the grounds of the “right to be forgotten”, that triggered the update of the obsolete European Data Protection Directive to better accommodate for the protection of personal data on a globalized digital environment. Whilst the General Data Protection Regulation is being adopted in 2015, it will only be fully implemented in 2017. It should go without mention, however, that institutional enshrinement of personal data protection without social participation is not enough guarantee our interests are secured. This is a defining period, during which politically organizing the digital workers can play a decisive role in counteracting the lobbying of services which see their business model menaced by the adoption of updated regulation. And, while we are at it, why not play a decisive role in the writing of these laws and demand citizen access to the process?

Another citizen initiative unfolding at the moment is the Europe vs Facebook lawsuit, and initiative by lawyer and activist Max Schrems. Europe vs Facebook attempts to answer the question ‘Are EU Data Protection laws enforceable in practice?’, with a focus on how Facebook handles user data. In October 2015, the Court of Justice of the European Union ruled that the Safe Harbor Agreement, a legal framework put in place to facilitate the transatlantic transfer of personal data supposedly in compliance with both EU and US laws and to which Facebook abides, is invalid. This ruling was justified on the grounds of insufficient protection of the data subjects' (that would be us) rights. Another lawsuit filed by Schrems against Facebook is a class action counting with the participation of 25.000 Facebook users. Although too late to participate in the lawsuit, interested data subjects might still register their support at FBClaim.com. Albeit being dismissed by the Vienna Regional Court in July 2015, an appeal to the Supreme Court was granted and results are anxiously awaited.

Fighting against these data hungry giants might not be as easy as engaging in superficial chit chat on comment boxes, or as fun as going on an hashtag rampage about adorable furry cats dancing the limbo, but we have to look at the bigger .gif and realize the deeper, long-lasting consequences our data slavery as good as guarantees.

And these, though sparse, but very significant citizen victories should only inspire us to join our networked forces and use our indispensable status as leverage to achieve better working conditions and eventually disrupt the market which preys on our affect, social life and personal data.

After completion of her bachelor studies in Graphic Design, Lídia Pereira [Portugal] became intrigued by the friction between digital utopias and material realities. Her current work is concerned with the political organization of labor within digital economy, presenting a focus on the power structures governing online behavior. This INC Longform originated in her Piet Zwart Institute graduation thesis.

Bibliography

Alexander R. Galloway, Protocol: How control exists after decentralization, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2004.

Katie Hafner & Matthew Lyon, Where Wizards Stay Up Late: The Origins of the Internet. New York: Touchstone, 1996.

Mirko Tobias Schäfer, Bastard Culture! How User Participation Transforms Cultural Production, Amsterdam University Press, 2011.

Nikolas Rose, Governing the Soul: the Shaping of the Private Self. Second Edition. London: Free Association Books, 1989.

Andrew Ross, ‘In Search of the Lost Paycheck’. In Scholz, T. (ed). Digital Labor: The Internet as Playground and Factory, New York: Routledge, 2013.

Images

At last... A Community Memory! Four-page center inset in the Resource One Newsletter, Number 2, April 1974 pp 3a: http://www.well.com/~szpak/cm/cm-1-atlast.jpg

At last... A Community Memory! Four-page center inset in the Resource One Newsletter, Number 2, April 1974 pp 3b: http://www.well.com/~szpak/cm/cm-2-Leopolds.jpg

At last... A Community Memory! Four-page center inset in the Resource One Newsletter, Number 2, April 1974 pp 4a: http://www.well.com/~szpak/cm/cm-3-theories.jpg

Facebook Revamps Page Suggestions, Adds Page Invites Manager to Page Browser: http://www.adweek.com/socialtimes/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2011/04/Recommended-Pages-Done.png

Grant's Drawing of a Target Sociogram of a First Grade Class (from Northway, 1952): http://www.cmu.edu/joss/content/articles/volume1/images/fig12.gif

Social Graph - Application on Facebook: http://asawicki.info/files/facebook_social_graph.jpg

Zuckerberg's Social Graph: http://images.bwbx.io/cms/2012-05-18/bw21_features_zuck4_950f.jpg

Immaterial Labour Union logo: http://ilu.servus.at/Lidiacatalogthumbnail.png

Terms of Servitude: http://ilu.servus.at/termsofservice.jpg

Immaterial Labour Union Issue #3: http://ilu.servus.at/capazine3.jpg