I Present You with Myself: Facebook Avatars and Apple Memoji, or a Brief Account of the Evolution of Emoji*

By Natalia Stanusch

While swiping through Facebook’s people you might know suggestion window, I got genuinely dazed. Among profile pictures of photographed faces, I saw a cartoonish face with exaggeratedly wide-opened eyes and mouth with chopper-like teeth. Her vein-less and wrinkle-less face was as texture-less as her licked brown hair. She was set against a plain purple background, suspended in digital nothingness. And yet when I read the name below the picture, I realized that I know her. This was my friend. This was also Facebook’s new feature – Facebook Avatar. Facebook introduced it gradually over the course of a year, but only after it conquered the US on May 15, it conquered the rest of the globe, with lots of news outlets writing about it (for example CNN, CNBC, TechRadar, and Adweek). But Facebook, which used to be attaching names to real faces, now gives users the option to present themselves as ‘personalized emoji.’ What should we make out of it?

With Covid-19 cozily sitting at our global table for the past few months, we collectively leaped into online communication. There is no better moment than now to think about how we simile, joke, laugh, and cry online, especially while we are doing it now more than ever. The short answer is: 🤣😄🙁 and

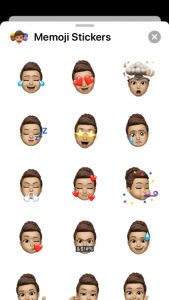

Without face-to-face bodily cues, emoji have been extensions of our sociality and personality online. Facebook Avatar, just like Apple memoji, is supposed to represent you in the virtual space and function like emoji which look just like you. What Apple memoji, Facebook Avatars, and their grandpa Bitmoji – let’s call them all personalized emoji for now – have in common is that they embody, upgrade, and extend what emoji offered: a real-time catalogue of ourselves, where we can pick and choose our emotions, looks, identities. We might think of them as silly. But they are not. Instead, they are becoming, more and more, us.

How did we get here? On the origins of 🤔💬📲

Emoji is a yellow smiley face that one chooses from an emoji keyboard on the smartphone. Emoji is one of the seven reactions Facebook offers. ‘Emoji’ is a borrowing from Japanese 絵文字, where ‘the e of emoji means “picture” and the moji stands for “letter, character.” So, the definition of emoji is, simply, a “picture-word”’.[1] The history of digital smileys goes back to the last decades of the twentieth century, but since its beginning it was artificially constructed by designers and engineers for communication companies. Apple initiated the emoji craze by introducing the emoji keyboard on their iOS devices back in 2011. By 2015, emoji were everywhere. Emoji fit perfectly into our communications style, our ‘hybrid writing’,[2] which mixes up written, audio, and visual messages into one digitalized flux. Emoji and personalized emoji both resemble what they send for (a sad face is a sad face) and replace specific words (sad is replaced by a sad face). However, emoji are not words. They are visualizations of emotions and feelings, something which is lost in the disembodied online presence. Emoji thrive as the quintessence of online communication, being digital substitutes for both body and emotion. Emoji take the self out of the conversation by replacing it with a menu of yellow faces.

Emoji and emotion

Can one genuinely choose 🙁 over 😄? To understand personalized emoji, we have to talk about emoji first. Up to 70 percent of our daily communication comes from non-verbal cues,[3] but online, once the screen is tapped, the message is lost. Emoji translate these non-verbal cues into the digital communication space. While emotions materialize in our facial expressions, the way in which they materialize is more classifiable than emotions themselves. Paul Ekman is considered one of the first psychologists who studied facial expressions as a code. By studying the so-called ‘micro-expressions – fleeting facial features’,[4] Ekman created an ‘atlas of emotions,’ with over ten thousand facial expressions, that is now used broadly by scientists, semioticians, and even the police. His goal was to identify the specific biological correlates of emotion and how they manifest themselves in the configuration of the parts of the face.[5]

His major findings indicated that emotions materialize in facial expressions in a similar manner across Western and Eastern cultures, with limited and predictable variations involved. Putting aside whether it is an outcome of inherited or learned behavior, emoji embody the facial materialization of emotions. Whatever the feeling is that you might feel, emoji visualizes it for both you and the person who’s reading it. So maybe emoji are actually a pretty genuine representation of ourselves?

If so, we are pretty happy people. In the past years, several studies implicated a relation between emoji use and users’ positive emotions. Emoji show playfulness,[6] up to 70% of emoji used express positive emotion,[7] and ‘the emoji code is used primarily to enhance the positive tone of an informal message’.[8] More recent research proved that rather than to praise the positivity of the smiley face, one should see it as a mask. Online, positive content and reactions are more likely to ‘receive reinforcement’[9] than their negative counterparts. To sum it up: you will not genuinely choose 🙁 over 😄, at least if you want to get likes and retweets.

For one thing, emoji and personalized emoji force the user to self-reflect when choosing them. You have to reflect upon how you feel and what emoji represents your feeling best at the moment. It is a receiver-oriented self-reflection, however. You don’t reflect upon your emotional state to understand it or fix it but to translate it so that it is understandable to other users. It is a mediated and artificial representation of invisible and immaterial emotions. One study suggests that over ‘72 per cent of British eighteen to twenty-five-year-olds believe that Emoji makes them better at expressing their feelings’.[10] But while face-to-face communication is involuntary and unconscious, emojis are voluntary and conscious. Emoji provide the user with the agency to choose emotions as if they were a catalogue of clearly-defined products, a menu of dishes that always taste the same. Emoji seem to create an obfuscated view of communication, where meaning is stable and visible, and each feeling can be directly named, each emotion classified, and each message delivered.

Emoji Corporation: Facebook and Unicode

Basically, emoji, memoji, Facebook Avatar, and Bitmoji, all look pretty much the same across different platforms and express the same emotions. Reason? Only a few companies create their own emoji, personalized emoji, and their design. The transition of emoji to the mainstream was possible mostly thanks to an organization called Unicode. Unicode establishes a universal code for emojis across all platforms. But Unicode itself is made up of big players: ‘Oracle, IBM, Microsoft, Adobe, Apple, Google, Facebook and Yahoo, with (…) the committee reps of these tech companies are overwhelmingly white, male, and computer engineers – hardly representative of the diversity exhibited by the global users of emojis’.[11] These companies not only decide how emoji look across different platforms and how they vary (famous case of a water gun on iOS devices showing as an actual gun for Android and Samsung users), but which emoji exist and which don’t. You can petition to Unicode to include a new emoji (for example, the dumpling emoji was ‘democratically’ added because of a single petition to Unicode), but the final decision is still taken by ‘technological authorities’.[12] While both emoji and personalized emoji are supposed to facilitate face-to-face cues online, your body and emotions have to first fit into Unicode’s emotion boxes.

Social media companies took major steps to show that they care to please the digital mortals. Only a few weeks ago, Facebook added a new reaction option, or rather a new emoji reaction, called Care. The yellow smiley holding a heart is a cute gesture but is not that much help in the time of a global pandemic. Some memes quickly pointed that out.

(translation: I knew that you were very concerned with the pandemic, so I prepared for you a hugging reaction. Oh, Vishnu! All our problems resolved! We have a hug!)

But Facebook, similarly to other companies, does it for a clear purpose: these emoji reactions ‘comprise a simpler classification than the thousands of emoji’.[13] Despite the popular phrase that ‘data is the new oil,’ a growing problem is a flood of data most corporations begin to experience. The amount of data collected is meaningless for algorithms which are not able to analyze it efficiently. Emoji are easier to classify by algorithms, and are incomparably simpler and more limited than any language. David Auerbach, a former Microsoft and Google software engineer, explains Facebook’s decision behind employing emoji reactions as follows,

“Those classifications permit Facebook to match users’ sentiments with similarly classified articles or try to cheer them up if they’re sad or angry. If reactions to an article are split, Facebook can build subcategories like “funny-heartwarming” and “heartwarming-surprising.” It can track which users react more with anger or laughter and then predict what kinds of content they’ll tend to respond to in the future. (…) If the restricted set of six reactions has the effect of narrowing emotional diversity, social media and advertising companies view this trade-off as the necessary cost of gathering better data on users.”[14]

Personalized emoji are just another step in this ongoing simplification of us for the sake of algorithms. But Emoji as ‘emotion visuals’ are no longer enough. We have to be given new features to keep up the digital hype. Despite the boredom factor, emoji are more than just clues: they represent us. And we want to be represented more and more accurately, and this is where personalized emoji come in. As Jeremy Burge, an emoji historian and the founder of Emojipedia, explained,

“Increased representation on our personal devices is important, and companies have recognized this by offering alternatives to the Unicode emoji set in recent years. Apple has Memoji, Samsung has AR Emoji, and Google has Minis, which all allow far more customization of individual people than Unicode could ever offer. (…) they do fill a role that Unicode may never be able to.”[15]

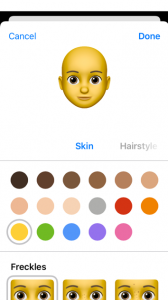

Me, my, mine: memoji

Recently, Apple has been promoting an online Worldwide Developer Conference on their website. Knowing Apple, one would expect highly saturated images of cool-looking people embodying the idea of powerful individuals with MacBooks on their lap. But not this time. Their promo image depicts three figures emerging from the black background: three memoji. They are looking at their virtual MacBooks, and are just as colorful and individualized as actual Apple people would be. Cool design, you can say, and I would agree, but there is much more behind this image than solely its design. Apple is substituting real people with their virtual memoji/avatars/personalized emoji. This design shows the confidence that viewers will understand that memoji are not cartoonish characters, but real, professional, and cool people. These people are online, hence the looks. You want to be as cool as they are? You better get your memoji ready.

While most of us might use personalized emoji because they are ‘fun,’ or to be ‘cool,’ those who design them take it seriously. Apple and Facebook take one step at the time in familiarizing millions of users worldwide to the idea of personalized emoji; it took them six years to arrive at the point where my friends start to replace their profile pictures and comment with their Facebook Avatars, while others WhatsApp me with their memoji. Since my friend changed her Facebook profile picture to her Facebook Avatar, is it still a picture of her? Apple would say yes. I don’t think the answer should seem so obvious.

The 0-1 mask

The idea of an avatar has long been present online. In gaming, one chooses how to “represent oneself during the ensuing social interactions”[16] in the game. Online games provide the opportunity to “graphically represent oneself”,[17] but this representation has nothing to do with one’s physical appearance. Sure, I can choose to have brown eyes like in the real life, but I can choose anything else too, just like I choose to have a sunflower as my WhatsApp profile picture it. I decide on what will be my embodiment in an image as if I was creating a logo that represents me but not my physical looks. But now, there’s memoji. While personalized emoji are your digital (physically-based?) representation, they are used in seemingly daily, ‘real’ conversations.

A virtual world of a game feels way less real than Facebook. Since Facebook, Instagram, Whatsapp, and iMessages took over our sociality from the physical world, it is still real sociality, with real issues rather than virtual quests, fights, and deaths. The problem with memoji and Facebook Avatars is that they assume that either the digital can fully replace the physical with no loss whatsoever, or that digital is indeed the only real realm there is. How I look physically does not matter, what I do physically does not matter, what I feel physically does not matter, but what my memoji is doing does matter, because that’s what others see. To be socially accepted, to be authentic, to express oneself, one enters the highly controlled and standardized system of personalized emoji, provided and controlled by a few powerful who, as stated before, care little or less about real-life implications of their inventions.

You can say that one’s avatar – memoji, for example – cannot replace one’s physical self. But psychologically speaking, one study points out that the more you use the avatar in the game, the more you feel like it was you; ‘in high-use situations, users’ neural activation patterns indicating an emotional connection with their avatars have been measured as roughly equal to the neural patterns indicating an emotional connection with their biological selves’.[18] Think which one you would use more frequently and more emotionally: an avatar-character in a game or a personalized emoji in texts on Messenger, Facebook comments, etc., on daily bases, hour after hour, week after week. As one more and more uses the mask of personalized emoji, one becomes the mask.

My digital ‘I’

Emoji design our emotion just as memoji design our self. Each design element impacts us, mostly without ‘conscious intention or awareness’,[19] such as color. Research proved that color is ‘a dominant visual feature affecting consumer perceptions and behaviors’.[20] Already in 1942, it has been proposed that colors such as yellow – the color of emoji – are ‘naturally experienced as stimulating and disagreeable, that these colors focus people on the outward environment, and that they produce forceful, expansive behavior’.[21] Recent research claims that ‘we alter our facial expressions to match the emotivity of the emoji. Without knowing, we end up mimicking the emoji expression’[22] or even that ‘emoji might indeed play a role in shaping cognition and possibly consciousness.’[23] Still, there is little or less research done on how emoji and memoji influence our self-perception.

Think of the 2009 film Surrogates, where a part of society remotely controls humanoid robots, which are their avatars through which they interact with others. Some reject this concept, resulting in a break with the society: ‘the enhanced separate themselves from the unenhanced, left to fend for themselves in poverty’,[24] yet for humans, as ‘embodied beings, something is missing from disembodied experience’.[25] While both emoji and memoji provide digital materialization of oneself, the cliché that by this avatar-enhancement, we ‘are missing something deeply human’.[26] should not be taken for granted.

We enter a new digital ground where design covers much more than just data harvesting and software. Memoji, and any of its lookalikes, is an unprecedented mix of digitalized techne and psyche. Who are we in it? Rather than talk data, we should talk human. What are the consequences of substituting oneself with personalized emoji? What are its implications for the continuous human-tech merge? How might it intrinsically change the notion of sociality, emotions, communication, and human? Should I paste here my friend’s Facebook Avatar/memoji, or should I see it as a picture of her which is inherently and only hers to use, publish, and show? Who owns your personalized emoji legally speaking? Can anyone use it after you die? You can become this digital doll though. Embrace your personalized emoji: your digital you. There’s no way back, right? It’s pretty, it’s fun, it’s free, it’s equal for me and you: it’s precisely everything that the real world isn’t. But, at some point, you will have to face your real, physical face.

—

Biography

Natalia Stanusch studies Communications and Art History at John Cabot University, Rome. Her research interests include the visual fusion of digital and physical, the intersection of new media arts and social media and issues related to digital images. She is the creator of Hashtagart.blog where she questions recent developments from the crossroad of new media arts and digitalization. She’s been also involved in several projects in the past years, for example as a co-author of “Kid-Directed Family Vacation Planning: Using Ideas from Creative Kids Around the World” (2016) and was an editorial assistant for “The Social Issue in Contemporary Society: Relations Between Companies, Public Administrations and People” (2019).

Notes

* This text was inspired by a research paper presented at Professor Donatella Della Ratta’s course CMS 365 ‘Selfies and Beyond: Exploring Networked Identities,’ John Cabot University, Spring 2020.

[1] Marcel Danesi, The Semiotics of Emoji, London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2017, pp. 2.

[2] Danesi, The Semiotics of Emoji, pp. 5.

[3] Vyvyan Evans, The Emoji Code: How Smiley Faces, Love Hearts and Thumbs Up are Changing the Way We Communicate, London: Michael Omara Books Limited, 2017, pp. 78.

[4] Vyvyan Evans, The Emoji Code, pp. 75.

[5] Danesi, The Semiotics of Emoji, pp. 62.

[6] Dwi Noverini Djenar, Michael C. Ewing and Howard Manns, ‘Youth and language play,’ in Dwi Noverini Djenar, Michael C. Ewing and Howard Manns, Style and Intersubjectivity in Youth Interaction, Boston/Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018, pp. 193-230.

[7] Danesi, The Semiotics of Emoji, pp. 22.

[8] Petra Kralj Novak, Jasmina Smailović, Borut Sluban, and Igor Mozetič, ‘Sentiment of Emojis,’ PLoS ONE 10.12 (2015), doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0144296.

[9] Chiara Rollero, Adriano Daniele, and Stefano Tartaglia, ‘Do men post and women view? The role of gender, personality and emotions in online social activity,’ Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 13.1 (2019), http://dx.doi.org/10.5817/CP2019-1-1.

[10] Evans, The Emoji Code, pp. 26.

[11] Evans, The Emoji Code, pp. 23.

[12] Danesi, The Semiotics of Emoji, pp. 47.

[13] David Auerbach, ‘How Facebook Has Flattened Human Communication,’ Medium, 28 August 2019, https://medium.com/s/story/how-facebook-has-flattened-human-communication-c1525a15e9aa.

[14] Auerbach, ‘How Facebook Has Flattened Human Communication.’

[15] Jeremy Burge, ‘New Emojis Are Here. We’re Not Ready,’ Medium, 12 November 2018, https://onezero.medium.com/new-emojis-are-here-were-not-ready-e7f9de4779d2.

[16] James K. Scarborough and Jeremy N. Bailenson, ‘Avatar Psychology’, in Mark Grimshaw, The Oxford Handbook of Virtuality, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014, p. 2. Available at: doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199826162.013.033.

[17] Deborah Abdel Nabi and John P. Charlton, ‘The Psychology of Addiction to Virtual Environments,’ in Mark Grimshaw, The Oxford Handbook of Virtuality, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014, p. 6. Available at: doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199826162.013.022.

[18] Scarborough and Bailenson, ‘Avatar Psychology’, p. 5.

[19] Andrew J. Elliot and Markus A. Maier, ‘Color and Psychological Functioning,’ Current Directions in Psychological Science 16.5 (2007): 251, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20183210.

[20] Ioannis Kareklas, Frédéric F. Brunel and Robin A. Coulter, ‘Judgment is not color blind: The impact of automatic color preference on product and advertising preferences,’ Journal of Consumer Psychology, 24.1 (2014): 88, doi:10.2307/2661798h.

[21] Andrew J. Elliot and Markus A. Maier, ‘Color and Psychological Functioning,’ pp. 250.

[22] Danesi, The Semiotics of Emoji, pp. 172.

[23] Danesi, The Semiotics of Emoji, pp. 172.

[24] Dónal P. O’Mathúna, ‘Movies,’ in “Movies.” In Robert Ranisch and Stefan Lorenz Sorgner (eds) Post- and Transhumanism: An Introduction, Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2014, pp. 294.

[25] Dónal P. O’Mathúna‘Movies,’ pp. 294.

[26] Dónal P. O’Mathúna‘Movies,’ pp. 294.

References

Auerbach, David. ‘How Facebook Has Flattened Human Communication,’ Medium, 28 August 2019, https://medium.com/s/story/how-facebook-has-flattened-human-communication-c1525a15e9aa.

Burge, Jeremy. ‘New Emojis Are Here. We’re Not Ready,’ Medium, 12 November 2018, https://onezero.medium.com/new-emojis-are-here-were-not-ready-e7f9de4779d2.

Danesi, Marcel. The Semiotics of Emoji, London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2017.

Djenar, Dwi Noverini, Ewing, Michael C., and Manns, Howard. ‘Youth and language play,’ in Dwi Noverini Djenar, Michael C. Ewing and Howard Manns, Style and Intersubjectivity in Youth Interaction, Boston/Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018, pp. 193-230.

Elliot, Andrew J. and Maier, Markus A. ‘Color and Psychological Functioning,’ Current Directions in Psychological Science 16.5 (2007): 250-254, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20183210.

Evans, Vyvyan. The Emoji Code: How Smiley Faces, Love Hearts and Thumbs Up are Changing the Way We Communicate, London: Michael Omara Books Limited, 2017.

Kareklas, Ioannis, Brunel, Frédéric F. and Coulter, Robin A. ‘Judgment is not color blind: The impact of automatic color preference on product and advertising preferences,’ Journal of Consumer Psychology, 24.1 (2014): 87-95, doi:10.2307/2661798h.

Nabi, Deborah Abdel and Charlton, John P. ‘The Psychology of Addiction to Virtual Environments,’ in Mark Grimshaw, The Oxford Handbook of Virtuality, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199826162.013.022.

Novak, Petra Kralj, Smailović, Jasmina, Sluban, Borut, and Mozetič, Igor. ‘Sentiment of Emojis,’ PLoS ONE 10.12 (2015). doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0144296.

O’Mathúna, Dónal P. ‘Movies,’ in “Movies.” In Robert Ranisch and Stefan Lorenz Sorgner (eds) Post- and Transhumanism: An Introduction, Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2014, pp. 287-298.

Rollero, Chiara, Daniele, Adriano, and Tartaglia, Stefano. ‘Do men post and women view? The role of gender, personality and emotions in online social activity,’ Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 13.1 (2019). http://dx.doi.org/10.5817/CP2019-1-1.

Scarborough, James K. and Bailenson, Jeremy N. ‘Avatar Psychology’, in Mark Grimshaw, The Oxford Handbook of Virtuality, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199826162.013.033.