By Ruben Brave

On October 10/11 2019 I presented our applied science project Make Media Great Again (MMGA) at the Post-Truth Society from Fake News, Datafication and Mass Surveillance to the Death of Trust conference on Malta; an initiative of new media teacher of the University of Malta and founding Director of the Commonwealth Centre for Connected Learning, Alec Grech. The Post-Truth conference included speakers from The Economist, Worldbank and Google.

In my talk I not only summarized how participatory journalism can be a cost-effective and inclusive solution for quality control in online publishing but also indicated how MMGA’s curated process leads to reciprocity and reflection.

The atmosphere on the Malta conference seemed a starting point for higher awareness and consciousness of the roles and responsibility all agents have on the internet when it concerns mis- or disinformation, the two pillars of fake news.

The very real impact of fake news on people lives was evident by at least two situations at the Post-Truth event. First a kaleidoscopic situation occurred when speaker and Iranian blogging pioneer who was imprisoned for 6 years, Hossein Derakhshan, held his talk named “Post-Enlightenment and the Personalization of Public Truths”; he was publically verbally attacked from the audience by co-speaker Maral Karimi who claimed that Derakhshan himself was guilty of spreading fake news that had supported people getting incarcerated or even worse.

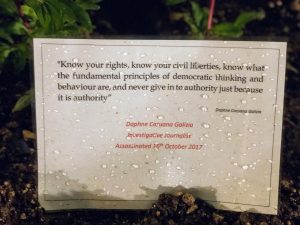

Also, a moderator (and journalist) was under police surveillance during the event as he/she had key information concerning the offender(s) on the murdered Maltese Panama-papers journalist, Daphne Caruana Galizia; a societal disruptive case due to the various investigations with an abundance of dubious reporting to the public. The social indignation concerning the handling of the Galizia case erupted at several unexpected moments on the event.

Fake news leads to real problems and is tied to social injustice. What can we do as citizens? Read my media-enriched talk below:

Public Rebuttal, Reflection and Responsibility – An Inconvenient Answer to Fake News

I’m co-founder of Make Media Great Again [3], shortened called MMGA, a Dutch non-profit initiative [4] focussed on providing a possible part of the solution concerning fake news. A Dutch project with an (according to some people) funny name [5] but with a serious mission.

What do we do at MMGA? Collaborating with publishers and community to fight misinformation. We improve the quality of media together with their pool of involved readers, viewers and listeners. We have built a transparent system for actionable suggestions and specific remarks from this community pool. NU.nl (translated as NOW.nl) with 7 to 8 million visitors a month and by far the most important news service in the Netherlands is our test partner [6]. We test with a group of critical and knowledgable NU.nl readers (called ‘annotators’) [7] who offer suggestions to increase the journalistic quality through the balanced use of sources and clearer transfer of information.

And when I talk to my American friends [8] about Make Media Great Again they all agree what a great potential our endeavour has. But also they echo their main remark:

Change the name, change the name, change the name.

And to be fully honest to a large extent I must agree with this. Because for some reason, we keep getting enthusiastic emails with subjects such as: “Yeah let’s build that wall!” [9]

But nonetheless, we are not changing the name, not yet…

My personal realization for the need for MMGA started when I was confronted with “fake news” on the publicly funded national NOS website, the Dutch Broadcasting Foundation. For some of us, it might not be a surprise that a state-funded medium spreads wrong information but in the Netherlands people still put a lot of trust in them.

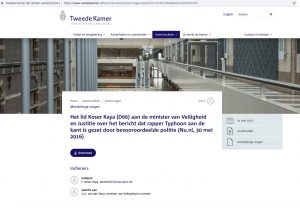

The case was quite remarkable. During election period the website reported that the frontman of the Labour party was asking questions in Parliament about ethnic profiling by the Dutch police. [11]

figure 1: example of misinformation on the website of the national Dutch Broadcasting Foundation concerning a political party asking Parliamentary questions concerning ethnic profiling by the Police in the Netherlands

After investigating the Parliament website and ultimately asking the Registry what these questions actually were, I got an email that the Labour Party did not at all had asked questions about ethnic profiling. It seemed that a female member of Parliament of the Democratic Party with a migration background had asked the relevant questions.

figure 2: update on Dutch Parliament website concerning the party and person that did ask questions concerning ethnic profiling by the Police in the Netherlands

This information could have impacted voting behaviour, at least it influenced mine. When I confronted the Dutch Broadcasting Foundation and asked if they would at least consider editing the headline of the concerning article the editor-in-chief responded agitated with the remark: “I’m not going to contribute to history falsification!”

How curious…

And how can anyone tell these days what is factually accurate and what isn’t? What is formulated to reveal and what is written to conceal or even to mislead? These are increasingly pressing questions, especially as a new historical round of disinformation is upon us and ‘fake news’ is flourishing in all its glory. Could critical readers help in improving the reliability of “our information”?

Our society would benefit from better news. Yet we don’t have the tools to improve this ourselves. This has changed with our open-source movement MMGA as we offer transparent tools for journalistic reporting. Where everyone can contribute and we invite everyone to join our cause. For a clearer world.

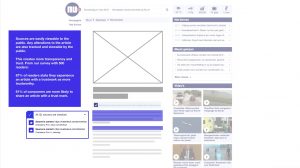

Up to 50,000 readers were involved in our first pilot, with candidates individually selected from the news organization’s readers’ commentary panel (their forum NUJij). From these readers, more than 300 are now registered as an annotator.

figure 3: screening, selection and training process overview

And from this group, we selected, screened, and trained knowledgeable and/or critical thinking readers to actually work on annotation assignments.

How we do it? Improving the quality of media through annotations? Well, we believe people have unique, diverse views and also relevant knowledge that helps the editorial process and quality. With our digital tools, people are able to detect misinformation, biased language and false contextualization. MMGA annotations are practicable suggestions, labelled notes, directly attributed to words, sentences or paragraphs. They are actionable for the editor, avoid debate based on personal preferences and, if correct, directly trigger a correction within articles.

Editors are free to implement or not. Because the annotations are immediately executable and based on the principle of journalistic objectivity, they overcome the known issue of lengthy debate due to subjectivity that arises with regular reader comments. The system differs from the well-known response form, whereby the reaction usually concerns disagreement with the online paper’s opinion or the tenor of the whole article. Annotations focus on specific elements of an article and are structured according to annotation labels. Our tests not only were to test the annotation system itself but also see how those involved respond to and work with it.

Furthermore, provided these annotations are clear, factually accurate and presented with proper transparency, they provide the necessary motivation for their immediate implementation, given that doing so will only improve the quality of the work in question.

Why we do it? To improve the credibility of media and strengthen the bond with their audience. The credibility of the media is being questioned more and more, whereas the media are seen as the first party to protect us from wrong information. This fundamental role of media is essential to enable proper functioning of democracy and constructive social debate, thus fortify social cohesion.

The potential of this idea goes beyond journalism; in fact, any organization or body that provides information as a ‘public service’ could benefit from it, be they governmental institutions or museums. And it is arguably becoming increasingly important to use the openness of the internet to facilitate the representation and participation of diverse and hitherto underrepresented groups in media and society at large.

Editorships, newsrooms and the army of opinion leaders typically reveal a skewed distribution in their composition with respect to gender and place of origin and residence, among other things. Whereas MMGA, with its “diversity panels” geared towards the nuanced use of language in journalism and its emphasis on multiple perspectives in reporting, holds the possibility of genuine balance. True quality is arguably impossible without diversity. We find it important that our group of annotators is as diverse as possible. Men, women, people from various ethnic backgrounds and minorities of all sorts. This minimises the chance of overlooking particular contexts. A more diverse group can, according to scientific research ([12] see pages, 21, 31 and 38), improve the quality of news offerings and build trust in the sources of these offerings. Trust, in particular, is now one of the major issues in mainstream journalism. The study that yielded the findings involved globally recognized names such as the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, the BBC and, last but not least, The Guardian. We, therefore, invite anyone who shares our concerns and wants to help to contact us [13].

MMGA sees diversity as a means of improving the quality of published content, rather than an end in itself.

The fact that media organizations themselves are beginning to admit the need to fight fake news to maintain their readership’s trust opens the door for collaborations. And this is how we hope to work, too. After all, the idea isn’t to destroy existing organizations but to improve the quality of what they produce.

So there you have it! MMGA is cost-effective (because we mainly work with volunteers) and a value-added layer of contributors who create a safety net against misinformation, thus giving the hardcore fake news no change. We collaborate with universities, well-known investigative journalists and impactful media for a maximum reach [14]. Solution found it’s even politically correct because it’s all-inclusive… Yep, case closed… Couldn’t anybody else come up with this? Oh well. No problem, we got it covered…

At least… we thought. Before the post-truth reality punched me in the face!

It happened to me when I was vigorously watching a new tv series: The Man in the High Castle [15].

Figure 4: poster tv-series Man in the High Castle

An American alternate history television series [16] depicting a parallel universe where the Axis powers (Rome–Berlin–Tokyo-axis) win World War II – so the Nazis and their partners won instead of the Allies. It is produced by Amazon Studios and based on Philip K. Dick‘s 1962 science fiction novel of the same name [17]. Dick is popularly known as the writer of the books behind movies as Blade Runner and Minority report.

Side-note: As Ta-Nehisi Paul Coates, national correspondent for The Atlantic, states that for a lot of African-Americans the world Philips K Dick sketches has a lot of resemblance with their actual reality. But also other more general ethical questions Western society currently has in “our reality” are addressed.

So back to me and the series. During the period I’m binge-watching the series I’m using Facebook and there – for some reason – I’m directed to a journalistic looking Facebook-post with the purport that Bill and Melinda Gates are not trying to save the world from malaria or polio but instead actually are testing experimental medicines (on behalf of large pharmaceutical companies) on poor Indian kids…just like the Nazi’s would do!

And I must be honest, for a second I felt the rage and indignation coming up inside of me. This was big news! The world needed to know about this. And I was ready as ever to share this post with my friends and relatives. To shine the light on this wrongdoing and work to a clearer world.

But then I remembered MMGA’s code of conduct, inspired by the journalistic ethical code the Bordeaux Declaration, multiple Dutch guidelines concerning journalism and prevention of improper influencing by conflicts of interest and last but not least the Five Pillars of Wikipedia. Our first directive states:

“Your annotations are based on facts for which you can indicate a reliable source (which thus are verifiable and can be held accountable), as completely as possible and regardless of the opinions expressed about this source.”

I couldn’t even find one reliable source backing up the claims made in the Facebook-post. Thus even so how much I felt I was obliged to spread this “news” I also did not want to have the responsibility for an unverifiable article.

And this reminded me of the results of one of the first MMGA tests we conducted concerning our Trustmark on 500 random internet users. The Trustmark signifies and guarantees that all articles are under audit of an independent community, sources are easily viewable to the public and any alterations to the article are also tracked and viewable by the public.

figure 5: test results adoption indication MMGA Trustmark

To create more transparency and trust. From our survey with these 500 readers, nine out of ten stated they experience an article with a Trustmark as more trustworthy. Also, more than 6 out of ten were likely to share an article with a trust mark.

figure 6: overall function MMGA Trustmark

So what will happen when people become more aware when such trustmarks are missing in the article they are reading? Would they be more conscious when they are sharing unmarked articles?

Without the network effects of the Internet wrong information would probably have the same damaging effects as simple “false gossip” in the contained context of let’s say a school class. We are keen to look at platforms such as Facebook and news media like the Dutch Broadcasting Foundation as guilty parties for the fake news problem. And reach for all kinds of tech-related solutions to save us.

But based on my own Man in the High Castle experience I suspect we still need to make a leap in our societal consciousness if we are going to survive this post-truth era:

“We are not merely using the technical infrastructure of the internet, as if it is something outside of us. Beyond our own power and responsibility. We are an integral and decisive part, the living nodes, of this global information network.”

figure 7: Quote of Daphne Caruana Galizia at the protest memorial in Valetta on the night before the conference

And therefore the name of our organisation stays as it is. To remind us of the easily overlooked fact, another inconvenient truth, that we all individually have to play our part – as reflective and responsible citizens – to make media great again.

Figure 8: MMGA co-founder Ruben Brave being interviewed at the post-truth conference “From Fake News, Datafication and Mass Surveillance to the Death of Trust” held 10-11 October 2019 in Valetta on Malta. Copyright photo’s by Harry Anthony Patrinos, Practice Manager World Bank for Europe’s and Central Asia’s education global practice.