Author: Dwi Aini Bestari (a.dwiainibestari@students.uu.nl)

In INC’s Theory on Demand publication titled “Playful Mapping in Digital Age”, the notions of play and mapping are comprehensively described through various case studies and approaches; geography, game studies, new media studies, etc. One of the cases explained in the book is The Go Go Gozo, a collaborative field course that has been undertaken annually from 2012 in Gozo Island, Malta. This year on May 2nd to 12th, I had the chance to participate in this project and experienced the so-called Playful Mapping and Research; terms that once were vague and new to me. At first, I wondered what Play is; is Play similar to Game? Does mapping refer to the actual cartography or the practice of using Maps like the way I do when traveling overseas or playing Pokemon Go?

In this context, Sybille Lammes and Chris Perkins (2017) define play as an involvement in activities that give participants pleasure, but they also point out that Play is not necessarily unserious and tied to the playground or computer games. They refer to Playful Mapping as mapping practices where participants encounter a combination of pleasure and ludic involvement during the process of mapping that might include map-making, deploying strategic task or navigating (16). Alongside a structured research process through which we encountered theories, methods, design and data, we also got to experience a real mapping field on Gozo Island, Malta. Just as the spirit of the project, ‘Playful’, we were challenged to think creatively about research, understanding mapping as a set of playful activities and embracing messiness and failure of technology.

Tourism and Social Media

Consisting of people from interdisciplinary backgrounds, my group analyzed the role of social media in the making of tourism places on Gozo. Tourism itself has been commonly discussed in various fields such as Geography, Anthropology, Business, Ecology, and New Media Studies. Nowadays, tourism activities are very much linked to social media practices (Bødker & Browning, 2013). As tourism is argued to be inherently social (Pearce, 2005), tourism consists of places that are constructed from social relations (Bødker & Browning, 2013). In this sense, constant connectivity to the internet and social media contribute to tourists’ experiences in making sense of places during the pre-visit, visit and post-visit activities (Ooi & Munar, 2013). However, despite the opportunities of interactivity and user generated content, several issues are addressed that arise from the use of social media in tourism activities.

First, Bødker & Browning (2013) point at how social media platforms for tourism heavily focus on consumption. This is further shown by Szilvia Gyimóthy (2013) who argues that social media’s significance grows bigger as these platforms and activities continuously shape the way people consume tourism offerings. Another implication of social media and mainstreaming tourism information lies on the issue of spatial and social inequality (Navarrete, 2012). New media scholar Christian Fuchs (2012) argues that algorithmic mechanisms of informational flows on the internet creates a bias. In relations to tourism, it is both urgent and interesting to see how information posted on social media reflects mobility patterns that might lead to social and spatial inequality in many areas on Gozo Island; considering the island’s current growth in infrastructure and visitor numbers.

Beyond Social Media: Playing in the Field

Examining the role of social media and socio-spatial inequalities of tourism sites has been commonly done using geo-tagged analysis of social media contents such as photos from Flickr or Instagram. However, generating quantitative data like geo-tagged photos has its limitations. What do the geo-tagged photos exactly say? What happened to other stories that are not posted? This is where the playful methods play a role. As mentioned earlier, the notion of ‘Play’ in this project emphasizes creative thinking; which means opening up to new ideas from different approaches and surprises encountered through the intersection of technology, humans and spaces. These encounters implicated the way we decided our focus, questions and methods.

For instance, to overcome the limitations of specific methods, my group, consisting of diverse backgrounds such as New Media studies, Geography and Earth System, combined different approaches to understand such phenomenon. Besides collecting data from geo-tagged photos on Instagram taken on Gozo Island, we used the qualitative approaches of auto-ethnography and interview. We tried to look at the phenomenon from every possible angle. We were inspired by an urban studies research conducted by Janet Vertesi (2008) about people’s understanding of urban spaces in London. Vertesi (2008) uses cognitive mapping as one of the methods used to get a sense of image of the city where she asked residents to draw a map of London.

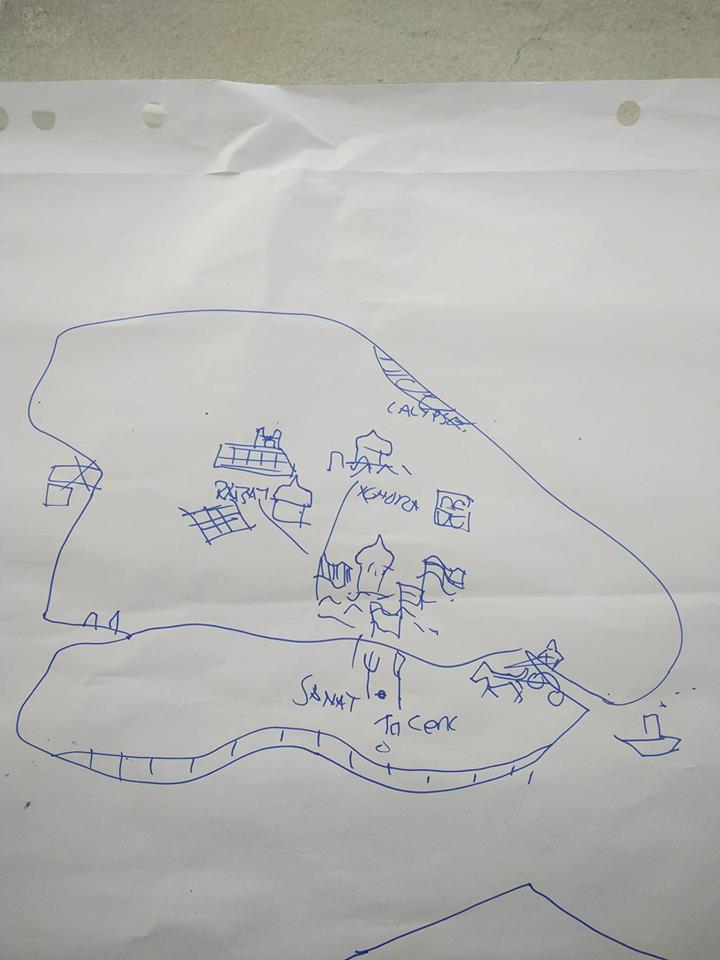

Applying the same method, we started the interview by asking tourists to draw a map of Gozo. This produces not only unique visualizations that represent Gozo through the eyes of tourists but also grasping patterns of tourists’ experiences as well as the stories behind their mobilities. Closely analyzing the drawings, we found similar patterns in what the tourists shared through their drawings. There were five places that were consistently present on the drawings: Mgarr, Xlendi, Victoria, Dwerja and Ramla. Interestingly, the presence of these five places from the drawings supported the same findings from analysis of the geo-tagged photos taken on Gozo Island that were posted on Instagram. From the interview with the tourists, they admitted that they had looked up information about these places on social media such as Instagram and Tripadvisior.

In fact, our direction and perspectives in the research were very much influenced by our playful encounters with the space and people. For example, we performed a situation game through a mobile app that accentuated the notions of unlearning; deconstructing certainties and re-encountering the spaces. During the game, one of the activities was ‘reimagine a place’. In relation to our theme of tourism, we were asked to go to a touristic spot, check the hashtagged photos taken at that place and reenact the photos from a different point of view. We found the ‘ugly aspects’ of tourism site that were concealed in the photos posted on Instagram. Before, we kept our focus on what was present and visible in social media and people’s drawings. Only after this game, we came to realize that we had to also consider absence instead of only looking at presence. Our findings imply how touristic places on Gozo Island are concentrated to only several areas. Filtered and framed information from social media show a link to the ‘missing places’ of Gozo Island from both tourists’ drawings and geotagged photos on Instagram. This link, we argue, creates a loop that repeats itself in touristic experiences and making places on Gozo Island.

‘Playing’ with Research

The lesson learned from the projects is how trying different methods and viewing from different angles and approaches could be a very productive and insightful way of research. This allows us not only to critically reflect on the limitations of a method but also creatively think of other possible ways to provide findings that are not only based on validity but also diversity and complexity. Furthermore, playful encounter among humans, technology and places provide a chance to experience the messiness of the field and failure of technology as meaningful part of learning; learning on overcoming boundaries. Now, shall we play more?

Note: The research discussed above was collectively conducted by Adam Doneo, Connor Stile, Dwi Aini Bestari, Lucy Crier and Xuechen Qu under supervision of Sybille Lammes.

References:

Bødker, M., & Browning, D. (2013). Tourism sociabilities and place: Challenges and opportunities for design. International Journal of Design, 7(2).

Manuel-Navarrete, D., & Redclift, M. (2012). Spaces of consumerism and the consumption of space: Tourism and social exclusion in the “Mayan Riviera”. In Consumer Culture in Latin America (pp. 177-193). Palgrave Macmillan US.

Munar, A. M., Gyimóthy, S., & Cai, L. (Eds.). (2013). Tourism social media: Transformations in identity, community and culture. Emerald Group Publishing.

Ooi, C. S., & Munar, A. M. (2013). Digital social construction of a tourist site: Ground Zero. In Tourism Social Media: Transformations in Identity, Community and Culture (pp. 159-175). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Pearce, P. L. (2005). Tourist behaviour: Themes and conceptual schemes. Channel View Publications.

Perkins, C., & Lammes, S. (2017). An Introduction to Playful Mapping in the Digital Age. In C. Wilmott, C. Perkins, S. Lammes, S. Hind, A. Gekker, E. Fraser, & D. Evans, Playful Mapping in The Digital Age (pp. 17-27). Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures.

Vertesi, J. (2008). Mind the gap the london underground map and users’ representations of urban space. Social Studies of Science, 38(1), 7-33.