What struck me about visiting the Beeld en Geluid Instituut (the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision) in Hilversum, was how tidily the country has consolidated one of the largest audiovisual collections in Europe – 700,000 hours of national radio, television, film and music. Because the Netherlands’ broadcasting stations reside a few kilometers from the vault that ingests their content on a daily basis, preserving much of the Dutch media heritage becomes a streamlined process in one neat location.

Three years ago, Sound and Vision made the case to the Dutch government that the archive could increase its accessibility to researchers, artists, and the public by digitizing its collection, and that it had to, given the deteriorating conditions of some of its celluloid holdings. In 2007 the Institute secured 154 million euros to launch Images for the Future, a massive project that generates pixels out of its celluloid and tape holdings.

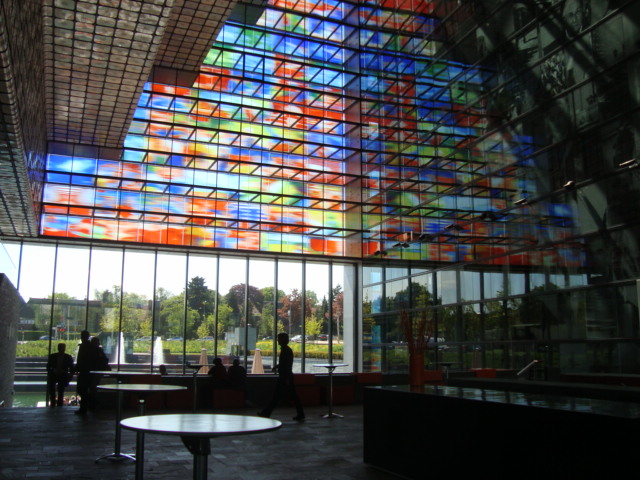

I interviewed Maarten Brinkerink at Sound and Vision in May, touring the impressive cube-shaped glass enclosure that houses its vault, the digitization projects, offices, and Broadcasting Museum. Maarten works in the R&D department, the branch that brainstorms projects encouraging broad public reuse and access to the digital materials, and he told me more about the endeavor.

What case did Sound and Vision make to secure this public funding for Images for the Future?

If we don’t digitize material within ten years, according to the research, a large proportion of the collection will vanish. Our analogue assets are literally decaying, for instance some produce an acid that eats the film material. So a proposal was made for a mass digitization project along with the Nationaal Archief (Dutch National Archive) and EYE Film Institute Netherlands to preserve and digitize a core collection of the Dutch audiovisual heritage. We argued that if we preserve the material now, we’ll be able to continue to provide access to it in the future – an investment repaid through future societal and economic benefits. As a result a large portion of Sound and Vision, Nationaal Archief and EYE will be digitized within seven years. We’re halfway through the project, with three and a half years to go.

How is digitizing so much material changing the role of archival institutions such as Sound and Vision?

I think the future mission for institutions like an archive is not only using expert knowledge to safeguard material, or to provide the most accurate descriptions, but to also construct meaningful networks out of our shared cultural heritage. We need to leave behind the idea that we as an institute are an isolated node of expertise. Material is way more interesting and meaningful for our audiences if its viewed in relation to other sources, if we offer content and contexts that can be combined in many ways to give a more complete story. These different contextual layers will happen as we combine collections – you can’t do it within one single institution, because then you have only one perspective on a topic. This is happening on a national and European level, and both with content and metadata exchange such as a semantic web approach and Linked Open Data. Metadata is rich if it’s elaborate, and meaningful if it contextualizes, if it presents an object in a variety of historical or topical contexts.

Europeana Connect, for instance, specifies Europeana’s standard data model for harvesting all the data available on the platform. A project like EUScreen must implement this data model to be harvested by Europeana. On a national level major Dutch heritage institutions, such as Sound and Vision and the Dutch Royal Library, are collaborating on a research project called CATCHPlus to implement an interoperable infrastructure for metadata harvesting and exchange (based on OAI-PMH).

And of course we can also now benefit from all the different points of view that were historically kept out of institutions. If we can give contextualized access to our archive, then we can also get more information in return about the items we hold, and this can be extremely valuable. A great example of added value that is being produced outside of heritage institutions is, for instance, the knowledge gathered on Wikipedia.

One thing hasn’t changed: we still hold a great value in historical perspectives, with the information and beauty that lies within the vault, and our expert knowledge about our collections. But to get people really interested, to reach your potential audience, you have to be where they consume material, and provide access to the material in a networked fashion.

Tell me about some of the projects Images for the Future is involved in.

One project is the Open Images Platform, an open media platform that offers online access to audiovisual archival material from various sources to stimulate creative reuse. Footage from audiovisual collections can be downloaded and remixed into new works. Users also have the opportunity to add their own material to the Open Images to expand the collection. Open Images provides an API, making it easy to develop mash-ups. The platform currently offers access to over 750 items from the Sound and Vision archives, notably from the newsreel collection. To allow users to reuse the material, we grant Creative Commons licenses to material we own copyright to, though this is only a fraction of our total collection. Sadly we can’t make the decision to open up material for other copyright holders, but we hope to show them the advantages of it and persuade them to join in building an Audiovisual Commons.

We’re also looking at how mobile phone applications can offer contextual information at certain locations. Our first pilot testing this concept focuses on war monuments. So if people visit one, they can access material from us, Nationaal Archief, and EYE that provides information on its meaning and events related to it. They can also view historical footage of the monument’s site.

Another objective is to revise our current catalog by using speech recognition, image recognition, and crowd-sourced metadata. Currently the catalog only gives the title and basic descriptions at an item level, such as an entire episode, a movie, or a reel of amateur film footage. But broadcast professionals and documentary filmmakers typically look for imagery of a certain event or item or location not listed in the description. People have to review a lot of material they only have a hunch they’re interested in. To fix this, we’re trying to create detailed metadata listed in relation to the video’s timeline, so people who say, “I want imagery of a cow in the 1960s,” get only those clips.

For instance we created a pilot project of a crowd-sourced video labeling game called Waisda? (which translates to “What’s That?”) that asked people to describe the archive’s material with keywords in relation to the timeline. We’re also collaborating with several National Technical Universities to explore how automated speech and image recognition can transcribe material, for instance, to identify a boat. The downside is you have to first train computers and then review the results for accuracy. Computers can transcribe news anchor voices with great precision because they have a standard way of pronouncing – it’s very clear and no background noise. But everyday recordings contain a lot of noise; people make mistakes and mumble. None of these techniques are perfect yet, but if you combine them, we hope to extract a lot of meaningful information in the future.

One of our goals, finally, is to disseminate the knowledge and expertise we gather from these services we’re developing, for instance on our Research Blog. A lot of the technology is open source, so people can implement and build upon the projects themselves.

It all sounds like an innovative, useful public service. So what could be a possible pitfall to prevent countries around the world from doing this?

As with many cultural heritage institutions, we are responsible for generating income, for example through commercial services. This a welcome addition to the base-funding provided by the government. The success of these services relies on charging for the small part of the collections for which we own the rights, but on the other hand we also want to make as much material freely available as possible. So there’s a clash of interests, the archive dilemma.

Images for the Future received substantial but one-time funding. And with the current political environment, we probably won’t receive a similar grant in a near future. In the original project proposal, one of the arguments for digitization was that it would cut maintenance costs. But at the scale we are operating on now, this isn’t the case at all. Now that we have big petabyte robots working for us, not regular hard drives that grow more inexpensive by the second, it’s hugely expensive. Digitizing is only the first step; managing all the digital materials for into the future will be another costly project in itself.