Last month INC proudly published Sepp Eckenhaussen’s Scenes of Independence: Cultural Ruptures in Zagreb (1991-2019) as the third edition of the Deep Pockets series. It tells the story of ‘independent culture’ in Zagreb in a way that is both theoretical, practical, and personal. Below you can read an excerpt. To get a free download or order a print-on-demand copy of the full book, please visit the publication page.

Zagreb, Rebecca West says, ‘has the endearing characteristic, noticeable in many French towns, of remaining a small town when it is in fact quite large’. She wrote these words in the late 1930s, when Zagreb had just over two hundred thousand inhabitants. By 2019, this number has almost quadrupled. Yet a similar feeling captures me while roaming the city today. It seems like Zagreb is a capital and a village at the same time. It is almost impossible to get lost in the streets, squares and parks squeezed between Mount Medvenica and the Sava River.

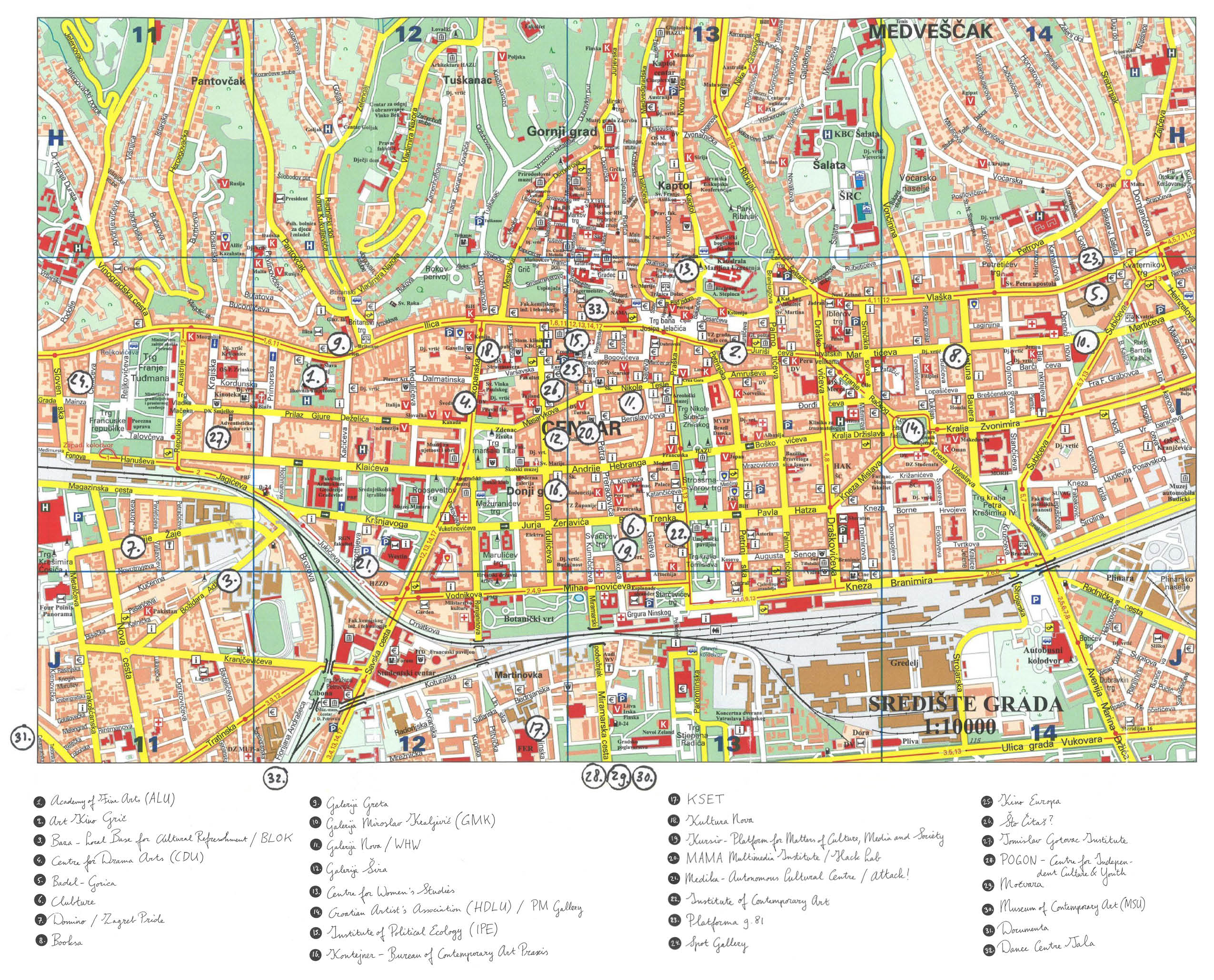

Zagreb – between Sava and Medvenica.

According to West, Zagreb’s village-like character is ‘a lovely spiritual victory over urbanization’. A dubious compliment. Within a few years after West’s visit, two hundred thousand refugees of World War II settled in the city, affirming that in Zagreb, too, the force of urbanization is more than capable of bending the laws of spiritual life. It could hardly be said that West was naïve, though. Her Black Lamb and Grey Falcon: A Journey Through Yugoslavia is widely regarded as one of the greatest – some say the most foreseeing – books ever written about Yugoslavia. It describes with great finesse and pointy humor the life of the Balkan peoples during centuries of hardships and the constant political quarrels amongst Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, Bosniaks, Albanians, and Macedonians. If anything, West’s spiritualist interpretation of life in Zagreb hints to the understanding that this city is not so easily readable.

The Britanski Trg market on an average weekday.

Zagreb is a fragmented city; its many neighborhoods seem to be different worlds. Even the city center, which is not very vast, is split up into three parts: one for politics, one for religion, and one for life. The old city, located on a hill and called Gornji Grad (upper town), is the seat of the Croatian government. From here, the county’s rulers have a wide view over the rest of the city and the Pannonian Basin beyond it. Over the past decades, Gornji Grad’s old age and altitude have also made it into a well-visited tourist attraction. As a result, a visitor of Gornji Grad will encounter the strange mix of formal power and touristic entertainment usually reserved for royal palaces. On the slope of the hill stands Zagreb’s magnificent cathedral with its towers in eternal scaffolds, surrounded by the clerical complexes. This is Kaptol. Together Gornji Grad and Kaptol are the epicenter of Croatian political and clerical power, which are deeply intertwined.

A view from Gornji Grad.

At the foot of the hill, Donji Grad (lower town) begins. This part of the city, built in the nineteenth century, is surrounded by Gornji Grad on the north and the Green Horseshoe on all other sides. The Green Horseshoe consists of three boulevards modeled after the Ringstraße in Vienna. Its main elements are leafy parks, botanical gardens, and neo-renaissance pavilions designed to simultaneously impress and relax flaneurs and other passers-by. In Donji Grad, one can find the main shopping street Ilica, restaurants, hotels, a handful of one-room cinemas, the botanical gardens, the train station, and the main square Trg Ban Jelačić – usually simply called Trg. It is here that public everyday life takes place. The fact that Zagreb’s urban life is this concentrated is quite joyful. Hardly a day passes without a random encounter with a friend or colleague.

The equestrian statue of Ban Jelačić.

A few kilometres to the East of the city centre, one finds the green pearl of Zagreb: Maksimir Park. The huge park contains five basins full of turtles, a small zoo, a restaurant pavilion overlooking the tops of the trees, and enough lush green and small pathways to wander around for a full day. No wonder young families, dog-walkers, sunbathers and tourists flock the park whenever the sun comes out. It was built by Zagreb’s bishops in the late 18th century and was the first large public park in South-Eastern Europe. A statement of civilization. The famous Yugoslavian writer Miroslav Krleža wrote about Maksimir in his 1926 Journey to Russia:

Where does Europe begin and Asia end? That is far from easy to define: while the Zagreb cardinals’ and bishops’ Maksimir Park is definitely a piece of Biedermeier Europe, the village of Čulinec below Maksimir Park still slumbers in an old Slavic, archaic condition, with wooden architecture from ages prehistorical, and Čulinec and Banova Jaruga to the southeast are the immediate transition to China and India, snoring all the way to Bombay and distant Port Arthur.

So, this wonderful place of leisure, so progressive at the time of its construction, shows the particular of position Zagreb in cultural discourse; an explosive position on ‘the fault line between civilizations’, as Samuel P. Huntington called it in The Clash of Civilizations?. This strange place on the brink of East and West has for centuries played an important role in the identification of Croatian culture, both from inside and out, and contributed to the Balkan’s reputation as the Powder Keg of Europe. For is it not inevitable that, when cultures so different from one another meet in one place, clashes ensue? Croatia is, in other words, on the frontier of the Culture Wars.*

Around the old city of Zagreb, beyond the comfort of the Viennese boulevards of the lower town and the picturesque alleys of the upper town, socialist-era architecture arises. Walking through the maze of streets and courtyards just south of the city center, a visitor might run into the impressive sight of the Rakete: a complex of three rocket-shaped towers designed by Centar 51 in 1968, which will soon be discovered by photographers with a brutalist fetish. And even further south, cut off from the rest of the city by the river Sava, is Novi Zagreb (New Zagreb). This part of town was built by the order of Marshal Tito to accommodate for a new, socialist urban life. Between the typical socialist high rises, a huge horse racing track was built, a new national library, and, more recently, the Museum of Contemporary Art. But despite these grand public works, social life in Novi Zagreb takes place mainly in the cafés of its malls and on the gigantic flea market Hrelić.

High rises in Novi Zagreb.

In this fragmented city with its many testimonies of a rich and turbulent history lives a unique culture. There is the culture embodied by the stately Viennese-style buildings of the Museum of Modern Art, the Archaeological Museum, the Art Pavilion, and the National Theatre, which take up unmistakably symbolic spaces along the promenades of the Green Horseshoe. But then there is also another, more interesting culture in Zagreb. This other culture emerged after Yugoslavia disintegrated in 1991 and Croatia became an independent state for the first time since the Middle Ages. Insiders refer to it as ‘independent culture’ or ‘non-institutional culture’.

Independent culture is just as present in the city center as the grand institutions, yet not immediately recognizable to the outsider. A stone’s throw away from the Archaeological Museum, hidden away in the arcade of a courtyard there is the small Galerija Nova. Galerija Nova is the only exhibition space in Zagreb structurally presenting art exhibitions which carry solidarity with migrants – a highly sensitive topic in this country on the border of the European Union. One block further still, in the back of another courtyard, Multimedia Institute and Hacklab MAMA is located, the base for Croatian media art and digital culture since the early 2000s. It also happens to be the best library in the fields of new media and commons in Croatia. A few minutes eastward by bike, in the poche Martićeva Street, there is a café which at first glance looks like any other. Once inside, however, it turns out that this place, which is called Booksa, is a hotspot of cultural life, where cultural workers come to drink coffee, meet, work, and read. A few tram stops from Booksa, in the fold line between the railroads and The Westin Zagreb, there is an old pharmaceutical factory. Today, it is a former squat called Medika. Instead of medicines, it now produces punk concerts and glitch art exhibitions.

I could go like this on for a while. Because with every visit to one of these places, one meets people and finds out about other places like it: the experimental dance company BADco., curatorial collective BLOK, news outlet Kulturpunkt, youth culture hub Pogon, anarchist bookshop Što Čitaš?, the old socialist Student Centre, platform organizations Clubture and Right to the city, and Documenta – Centre for Dealing with the Past. Like a distributed web, these organizations permeate the urban tissue of Zagreb. They make up a kind of village-like social system in which most people know each other personally and have often worked together at some point. Independent culture is a scene.

Now, if I’m raising the impression independent culture is either a subculture or a purely local phenomenon, I should correct myself immediately. Independent culture includes well-known, (internationally) established organizations. MAMA’s programs include many Croatian contributors, but also Catherine Malabou, Geert Lovink and Pussy Riot. The institute published the latest book by the French philosopher Jacques Rancière, one of my personal favorites amongst contemporary thinkers. WHW, the curatorial collective which directs Galerija Nova, works with internationally renowned artists like Mladen Stilinović, Sanja Iveković, and David Maljković. They have, moreover, been appointed as director of Kunsthalle Wien in the summer of 2019. These are just some examples to show that, while certainly embedded locally, independent culture is an internationally oriented scene.

It is hard to pinpoint exactly what type of culture is created in independent culture, while the practices of the various organizations in it differ so much. It includes but is not limited to dance, performance art, theatre, visual arts, new and old media, experimental cinema, festivals, education, community work, research, discursive programs, networking, and advocacy. It is clear that independent culture transgresses the boundaries of traditional cultural disciplines. The only general characteristic is that while all of these organizations work with culture, none work within the strict confinements of the art world or artistic production – a characteristic so common that it cannot define a scene. So, what is it that connects the scene, apart from personal relations, a shared urban environment, and the fact everyone in it does ‘something with culture’?

If anything, the organizations within independent culture are united by common political outlook (not to be confused with a political agenda). Their programming embodies a conglomeration of activist discourses leaning to the left of the political spectrum. Amongst other things, they focus on anti-fascism, pacifism, commons activism, feminism and queer activism, decoloniality, and ecological activism. Some would say that Yugonostalgia is rather common in independent culture, others would say that they’re Yugofuturist. In order to be able to have this political agency in the context of Croatia, which is predominantly ruled by right-wing and nationalist forces, the scene is organized separately from the state-funded cultural infrastructure. This shows by approximation what the independence is that ties together Zagreb’s independent cultural scene. Being rooted in grassroots activisms rather than large institutions governed by state and local governments, independent culture claims to work, indeed, independently from the dominant power of the state.

But contradictions abound. From the moment of its emergence in the 1990s, the independent cultural infrastructure depended largely on international philanthropist organizations such as the George Soros Foundation, the Rosa Luxembourg Foundation, and the European Cultural Foundation, as well as for-profit organizations such as the Viennese Erste Bank. Then, since the mid-2000s, international funds have retreated from Croatia, making independent cultural organizations more reliant on state funding, effectively incentivizing them to engage in advocacy, self-institutionalization, and cultural policy-making. It is questionable, then, how independent or non-institutional the independent cultural scene really is at this point. Is it a product of local urgency and grassroots engagement, or neoliberal and neo-imperial phenomena like globalization and cultural entrepreneurship? Is it possible that it is both? And if so, what is the interrelation between these forces?

In its analysis of independent cultures, Scenes of Indepencence is at times sharp and critical. The struggles it speaks of are real, and addressing them can, as I have learned, be sensitive at times. Yet, in the end, my account is always informed by solidarity. I deeply appreciate the existence of the organizations gathered under the umbrella of independent cultures. Sensing the political subjectivity and collectivity of the scene, however fragile, is a relieving and inspiring experience, especially when coming from Amsterdam, a place where neoliberal hegemony is by now so complete that elements of collective resistance are nearly completely absent from the circuits of cultural production.

My goal in writing the book has been to instrumentalize my semi-outside perspective and to create an analysis that makes sense to and is useful for the reader in the local context. At the same time, I reckon that the question of independence (in- and outside of culture) is a globally relevant one. My book, therefore, discusses two different (although not separate) questions: What does independent culture in Zagreb look like to an outsider? And what insights do the struggles in Zagreb’s independent culture provide into the regimes of global neoliberalisms?

Find the whole book here:

*The Balkans have been the battleground of military power struggles between West and East for centuries. The expansion of the Ottoman Empire was put to a halt by Western-European forces in the Balkans in the 16th and 17th century. In the early 20th century, the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the emergence of nation-states solidified the border between the liberal, Christian West and the Islamic East. Forced mass migrations and assimilations of ethnic and religious minorities took place, displacing Ottoman Christians West and Balkan-inhabiting Muslims East of the Bosporus. The friction caused between the ethnically and religiously diverse populations that had inhabited the Balkans for centuries, led to two Balkan Wars in 1912 and 1913. In 1914, by firing the mere couple of gun shots that killed Archduke Franz-Ferdinand of Austria, the Bosnian Gavrilo Princip triggered what was briefly considered the Third Balkan War, but is now known as the First World War. This series of events gained the Balkans their reputation as the ‘Powder Keg of Europe’, a reputation that was reinforced once again in reactions to the Yugoslav Wars in the 1990s. Moreover, the idea of the Balkans as a ‘Powder Keg’ was deepened by the rise of global identity politics heralded by the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989. In The Clash of Civilizations? (1993), the American historian Samuel S. Huntington argued that after what Francis Fukuyama famously called the ‘end of history’, the ‘great divisions among humankind and the dominating source of conflicts will be cultural. […] The clash of civilizations will dominate global politics. The fault lines between civilizations will be battle lines of the future.’ This theory was utilized, if not designed, to justify the US in upholding the aggressive foreign policy rhetoric it has used throughout the Cold War up to the present day. The argument that the Balkans are on the fault line of civilizations served in this agenda as a justification to keep regarding this area as the place where the West fights off the East.