Interview with Lisa Parks

By Geert Lovink

In her book Cultures in Orbit (2005), media theorist Lisa Parks describes satellite technology as a ‘structuring absence’. Satellites play a key role in today’s global news industry and its “spotlighting of the apparatus” (Elsaesser). However, the key ingredient of the global live connection remains invisible. This is reflected in most of the studies of ‘the televisual’, as Parks calls the infrastructure behind the channels we watch. With Cultures in Orbit, Parks established herself as probably one the first ‘satellite theorists’ who analyses this technology from a critical, cultural perspective.

The book opens with a chapter on the 1967 global TV show, that explicitly featured the satellite and promoted the idea of ‘global presence’. Even though the event was neither live nor global, according to today’s standards, debates around the early satellite days remind of the current Internet Governance discussions, which take place around the World Summit on the Information Society. In the same year, 1967, UN members signed the Outer Space Treaty, prohibiting national appropriation of outer space, while discussing the role of third world countries, which, at the time, did not possess satellites at all. A chapter about the Australian Imparja TV and aboriginal TV initiatives is also included. A different use Parks found in Alexandria, Egypt, where satellite pictures were used in the excavation of Cleopatra’s place.

The book opens with a chapter on the 1967 global TV show, that explicitly featured the satellite and promoted the idea of ‘global presence’. Even though the event was neither live nor global, according to today’s standards, debates around the early satellite days remind of the current Internet Governance discussions, which take place around the World Summit on the Information Society. In the same year, 1967, UN members signed the Outer Space Treaty, prohibiting national appropriation of outer space, while discussing the role of third world countries, which, at the time, did not possess satellites at all. A chapter about the Australian Imparja TV and aboriginal TV initiatives is also included. A different use Parks found in Alexandria, Egypt, where satellite pictures were used in the excavation of Cleopatra’s place.

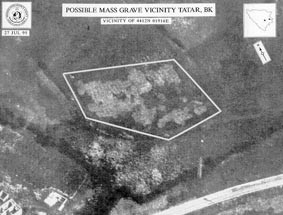

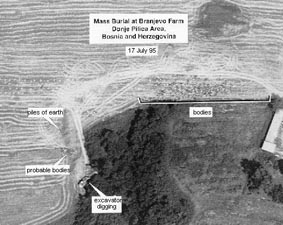

The most interesting piece of Cultures in Orbit forms a reconstruction of the role that satellite ‘witnessing’ pictures played in the immediate aftermath of the 1995 Srebrenica mass killings in Bosnia. Remote sensing evidence of mass graves, broadcast on the US networks, contributed greatly to US military involvement and the following Dayton agreements. In 2001 Lisa Parks went to Bosnia, to shift her position, “to move my eyes from the orbit to the ground,” experiencing a “fantasy of proximity.” The story illustrates how easy it is to visit a historical location and yet how difficult is it is to bring together techno proximity with the materiality of the actual location, symbolized by a shoe she finds in the fields. Parks’ case studies show the potential of thinking through certain technologies, instead of merely watching the final products that we, media consumers, are being offered. Without a trace of techno-determinism, Cultures in Orbit proves that it is possible to tell stories and develop new media concepts.

Lisa Parks, PhD, is Associate Professor of Film and Media Studies at the University of California at Santa Barbara. She is co-editor of Planet TV: A Global Television Studies Reader (NYU Press 2002) and has published essays in several book collections and in such journals as Screen, Television and New Media, Social Identities, and Ecumene. She has taught as a visiting professor in the School of Cinema-TV at USC and at the Institute for Graduate Study in the Humanities in Ljubljana, Slovenia. Parks teaches courses such as global media, television history, new media theory, video art and activism, war and media, advanced film analysis, and feminist media criticism. She is also co-producer of “Experiments in Satellite Media Arts” with Ursula Biemann at the Makrolab (2002) and “Loom” with Miha Vipotnik (2004), and has been a co-investigator in international funded projects including the Missing Links Research Project (UCSB-Utrecht) and the Transcultural Geography Project (Zurich-Cologne-Ljubljana). She has just started to direct the Global Cultures in Transition research initiative at UCSB’s Center for Information Technology and Society and is currently a research fellow at the UC Humanities Research Institute.

GL: So far, the satellite has barely existed as an object of interest, not even within television studies or media theory. Though widely used, the apparatus remains invisible, in the background. As a consequence we don’t know much about its inner architecture. You’ve been engaged for years with satellites. Did you get to know them?

LP: I have always been interested in the insides of machines because they confound me. I’m much more of a media and cultural analyst than a historian of technology, though, so the knowledge I have about the engineering and design of satellites is somewhat limited. Each satellite has its own technical and socio-cultural history and it is difficult to make generalizations, but I think of them as floating balls made up of combinations of coordinated systems involving energy (solar panels and batteries), communication (antennae and transponders), optics (cameras and sensors), and navigation (thrusters). I would love to visit a clean room where a satellite is being assembled and I once met a man on a plane who gave me a photo of himself embedding a part in a satellite and invited me to visit his facility. I have yet to track him down. Rather than focus on inner architecture in my book I wanted to explore the satellite’s outer effects. There are many books about satellite engineering and design but very few about satellites and society or culture — what does this suggest?

GL: So how could we get a sophisticated satellite theory?

LP: First we need more description and analysis of the ways satellites have been used. We know they are used for signal distribution, remote sensing, espionage, global positioning, astronomical observation, and so on, but we still don’t know satellites by name. So in addition to delineating their uses in greater detail perhaps could begin to refer to satellites by name and know who owns them and how they are used. For instance, we could discuss a communications satellite like Hotbird 3, which was manufactured by a UK company called Matra Marconi, is owned by French company Eutelsat, and was launched on September 2, 1997 by the Ariane V 99 rocket. It’s footprint covers Europe and North Africa and extends as far east as Moscow and Dubai. Which signals pass across its transponders? Where do they emanate from and where do they end up? Hotbird 3 carries hundreds of television and radio channels from countries including Italy, Syria, Yemen, India and Thailand just to name a very few. (For a list of all signals carried by Hotbird 3 see http://www.lyngsat.com/hb3.html.) In short, before we get to a sophisticated satellite theory we need to do the grunt work of mapping out and understanding the material conditions of the satellite economy. Then we can begin to postulate theories about the ways satellite technologies restructure global time/space and culture.

We could do the same kind of thing with a remote sensing satellite. Remote sensing and satellite espionage are not just scientific or military practices ? they have social and cultural implications. Who is taking photos of the earth? How are those photos being used to produce knowledge about the planet? Who is using the earth’s surface to generate profit? Who is using it to produce spheres of influence? There is a need to re-examine the global material conditions through the rubric of satellite technologies. We need new world maps that show how footprints override nation-state boundaries, how transponders create new neighbors, how orbital views generate fields of political activity, and how the perimeter of the earth is trafficked.

GL: I understand we need more raw data before the real theorization can take off. But could we perhaps speculate and propose to read satellites as metaphors, as a new type of technological mirror? Could it be that we have entered a new collective ‘mirror stage’? The lack of common awareness seduces us to return to psychoanalytic terms and for instance speak of the satellite as an unconscious apparatus. Or should we rather not go in that direction?

LP: To think about satellites and the unconscious is interesting, but I haven’t developed any work along those lines. I think it’s intriguing to think about satellites as metaphors for a collective mirror stage, but such propositions would need to be worked through more carefully. Maybe we need a conference on satellites, culture and power to begin to collectively addressing some of these questions.

GL: Two instances cross to my mind: the launch of the first satellite, the Soviet-made Sputnik in 1957, at the height of the cold war, which caused a mass panic about the possibility to drop nuclear weapons out of space (instead of launching them with missiles). The second wave of heightened satellite awareness perhaps was during Reagan’s launch of the Star Wars program, in the mid eighties, when people realized that objects in outer space have the potential to strike the earth. Apart from these exceptions, satellites have been invisible… until migrants installed the dishes on their balconies. But let’s return to your book. In Cultures in Orbit you have chosen to describe the spectrum of satellites in terms of the (tele)visual. Telecommunications satellites are absent. Why? Aren’t all satellite digital these days? Television satellites ‘reflect’ data, much in the same way as telecom satellites do. They all ‘sense’ or ‘reflect’, more than they ‘see’ or ‘listen’. What was your reason to focus on the (tele)visual?

LP: I focus on the televisual because I was trained in the field of television and cultural studies and I have always thought that we have accepted too narrow a definition of what “television” is or could be. In my book I analyze different sites of convergence to argue that the televisual is not only as a system of global commercial entertainment or national public broadcasting, but a set of technological potentials that involve seeing, hearing and knowing from a distance. This is an attempt to bring the satellite and computing together with discussions of television and to challenge determinist logics that attempt to fix the meanings and potentials of technologies. Television is not only defined through its technical or internal structures but is also interwoven with language, culture and socio-economic systems that are historically contingent and as such can become sites of contestation. Developing a more discursive definition of television allows us to imagine struggling over and re-arranging these potentials rather than abandoning them in favor of a digital euphoria, which, at least in the early days, tended to ignore the historical patterns by which decentralized network communication infrastructures (whether telephony, radio, or television) had been co-opted by state, military and commercial enterprises. So, dealing with the televisual is a way of inscribing historical struggles over past network technologies within the more recent initiatives to keep digital technologies as open, undefined and flexible as possible.

In response to the last part of your question I would say that satellites are always connected to something somewhere on earth — so they do see and listen for some one and it’s a matter of investigating in whose interests they see and hear for and to what end. There is an entire field of satellite studies possible, just as we have seen radio, film and television studies develop, and more recently cyber studies and mobile phone studies. Why not satellite studies? Satellites are not just reflectors in orbit — they are actively implicated in a system of global power relations. They are tethered to institutions, places, bodies, and agendas.

GL: This again leads us again to the question why satellites are the blind spot of international media theory. Is the link to the military industrial complex a clue here? On the other hand, we could say that commercial satellite business is already 40 or so years old. So perhaps we cannot use the argument, time and again, that satellite information remains a military secret.

LP: I don’t think satellite information remains a secret. It has just not been a site of study in media studies like the screen has been. In media studies we tend to gravitate toward objects that are visible and audible, but there are barely perceptible objects like satellites that are certainly worth considering. The research that has been done is largely aligned with the history of technology or international relations and does not necessarily engage with critical theory.

GL: Should we read your approach as a call to develop a materialist theory of the televisual? The current cultural studies literature is focusing almost exclusively on representation and identity.

LP: I guess this could be one way of putting it, though scholars that focus on identity and representation often describe their work as a material-semiotic approach. There are also earlier television scholars whose work is very much invested in materialist history and criticism. Simply put, I’m interested in examining media technologies through their uses. It’s important not to draw a hard line between technologies and representation since technologies are not just physical artifacts but they are also made up of imaginaries, discourses and power relations. The technical form of television is not fixed — it shifts historically and so the televisual can be imagined and materialized in different ways. I try to stay flexible and non-essentialist in the way I imagine it as a site of history and criticism. Also, I don’t focus only on television in my research. I try to think across different audiovisual media and distribution platforms. Lately, I’ve become more preoccupied with grounded and embedded hardware. Maybe it’s a reaction to working on orbital cultures. But I did find myself writing about e-waste this past year and thinking about structured obsolescence, media ruins, and re-purposing. This involved treating the salvage yard as a site of media studies. I think there is an important challenge embedded in your question — what kinds of different materialities can be found in and around media technologies? Also, how can we continue to expand the scope and sites of media studies research beyond the screen and the living room?

GL: You have written about artists and activists appropriating the satellite technologies. One could mention Deep Dish TV, but also B92 in Serbia and Marko Peljhan’s Makrolab. Have you ever heard of people ‘hacking’ satellite channels? In the nineties there were rumors about defunct Soviet satellites, that could be ‘squatted’ before they would tumble down. Would it make sense, in your view, for alternative media to own their own satellites?

LP: I wanted to write an entire chapter on Deep Dish TV because it’s such an important story about alternative media’s appropriations of satellite technology, but I didn’t do so in part because the activists involved in Deep Dish have written about it extensively. I did write about Marko’s Makrolab a bit in the conclusion of my book as well as Brian Springers’ excellent video, Spin, which exposes what happened on satellite backhauls in the age before signal encryption. Yes, it would be great if alternative media owned their own satellites, but given the expense that’s unlikely. There were a handful of media artists in the 70s and 80s including Nam Jun Paik, Douglas Davis, Sherrie Rabinowitz, Kit Galloway and others who leased time on satellites to stage inter-continental performances and events. I have an essay coming out in the Quarterly Review of Film and Video in 2006 about this topic.

GL: Recently, BBC News announced that it has installed a new ‘delay’ technology in order to monitor incoming live feeds. From now on even live television can be controlled without the viewer having an idea about it. This happened in response to the uncensored broadcasting of the bloody Beslan school siege in Russia by Chechen fighters. Doesn’t this signal the end of the satellite age? Isn’t the ‘live’ aspect a crucial part of our global television age?

LP: The meanings of “liveness” have been regulated and controlled since the earliest days of television and arguably since the age of telegraphy. Many “live” media events are carefully planned. Perhaps a more interesting issue to bring up here is the idea that we have the capability for constant monitoring of the earth, but there is such an enormous volume of data whether live television feeds coming from various locations or remote sensing and espionage imagery that it is impossible to put this “live coverage” to use without sophisticated sorting and filtering technologies. What this means is that data mining is now necessary for live media to be of any real value. We have reams of “live media” that go directly to enormous supercomputers where they are archived so that they can be used retrospectively. Perhaps in the digital age retrospective media will replace live media. With the omnipresence of the camera both on earth and in orbit, we will move into a situation where there is bound to be some coverage of any given event happening on the earth, it’s just a matter of retrieving it.

GL: I am curious about the link between satellites and the Internet. Is there any particular relation between these two in your mind? We all probably know that Internet traffic through satellite is still expensive, much in the same way as satellite telephone.

LP: This is an interesting topic that could go in different directions. The rates for satellite internet services are starting to drop and are becoming competitive with ground-based ISPs. A use model for this in the US comes from the retired RV enthusiasts who mount their dish on their vehicle everywhere they go. They have mobile subscriptions to satellite television and satellite Internet services and can roam while viewing TV and surfing the web and don’t need to find WiFi hotspots. There are a bunch of companies trying to lure DSL customers away from the major ISPs including Spacenet, Starband, Skycasters, Infosat, VisualLink, Quiksat. (This, the by way, is analogous to the historical and ongoing battle between cable and satellite television operators in the US.) Satellites are now being manufactured for specific Internet service capacities. On August 11, 2005 a Thai company launched Thaicom 4, called “the biggest satellite in the world” and made by SpaceSystems/Loral in Palo Alto, California, in part to provide broadband Internet service throughout the Asia Pacific, Australia and New Zealand. It has a bandwidth capacity of 45 gigabytes per second and will route data through 18 gateways. As the capacity onboard satellites expands, the prices for satellite internet service will likely drop. And as users grow more accustomed to high-bandwidth there will be greater demand for services in which there are no dead zones.

There are other ways to talk about satellites and the Internet as well. Satellite images, for instance, would not have been mass circulated in the same way without the web. There are portals, mapping services and archives that make satellite images more widely available. Consider how google maps has hardwired satellite images into its service. It is also possible to track satellites in orbit at a web interface, to find lists of television signals carried on a particular satellite, or to learn of future launch dates. So the web has become a gateway for learning more about satellite technology and the practices that help shape it.

GL: Could you tell us something about your engagement in Eastern Europe? How do look at ‘New Europe’ from the frontiers of former times, California, where you teach? Do you find it hilarious, perhaps comfortable to spend time amongst the former Yugoslavs? It is a theory-rich region. Can you use certain concepts from there in your own work?

I first went to Bosnia in 2001 to do research for chapter three of Cultures in Orbit, which examines the US’s circulation of satellite images of mass graves in Srebrenica. It was a difficult trip, but I met some dear friends along the way and became more aware of my own need to track and study what the US does in countries elsewhere. I have been back to the region many times since then and have lived in Slovenia and Croatia during the summers. I have been researching US/NATO destruction of the Yugoslav broadcast and telecom infrastructure and the replacement of it with “liberalized” and “democratic” media systems largely owned by Western (US and European) conglomerates. I became interested in the region in part because of its political history. It amazed me that ethnic communities came together to form Yugoslavia after the horrors of WWII. The country also remained non-aligned movement during the Cold War and developed a unique version of socialism. The recent war was tragic and discussion of it in the US has been largely eclipsed by Afghanistan and Iraq. I see these wars as interrelated, however, and as part of an episodic pattern of US aggression and sabotaged diplomacy.

You’re right to say that it is a theory-rich region and I hope concepts will inform my future work. I don’t find it “hilarious” to spend time with former Yugoslavs. I find it energizing. There is definitely a long distance between former Yugoslavia and California, but such distances can be illuminating. California is not just America’s playground as it may sometimes appear. It is a state with an enormous industrial sector, ethnic communities from around the world, and complex systems of class stratification. In Los Angeles there are ethnic tensions that may parallel the kind that led to war in Yugoslavia. It’s interesting to think about what prevents war from erupting in this country. The boundaries of Europe are certainly changing, but from the perspective of the US (and perhaps from other former colonies) they have never appeared as fixed since European extensions and migrations led to the formation of our country. I had never thought about it in the terms you pose, but perhaps it is true that I am sitting in the “American frontier” (now governed, ironically enough, by a Schwarzenegger from the heart of old Europe), reflecting upon the new frontiers of Europe. What would happen if formerly socialist states in Eastern Europe collectively decided to become a federation rather than to become part of the EU and NATO? I realize this is a far-fetched idea, but is conformity with Western Europe necessarily the most desirable goal? To what extent are Eastern Europeans involved in determining the processes and parameters of their integration? How will difference be preserved across the New Europe? What borders and regulatory systems are defining the New Europe? How are media cultures and technologies implicated in their implementation and maintenance? Working between California and former Yugoslavia has given me an oblique perspective on these issues, and has led me to understand “New Europe” not only as a set of material conditions on the continent across the Atlantic, but also as an ongoing conceptual challenge to those who are imagining, creating and/or reforming political administrations in the world.

GL: Where would you ideally like to take your work on satellites? Are you working on a next book? I could imagine that you have moved on a fair bit in your thinking from Cultures in Orbit.

LP: I am working on an essay about the lives of three different satellites, comparing their histories, uses, positioning, effects, and evaluating why they are such obscure objects in media studies. I also just finished a project called Postwar Footprints about the way satellite and wireless footprints have been used to re-map parts of former Yugoslavia and link these regions to conglomerates in Western Europe and the US as part of European integration. This research is part of an art exhibition that opens at KW in Berlin on December 17, 2005. In some respects the detachment and invisibility of satellites has led me to become more interested in physical infrastructures. I’m writing a new book called Mixed Signals: Media Technologies and Cultural Geography, which explores emerging media systems in fringe areas — areas on the edges of urban space and networked infrastructures. Some of these places might show up as dark zones in a composite satellite image of the earth at night. I’m interested in exploring the different atmospherics that form in areas that are either heavily networked or not very networked at all. Perhaps this is because I am fundamentally suspicious of integration as a political, economic and cultural goal and I think there is much to learn from areas that maintain some detachment and autonomy in a world that can be interconnected. I might even call these areas satellites in a kind of metaphoric way in that they exist around and in relation to centers of power (whether financial, technological, or cultural), but are distinct from them. So the satellite will definitely remain in my work, but it will inevitably mutate and take on different (sometimes metaphoric or metonymic) forms.

—

Lisa Parks, Cultures in Orbit, Satellites and the Televisual, Duke University Press, Durham/London, 2005.

Selected links:

Biographies:

http://transliteracies.english.ucsb.edu/post/research-project/project- members/lisa-parks

http://www.filmstudies.ucsb.edu/people/professors/parks/

Censored 2006 yearbook: http://www.projectcensored.org/

Transcultural Geographies: http://www.tc-geographies.net/

UCSB Transliteracy project: http://transliteracies.english.ucsb.edu/category/research-project/

Deep Dish grassroots satellite project: http://www.deepdishtv.org/

plus a bit of its history: http://www.papertiger.org/index.php?name=roar-chap10

Marko Peljhan’s Makrolab: http://makrolab.ljudmila.org/current/

UCSB’s Center for Information Technology and Society: http://www.cits.ucsb.edu/