Who remembers the first time they heard the term ‘Girl Boss?’ For most, it was around the time founder of the fashion brand Nasty Gal, Sophia Amoruso, published her autobiography ‘#GirlBoss’ in 2014. Since then, the term has grown in popularity to the extreme, creating its own aspirational ‘category’ of woman, archetypal image, and countless spin-off self-help guides, websites, YouTube channels, podcasts, ‘influencers,’ a Netflix series, merchandise, seminars and courses – to name but a handful of #GirlBoss lifestyle commodities.

Amoruso’s #GirlBoss book covers her path growing a multi-million-dollar company, Nasty Gal, out of an eBay vintage-resell store. It tells/sells an authenticity story of a woman going against the grain (including shoplifting, which “saved her life”) in the face of changing media, technologies, and social circumstances. Amoruso’s mantra is “Life is short. Don’t be lazy.” It captures the zeitgeist of millennial women ‘thinking divergent,’ ‘being fearless,’ and ‘staying game strong,’ to pursue and monetise their passions. Shortly after the book’s release, marketeers caught onto the sellability of the Girl Boss ideal, which quickly spread into visual culture. Seven years later, the Girl Boss continues to linger on social media platforms, but who is she now? What does she indicate about real contemporary setbacks? And how does she fit into today’s discourses? First, let’s begin with an explanation of what exactly is a ‘Girl Boss.’

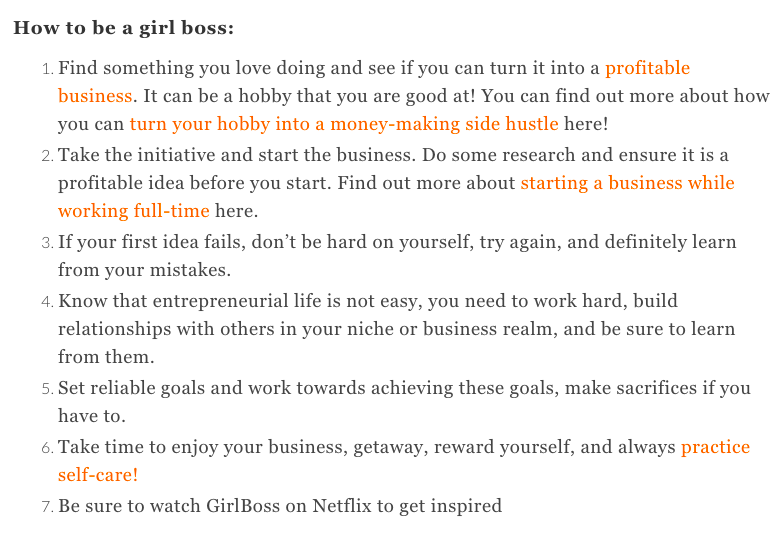

How to Construct a Girl Boss

The Girl Boss is a boss, but not in the traditional sense. The Girl Boss does not perpetuate the image of a middle-aged CEO dressed in a suit. After all, that image is unattainable, being reserved to only one gender identity. The Girl Boss might wear a suit, but she will make it playful and pop-coloured. It will be a statement. For a magazine feature, she will pose with her arms crossed, camera aimed from below, and shot against a skyscraper backdrop. Then, she will gush over her children in the interview and reveal her favourite beauty products and fitness routines. She may be the owner of a fast fashion brand that mistreats garment workers in Bangladesh, but she will sell you a banging t-shirt with ‘The Future is Female” printed across it.

Since the Girl Boss has had to pave her way, having been overlooked or underappreciated by fellow (male) entrepreneurs, her story hinges on self-determination and unparalleled work ethic (what Amoruso calls “sweat equity.”) Having ‘made it’ despite no end of obstacles, the Girl Boss now has it all; a successful business, incredible discipline, an army of assistants and interns, a loyal squad of girlfriends, and a wardrobe of effortlessly chic fashion to go with it.

.

.

The enduring appeal of the Girl Boss lies in her ability to succeed as a business owner whilst retaining traditionally ‘feminine’ characteristics. She’s a killer in the boardroom, and never has bags under her eyes. The Girl Boss elevates herself beyond the need to act like ‘one of the boys.’ She is 100% herself, and unapologetically so. A girl’s girl in a world of businessmen with all the accessories to prove her success: an It bag, red-soled stilettos, and a bad-ass sports car to zoom away in.

Not only has the Girl Boss achieved financial independence; she hasn’t given anything up to achieve it. The Girl Boss promise is that great monetary success is possible and can be attained without compromise. In ‘having it all’, the Girl Boss embodies a post-feminist dream of equal-opportunity access to educational resources, mentoring, start-up capital, and financial security. Not just security – abundance. In this dream, no patriarchal structures are holding her back. Her life, imagined collectively on social media platforms through pastel images and energetic videos, is not a humble brag. In this rendering, her life also does not include dealing with workplace misogyny, harassment, and she does not have to experience ongoing derogatory treatment. There are no pay gaps, no sexism or racism in the workplace. There are no gatekeepers. Only a free market, which any woman can circumnavigate via hard work. “Life is short. Don’t be lazy.” The Girl Boss is a queen of her kingdom, and nothing can snatch her crown.

The Girl Boss makes no apologies for her femininity because her femininity is an asset. It is a crucial ingredient in the recipe of how to make a Girl Boss; the construction of a business owner who refuses to change herself to blend into a male-dominated field. In this sense, the Girl Boss challenges the preconceived notions of what success looks like. Emerging into the world of money and power, the Girl Boss brings the promise of change with her. Her mere presence in this space represents all women everywhere, paving the way for others to follow, and displaying that it is possible to reach such levels of success as a woman. The Girl Boss is the poster child for equal opportunity. However, behind her dazzling facade still lies a reinforcement of patriarchal archetypes that restrict women more than they empower them. It calls to question: Who actually benefits from the presence and prominence of the Girl Boss? Scholar Mary Beard offers some food for thought, suggesting that “We have to be more reflective about what power is, what it is for, and how it is measured.”[1]

.

.

TikTok, Instagram, and Pinterest overflow with Girl Boss content. Here, you will find luxurious shoes and bags, important-looking paperwork, beautiful pens, extravagant sunglasses, fun on rooftops, glamorous cars, champagne flutes, and flawless manicures, all sewn together with inspirational quotes about perseverance. Girl Boss social media grids are sleek, colour-coded, and establish an alluring image of independence and wealth. These images of playful expensive nail art and impractical-but-‘boss’ heels run counter to the content of the male ‘hustler’ entrepreneur – equally ubiquitous on social media platforms.

Despite the now household-ness of the Girl Boss ideal, the majority of the entrepreneurial lifestyles promoted and venerated across social media still minorly cater to women. The aforementioned self-identifying ‘hustlers’ mainly identify as male and are generally ignorant towards misogyny in the world of business – which it doesn’t take long to notice when perusing their sub-Reddit homes such as /r/entrepreneur, /r/investing, /r/CareerSuccess, /r/startups, or /r/growmybusiness. Hustlers are not interested in addressing the inequalities that affect access to education, funding, and mentorship. They’re interested in making money. What lingers, no matter the sub, is a pervasive association between positions of power and masculinity. One that endures as a signifier to the past when the subjugation of women made it impossible for them to pursue independent careers or make self-governing decisions.

The Construct Crumbles

It comes as no surprise that many journalists and theorists link the term ‘Girl Boss’ with the infantilisation of women. The ‘Girl Boss’ label categorises the successes of women as separate from, and inferior to, the achievements of their male counterparts. Since the glory days of Sophia Amoruso’s brand (circa 2010-2015), the popularisation of Girl Boss wavered, and critical engagements with the concept weakened its persuasive powers. The year 2020 saw many Girl Bosses resign over allegations of toxic workplace cultures. Still, #GirlBoss tags persist on social media and millions of users interact with Girl Boss content every day, seeking to personify the (unattainable) ideal of the Girl Boss that presents itself as something within reach. After all, being perceived as a success is just as important as success itself; and perhaps the aesthetics of life in big business alone are more compelling than the reality of pursuing such a career. More on this in the next section.

The Girl Boss imaginary romanticises the idea of wealth but does not take into account the methods by which it may be acquired. In this sense, the Girl Boss is a neoliberal pawn; an affluent individual whose inspiring story supposedly proves the accessibility of success and demonstrates that opportunities wait for anyone willing to work hard enough. Don’t spend too much time thinking about what business the Girl Boss owns, how it operates, or who may be affected by it.

“Simply incorporating women into positions of power does not guarantee equality or justice in the larger sense. We always seem prime to celebrate individual advancements of black people, people of colour, women, without taking into consideration it might simply mean that previously marginalised individuals have been recruited to guarantee a more efficient operation of oppressive systems.” – Angela Davis

Reflecting Angela Davis’ expanded contemplation; would it be sensible when examining the Girl Boss figure to consider a more communal approach instead of accepting another archetype representative of individual success? How else might we reach a collective redefinition of ideas of power and influence? This is not a proposal that seeing women in business is a setback for women everywhere. On the contrary, it is necessary to elevate women’s voices and provide increased access to positions of power. However, that in itself does not guarantee structural changes in the workplace, or the conduct of influential bodies of power. Ruby Staley writes: “When female CEOs and managers mimic the behaviour of the archetypal male boss, the patriarchal barriers placed in front of women in the world of work remain the same – they aren’t deconstructed, instead, they’re reinforced.”[2]

The Girl Boss facade of glamour and empowerment might be exciting and motivating to some aspiring women in business, but the prominence of this figure does not automatically challenge expectations, nor does it change the fabric of economic inequalities. Here, we also encounter the danger of tokenism; women and marginalised people are regularly exploited as tokens of diversity in conglomerates that could not care less about truthful representation, nor more equal access to opportunities and professional development. Women deserve more than a pity promotion motivated by pressure to meet a diversity quota.

What Comes Next?

Girl Boss and hustle cultures share many characteristics. For one, they refuse to acknowledge wider contexts of individual success stories. They both thrive on social media platforms where inspiring imagery and self-help tips taken out of context convey a message of an unhealthy dependence on work and quantifiable achievement. Both versions love easily digestible images and use short videos that entice users with promises of financial independence and lives of luxury. The more one encounters this kind of content, the more likely they are to start seeing their employment status as a definer of self-worth and identity. I fell victim to this trap when diving into online Girl Boss culture. Even though I lack the aspiration to be a business owner or a millionaire, I did catch myself feeling envious of the status enjoyed by these figures. Like many people, I too long for a life free from financial worries, unrestricted by the high prices of some comforts. It did provoke me to think… If I bit the bullet and went corporate, maybe it would be worth it? If I started to seek out a highly paid job, maybe I would be happier?

What Girl Boss culture has never really acknowledged is that the very incident of becoming a CEO might not automatically lead to satisfaction. Juliette O’Brien states: “It’s not just that hustle culture and productivity obsessions are exhausting, incurious, and self-aggrandizing. It’s that, on their own, they can offer an anemic, superficial, and tedious experience of life.”[3] In an ironic turn of events, O’Brien’s critique was published by none other than GirlBoss.com, a networking platform Amoruso founded in 2017, and abandoned two years later. It seems as though through its evolution over the past few years, GirlBoss.com’s online content – created by Amoruso and others – has gradually increased its nuance around issues like toxic productivity, whilst its male-counterpart ‘hustle culture’ continues to hold strong with the workaholic mantra of doing “whatever it takes.”

The destabilising ripple effect of the COVID-19 pandemic marks a seismic shift in relationship to work. For one, it makes start-ups, side hustles and passive income more desirable and marketable. Anything to stop feeling threatened and endangered by an unpredictable economy and unstable employment. Some Girl Bosses claim a pandemic is a prime time to set up a business. These calls only multiply existing pressures to perform productivity, monetise interests, and invest whatever time and money you might have left into new sources of stress and anxiety. Instead, let’s follow Davis’ lead and focus on how oppressive systems dictate and demand these unattainable standards.

Plenty of work remains to be done about improving the societal positions of women within self-employment, labour, business, kinship and family. It might not be the kind of work the Girl Boss undertakes. Today’s online activity needs to shift in a new direction, away from the mythologisation of an egocentric figure and their individual successes in a “man’s world.” In recent years, there is a tendency to provide platforms to marginalised voices and to consider the bigger picture of intersections between labour, gender, race and class. Mobilisation via the online is another way to shift away from the hustle narrative, instead offering mutual support and resources to those interested in business and ethics. These gatherings can and should include users who resonate(d) with the Girl Boss narrative. Pink typography is not all bad; it might encourage users to dream and speculate about a future where gender does not dictate access to wealth and power. However, it is not sufficient, and the aesthetics of the online Girl Boss are much more likely to mask the impossibilities of standards they propose, instead of debunking them.

References

[1] Mary Beard, Women in Power, https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v39/n06/mary-beard/women-in-power

[2] Ruby Staley, Thank God We’re Finally Moving Past Girl Boss Culture, https://fashionjournal.com.au/life/thank-god-were-finally-moving-past-girl-boss-culture/

[3] Juliette O’Brien, Is Hustle Culture Actually Hurting Us?, https://www.girlboss.com/read/productivity-culture