14/05/2019 – Luca Recano and Sebastian Olma

Sebastian Olma is Professor in “Autonomy in Art, Design & Technology” at “Avans” University of Applied Sciences in Breda and Den Bosch in the Netherlands. He lives in Amsterdam. For years he has been dealing with social and cultural criticism, in particular with regard to the politics of cultural industries. In his book, “In Defence of Serendipity. For a radical politics of innovation “(2016), Sebastian Olma advances a powerful cultural critique against the neoliberal paradigm of innovation, which crushes the possibilities and the differences of social innovation on the incremental scale of technological and economic innovation, and so making the development of innovation in general sterile.

Luca Recano: “In Defence of Serendipity” opens with a preface by Mark Fisher, a brief but dense critique of what he calls “the great digital swindle”. In it, Fisher states that “generalized insecurity [precariousness] leads to sterility and repetition, not to surprise or invention”. Fisher was the protagonist of a profound investigation in the malaise of our age. What do you think when you reread his words today; after he took his life and his writings became a symbol of desperation for those who long for change but are confronted with the absence of alternatives to the present?

Sebastian Olma: I think that what Mark Fisher said in the preface to In Defence of Serendipity still very much applies. Perhaps even more so today than it did when he wrote it. I mean this in the sense that his critique of the Californian Ideology is becoming more and more mainstream now. There is still a lot of propaganda out there celebrating the blessings of smart cities and digital societies and so on, but it has become much more difficult to deny the existence of the brutal extraction economy that such corporate marketing is supposed to mask. When even someone such as Harvard Business School professor Shoshana Zuboff writes a damning critique of “Surveillance Capitalism” and the illicit exploitation of “behavioural surplus” it means that the tide is turning. Mark relentlessly attacked digital propaganda from very early on and he did so from a position of deep fascination for cybernetics and the (pop)culture it spawned. One of the reasons why his 2009 book Capitalist Realism was met with such an enormous resonance was that it revealed the digital pipedream to be part of a reactionary political strategy. This was absolutely crucial for people like myself at the time because it proved that not everyone had lost their mind, not everyone was buying the digital cloud-cuckoo-land that organisations such as TED and O’Reilly Media were pushing on us.

If you ask me, I think this is how we should look at Mark’s intellectual legacy. There is nothing in his writing that would indicate submission to desperation. I’d argue that the opposite is true. There is a radiant intensity in his work that is extremely life affirming, always searching for cracks in a suffocating present; cracks that might lead toward a possible future. This comes across with particular vivacity in his last two books, Ghosts of My Life and The Weird and the Eerie. If one can speak of gloom there, it’s always that of the present that needs to be overcome. So no, I don’t see Mark as a symbol of desperation at all; for me he was and remains a fiercely optimistic thinker who inspired so many people in their belief in and struggle for “a world which could be free” as he puts it in his fragment on Acid Communism.

L.R. In the book there is much emphasis on the role of social movements and counter culture. You live in Amsterdam, a city that was once famous for its innovative squatters movement, and, at the same time, for corporate innovation. In the book, you discuss the American counterculture and its role in the formation of the so-called Californian Ideology. What would you say is the role today’s social movements and countercultures play in terms of the development of capitalism (innovation, creativity etc.). Do you think they have become fully absorbed within the neoliberal paradigm of creative and digital work, as the French sociologists Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiappello seem to argue? Is there still room for autonomy and experimentation in innovation processes and if so, under what conditions?

S.O. You’re right to single out Amsterdam as a city with a certain historical legacy of cultural openness and political progressiveness that in the second half of the 20th century translated into a proliferation of spaces for subcultural experimentation. These spaces formed a network that indeed drove cultural innovation throughout the city, turning it into a beacon of late 20th century urban creativity. Some sociologists have argued that Amsterdam was the European city that gave Richard Florida a kind of blueprint for his idea of the creative city. On the US side the model was San Francisco. So yes, there are definitively a number of similarities between the Dutch and Californian experience with regard to the historical role subcultures played in processes of cultural, and following from that, economic innovation. You’re also right in pointing to the destruction of these drivers of innovation by neoliberal politics. The suffocation of urban space by massive financial speculation and overinvestment in real estate seems to be much worse in San Francisco but is also painfully felt in Amsterdam.

This is a development that goes far beyond the question of subculture. In fact, certain forms of artistic and subcultural practice are often perverse beneficiaries of the neoliberal re-modelling of our cities as they are functionalized as the “creative” veneer of an otherwise homogenized urban fabric. Those who suffer are lower and middle income households but increasingly also the young, small business owners, teachers and even doctors who can’t afford the rising rents anymore. So the problem is not so much (or, at least, not only) the disappearance of subcultural spaces but the de-diversification of urban life. This is what destroys the city as a serendipity machine and makes it increasingly predictable and boring. What’s more, by destroying the serendipitous potential of the city, a society’s capacity to innovate also goes down the drain. Which in today’s situation means the destruction of the possibility of any kind of future. I’m not sure our city planners and political strategists have grasped the gravity of their failure to challenge the current trajectory. Who’s going to stop the neoliberal extraction economy that is causing the sixth mass extinction if not a truly cosmopolitan politics born out of the city’s powers of invention?

L.R. The historical and etymological reconstruction of the concept of serendipity (in short: the process of discovering or finding something useful, valid or good, without specifically looking for it) that you do in the first pages of your book, refers directly to an epistemological and ontological problem: how does the world become, what moves it, how are new realities “produced”? Later in the book, you invoke Gabriel Tarde’s “forgotten” sociology and its usefulness for a social theory of innovation. Why do you think a theory of social innovation is needed today? Why are “good practices” not enough?

S.O. We desperately need a political discussion on social innovation as a way of countering the destructive impact of the neoliberal extraction economy on our cities, societies and, ultimately, on the planet. What is currently staged in the name of social innovation is a farce with the aim of keeping the great challenges of our time unaddressed. Actually it’s quite obvious, if you look at the methodologies on which organizations such as the British Nesta or their smaller Dutch counterparts operate: a “wicked” problem such as, say, world hunger, economic exploitation or environmental destruction is put through a series of steps, reducing it to something that can be solved by an app, a business model or a combination of both. Design thinking is an obvious example of this, but the so-called social innovation community has developed their own versions of this. In my book, I call this the “gymnastics of changeless change”. It’s a little bit like Evgeny Morozov’s “solutionism” only much more cynical. Instead of addressing our complex and often global problems in such a way as to work towards an appropriate response, a symbolic act is performed that doesn’t change anything at all but gives those “solving” the problem the feeling that they are “making the world a better place”. The perfidy of the changeless change variety of social innovation lies in the fact that it wastes the energy of a young generation who are really serious about wanting to change the world for the better; energy we desperately need.

We need a theory of social innovation to help us separate changeless change from real change. The younger generations need to be able to decide what’s worth investing their energies in and what isn’t. Examples of “good” or “best practices” can sometimes be inspiring but if you really want to save the world, you have to understand how our complex social systems work, how emancipatory social change has been brought about historically, and what the powers are that you are up against today. Supporting the new generations in finding their way is a great responsibility. The most deplorable role today is played by those grown up functionaries who know exactly what’s going on but keep on playing the game of changeless change in order to defend their acquired institutional position.

Gabriel Tarde’s work is interesting in this respect. If even a century old sociologist can help us unmask social innovation as changeless change, imagine what kind of innovative thinking we could produce if we taught students once again to think critically about society. By way of consideration, the Anthropocene hypothesis needs an intellectual mobilisation powerful enough to stop the sixth mass extinction.

L.R. Tarde’s theory seems very useful in describing social ontology as the basis for innovation, especially when it comes to the micro dynamics of innovation. But when innovation processes involve society as such, the dynamics of invention-imitation that Tarde postulates for individuals move to communities and complex systems, involving other factors, both structural and contingent. Here things get complicated.

There are social theories, some related to Tarde’s sociology, that address social innovation in all its complexity. Manuel Delanda’s Assemblage Theory, Bruno Latour’s Actor-Network Theory or theories of complexity come to mind. Furthermore, critical theory, Marxist and feminist radical theories and in particular the theory of political ecology and that of social reproduction provide us with a framework to understand the relations of power and domination and the social relations of production in new ways. They attempt to open the problematically universalist view on humanity to include relations to non-human, natural and technical entities. Thinkers like Bernard Stiegler and Yuk Hui develop new theoretical tools by opening up new paths of philosophical and “cosmotechnical” thinking with regard to the challenges of our age, beyond the paradigm of the Anthropocene.

Do you think using these theories to reconstruct a critical approach to innovation is useful, clarifying the contradictions, conflicts and possibilities that it entails, and frame it in the light of the challenges of ecological and social change of contemporaneity?

S.O. Are you referring to your own approach here? I’m not sure it matters so much what your theoretical resources or references are as long as you don’t use them for purposes of academic mystification. Take something such as actor network theory. Career academics have a weakness for it because it provides them with a million complex sounding ways of saying “there are relations”. This works towards successfully getting research grants because it allows one to adapt to the latest policy fashion and write dozens of vacuous papers. Unfortunately, it is less effective to address the challenges we are facing. Which is exactly why Bruno Latour, the intellectual architect of this approach, returns to a surprisingly radical political analysis in his consideration of the Anthropocene. According to him, a powerful elite understands extremely well that the neoliberal extraction economy is, at the very least, going to cost the lives of billions of people. However, they have decided that it’s worth it. These are not people one can challenge by building an app or tweaking a mobile phone into a more sustainable product. It’s going to require gargantuan political effort to deprive them of their power. If your theory or analysis is going to be helpful to build momentum that could lead to such an effort, then you’re on the right path. However, in order to do this, you need to say much more than “there are relations”. Some relations are more powerful than others and we need social theory that helps us understand how to confront those.

You are right to point to Bernard Stiegler as one of the great philosophers of our time. Unfortunately, he isn’t widely read – something for which his convoluted writing style carries at least part of the responsibility. Don’t get me wrong, no one understands technology and its role in social change processes better than Stiegler. It just seems that the world has un-learned to engage with this kind of defiantly complex thought…

L.R. Throughout your book, you refer to Bernard Stiegler’s notion of technology as pharmakon, i.e., its ambivalent potential to be poison and/or cure. The public discourse on the relationship between technology and social change reflects this ambivalence: there are enthusiastic techno-utopians and doom-mongering dystopians; techno-determinists techno-neutralists and so on. It’s quite a confusing picture. What is the antidote to this confusion? Is it possible, to paraphrase Donna Haraway, “to stay with the trouble”, and to be involved in today’s world of technology while at the same time designing a different techno-social paradigm, or at least working toward it?

S.O. I don’t really see any reason for confusion. Take the philosophy of Bernard Stiegler that you’re referring to. Technology has always been part of human development and, as Stiegler argues, can even be seen as that which defines the human life form. So, of course it can be either good or bad. That’s true for a stone wedge as much as for a computer. In this case you’re right, techno-determinism is mental. However, I would take issue with the picture you’re painting here. There is no balance at all between techno-euphoria and doom mongering. The last two decades have been dominated by the idea that digital technology in its current use is necessarily beneficial to society. Take social media. We were so euphoric about its supposedly positive effects that we have more or less forced social media onto the fragile psyches of our youngsters without even the slightest cautionary warning or preparation. You can compare this to parents giving their 16-year olds cocaine because “it makes them think faster”. I’m not playing the fool here. The addictive impact of social media has been programmed by the industry down to each and every micro-dopamine boost. Ten year’s later, the first longitudinal studies are coming out, clearly documenting the harm that’s been done. We’re pulling our hair out in despair because of the seriousness of this form of addiction.

By contrast, I haven’t seen anyone who’s argued that the invention of the computer signals the inevitable end of the world. There might be some nutcases out there, but they have nowhere near the visibility that the digital evangelists have. If you want to know why this is the case, you only have to read aforementioned Harvard Business scholar Shoshana Zuboff who meticulously documents the enormous resources and strategies employed by the IT-industry in order to influence policy making and public opinion in their favour.

So, this is the anti-dote to the situation you’re describing. Calling out these strategies and understanding that there is nothing natural or neutral about the technological trajectory but that it follows political and economic interests. If we want tech that makes our lives better and helps us save the planet, we need to create the political conditions that force it into doing so. This is no enigma, but again requires enormous political effort.

L.R. Despite the neoliberal hegemony, spaces of resistance and experimentation still exist. There are self-organized communities linked to the hacker and maker culture (hacker spaces, hack labs, critical maker spaces); initiatives around “the commons” (P2P, free software, free hardware, open access); platform cooperatives; IT unions and new forms of organized labour; activism against war, exploitation and the invasion of privacy; initiatives for progressive policies such as basic income (involving activists, designers, entrepreneurs and politicians). What do you make of these different movements? Is it possible to frame them in terms of an ecosystem of alternative possibility in the context of the global ecological and social crisis? Is it possible to construct a common discourse and a political practice among these experiences?

S.O. I’m not sure. Some of your examples here are pretty straightforward. Forms of organized labour for precarious workers? Of course. Anti-war, pro-privacy, feminist activism? Absolutely. For the rest, it all depends on what it is these different movements and initiatives are after. Are they seriously interested in developing practices that could help us build a desirable future? Or are they merely trying to carve out a comfortable niche for themselves in the existing system? For those who want to seriously build a future, they have to be extremely careful and (self)critical when it comes to deciding what works and what doesn’t. What we see at the moment, particularly in The Netherlands and Belgium, is a very unfortunate attempt to resuscitate the nineties zombie-idea “small is beautiful”. In the name of “the commons” or, even worse, “commonism” [sic] good initiatives (in line with those you’re describing) are lumped together with the most revolting neoliberal projects in order to generate a map showing that in fact, the new society (of the commons) is already here. Everything is fine, we’re saved, thank you very much! The logic here is: these are not big organizations so they must be part of the commons. At a slight of hand, economic precarity and political weakness become the aspirational parameters of the future. Is there a more appalling way of throwing the new generation under the neoliberal bus?

I’m not convinced by the hypothesis of the commons precisely because its real political effect has thus far been extremely problematic. Celebrating a potentially emerging infrastructure of a future commons has done nothing to prevent the ongoing destruction of the actually existing infrastructure of the public. I’m referring to the ruthless privatisation, outsourcing and commercialisation of our public services from health care and housing to government itself. The brilliant work of economist Mariana Mazzucato has done a lot to uncover the obliteration of public value that the religious belief in the superiority of the market is causing there. I mean, I’m all for dreaming about a future commons but isn’t it more pressing to stop the sell-out of the public first? As long as the proponents of the commons turn their back on this outrage, they don’t deserve to be taken seriously. If the idea of the commons is overwhelmingly employed to sustain careers, initiatives, research and policies that defend the neoliberal status quo, it clearly doesn’t belong to what you call “the ecosystem of alternative possibility”!

L.R. In your book there is a fairly explicit criticism of organizations like Nesta and its director Geoff Mulgan, for the role they play in the field of digital social innovation. These organizations are central in defining EU policies with regard to the use of digital technologies in the industrial, logistic sector and urban development (smart cities). It seems to me that the EU is trying to find a position that is different from both, the ultra-capitalist and neoliberal model of Silicon Valley and the statist and centralist model represented by China. What role can social innovation play in this context? Is this more than rhetoric and marketing? Do you think the EU has learned from the way its creative industries and digital economy programmes have aided the gentrification of our cities and the precarization of labour, and masked the further financialization of the economy?

S.O. It’s absolutely fascinating to see that the very same people who were responsible for the creative industries paradigm are now at the helm of the digital social innovation agenda. Let’s have a quick look at the creative industry paradigm. The basic idea was to create a set of policies that proactively intervene in the structural transformation of the economy (very broadly: from industrial to post-industrial) by infusing it with the power of creativity (read: art and design). Creative industries “thought leaders” like Geoff Mulgan and Charles Leadbeater were very close to Tony Blair whose Third Way politics implemented neoliberalism in Britain in the sense of the market becoming the central principle of government. Like Blair, they were in favour of abandoning the European approach of social democratic policies, including more democratic forms of economic governance. Instead, they looked at the US in search of a new industrial model. The most effective path toward a creative economy our “thought leaders” believed to have found in the business models of Silicon Valley.

However, the power of the American ICT-industry had grown out of specific historical conditions, was backed by massive government funding and, increasingly, protected by a powerful apparatus of corporate laws and regulations. So, what happened was that the European creative industries discourse became a rhetorical shell that imported Silicon Valley’s corporate culture – the famous Californian Ideology – into Europa without having an industry that could profit from it. The creative industries were supposed to grow basically by building cultural and creative clusters in our cities and infusing them with West-Coast entrepreneurial zest. Obviously, I’m simplifying somewhat. However, instead of becoming the engines of a newly emerging creative economy, these clusters became the creative bulldozers of the real estate machine that is now vandalizing our cities. Clearly, the industrial strategy failed. Despite this failure, the EU and national governments continued to push the ideological dimension of the creative industries agenda, effectively implementing a Californian re-education programme for Europe’s cultural and educational sectors: artists (and citizens in general) needed to reinvent themselves as entrepreneurs, collective creativity made way for individualistic competition, social values were declared null and void unless they generated a price on the market. Obviously, none of this helped European economies to become more competitive. Instead, it laid waste to a cultural sphere that could have generated an effective European defence against and response to the Silicon Valley extraction economy. While it would be nonsense to blame the creative industries agenda alone for the suffocation of our cities or the degeneration of our political culture, it has definitively been an enabling factor.

Are we really supposed to trust armchair strategists, who are responsible for this absolute disaster because they have the cheek to refashion themselves now as digital social innovators? Who approach emancipatory politics as if it was a question of launching a series of digital start-ups? You must be joking. There are serious scholars and activists who think about emancipative forms of utilising digital technology. Morozov has just published a luminous intervention on what he calls “digital socialism” in New Left Review. Let’s pay attention to them, not to irresponsible consultant types who cling to a failed approach.

L.R. You regularly challenge and criticize prestigious cultural institutions in you hometown Amsterdam for their complicity in gentrification processes or for uncritically promoting ideological tropes like smart city or sharing economy. Yet many of these institutions are quite ambiguous in their nature: their opportunism is interlaced with an imaginary of radical or progressive social transformation: ecological transition, social justice, global citizenship, commons, civil rights. Amsterdam’s cultural institutions, of course, are no exception in this. Is it possible to intervene in these contradictions, “hacking” these institutions so they become more autonomous and regain some political utility?

S.O. I think this depends on each institution’s individual level of corruption. Many of them were set up explicitly as infrastructural support of the creative industries paradigm. You can compare them to the Stalinist “culture palaces” of the former Eastern bloc. They exist for one purpose only; to streamline civil society according to the needs of neoliberalism. Their message to the new generation is that politics has become obsolete. Celebrate your individual identity, believe in technology, optimize yourself for a life of constant competition, that’s all you need to do to make the world a better place.

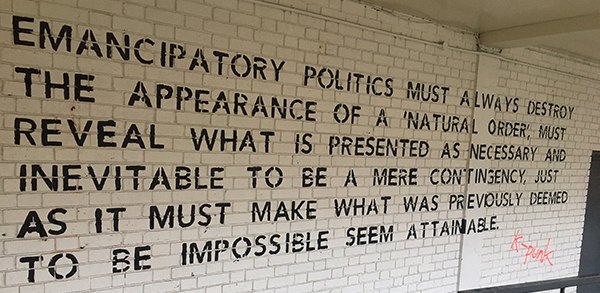

In other words, – and here we return to the beginning of our conversation – they contaminate us with the toxicity of capitalist realism, i.e., spreading the lie that it is neither possible nor necessary to change the rules of the neoliberal game. The fact of the matter is that we can and urgently have to change these rules if we want humanity to survive. It’s called emancipative politics. It’s what neoliberals fear more than anything else. There are many ways in which cultural institutions can contribute to the construction of such a politics, from raising awareness of the debilitating psychic effects of precarity and permanent competition on the individual level to building collective agency against the continuing vandalising of the city by the rich and powerful. If that’s what you mean by hacking, then yes, let’s hack away!