This post is part of a research project in the Minor Designing User Research at the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences about the difference between apps of traditional and digital banks, specifically in terms of user expectations, experience and privacy. A first overview was already posted in Dutch. This post features the final results of the project.

By: Nathan Sokoloff, Maria Molenaar, Paul Hesling

First, we would like to introduce ourselves: We are Maria Molenaar, Nathan Sokoloff and Paul Hesling and we are students from the study Communication & Multimedia Design and we did a minor in Designing User Research. In this minor, we did a research project focussed on digital versus traditional banking. During this research project, we got guidance from Inte Gloerich from the Institute of Network Cultures.

Because we did not have much knowledge about banks and online banking we were given the reader: Moneylab, Overcoming the hype. This reader is about a cashless society, blockchain, digital currency, fintech and much more. With this reader, we got more information about the current and upcoming topics surrounding transactions, banks and online banks. From here we made a choice to do research about traditional versus online banks. Our research would focus on the aspect of privacy.

The first part of this research has already been published on this website as a blog post. This was primarily focused on the differences between traditional and online banks. Check it out here.

In this second part of the research, we have done desk research to find out more about the privacy policies, designed our own mapping workshop and arranged interviews to get a better understanding about the beliefs and facts surrounding privacy. We hope you enjoy the read.

Our Question and Approach

From comparing traditional and digital banks to the subject of bank privacy.

The banking world has been quite tumultuous lately. In recent years, considerably stricter or renewed laws have been announced and put into effect. Like de GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) that was put to work at the beginning of 2018. It is mostly known as the privacy law and aims to harmonize data privacy laws in the whole European Union. In a nutshell, GDPR defines personal data as “any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person.” Name, address, email address, financial information, etc. But it also can include data related to your digital identities, like geolocation, IP address, historical browsing, and cookies.

“I don’t read privacy conditions. Because I think it is well regulated by NL with the GDPR law. “

Interview participant.

Over the years, there has already been a big debate around privacy in relation to social media, especially Facebook. And if we talk about privacy on social media, a well-known statement that many people share is the feeling that they have nothing to hide.

“The data market has become the engine of the internet, and these privacy policies we agree to but don’t fully understand help fuel it.”

We Read 150 Privacy Policies. They Were an Incomprehensible Disaster. Kevin Litman-Navarro, New York Times.

But do we have the same mental attitude toward privacy in relation to banks? Do we trust that the government will strictly regulate the banks and how they deal with our data? Or are we superstitious and protect our data as much as we can? And how well do banks really inform us on these topics?

Our main research question is: What is the user experience of privacy in traditional banks (incumbents) and digital banks?

Preliminary Research

In our preliminary research, we took a good look at the privacy statements of both types of banks. Our goal for this research is twofold:

- Establish an understanding of how banks regard and communicate privacy within their organization.

- Explore and document how consumers are experiencing this privacy

These themes are especially interesting when put in the light of the new EU-directive “Payment Services Directive 2” (PSD2), a series of regulations that give consumers more control and shareability when it comes to personal bank account data and transactions, whilst diminishing the exclusive control banks have over transactions. Informative consumer-centred PSD2 content is available but has received negative feedback from the community. Many users disagree with the nature of the system and and praise cash as an alternative. Also, a degree of distrust is present. Some popular comments touch on the issue of privacy.

“Vanaf nu zijn je bankgegevens niet zo geheim meer”, NOS op 3, YouTube, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RprAs2hCR7Q

In our attempt to understand how banks have established privacy on their platform, we compared the privacy statements and policies of traditional banks to digital banks. Additionally, we documented in what manner the platform is communicating or guiding customers regarding privacy.

Area’s we observed:

- What type of language was used to communicate privacy statements?

- What data does the bank collect from its customers?

- What data is shared, and with whom?

- Is the bank allowed to alter their statements at any time?

- How do the banks attempt to teach their customers how to engage with their personal data on the platform?

- In what way is the bank responsible for the data?

- How long do banks keep personal data of their customers?

One of the notable findings was about storing personal data. In analyzing the privacy statements of the two types of banks, we noticed that traditional banks, like ING and Rabobank, state that they can ‘archive’ customer data, formally indefinitely. Knab and Bunq bank have a different approach and only show the maximum time allowed for storing data. In some cases, like Bunq, the organization is extremely transparent about what third parties personal data can be shared with. In contrast, ING bank only discloses the type of party that can be shared with (e.g. “researchers”) without naming the exact party. However, it could be that when customers demand their data from a bank, this information must be disclosed.

ING (left) and Knab (right) have a different approach when it comes to storing personal data. Knab has a detailed explanation on-site on how long data is stored. ING has a less comprehensive view, but does offer a downloadable PDF with similar information.

“Hoe lang bewaren we persoonsgegevens?”, ING,

https://www.ing.nl/de-ing/privacy-statement/hoe-lang-bewaren-we-persoonsgegevens/index.html; “Privacy statement “, Knab, https://www.knab.nl/privacy/privacy-statement.

Methods Used

Interviews & Empathy Map

The first method we used was interviewing, we used this because we wanted a have a variety of data about the knowledge and opinions about our topic. To approach them “face to face” with questions, you can dig in particular questions more if the participant said something interesting. The people who we have interviewed are in the age range from 18 years to 69 years old, all of the participants have one or multiple bank accounts. questions we asked the participants:

- Are you familiar with digital banks and can you tell something about it?

- Do you ever read the privacy conditions of your bank?

- Are you willing to submit personal data for improved banking services?

- Do you think that a traditional bank is safer than a digital bank or vice versa?

- How do you feel about your privacy when you give your data to a bank?

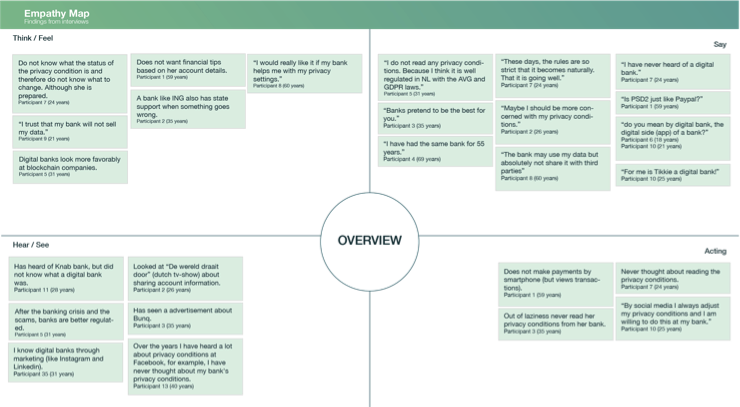

After the interviews, the insights were mapped into an empathy map. This is a collaborative tool to gain a deeper insight into the customers. Much like a user persona, an empathy map can represent a group of users.

Insights

The image above is a merging of different empathy maps with the most interesting insights shown. We immediately noticed that many respondents did not know what a digital bank was. People either had never heard of the term, though it was a service from a traditional bank, for example, the ING app, or that Tikkie was a digital bank. One of the participants knew that Knab bank existed but did not know that this is a digital bank. When people did know about digital banks, this was mostly because of marketing.

Another insight is that people take privacy for granted and assume that banks handle their data well. They expect that the law regulates banks and that banks cannot pass on their data to third parties. But bank do pass on data, and by doing this they might even lose track of the data. Most of the participants haven’t thought about reading or making adjustments in their privacy conditions, simply because they trust their banks or out of laziness. But when you ask them: would you rather pay for improved services or would you provide more personal details? Then they say that they would pay more. This indicates a contradiction in the confidence they express earlier towards the banks. Why would they not want to provide more information if the bank did not do anything unsafe with it?

Mapping Workshop

With this method, we wanted to get insights into what people already knew and what they thought about privacy with traditional and online banks.

The sessions

We held three sessions with four different participants. We made two mapping papers: the first about traditional banks and the second about digital banks. These papers had 4 axes were the participants would lay out the cards we gave them. The 4 axes were from left to right: Not important – Very important, and from top to bottom: I know much about – I know not so much about. The cards we gave them had phrases like these on them:

- A bank is a trusted institute

- I have access to cash money

- My bank has a physical location

- By sharing more personal information I get better digital services

- I can easily read my privacy policy and the description is clear

Before we began with the mapping session we gave every participant a quick explanation about how the session would go. In our interviews, we learned that not many people knew what a digital bank was, so we explained that too.

The insights

As expected from our interviews we noticed that people did not know that much about digital banks but found it very important that they can be trusted. To our surprise, people found it less important to get personalized services and recommendations from digital banks.

Our participants knew a lot more about traditional banks and could, therefore, talk a lot more easily about their own experiences and opinions. With traditional banks, the outcomes were more in line with our expectations. We saw a trend in participants who would find it very important to be updated with the latest privacy statements but know very little about it. When we asked them why, they said: “because it’s too hard to read!” What we found interesting is that both the traditional and online bank mappings pointed out that participants would find it important to have control over their own data.

Data Visualisation with Gephi

Gephi is a data visualisation tool we used to map hashtag data from Twitter. Our aim was to learn more about the concept of privacy and banking as perceived through social media. We wanted to know how the concept resides online and find out what types of discourse are trending on the topic.

Gephi is a data visualisation tool we used to map hashtag data from Twitter. Our aim was to learn more about the concept of privacy and banking as perceived through social media. We wanted to know how the concept resides online and find out what types of discourse are trending on the topic.

Using the DMI-TCAT tool, we scraped twitter for a handful of specific hashtags. The system automatically finds related hashtags on Twitter that have (often) been used in conjunction. It’s a great method to learn about additional topics of importance related to a query and has helped us identify surrounding themes that were impacted by our search.

Our dataset was based on the following hashtags;

#digitalbanking, #digitalbank, #openbanking, #futureofbanking, #bankingasaplatform, #psd2

Insights:

- #openbanking is the most prominent hashtag used in the set. Open banking is a financial service model that uses open API’s that external developers can use to create additional financial services.

- Many emerging themes are in the realm of Fintech (financial technologies). In addition, #fintech is the most prominent emerging hashtag that was not part of our query.

- The hashtag #blockchain emerged with strong connections to #fintech, #banking and #ai, but less affiliation with our queried hashtags. The data signifies a relationship between blockchain and emerging financial technologies. The hashtag also shares a significant connection with #digitalbanking and #openbanking, suggesting speculation and discourse on blockchain and digital banking and/or open banking.

- Although #PSD2 had a significant weight in the data set, it doesn’t make strong connections with other hashtags in the dataset. This implies that the topic is discussed on Twitter, but not often in combination with other emerging themes. When combined with other hashtags, #PSD2 is used most often in conjunction with the hashtags #openbanking, #fintech and #banking. The first, and to a lesser extent the second are likely to be used by organisations instead of end-users because they are more like jargon. Surprisingly, PSD2 is somewhat represented as a standalone topic in comparison with other topics and is less connected to privacy-related topics.

- Some emerging types of financial technologies came forward from the dataset, such as #insurtech. Insurtech refers to innovative technologies designed to create effective and efficient insurance industry models. Insurtech startups, for example, are using AI to find correct individual policies and coverages.[1]

- The only significant presence we found in the dataset with regard to personal user privacy, is through the @privacyfirst twitter account and it’s mentions/shares. Even though the presence is minimal, the content is very relevant; it’s a callout for a public debate about PSD2 and privacy with political party Piraten Partij, signifying a (political) movement safeguarding user privacy in the light of PSD2.

- Issues surrounding privacy are present, but incredibly underrepresented – at least on Twitter.

@privacyfirst

“Bankgeheim: publieksdebat over #PSD2 en #privacy met @privacyfirst & @ Piratenpartij, 20 juni as. Den Haag https://t.co/7VxO2hVHu7”

The concepts digital banking, open banking and PSD2 are heavily connected to upcoming fintech services. This is no surprise. What is surprising, is the lack of privacy-related data that emerged.

Most of the data seems to be coming from the industry itself, not from end-users. This is to be expected, but emphasizes that both citizens and politicians are not discussing these topics with the same frequency and are somewhat underrepresented in our data set – and perhaps in the real world. In short, the data speaks more about business then it speaks about people. This is a valuable insight that strengthens the notion that although banking services are increasingly becoming “human-centered”, the expression on Twitter mostly revolves around the business(models) and commercialized financial services. What does human-centered design mean if you’re a fintech company?

Speculating on the future of privacy

What we see is that customers expect banks to be trustworthy. People still treat banks as an institution that will act to the best of their knowledge, and even after all the commotion in the economic crisis people don’t deviate from this pattern of expectations. In combination with the laws that have been drawn up by the government, people feel that their personal data is safe with the bank. But with the increasing automation and the growth of fintech companies, a clear plan will have to be made to guarantee the safety of privacy and personal data. When you look at the interest of social media companies in customer data, you can ascertain that when there is a possibility to get financial data from customers, this interest will only grow.

Seeing how valuable financial data is, it is possible that in the future, people will have to choose how much data they will share in order to get more interest or discount on certain bank services. Because of this, it is important that people now gain more control over the data they share with the bank. But also, banks should be more transparent about the (financial) data they collect, have, and share about their customers.

Our research shows that people have not heard much about the phenomenon of digital banks, yet they are companies that are growing rapidly and are conquering an ever-increasing share of the market.

The rapid changes resulting from innovation can lead to an increase in pro-cyclicality and volatility in financial markets, new market concentrations and greater operational risks. The viability of traditional institutions can also come under increased pressure.

De toekomst van banken, Economisch Statistisch Berichten Dossier October 11 2018

It is not certain whether the one will exclude the other. We suspect that people are not yet ready for an entire digital financial market. Tradition and trusting the bank can still weigh too heavily. The digital banks are, and will, pressure the traditional banks to be more innovative. Apps that are operating on the banking sector from the outside will have an influence on banks as well. It is unclear how the diminishing traditional bank system and PSD2 and its resulting user responsibilities will impact our daily lives, but from our research, it is clear that the general public has little knowledge about the emerging responsibilities on personal data and personal data governance.

[1] Bron: “Insurtech”, Investopeda, 2019, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/i/insurtech.asp