When web developer Joel Galvez quit Facebook, he realized he had no accessible overview of events anymore – ‘newsletters and Instagram are just not the same, they give glimpses, but they don’t tell you what you could do this Saturday’. That’s why he started his project Public Data for Public Events (publicdata.events), a simple, low-tech, FLOSS solution, where you can curate your own calendar based on the event data that institutions made publicly accessible – all you need is their domain-name. And most importantly, all of this is completely open source and independent from closed platforms such as Facebook.

As we made our INC event data public to support Joel his project, we sat down with him to talk about his plans, how Public Data for Public Events works exactly and, of course, the politics behind it.

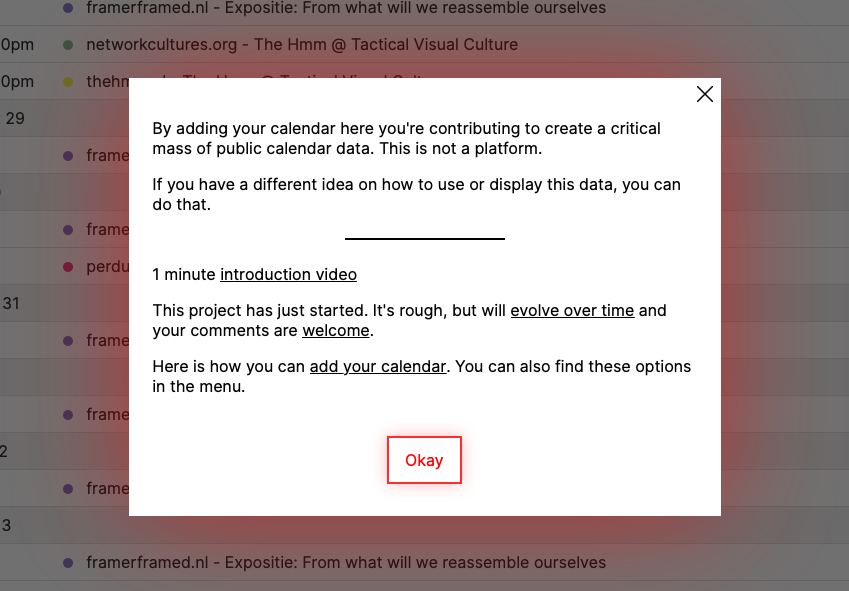

Pop-up on apocalendar.today, Joel his personal calendar.

Hey Joel! First things first. Why quit Facebook and not Instagram?

‘Haha, I know, I know. Facebook makes you feel weird. Instagram enters my life a little bit less. I’ll do it eventually. First things first; finish my calendar.’

Yes, tell us more about it. How does it work, exactly?

‘You could see it as a dumbed-down, special-case of the semantic web, perhaps. If the semantic web was an airplane, this is a bike without gears. All the event data is already out there, locked up in various websites of institutes that organize events. It’s not like we need to put more effort into writing it and publishing it for yet another platform. It just needs to be opened! That’s basically what I’m doing. Public Data Events exists out of three projects.’

Okay. Tell us more.

‘The first is getting a critical mass of theaters, venues and galleries to export their events in iCalendar format. This is the biggest challenge, because I have to convince them it’s worth it to pay their developers for a couple of hours work, to create an automatic export.’

What’s the second project?

‘To propose a standard way this calendar data is findable by only knowing the domain name of the theatre, venue or gallery. The dream is that a calendar-developer, like me, can think ‘Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam has public events – they probably have a public calendar, and then be able to find that calendar by only knowing their domain name (stedelijk.nl)’. Under the hood, from the domain, I could find the calendar through a link – which would be a simple text file, like this one.’

And the third?

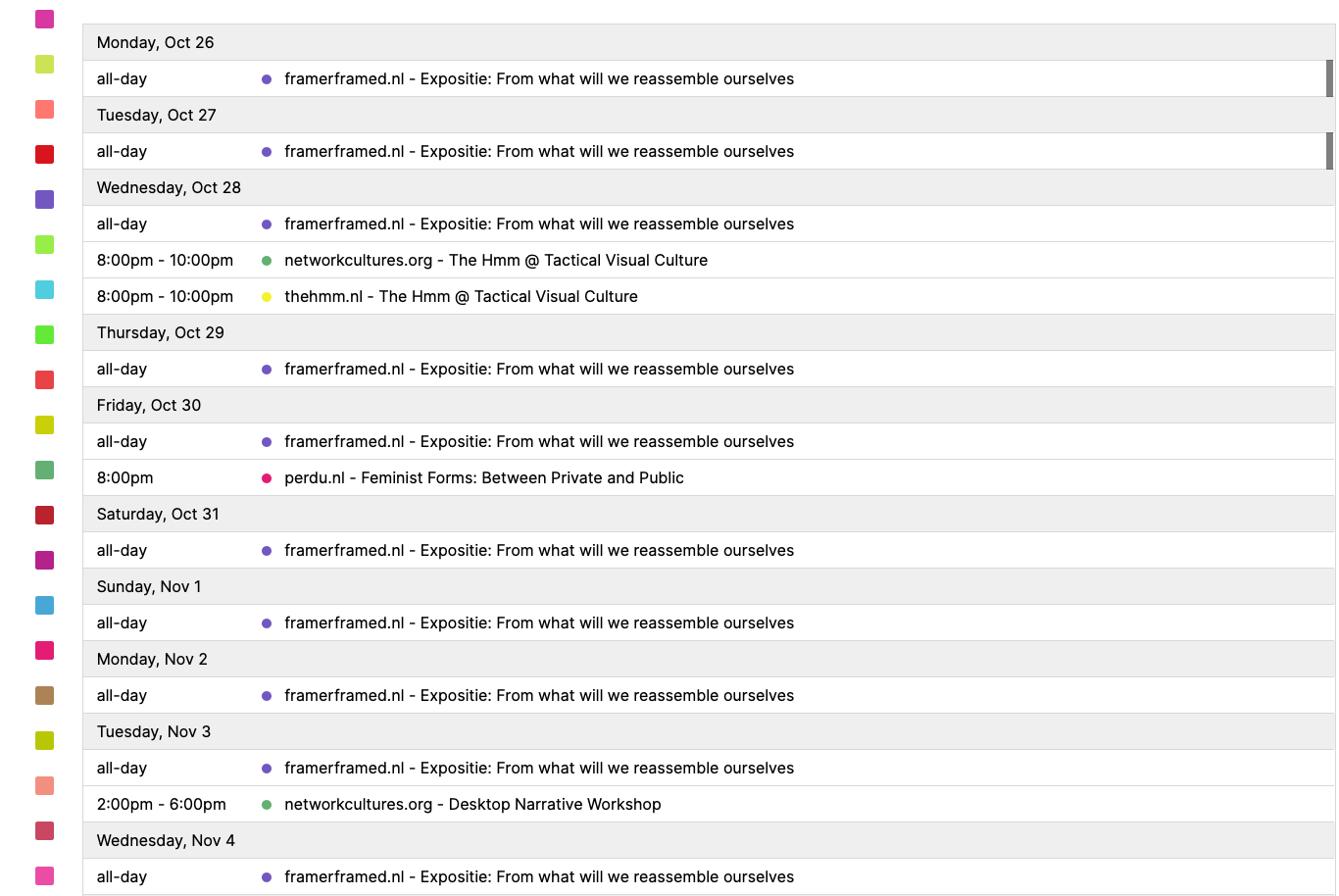

‘To make a working calendar using the data from the first two projects. My personal calendar is called apocalendar.today. It’s currently a boring calendar and I realize I need to make another one that looks more dazzling – a lot of people can’t see past the utilitarian nature of it.’

Can anyone make one?

‘Yes! The model I propose for the third project is just one proposal. Someone else might have a different idea – hopefully mine won’t be the only one. My proposal is based on federated personal ownership. You go to apocalendar.today, because you trust me. Brussels.fyi is run by Byrthe Lemmers is Brussels and you go there because you trust them. They have one calendar and the rest comes from my server, so they trust me to subscribe to my list. This way, if one of ‘my’ calendars get hacked, you can trace it back to me through a network of trust, and you can see it’s not Byrthe’s fault, for example. This model won’t work with 50.000 calendars of course, but hopefully the first two projects are independent enough for it to be possible to experiment with different models on top of this data in a collective manner.’

Does this work for events only?

‘In general, I like events as the basis for this project. It’s a very simple and tangible entity, unlike what ‘friend’ means with social media platforms, for example. My dream is that someone else will make a different calendar on top of this data, or maybe tie it together with some other date to create something completely different.’

And how about censorship. Could I organize an off the grid LHBTIQ+ event in Russia and put it on there safely?

‘You’re right. In its current form it’s impossible to combine distributed and restricted access at the same time. I hope I can get into a discussion with someone that is good at encryption and security about this soon. For now the focus is on it being entirely public.’

What about the other side of this – what if right extremists decide to create their own domain and share their events with the same technique?

‘It’s unavoidable. The question is how to react when this enters a more public setting, I think. When it comes to public discussion, I wonder if the domain-based trust model could help distributing the work of classification and moderation. You might judge something from ‘dodgy-vpn.com’ differently than a response from ‘that-particular-organization.com’. Let’s say we have a threaded discussion with comments from both of these sources. How to handle the difference in trust within the same discussion could then be a public and collective design project. In the platform/data-silo there are no domains, so some nuance on trust is also lost. It’s a shame, I think. I love domain names – I love buying domain names. Anyway, I haven’t discussed this very much with others – so this project is a way to pose the question if domains could maybe help.’

Let’s get away from the hypothetical for now. What kind of institutes would be interested in this now?

‘Right now it’s mostly publicly funded art spaces. It’s a good way to start, they are already used to participating in projects like these and usually understand the added value straight away, and they are close to my heart. Later down the road it could be interesting for any organisation, perhaps.’

How would you balance publicly funded and commercial organisations?

‘Spending another 500 bucks to make their data public is something a lot of (commercial) companies don’t want to do, because there is not much infrastructure for using it, but more importantly, it does not benefit them directly. It might even harm them because someone else could build a platform with their data. Plus it’s harder to make money with advertising. It’s a situation where self interest doesn’t work. My plan is to get the attention of public institutions that could fund those extra 500 bucks companies would need. It’s maybe easier to achieve this if the organizations are already publicly funded.’

‘To give you an example: Kidsproof.nl is a great site for finding stuff to do with my 5 year old son. If theirs and Stedelijk’s calendar data was available together, I could plan my weekend easier. That combination has value to me. Stedelijk does export their events to Kidsproof. OT301 does nice stuff for kids too, but their events are not on Kidsproof. With open data I could make this combination myself. I could ‘fork’ kidsproof, and make my own version that includes OT301. If this takes off, there will be some danger that someone with a lot of resources makes a much better calendar aggregation service but tweaks it to their purposes and ruins things for those with less resources (such as the EEE approach Microsoft is known for). So far it’s just a hobby project for me, but it’s still good to be mentally prepared, perhaps.’

‘To answer your question. It’s not about a balance between commercial and noncommercial – both should use this. It’s just easier to start with publicly funded organisations, since this project needs to be funded with public money eventually, somehow.’

apocalandar.today – casually notice the INC events on there as well

What’s your personal motivation for this project?

‘I spent the last 10 years trying to make new things in a practice close to conceptualism, which started to feel a bit introspective – too much self referencing within the traditional arts and into the medium itself. This is my attempt to try something different. I wanted to try and do something more political in a way that didn’t feel forced to me, so I stayed close to the heart. Perhaps, it’s partly a response to the detachment created by COVID and the transient nature of being an independent without a boss or employees as well – I want to go out more. I hope this will become a long term thing. I’ve been getting very rewarding responses on this project.’

What kind of responses?

‘Most are excited for the potential hope to not be dependent on Facebook anymore. But not everyone gets it, however. I was on the phone with someone who said ‘why are you doing this, when there is Facebook?’. If that person realizes the benefits of open data, it would feel like I’ve achieved something. It doesn’t take that much effort, just a moment of synchronized dancing. This needs to exist.’

Why does the world need this?

‘In an ideal dream scenario: let’s say De Balie decides that they want to propose using hashtags for the events, but Spui 25 doesn’t want that. We could have a discussion about whether or not this is a good idea and how it should be implemented. It’s about that discussion – being able to define it ourselves, instead of having to deal with whatever platforms decide behind closed doors. We could make several variants, to see what sticks. It sounds very utopian, but it’s not that far fetched, since the data already exists.’

By the way, could non-programmers create a calendar too?

‘Yes! It will take someone who isn’t a programmer a bit longer, but the plan is to automate the process as much as possible and present a clear guide. You can ‘fork’ my calendar, change the list and all the description texts, without being a programmer.’

Where do you see this going in the future?

‘Every organization added to this project that uses an automatic export is adding to a continuous stream of public data. When they fill their website, they automatically fill my calendar. I’ll keep trying to add these sources the coming year. It won’t be a superfast process, but once it’s added, it’s automatic. If I have collected enough data, it will be easy to say “look here to stay updated”, but that will take some time. Like I said, my hope is to find some funding soon, to be able to give some money to these organizations to speed up the process of opening up the data. That would make it easier to say ‘look developers, here is nice public data to experiment with’. If this idea really takes off, I’ll need a solid non-profit organization underneath it too, for support and to maintain its independence.’

We’re sure you’ll pull it off!

‘It’s still early in the project. It could happen that someone says ‘this won’t work because of X’, or worse, ‘this already exists’. This hasn’t happened yet. But if it does, I hope someone tells me as soon as possible.’

Joel Galvez has been making websites since 1996. He never felt happy about the distinction between programming and design, as things tend to get predictable. He studied Informatics in Sweden and Graphic Design in Denmark and in Amsterdam at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie.