Growing up, my friend had a Nintendo Entertainment System knock-off called Pegasus. I think it was only sold in Eastern Europe in the 1990s. I spent a few summers in her attic, playing a variety of side-scrolling and vertical-scrolling pixelated games. It was fun to see each other get better at different levels and challenges, but we never took it seriously and would often move on to other ways of filling our lazy summer days. Thinking back, video games were a nice addition to my childhood, but they did not leave a lasting impression.

Then I went to university and met peers who considered video games their passion. I began to understand this fascination; you get attached to certain characters, enjoy impactful art styles and soundscapes, and ride the adrenaline high of in-game combat. Over time, I began to enjoy video games for those reasons too. But I also wondered about an alternative to the narrative-driven, action-packed genre that continues to dominate the industry.

I bought my first console in 2018. I chose the Nintendo Switch; it was compact, versatile, and more approachable than other consoles, which continue to be surrounded by valorising discourse. I wasn’t interested in discussing which console might be the best. I just wanted to have a good time using the one I had picked. Enter Animal Crossing: New Horizons, which turns one year old this week. I got New Horizons in April 2020 as a birthday gift, and haven’t stopped playing it since.

My “Animal Crossing: New Horizons” loading screen (2020).

For the uninitiated, Animal Crossing: New Horizons is the fifth edition of Nintendo’s Animal Crossing series. It is a real-time simulation game in which players inhabit, customise and maintain a town also populated by a selection of anthropomorphic animal neighbours. The game does not have a clear objective or a skill improvement system. You spend your time collecting fruit and seashells, fishing, catching bugs, gathering fossils, and crafting items from materials you harvest. I understand that this type of gameplay and aesthetic may not be for everyone. I have to admit that when I first saw the promotional materials for New Horizons, I didn’t think it would be the type of game I would enjoy (too cutesy, too mundane, too surface-level?). I was wrong.

New horizons, new perspectives

Animal Crossing: New Horizons is the pinnacle of slow-paced gameplay. There is no way to ‘binge’ it, reach an ending or speed up in-game processes (although hackers did make some useful changes many players wanted to see from Nintendo’s updates). What you see is what you get. When you collect all your fruit, you have to wait a few real-life days to harvest it again. There are only a few items sold in your island’s shop each day, so if you can’t find something, you have to wait until it becomes available (or trade with another ACNH player using the online play feature; more on that later). New Horizons requires you to be patient while you make small improvements to your island, and contemplate the daily flow of your life there.

Thanks to the relaxed pace of the game, and the open-ended interpretation of its goals and purpose, players gain satisfaction from completing mundane tasks. I take great pleasure in cross-pollinating my flowers, picking up weeds and branches, and replanting trees and shrubs to customise the look of my island. There is a rituality in these tasks, a silent significance in the way I pay attention to this virtual space. Game designer Gabby DaRienzo calls it tend-and-befriend mechanics.[1] Instead of the fight-or-flight response many fast-paced video games trigger in players, this type of game instead operates on maintenance and relationship-building. The island is yours to beautify and customise. You talk to your neighbours, add a nice bench to your park, and craft items for your home. Life is good. At a time of heightened unpredictability, having a virtual space that is both unable and unwilling to catch you off-guard brings a well-deserved sense of safety.

The opening of my island’s campsite.

I have to admit I’ve grown quite attached to villagers who live on my island. During the many months of solitary isolation in the spring and summer of 2020, befriending the animals in New Horizons brought me an unparalleled level of tranquility and joy. And now, having somewhat grown used to the unpredictability and brutality of my COVID-19 reality and all of its political, social and cultural complications, I continue to seek a sense of security in New Horizons. Last year, art critic Gabrielle de la Puente shared her experience of the game, identifying it as one of the few sources of joy and repose in lockdown. I wonder if Gabrielle still plays New Horizons, and how her relationship with the game changed.

The idea of safety has been on my mind a lot in recent months. What do I need to feel safe? A few things come to mind: shelter, access to food, water, a support system of family and friends. Then there are needs like access to medical care (made more complicated while living abroad without proper health insurance), financial security, and, unfortunately, physical distance from others. In the tensest moments of the pandemic, playing New Horizons remained one of the very few activities I identified as wholly ‘safe.’ I did not have to ascertain the proportions between risk and reward; I could just log on and feel at ease. My friends and I would visit each other’s islands and find comfort in this unique togetherness.

In-game socialising

Our chibi in-game selves were allowed and able to sit close together. While we played, we would talk in a group call via Discord. It was precarious compared to the experience of spending time together in person, but it did produce similar levels of comfort and closeness. The social aspect of the game is one of its best attributes. Online forums swell with requests from players to swap items and ingredients. I participate in a few exchanges, and each time I feel a mixture of nerves and excitement knowing guests are coming to my island. I would play every day, sometimes prioritising in-game errands over my own, entering into a convoluted relationship with this extension of myself on the screen.

Media researcher Brendan Keogh notes that “videogame play is a complex interplay of actual and virtual worlds perceived through a dually embodied player.”[2] Whenever I interact with my New Horizons island via my in-game avatar, the game reacts, blurring my perceived boundaries of virtual and actual, embodied and outer-bodied. On a particularly draining day sometime in the summer of 2020, I watched my New Horizons character breathe peacefully in bed, and wept in mourning for a sense of tranquillity I thought I’d lost forever. Perhaps I was beginning to envy my avatar for their lack of apocalyptic anxiety over the state of the world. Perhaps this sense of envy was not a positive coping mechanism while under immense stress and in solitude. My circumstances now are different compared to March 2020, but I still find myself returning to New Horizons to seek the comfort of its routine, and to enjoy the temporality of an imagined world without fascism, disease, poverty and conflict. Over the last year, the game encouraged me to reflect on the unattainability of the type of life lived in New Horizons, and consider ways to bring elements of that tranquillity and egalitarianism into offline spaces.

Pixelated presence and absence

I can’t help but think about the future of my Animal Crossing island. Since it is a real-time simulation game, time passes on my island when I am not playing. This is one of the great things about the Nintendo series; the knowledge that your neighbours do not need your presence to go about their daily routines keeps you humble. But what would happen if I abandoned my Animal Crossing island altogether? Say my console falls victim to planned obsolescence, and I am no longer able to access the game. Or I find another way to pass the time and discard my New Horizons SD card.

I like to imagine my anthropomorphic friends would eventually start to pluck weeds and collect fossils without me. Some might even move to other islands, and invite a new cast of characters who collect fruit, change up decorations and customise furniture. Would my villagers start to miss me? Would they send me in-game letters asking if I was alright? I wouldn’t know, too busy spending time somewhere else. The lights in my lavish Animal Crossing home are off. Nobody is home. At the moment, New Horizons is an integral part of my pandemic routine. But circumstances change, as do habits. It won’t last forever.

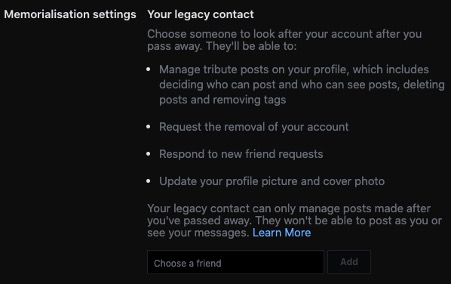

In a recent privacy panic, I searched through my Facebook settings to see if I could make my account more secure. I stumbled upon a section asking what I want to happen to my account when I die.

Facebook’s memorialisation settings

It took me by surprise. Death is a bureaucracy nightmare, and it now comes with online consequences. Who will look after my accounts, my passwords, who will have access to all the documents sitting in folders on my laptop? Who will adjust the screen brightness? Does it even matter? If I stop playing New Horizons, will my villagers assume I am dead or are they unable to make such conclusions? They don’t need me, after all. My island will continue to prosper inside the console, unaware of the lived realities around it.

I am a young and healthy person who got lucky enough to reflect on death in the abstract, and from a distance. Its looming threat seemed so far removed it was easy to disregard. This ignorance changed a few years ago when I lost a friend. And then last year, dread-scrolling through pandemic news and statistics, with the poignant words of poet Clint Smith bouncing around my head:

When people say, “we have

made it through worse before”

all I hear is the wind slapping against gravestones

of those who did not make it, those who did not

survive to see the confetti fall from the sky […]”[3]

Some users reported feeling disturbed when they discovered there is a DIY recipe in New Horizons for a gravestone – or a “Western-style stone.” Others started using it to create compelling and meaningful spaces on their virtual islands to reflect on loss and grief. There are graveyards adorned with flowers, themed rooms, a variety of spaces for remembrance, all located on otherwise lively and wholesome islands with inhabitants who never have to face death and loss.

Gravestone area from Twitter user @emiface

In times of COVID-19, players channel grief and anxiety into in-game projects to dull the pain that comes with the inability to gather with loved ones: to grieve, to celebrate, to co-exist. The more I played Animal Crossing: New Horizons, the further I realised how meaningful and transformative its impact has been on me, my friend group, and communities of fans online. We process our trauma with and through our virtual islands, our vibrant shimmering pixels imbued with so much meaning. A way to feel at ease, for a little while, before we resume to negotiate the complexity of our embodied experiences.

I am reminded of Jan Robert Leegte’s exhibition Inside/Outside from a year ago. His hyperreal landscapes were designed to continuously withstand a raging storm. I felt a techno-utopian sense of the sublime watching the work shift and roar. Multiple monitors in the space performed a beautifully crisp scene of devastation and endurance. It is unstoppable, designed to continue performing. Animal Crossing: New Horizons offers a similarly alluring and crisp artificial landscape, one you can manipulate and experience interactively, but one which also shifts and changes outside of your influence. Both pieces of media are entangled in a mess of relations between code, hardware, nature, and embodiment.

Jan Robert Leegte’s “Performing Landscape,” Upstream Gallery, 2020. [My own photograph]

Limited by restrictions and concerns, we find ourselves searching for respite in unusual spaces. It might be a little unhealthy to expect it from one source, so I do try to find meaning and connection in a variety of interactions, offline and online. But if something clicks, like the rhythm of life in New Horizons, I will not abandon ship. However, when I am inevitably interrupted by some unpredictable force, I will be comforted knowing that weeds will continue to grow on my island, even if I am not there to pick them.

References

[1] Gabby DaRienzo, Exploring Grief in Animal Crossing: New Horizons, http://www.orderofthegooddeath.com/exploring-grief-in-animal-crossing-new-horizons

[2] Brendan Keogh, A play of bodies: how we perceive video games (Cambridge: MIT Press), 2018, p. 55

[3] Clint Smith, When people say…, https://readwildness.com/19/smith-people