The Exception of the Minorities: Pandemic and Subversion

A Dialogue with Federico Zappino by Lorenzo Petrachi

Federico Zappino is philosopher, translator and queer activist. He translated into Italian work of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Judith Butler and Monique Wittig. Among his recent works are Il genere tra neoliberismo e neofondamentalismo (Gender Between Neoliberalism and Neofundamentalism, ed. 2016) and Comunismo queer. Note per una sovversione dell’eterosessualità (Queer Communism. Notes toward a Subversion of Heterosexuality, 2019).

Lorenzo Petrachi is co-founder of the research group Dalla Ridda, in Bologna.

The interview appeared first in Italian OperaViva Magazine, April the 2nd 2020 and was translated by Eleonora Stacchiotti.

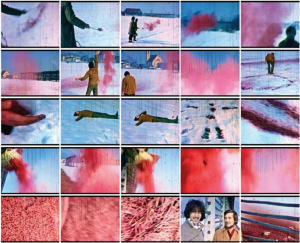

OHO group (Nasko Kriznar), Red Snow, 1969, 8 mm film, silent, colour film, 2’40”, Marinko Sudac Collection.

Lorenzo Petrachi: Almost two months after the declaration of the state of emergency, the measures that have been taken against the spread of Covid-19 are widening the gap that merges and separates two inherently different sets of signs. On the one hand, there are practices of control and domination that address the problem by holding the individuals responsible, for instance, as with the increasing attitude towards blaming the others, authoritarianism and militarization – which engender forms of slanderous psychosis. On the other hand, the exasperation of inequalities, the healthcare crisis and the fear for the coming bailout of the failing real economy are making tangible the variety of forms of solidarity and struggle, movements that emphasize interdependency over individualism. The pandemic definitely brought about a radical call as regards the question of our existence, especially by doubting the rationalities informing the government of the individuals and, more fundamentally, of the emerging entanglement of people and objects.

These organized practices with their particular subjects have proven to be unable to respond coherently to an adventitious, global problem and are on the verge of an inescapable transformation, although very uncertain in its nature. During one of the most recent mobilizations against neoliberalism in Santiago de Chile, a light installation on a building claimed No volveremos a la normalidad porqué la normalidad era el problema. In these recent days, a growing number of people are sharing this slogan on their social accounts, with a clear reference to the current crisis. Nevertheless, the current crisis is unprecedented for a number of reasons and this is why it is still not clear how this is going to turn out. It is still not clear how the joyful colors of (the more and more realistic) utopia are going to blend with the dull grey of the continuously extended state of exception. Are we then so sure that the “normal”, in these peculiar times, is our enemy?

Federico Zappino: I do not think I can be counted among the defenders of ‘normality’, because this term refers to the white, capitalist, hetero-patriarchal order established on the principles of environmental degradation, of violence and of institutionalized politics of inequality towards women, sexual and gender minorities, poor people, non-white people, people with disabilities and non-human beings. This is what the ‘normal’ actually looks like. Whoever takes part to a politicized minority perfectly knows that the ‘normal’ is the main problem. And those who are still willing to be included – without fighting for the subversion of it – are witnesses of the enormous fascination that the realm of normal has even on those who are oppressed. For this reason, I agree to the spirit of the light installation realized by the Chilean artistic collective Delight Lab, and I completely understand the reason why so many people borrow and make use of such a slogan in these melancholic, uncertain and endless days of collective grief.

However, we can first observe that there is a difference between a crisis induced by a political conflict waged by social movements in the order of “normality”, to which the Chilean slogan refers, and an epidemiological crisis. The current crisis is induced by a pandemic that has plummeted on a global society rather demobilized by the decennial crossfire of neoliberal and neo-fundamentalist policies (institution of the self-entrepreneur subject, dismantling or privatization of public and social services, restoration of the heterosexual family as a form of natural welfare), and which is politically managed through the establishment of a state of exception which – at least from what we can experience in Italy – replaces day by day pieces of ‘normality’ with increasing forms of coercive ‘social distancing’, disciplining, individual blaming, authoritarianism, even with the deployment of military means and practices.

The ‘normal’ that is being replaced by the state of emergency does not correspond with the white, hetero-patriarchal and capitalist order – that is, on the contrary, reinforced by the crisis. The state of exception is replacing ‘the public’. And while the State-Capital-Heterosexual Family tryptic gains centre-stage, the exceptional decrees show us how public space is precisely the precondition for the exercise – albeit unequal, and violently repressed if exercised by minorities – of all those freedoms such as walking, moving, gathering, expressing themselves, protesting, mourning a loss. Of all those freedoms, namely, which have meaning only in their collective and public exercise, and which fail when their condition of possibility fails.

To avoid any misunderstanding, what is at issue here is not whether the state of exception is justified by the need to stop the spread of the virus, whose causes, figures and territorial impact require further detailed analysis. What is a cause of concern now is that even now that health workers and all the workers in the production chains deemed ‘essential’ are denouncing the shortage of protective gear and the lack of the medical resources to face the pandemic, the state shows that it wants to ‘defend society’ by investing in population control devices such as drones, geo-location or monitoring of telephone cells, encouraging the population to relate those who break the rules of what is called ‘social distancing’, and much more. It would be irresponsible to consider these dark sides of the problem as relatively important, because they are evidently interconnected with the less dangerous aspects of this lockdown.

Lorenzo Petrachi: For instance, some argue that we are called to reflect on the traumatic desolation of the present in order to produce the inner feeling of existential crisis that will not be forgotten once the pandemic is over. Others insist that the pandemic is giving us the “chance” to witness first-hand the precariousness and the vulnerability of human life as the other side of the coin of the hegemonic vision of a subjectivity defined by sovereignty, ownership and entrepreneurial attitude.

Federico Zappino: I am not sure if I completely disagree with what you just mentioned. I believe that dwelling on loss, collectively lingering in mourning, rather than indulging the imperative of removal and restart at any cost, as if death had no effect on those who survive, can be not only transformative for the rethinking of the meaning of a community itself, but necessary. The point is that the labor of mourning does not need to suspend political criticism, as many, animated by dangerous forms of compassionate humanitarianism, suggest. On the contrary: if there was one thing that minorities learned from the HIV pandemic between the 1980s and 1990s, it is that the way to honor the many deaths was to politicize their causes, and to ‘ideologize’ in order to subvert them. It was precisely in that context that queer criticism took shape, for example.

I think this has to do with the fact that, as minorities, we know that life is vulnerable and precarious regardless of the pandemic: the likelihood that our life is taken away prematurely is a consequence of the marginal position we have in society. If we extend this assumption, we can understand that any form of vulnerability, including those induced by the pandemic, have never happened on an abstract level, but usually occur in specific social conditions. Hence, insisting on the vulnerability and precariousness of (non-)human life only makes sense in relation to the fact that an epidemic is such also, and perhaps above all, in relation to the sanitary means and structures that such a situation requires – or on the contrary, the absence of such means and structures. The heavier the cuts in medical resources, the more authoritarian the emergency measures. This must be made clear. If then we can also grasp the eugenic subtext underlying this connection (in Italy there are a only few thousand intensive care beds for a population of sixty million inhabitants), we can easily understand how it makes no sense to understand as two distinct things ‘governmental’ power and ‘sovereign’ power of life and death over the population.

There would be no need to threaten the application of eugenic criteria for access to limited places in intensive care if these places were not limited, and if their number was proportionate in an egalitarian sense to the idea that the population, in its complex, it is vulnerable. What constitutes an insult to vulnerability is the neoliberal brutalization of public health resources and structures. Clearly, this cannot only be reduced to a critique of what has been done so far by the political classes that have facilitated neoliberal measures, but must be turned to a present demand for a radically different future: we must no longer listen, not even by mistake, that some subjects ‘deserve’ more than others access to medical treatments. This ‘value’, I fear, has to do with their productive and reproductive capacity of species and whiteness, and which, therefore, ratifies and consolidates the differential value accorded to people in line with principles like gender, race, age and psychic and physical ability. A materialistic and egalitarian commitment to vulnerability requires us not to accept death – or the need to choose who deserves to live – as a tragic fatality.

Lorenzo Petrachi: The connection that you make between the healthcare crisis – that has to do of course with the public financial cuts – and the growing authoritarianism of the governmental measures is fundamental in various ways. Pointing at this specific interdependence allows us to become aware of the difference between a disciplinary society and ours, by avoiding easy associations between the condemnation of violence of the state and the latter’s irrationality. What we are highlighting here is not the excessive suspension of the exercise of fundamental freedoms, but the modes of operation of a number of governmental rationalities working together. Your analysis also reworks the concept of ‘normal’ that, similarly to ‘power’, results to be less monolithic than what it seems to be at first glance.

Federico Zappino: My idea is that only emphasizing the multiplicity of rationalities of government we can protect ourselves from the risk of channeling our critical and political attention in one-way ways, as it happened too often on the sidelines of the issuing of emergency decrees. This is no time for binary oppositions. No fans needed. We collectively need to keep a watchful eye on a number of elements like the legitimacy of exceptional measures, the pandemic-induced reshaping of the relationship between capital and labor, the instrumental function of authoritarianism to the neoliberal decimation of public health resources, or the eugenic drifts that threaten, in an unacceptable way, to preside over the distribution of these scarce resources.

Moreover, we need to be aware of the strengthening of various forms of nationalism, induced by the fact that health systems are national and that, in the absence of global and common forms of health organization (as Judith Butler seems to suggest), any vaguely cosmopolitan idea fails at the first pandemic, as evidenced by the closure of all borders. We must be aware of the discursive and mediatic invisibilization of homeless, migrant, disabled and queer populations. Finally, it is of vital importance to acknowledge the hegemony of the heterosexual family and the re-naturalization of the exploitation of work and the violence based on gender that are given within it.

At the same time, I believe that it is fundamental to emphasize that there is no reason not to go back to ‘normal’ if we understand the normal as the restoration of the public space. I believe that minorities should not be taught that public space is constituted and torn by power relations: yet it remains the only space for social and political transformation. Therefore, going back to ‘normal’ is necessary. We need to go back to “normal” to enable the meeting of bodies, freedom of movement, freedom of assembly, social conflict, forms of solidarity that fall outside the capitalistic monopoly of digital platforms. Having the possibility of gathering with other people in the public space to demonstrate, to protest, to mourn – also in the name of those who cannot do it, so to go against such an impossibility: aren’t these forms of the ‘normal’? The point, if anything, is to start immediately to understand what needs to be done once we have returned, and net of what we will find there, certainly not by our choice. The paradox created by the state of exception is that we must go back to ‘normal’ in order to subvert it. We can subvert it by mean of the political, cultural and social instruments that are part of the public space that we envision as radically democratic.

The state of exception cannot be a condition of social transformation, unless this is done through violence – a perspective that does not look intriguing to me. As I understand them, the claims of minorities are requests of a radical subversion of cultural, political and economic factors causing the social differences at the base of systematic inequalities. But the strength of these instances does not need to double the violence that produces them: the anger and the grief we feel can be turned into a transformative politics rather than a violent one.

Lorenzo Petrachi: As regard as the coaching to keep a daily routine during the lockdown, it is interesting to observe how the political use of certain kinds of normality incites the population to keep a productive rhythm with lines like “Put your makeup on as if you were going to work”, “Set your daily goals”, “Stop wasting time and set a schedule.” It is precisely this efficient lifestyle, this form of entrepreneurial and proprietary freedom that is showing its inconsistency and its being unsustainable during this moment of global crisis. The fact that the exceptional measures stopping the ‘normal’ are still promoting this mode of existence – by reproducing the ordinary repressive structures that you, in your book Comunismo Queer, put at the intersection between modes of production of the subjectivities, of relational spaces and of social relationship – is even more revealing about the true nature of the ‘normal’. The order to stay-at-home, for example, not only does not take into consideration the homeless, but also does not take into account the limits and the iniquities of the majority of people that are living most of the times with their heterosexual family or on their own. This is what is emphatically supported by the popular banner hanging outside a Spanish house: “La romantización de la cuarentena es un privilegio de clase.” The presumably good sense to prioritize basic necessities on an institutional, economic and individual level is based once again on an established meaning of ‘necessity’, that does not deal with the impact of such measures on different subjectivities. How can we shy away from this evidence?!

Federico Zappino: If we observe the ‘micropolitics’ of this state of exception we can see that it needs to ensure the reproduction of ‘normality’ right in the middle of its suspension. This exhorts us to look at normality in a less dogmatic way, detecting different regimes of competing normalities, so that it is evident that the suspension of a certain kind of normality takes place by means of the corroboration of the modes of production which, historically, come together in its determination.

It was not necessary to wait for a pandemic to find out that the capitalist modes of production operate by transforming ecosystems deeply and irreversibly, to the point where, as some argue, pandemics should be understood as anything but dysfunctional as regards the modes of production themselves. Yet, since the epidemic broke out Xi Jinping has repeatedly (often turning to Trump) asserted that in no way will the virus affect the Chinese economy, which, from his point of view, will restart stronger than before. In Italy too, we are witnessing a precise political will to maintain productive ways and sectors whose ‘essentiality’ is to be proven, and in working conditions often unsuitable for the context of a pandemic. This allows us to highlight in new ways the dependence between a specific mode of production and the form of life it generates, the latter which continue to depend on the former even if the price to pay for this dependence is life itself.

The same goes for all the modes of production of subjectivity which, from my perspective, offer human and symbolic resources by means of which capitalism can assert and reproduce itself. In Italy, the anthropologist Miguel Mellino brought attention to all the racist limits of the governance of the pandemic, insisting that migrants – who often work in agricultural production chains – are made totally invisible by media and institutional discourses. Mellino wonders: “Are there no infections among migrants? Are there no hospitalizations? Or maybe they are not assisted or not even counted? Or are they not even considered as worthy of representation, speech and even less of tampons?” For Mellino, in other words, the state of exception exacerbates a racist rift, reproducing specific white coordinates of social reproduction. In my view, the state of exception is also the product of a heterosexual rift.

While psychologists and pundits urge men and women to dress and put on make-up as if they were going to work – that is, to reproduce the heterosexually regulated ‘society’ even in the times of ‘social distancing’–, the lives of those constituting an exception in the exception remain equally invisible from the public discourse, still obliged to abide by the criminally binding injunction to stay-at-home: the lives of those who do not have a home or an income, and the lives of those who live in situations of mental distress – and we know how many women and queer and trans people live in situations of housing, income and psychic precarity.

Likewise, women trapped in violent heterosexual contexts who, due to the suspension of public space, can only count on incomplete forms of support from anti-violence centers or other supportive and solidarity relationships; women who bare the full domestic brunt of taking care of children, of elderly or of sick or disabled people, in the general suspension of school and social activities; queer, trans, gay, lesbian, bisexual adolescents and pre-adolescents, in contexts of legal and economic dependence on violent or hostile parents (in most cases fathers), and especially in non-urban contexts; sex workers, for whom the alternatives are either risking exposure in the suspended public space or having insufficient financial resources to pay bills and rent. The list could go on: what is relevant here is that public silence on these issues is only one of the effects of the “heterosexual social contract”, as Monique Wittig would call it. Just like the capitalist modes of production and the white domination, what I call “heterosexual mode of production” is inscribed in the material and cultural hierarchies of the exceptional government of the pandemic crisis, and is clearly reinforced by it. Precisely for this reason, we need to present it with its limitations, in a way that cannot be deferred.

Lorenzo Petrachi: I would like to go back to the issue of public space again, which you have defined as a necessary condition for social and political transformation. In the state of exception, on the contrary, it is not possible to protest using the traditional methods of assembly and demonstration, and even the possibility of striking, in its various forms, is precluded to many of us. Furthermore, the only means we have to communicate and to express our dissent – means that for a not negligible part of the population are unfortunately the only ones imaginable – are owned by private companies. Yet, now more than ever, the success of a number of demands seems not only urgent and unpostponable, but also more plausible. If it is true that restrictive measures unfolding before our eyes have definitively re-entered the field of the politically contingent, the same must be said also for the unprecedented horizons opened by the crisis.

Consider, for example, the claims relating to the suspension of rents and bills, the claim for universal income, the visibility of prison conditions, the certainty of the value of public health… To all this we must add not only the elaboration of unheard practices of social solidarity even in times of ‘social distancing’, but also the awareness that comes with each of these instances. In other words, are the suspension of public space and the relative difficulty in organizing the struggles sufficient grounds for postponing the articulation of our claims until later? We must undoubtedly return to normal in order to have the necessary means to transform it completely; but can we miss, in this situation and in its narrow limits, the opportunity to create a precedent? We are encountering an exceptional scenario. It is a matter of understanding what about this exceptionality is destined to become transitory and what, for better or for worse, will establish itself.

Federico Zappino: Hoping to go back to ‘normal’ in order to have the means of public space that allow for its subversion, does not mean postponing this subversion towards an indefinite future. Just as the state of exception induced by the pandemic illuminates problems and contradictions of a social system based on inequality and violence, and aims to preserve it, at the same time it begins to favor the possibility of forms of solidarity and resistance which, for the first time in a very long time, seem to be on the brink of possible. In fact, they can create a ‘precedent’. The demand for an income independent from productive work is perhaps among the most important and the most transformative of social demands. However, its effectiveness, and that of any anti-capitalist practice, will depend largely on the way in which, in the public space, we will manage to thematize and subvert the specific modalities that exploitation and exclusion assume, because each of these modalities refers to specific ways of production that concur in defining what, in generic terms, we then call “exploitation”, ‘exclusion’ and, above all, ‘capitalism’.

When we talk about exploitation, are we sure to include within it also the exploitation of women’s domestic work by men, in the vast majority of heterosexual cohabitative contexts? When we talk about the exclusion of the minorities from the public space, are the material and economic implications of this concept clear for us or do we limit ourselves only to those aspects that we like to define as ‘cultural’? Is it clear for us that the cultural construction of entire social groups as ‘diverse’ means exposing them to the greatest likelihood of poverty, indigence, violence and premature death? Are the links between symbolic and verbal violence and its substantial premises and material consequences clear? If we do not keep all these implications in mind, and if we do not endeavor to subvert them, a highly transformative instrument such as the universal income can easily be turned into its opposite, that is, an instrument to normalize already existing power relations.

The vast majority of women will continue to serve a man inside the house – but with an income; and so on. Any means that aspire to be ‘universal’, however, must deal with the fact that the universal has always been internally torn by power relations, and in the absence of an effort aimed at healing that fracture, every universality will be destined to reproduce as much. This aspect is very difficult to understand if you are not part of a minority group, or if you are not aware of it. My idea is that only by thematizing and keeping together all the forms that exploitation and exclusion assume, we can understand what capitalism needs in order to function – and indirectly, also what needs to be done to subvert its unjust and violent order. This, at least, is what I have attempted to illustrate in Comunismo Queer. Until a few weeks ago, the various currents of queer, feminism, anti-speciesism, decolonial thought could be conceived as utopian, brave, full of hope and anger, certainly ridiculed by those defending, consciously and unconsciously, the sad and criminal heteropatriarchal, white, capitalist and speciesist ‘normal’. The exceptional thing is that they could instead constitute the theoretical framework from which to draw inspiration from now on for the next transformative and instituting practices.