Written by: Pamela Nelson

Sewing is an act of mindfulness. When we embroider or engage in other creative activities like painting or sculpting, our perception of time can become distorted and give the illusion of ‘slowing down’, as discussed in ‘The Restructuring of Temporality During Art Making’ by Ariana van Heerden. In a fast paced, technocentric world, we must not underestimate the power of being able to slow down.

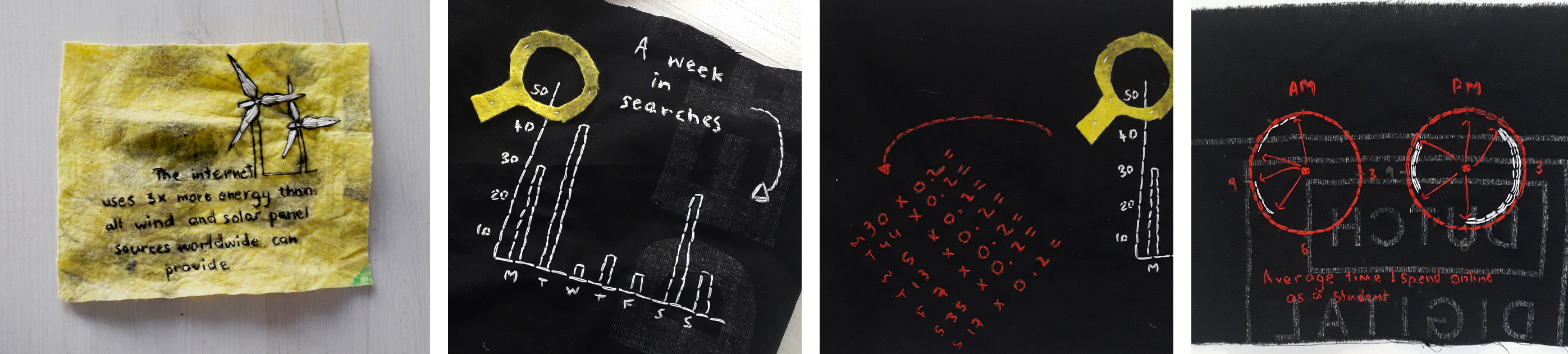

Recently, I have been using stitch as a way of understanding my relationship with technology, while at the same time reflecting on the harmful environmental impact that technology can have. I did this by monitoring my own internet usage and habits and trying to estimate my carbon footprint for certain periods of time. I embroidered diagrams and data onto pieces of whiteboard cloth or old tote bags as a way of visualising this information. I set aside time for myself to embroider that was intended to be ‘tech-free’; no laptop playing Netflix in the background, no podcast streaming from my phone. I was successful for the most part in doing so, but in some cases I gave in to watching a show or listening to a Spotify playlist.

Lockdown

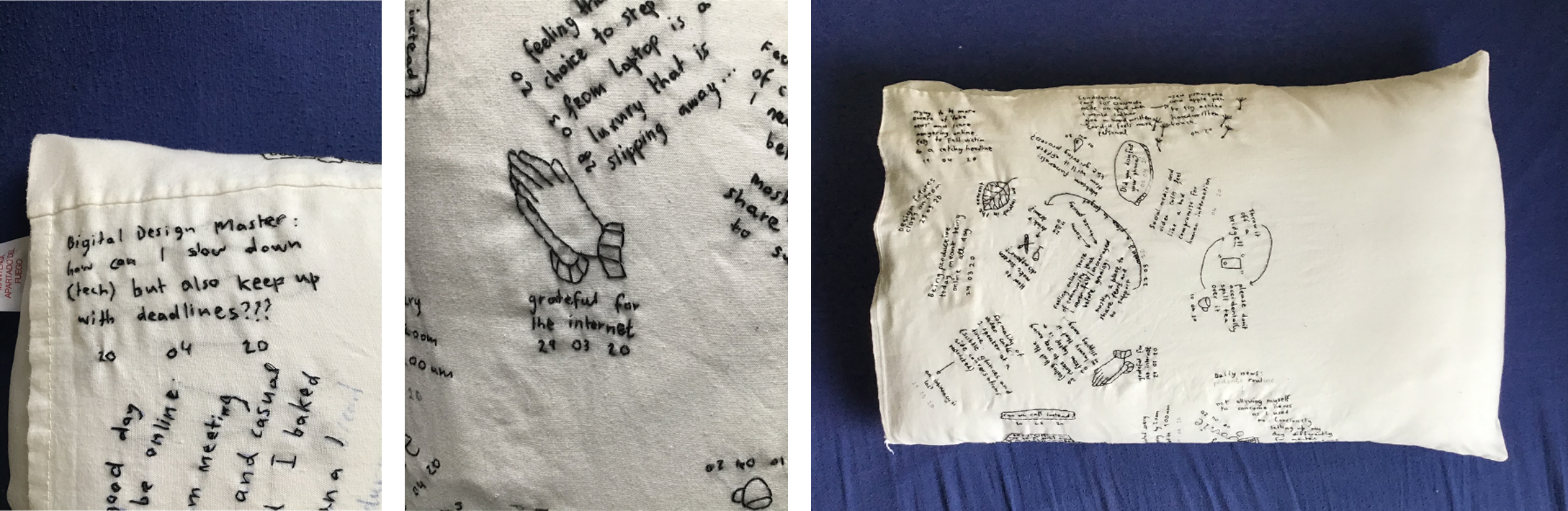

During lockdown, my focus shifted to my changing relationship with technology and growing reliance on it due to Covid-19. I had a ‘worry pillow’ that I would embroider with passing thoughts and changes I was noticing during this time. I found the process of logging and dating these observations useful for keeping track of my ever-changing outlook on technology. I noted the tension between wanting to be offline but at the same time needing to be online for other work, I thought about ways to allow for a more authentic social experience over Zoom by brainstorming how to ‘make a screen disappear’ and I noted the websites I was visiting most frequently during lockdown, like gov.ie to check for corona virus updates.

I spoke with my tutor at the time who recognised what I was doing as a type of ‘documentary embroidery’, as used by researchers Aviv Kruglanski and Vahida Ramujkic, which uses no previous planning. It encourages the sewer to ‘economise and abstract’ certain information. Consequently they follow a process of encrypting and ‘creating symbolic graphics’ when limiting details. In documentary embroidery, the slowness is considered an opportunity to engage with each other, and share ideas. I wanted to introduce this community aspect into what I was doing too, but it would mean having to compromise the ‘tech-free’ element of my exploration.

The Circles 1

By simply Googling ‘virtual sewing circles’, I discovered that there was an emergence of ‘digital stitch’ communities during lockdown, where many in-person groups from all over the world had gone online for the first time. Sewing circles on Meet-Up, were now adapting and embracing video calls as a way of keeping these communities alive during Covid-19. This opened up opportunities to join dozens of sewing circles all over the globe that would have not been accessible to me otherwise. Of course, there is always a risk involved when opening up to a wider, online audience, so for the Glasgow Virtual Stitch and Knit group, I went through a type of ‘vetting process’ before hand by answering questions to verify who I was and reduce the risk of attacks, like ‘Zoom Bombing’.

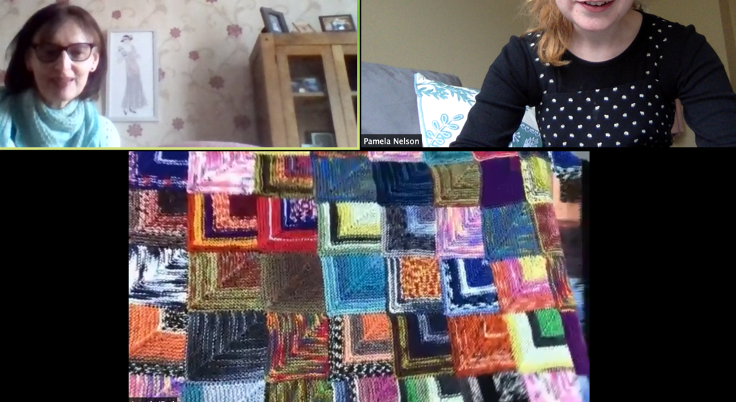

First, I was introduced to the members; Rachel*, had been working on a cross stitch piece, but explained that as she was getting older and her eyesight was deteriorating, therefore she would more often knit to wind-down. Emma* had recently suffered from a stroke and as a result had forgotten how to knit. She was taking the time to relearn the basics and was working on a patchwork blanket using an Icelandic wool that her son brought back from a trip last year. I told them a little about my sewing project too, and just by sharing what we were working on, we had already learned so much about each other that was not necessarily directly said. I don’t think any of us were too concerned about producing a ‘finished piece’, the common ‘thread’ here was the act of sewing/knitting had its own set of rewards.

We talked about how they had to adapt to new technologies to keep the circle going, like video calling over Zoom for example, which they had never used before. My general impression was that using this technology was a positive experience for them for the most part as it allowed them to reintroduce structure to their weeks by scheduling these online events. For me, being engaged in conversation and in the act of sewing simultaneously made me less aware of the screen as a barrier. I noticed that I was experiencing less ‘video call fatigue’ as I usually would. I decided to leave after an hour, put my needle and thread down and get some fresh air. I think it is really important to be aware of your own limits and take breaks accordingly when you are online.

The Circles 2

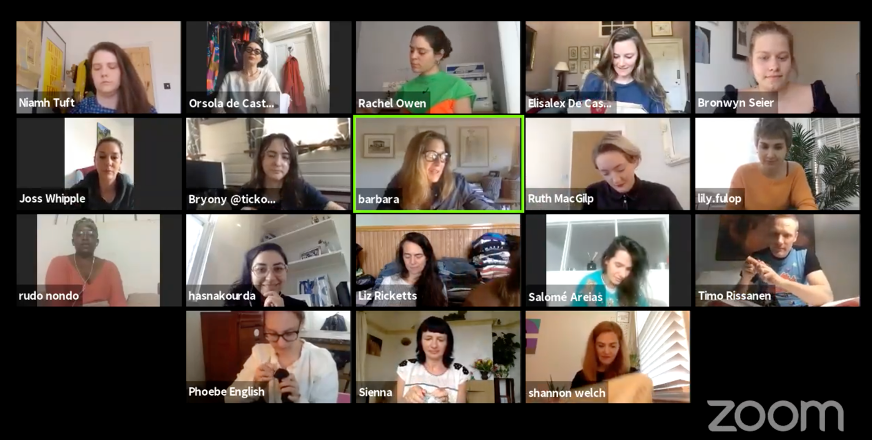

The Fashion Revolution hosted a virtual ‘Stitch and Bitch’ panel event with many fashion/textile revolutionaries from across the globe. This year, all in-person Fashion Revolution Week events were cancelled and held online instead. The main benefit of this was that they reached a far wider audience than possible if the events had taken place locally. Each of the panelists were working away on something; whether it was darning a pair of socks, mending a hole in an old denim jacket or picking lint balls off an Aran sweater. I streamed it and embroidered along with them too. I was beginning to notice how the physical engagement during these calls was counteracting the anxiety I often feel from being on video chats for long periods of time.

It was here that I became aware of the scale of the growing popularity of embroidery and mending during quarantine that was happening all across the globe. Throughout this global crisis, people seem to have turned to sewing as a way of maintaining their mental health. Often times, embroidery is used as a tool in prisons or in refugee centres as a way overcoming trauma. Since the outbreak of Covid-19, refugees in Direct Provision centres in Ireland have also been using sewing as a way of remaining somewhat autonomous during this time by making and selling face masks online. A participant shares words of wisdom passed down from her grandmother, who emphasised the importance of teaching her grandchildren to sew; ‘as a first instinct, we use our hands’.

The Circles 3: Hosting my own circle

I was eager to discuss these insights further with some of my old textile classmates and thought that a sewing circle would be the best format for that discussion. Looking to the book ’Draw it with your Eyes Closed’ for inspiration, I designed a ‘guided-meditation’ session, where the participants followed simple instructions; sew where you are living now, sew a journey that you frequently make, sew how many hours you average online per day, sew the number of video calls you make a week…etc. There were no strict rules or no pressure to complete every task, instead they could stitch the information or answers that were most important to them, or that resonated the most with their own personal stories and experiences of quarantine.

The end result of this sewing circle resembled a small collection of ‘maps’, each an abstract and symbolic representation of our current lives in relation to the technology we are using and the restrictions that currently in place. They felt like souvenirs or memories of that gathering, like a ticket stub from an event that you might hold onto as a memento. I realised that I was now engaging in the digital world in a way that was deliberate, mindful and had a physicality too. I was becoming more aware of being in two ‘spaces’ at once; conversing in a virtual space, while sewing brought me back into my own physical world.

Conclusion

Traditional methods of crafting, like embroidery, seem to reemerge for a number of reasons during times of crisis; whether that is as a coping mechanism, as a practical resource or as a method of storytelling/documentation. The strange thing about this re-emergence for me is the juxtaposition of the return of this craft through technology. The isolating nature of this crisis has left us all at home, some strongly relying on online communities for comfort and support, meaning that most of these groups, for now, exist virtually. The emergence of the ‘digital stitch’ community during Covid-19 makes me wonder that while we are in lockdown or if we should ever be again, will we ever truly be able to disconnect? Instead of interpreting ‘slowing down’ as being offline, we will just have to find ‘slower’ ways of being online? Could hand sewing and the world of ‘digital stitch’ allow us to stay connected with each other but also to our own minds and bodies?