Here’s a conversation starter: “What do you do?” “I research conspiracy theories.” This response is usually met with varied forms of excitement and curiosity: “Oh, sick, I love conspiracy theories!”, “Like what, 9/11? You know, I think it was an inside job”, “You know, I think this corona stuff is made up by [insert global superpower/anti-Semitic trope/alien conspiracy] to control us!!!1”.

Let’s get straight, I understand that “good”, or at least legitimized, knowledge is not a neutral notion. I also understand that conspiracy theories are, in the end, alternative ways of processing information in an increasingly networked age, “a way of making links in the combined sense of discovering as well as creating”[1]

It might be comforting to think that the shadowy figures that populate the more unpleasant corners of the internet, as well as your aunt on Facebook, are cretins who genuinely believe the narratives they spout to their audience of galaxy brains. It helps recalibrate our own position as sane, thinking, intelligent citizens and identifies a scapegoat in a nebulous uneducated, media-illiterate class that seemingly dispenses with science and logic.

What some of these conspiracists understand better than most is that this game is not one of winning people’s minds, but their hearts. All clichés aside, appealing to users’ logic with sound arguments and facts simply doesn’t do the trick anymore. You have to be able to generate clicks.

Why Are Conspiracy Theorists So Obsessed with Collagen?

Much like all entrepreneurs, conspiracy theorists need an actual product to sell, something that can finance their efforts to propagate arcane stories about “evil lizard people” and the like. And while they do traffic in conspiracies, they often must find other things to capitalize, especially in a precarious platform landscape, where demonetization and deplatforming are lurking around the corner.

RedPill Living: QAnon truther Dustin Nemos’ eshop.

From Dauntless Dialogue on YouTube.

Rebecca Lewis has previously pointed out that political content creators use tactics linked to lifestyle influencers, and build their brand identity, connect with their audience, and market their (political) ideas in similar ways[2]. It’s not merely the shadowy Algorithm, which radicalizes the masses, but the networked potential and influence dynamics of the platform itself, as well as the ability it affords to capitalize on extant demand.

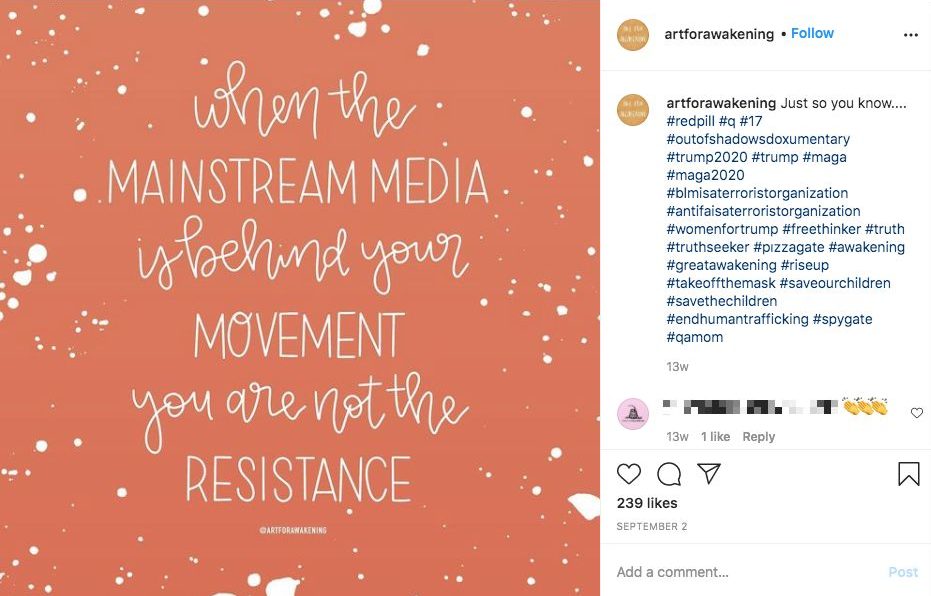

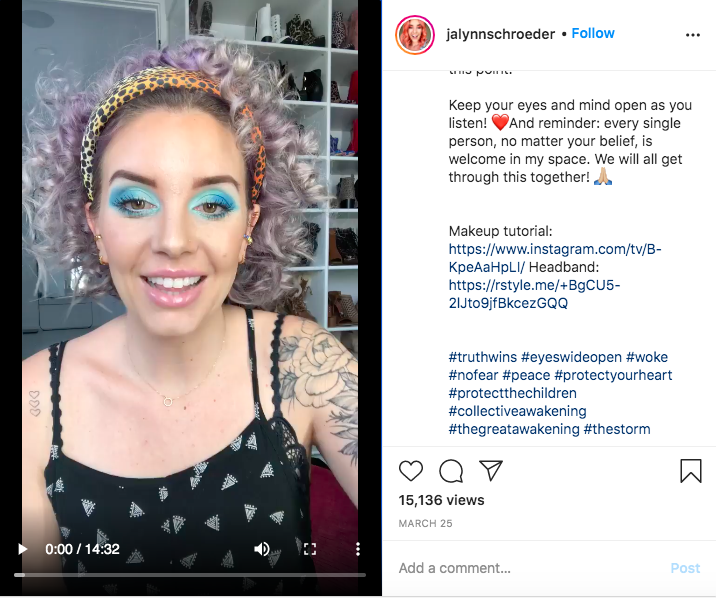

It isn’t especially surprising that a number of lifestyle and wellness influencers have also realized this and begun repackaging and seamlessly integrating QAnon and pro-Trump hashtags into their saccharine Insta-aesthetics. The alternative wellness industry (think essential oils and healing crystals), already suspicious of pharmaceutical companies and mainstream talking points around health and dieting, serves as an ideal mouthpiece for such content.

The “Live Laugh Love” aesthetics of QAnon.

Who said makeup tutorials and QAnon propaganda didn’t go together?

It makes sense that conspiracy theories become more insidious when they linger behind more “wholesome” aesthetics or commendable causes, like wellness and spirituality. Take Maryam Henein, for instance: the director of an award-winning documentary Vanishing of the Bees, about bee preservation, is also a prolific COVID-19 conspiracy peddler.

This is also the case when it comes to the supposed anti-establishment cadence of conspiracism. In the Netherlands, a plethora of influencers and celebrities have parroted the talking points of conspiracy group Viruswaarheid, calling on people to: “get the government back under control”. Viruswaarheid has also received support from the right-wing FvD’s embattled leader Thierry Baudet.

Critiquing Critique

This is the caveat of basing one’s politics around resisting a loosely defined status quo. Georgio Agamben’s op-eds from earlier this year excoriating the state of exception imposed by governments and the belief that COVID-19 was no more serious a threat than the common flu curiously mirror the theories emerging from more reactionary corners of the web. Indeed, refusal to comply with the imposed measures is often framed in terms of resisting authority.

Back in 2004, Bruno Latour [Author disclaimer: As a grad student in an STS-heavy media studies program, I am legally obliged to quote Latour] wrote that the spirit of critical thinking and healthy doubt has been deformed by conspiracists[3]. Inhabiting an increasingly complex networked landscape, and grappling with the lessening importance of our decisions, also means that we are primed to look for connections and eager to make sense of things[4]. Conspiracy theorists might be the most eager of all.

I do consider myself a person with decent critical thinking abilities, but I also find myself torn between the imperative to question constructs like objectivity [Author disclaimer: As a grad student in the humanities, I am also legally obliged to reject grand narratives] and my contempt for simplistic explanations for complex, systemic issues. Conspiracy theories, for all their convolutedness, are the latter, as they generally are mutations of preexisting fears, anxieties, and moral panics, things which easily lend themselves to appropriation by conspiracy theorists. As Marc Tuters and Peter Knight explain in The Conversation, “[c]onspiracy theorists usually have a complete worldview, through which they interpret new information and events, to fit their existing theory”.

Despite what Russell Muirhead and Nancy L. Rosenblum recently diagnosed as “conspiracy without the theory”, conspiracy supporters, including corona-deniers, often instrumentalize scientism just as often as their opponents do, albeit in different ways, likely because they are aware of its authoritative appeal. Despite their apparent critique of the “status quo”, many of these conspiracists still invoke authority in order to consolidate their credibility, from citing “experts” to masquerading as experts themselves.

What makes this penchant for critique, as well as the appeal to authority, even more interesting is its pairing with faith and religiously inflected spirituality. Born-again Christian and Q interpreter Praying Medic, whose real name is David Hayes, embodies this apparent contradiction. A prolific author of books about spiritual healing, he has more recently veered into Q and Covid-19 conspiracy territory[5].

Apocalyptic language and skepticism seem to not go well together, but they might actually explain how conspiratorial narratives like QAnon have managed to mobilize and sustain such a diverse following, uniting 4chan denizens following digital “crumbs” with mommy bloggers fearing for the safety of their children.

Teh Internet Is Serious Business

Researchers conducting work at the intersections of online subcultures, trolling, and bigotry have pointed out that ambivalence is a feature of this volatile landscape. This landscape bears more of a resemblance to the anarchic and playful cyberspace of the 90s than the post-2010s platformized web, where the offline and online are increasingly converging around the performance of a stable, quantifiable, and datafied identity. Anonymous image boards have cultivated a reputation as spaces where meaning is produced through the carnivalesque performance of identity (via linguistic signifiers rather than other conventional identity markers) and the mockery of all things serious. This ludic spirit has in more recent years been transformed into, well, a cesspool of bigotry; and, in the face of the supposed political dominance of technocratic liberalism, the memetic turn of the 2010s can be understood as a reactionary attempt towards “metapolitics”, the (ironically) Gramscian project of transposing politics in the domain of culture.

All of this has been widely discussed and written about, of course, but it bears repeating. For the past five or so years, journalists and commentators have been caught up in the vortex of the reactionary right and its discontents—fringe internet fora and the conspiracy theories that these have spawned—often while lacking the conceptual tools to discuss these phenomena. To explain that irony and ambivalence are fundamental features of these discourses is not to take them lightly, but is crucial in order to understand them.

And now the million-dollar question: what happens when there’s money to be made?

(Former?) alt-right darling, Laura Southern, was recently the subject of a profile in The Atlantic, which, besides painting a rather grim (with a dash of Schadenfreude) image of the way this political space treats its women, has also confirmed the suspicion of many: genuine belief in extreme ideas isn’t actually a prerequisite to publicly espouse them. In fact, we might argue that being a woman, a person of color, an LGBTQI+ individual with reactionary ideas offers an easier pathway to attention and therefore speaking engagements, and monetization opportunities; take a look at Milo Yiannopoulos (before his dramatic fall from alt-right grace).

If these reactionary ideas can easily be combined with latent societal fears and anxieties—the perfect raw material for the creation and dissemination of conspiracy theories—,well, even better!

But weren’t conspiracy theories supposed to be fringe, marginal, and decidedly unmainstream?

The Platformization of Conspiracy Production(?)

We are arguably living through an era in which leisure is being absorbed by the neoliberal imperative of productivity. Before the “influencer’ was a venerable career path, she was an average person mediating between companies and audiences in a more or less hobbyistic manner. As the perception of the influencer is becoming increasingly imbued with inflections of celebrity, and conventional professions burdened with demands of self-branding, we are now observing figures like the journalist-as-influencer, the academic-as-influencer, the meme producer (or poacher)-as-influencer. Why not, then, the conspiracy theorist as influencer?

It is indeed a bit surprising that the figures which emerged from the murky waters of anonymous imageboard culture are building their profiles as (soooort of) legitimate entrepreneurs. Pizzagate, QAnon, and the Epstein-didn’t-kill-himself narrative were initially based on the anonymous crowdsourcing and crumb-collection of 4chan. Here a marked separation of the “real” from the online is encouraged, and the entrepreneurial spirit cultivated by mainstream platforms becomes a target of ridicule. But conspiracy entrepreneurs, like Dustin Nemos, who was recently interviewed by CBS News as one of the “leaders” of QAnon (itself an oxymoron, if we look at the non-hierarchical vernacular spaces from which QAnon originates), not only denounce anonymity but also, by monetizing their content, the ostensibly idealistic premises that are still venerated in these domains.

Like so many other things, including sociality, labor, and cultural production, it is unsurprising that the dissemination of conspiracies might also become subsumed into the logic of what Anne Helmond has called platformization, or the “rise of the platform as the dominant infrastructural and economic model of the social web”[6].

As we are beginning to see with other kinds of celebrity, the more “established”, old-school conspiracy entrepreneurs, like David Icke (who has been banned from Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter), are increasingly being replaced by a new crop of conspiracy influencers, who have found a precarious home on YouTube, Twitter, and Instagram (as well as alt-right-friendly platforms, like Bitchute). While their viewership is generally smaller than that of the alt-right celebrities Lewis writes about, they mimic their techniques of influence, having established an alternative (facts?) media ecology, where conventional influencer practices, such as collaborations, brand deals, promotional codes, subscriptions, memberships, and merchandise, provide opportunities for the monetization of controversial content. What is sold, beyond snake oil, is an overarching lifestyle.

Of course, these creators, whether it’s the “old-school” Q interpreters or the pastel-tinted lifestyle bloggers, are aware of the dangers of deplatforming, which is why their branding takes on the added urgency of having to adapt to perceived censorship, introducing new hashtags, as well as grammatical and spelling mistakes in an effort to obfuscate the true meaning behind their hashtags and posts.

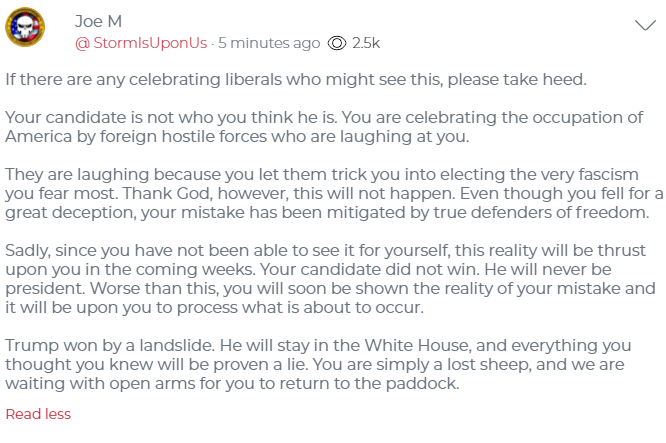

If we assume that these millennial and Gen Z conspiracy entrepreneurs do not, literally and figuratively, buy what they sell, is it only profit that motivates their peddling of outlandish theories and dicey remedies? What about the ludic, mischievous essence that undergirds the spaces where such theories often circulate? Of course, monetization and name-making betray this. And QAnon buffs having a meltdown about their supreme leader failing to sweep this election implies that not everything is a joke, after all.

Joe M, noted Q influencer, handling Trump’s loss extremely well.

On the other hand, the dissemination of misinformation is facilitated by hordes of bots, meme factories[7] or digital armies[8], all of which indicate a standardization and a certain professionalization, in line with what we’ve been seeing in other forms of invisible, “free”, and immaterial labor performed online. Platforms are now more intensely cracking down on disinformation, but this response has only come after influencers on Instagram and YouTube amassed thousands of followers by posting conspiracist content.

Does this signal the capitulation of previously untouched grounds to the logics of platformization, professionalization, and expropriation of collectively produced vernacular creativity? And if so, does this mean that the last major frontier of the playful, irreverent, and unmonetizable “old internet” is a white supremacist-infested swamp?

There is something profoundly depressing about that.

References

[1]Jodi Dean. Aliens in America: Conspiracy Cultures from Outerspace to Cyberspace. Cornell University Press, 1998, p. 143.

[2]span style=”font-weight: 400;”>Rebecca Lewis. “Alternative Influence: Broadcasting the Reactionary Right on YouTube.’ Data & Society, 2018, https://datasociety.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/DS_Alternative_Influence.pdf.

[3] Bruno Latour. “Has Critique Ran out of Steam?” Critical Inquiry, 30, no. 2, Winter 2004.

[4]Dean, Aliens in America.

[5]The “medic” in his moniker might imply medical training and incur a legitimacy, particularly regarding his coronavirus-related videos, but Hayes is actually a paramedic.

[6]Anne Helmond.“The Platformization of the Web: Making Web Data Platform Ready.” Social Media + Society, July 2015, https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115603080.

[7]Crystal Abidin. “Meme factory cultures and content pivoting in Singapore and Malaysia during COVID-19”. HKS Misinformation Review, July 15 2020, https://misinforeview.hks.harvard.edu/article/meme-factory-cultures-and-content-pivoting-in-singapore-and-malaysia-during-covid-19/.

[8] Estrella Gualda Caballero. “Social network analysis, social big data and conspiracy theories”. Routledge Handbook of Conspiracy Theories, Routledge, 2020, pp. 135-147.