What will happen to web cinema as we shift from learning to see and how to feel to learning how to participate in this new electronic space of modernity?

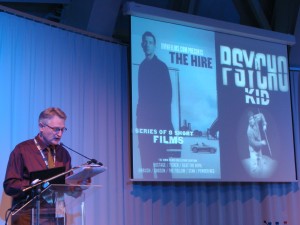

Andrew Clay is the first speaker in the morning session and talks about web cinema; Mind the Gap! He is lecturing in Critical Technical Practices at the Montfort University, Leicester and program leader of BSc (Hons) Media Technology in the Faculty of Computing Sciences and Engineering.

Andrew never heard about Video Vortex before, nevertheless he gave an interesting lecture closing ‘prosumption’ (producers and consumers) and widening between online moving image participation culture and traditional theatrical culture.

Technology has been used to materialize the use-value of film – film as aesthetic experience commodified. BMWFilms.com is an example of how we engage with expanded cinema as viewers and collectors of new forms, new genres that are at the same time old forms – the new as the ever-same of modernity as conceived by Walter Benjamin. SWK culture demonstrates participation in production as imitation of the strategies of traditional media.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LbOhDK1MKm8[/youtube]

The web via the internet is a gateway and a delivery system for film as material digital files that can be seen as resonant cultural objects, ‘fetishes-on-display’ in the web arcades. The web is also a ‘cinema of distractions’ and ‘attractions’, a digital playground allowing playful enchantment of utopian non-work and the hybrid work-leisure of user-generated content achieved through proximity to electronic machines, and this is where our hopes and fears for web cinema are made material, where our love of film is tested.

Web cinema shows us that we should be fearful about the exhibitionism of online audio-visual culture. The BMW Films advermovies mobilize Hollywood resources to web short film production bringing viewers into new relationships with advertisers. The ability to make films available to others is greatly extended, but participatory film production is not inherently progressive. One might hope that participant production will bring progressive forms of more democratic media, and certainly there are interesting experiments such as A Swarm of Angels, a ‘groundbreaking project to create a £1 million film and give it away to over 1 million people using the internet and a global community of members’ So, there is still the possibility that we might become trained in good habits.

James Provan a Scottish student, songwriter and video producer, uses especially stop motion techniques. The stop motion animation Pancakes took him 90hours to make.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UG5gO4nlLRQ#watch-main-area[/youtube]

In terms, then, of our symbolic engagement with films as commodities, we have used technology to materialize the aesthetic experience of cinema-going. I grew up watching films on television and I learned to love film. I received a film education watching a range of films from different cultures and historical periods in my ‘home cinema’ as well as visiting public cinemas. In both cases the engagement with the physical existence of film as celluloid, and the series of commercial exchanges associated with it were quite remote. They were more experiences than material engagements with physical objects. The introduction of the videocassette recorder (VCR), films on Video Home System (VHS) tape and subsequently on disc formats began to change this.

Since the introduction of the VCR, it is widely possible to ‘possess’ film, or at least the right to own a viewing copy. Subsequently, the cinematic heritage has developed more physically through the ownership of films in personal video collections as well as a memory-based recall of viewing experience. This physicality, of ‘getting our hands on’ film, is further developed using the web and the ‘next-point’ of the technological materialization of the film and video experience – mobile devices that can store downloaded moving image products. Television and the computer have been used to bring cinema into the home, and mobile devices such as phones, laptops, PDAs and multimedia jukeboxes are bringing cinema into new public spaces outside of cinemas. The web, like television, is not just a viewing space of aesthetic experience but it is also the source of material objects that can be saved and archived. The web continues the expansion of cinema from experience to materialism through the downloading of films to the hard drives of the PC.

Furthermore, in contradiction of the common view that digital media promote dematerialization, digital technologies such as the web do not dematerialize film as commodities, but instead allow them to be re-materialized as part of a historical process, most recently subject to the conditions of ‘hypercontextualisation’. Peter Lunenfeld (2002) uses this term to identify the real interactive potential of cinema and new technologies whereby the film text is just one element in a wider network of intertextual commodities such as DVDs, videogames and websites – a condition of marketing, promotion and responsive consumer participation.

Benjamin recognizes that there was a growing trend for readers to become writers in published media that began in the press with letters to editors. In the same line of argument he points to the progressive potential of film to offer ‘everyone the opportunity to rise from passer-by to movie extra’ so that ‘any man might even find himself part of a work of art’ (1935: 114). However, the development of video and computer technology has facilitated a level of participation in cinema that goes beyond the ability to appear as oneself in a film. Digital video technology enables the production of web cinema and web technology provides the distribution channels and exhibition spaces. The real ‘jolt’ of web cinema is the invitation to participate so that spectators become film-makers just as readers have become writers.

Andrew lectures also about the departure from the screening culture of production and consumption. Advocating ‘de-participation’ – rolling back of video interpersonal, social media communication of online video and the promotion of the web as a modified theatrical screen culture. Within this topic he shows a video of Howard Rheingold used as a social media communication of which he was quite shocked about. The movie is about learning to participate – teaching media literacy, interactivity and participation begins early.

He concludes with: ‘I would like more WeScreen and less YouTube’.