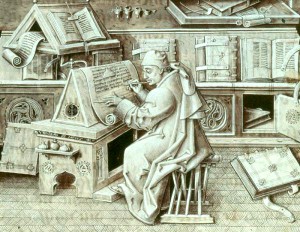

1. The history of the transmission of human knowledge carried by the historical libraries and archives through the centuries, is a good context in which to observe in the media the process from the oral tradition, passing through the physical actual writing, now leads to digital format. The first to express the changing times in a new media were the medieval scribe monks, who ensured the preservation of not only religious, but also historical, literary and legal information, by transcribing onto paper.

A few weeks ago I was reading an italian newspaper when something leapt out from the page (it was an article written by Marco Carminati in La Domenica del Sole 24ore, 23rd september 2012): starting from October, the Vatican Apostolic Library together with a corporate called Emc (which deals with data storage) will launch a huge project of digitalization and online release of eighty thousand vatican codices “a very high resolution ‘photograph’ of each page will be made and stored in digital format for preservation and consultation”, says the president of Emc Italia, Michele Liberato. Of course it is more or less inevitable to see those who will be involved in the project as some kind of “digital scribe monks”. However, this simple and ironic parallel actually says a lot.

In the Middle Ages the amanuensis monks were made to convert ancient knowledge onto paper by the wish to make these “data” permanent; if this means new opportunities create new needs and vice versa, what happens now? The digital format, intangible by nature, among all its possibilities, may well provide safer storage of information? It depends on the point of view.

What happens conversely to the modes of transmission, interpretation and production of information? This is definitely a more interesting area to explore.

The credit of having “invented” the concept of preservation of knowledge goes to the scribes. The printing press was another important turning point for communication, it made written knowledge transmissible and so accessible to many in the space of the present and across the time, through the coming centuries; we know very well how radical the changes in cultural processes brought by this new “device” have been: the modern book was born.

Today we are only at the dawn of the digital book. It is a process that implies not only changes in the book as an object, but above all changes in the concept of transmission of knowledge itself. The work of digitalization of all human knowledge begins now.

2. One thing I find particularly interesting is observing something that at first sight and superficially seems like a reaction, a sort of de-digitalization; I believe that to be rather a way to look for another possible interpretation of the whole process, as it was not a linear evolution, but something more complex in which sometimes coming back is necessary in order to understand better all the dynamics. Furthermore, some concepts like ‘writing’, ‘reading’ and ‘production and transmission of information’ risk remaining too vague if not linked to a speech on media, not only the new ones, but also those already well-“tested”.

Maybe digital can be understood by retracing our steps. What happens to the physical object and traditional media with digital? Therefore the concept of de-digitalization should be more like rethinking the physical object through digital.

There are many experiments in de-digitalization with different approaches and different concepts at their basis, especially in the field of visual arts.

The Art of Google Books is a project which collects on a tumblr blog glitch images taken from google books. In finding the anomalies and discontinuities of digitalization, the project probes the physical limits of this process, by observing from an aesthetic point of view its failure. They are both digital ‘photos of photos’, in which the non-digital, with its “noise”, is the visual lead character.

Another way, different but still part of the same discourse, is the attempt to “print the internet”. There are many examples of readers, a selection of blog posts put onto paper, a sort of “blogger’s digest”; one of these is Invalid Format, made by the art magazine Triple Canopy, a printed publication from the online magazine. Born as a questioning of the longevity of online publications, invalid format has been created to have a safe-in-paper “artful archive”: this is a totally different consideration of the safety of the digital support.

Still different is the case of projects (mostly art and design projects) which made experiments with the traditional book after the changes in the reading experience due to digital languages. In asking what will a future book look like, there is no need to stop at the simple fact that now we have the opportunity to have books on our tablets, but rather to understand what is and what has been the reading experience. The next Out of Ink interviews will deal with this issue.

Read an italian version of this post here