This is the first of what will be a three-part blog series in which we present the insightful conversation between film professor, media producer, theorist and activist Alexandra Juhasz and writer and filmmaker Peter Snowdon. Last year, the two held multiple virtual conversations at the digital roundtables of Zoom about the ubiquity of such communication methods and underlying philosophical themes such as being human in communities across distance in times of the pandemic.

In the Fall of 2020, Alex Juhasz, in lockdown at home in Brooklyn, NY wrote an email to Peter Snowdon in Belgium. They didn’t know each other, but he had quoted her once or twice in his new book, The People Are Not an Image (Verso: 2020), which she had just completed reading. They knew of each other, as people of certain intellectual/art worlds are wont to do. Over a few email back-and-forths, she explained that beyond complimenting him on his book, she hoped for something quite a bit more: might they talk? Could they record this, transcribe it, and try to share what emerged from their digital encounter about online video? These resulting words have been both edited and changed for clarity, and at one or two points extended, to give space for tracks of thought unfolding. What follows became something they named and did together online during COVID (to which they both ultimately succumbed over this time!): a demonstration of some possibilities for being alive, human, and connected, in what we hope is a non-sentimental, non-simplifying kind of way, albeit via corporate technologies and their dominant capitalist platforms.

Alex

Peter, I want to start by situating ourselves in place and time and technology—a conversation recorded and transcribed from Zoom—for reasons related to our kindred theories and practices around what you call “vernacular video.” I also need you to know that this will be my last scholarly endeavor for a while. My mother is really sick and I’m flying to Colorado this afternoon. I’m very stressed out. But I also need you to know that I prepared for this conversation as one of the last things I did in my own specific space of COVID-inspired trauma. I was just as re-energized and excited by your book this morning as I was the first time I read it, and this reminded me that our intellectual and activist commitments, and the ideas and practices that matter to us as individuals and allies, are part of what makes me feel most alive, human, and connected. So, that’s where I’m coming from: a little distracted and stressed and also a human being meeting and talking with you for the first time on a video-screen about activist digital media, what I myself called “ThirdTube” in 2007 in my born-and-stay-digital Learning from YouTube (MIT Press), so many years ago now in the short but fertile life of social media and its dominant capitalist platforms.

Figure 1: View of corporate mall/long-stay hotel complex where Alex lived, isolated for a month, in the outskirts of her hometown of Boulder CO.

Peter

Thank you for that—for making the space and time to talk at a moment that is so fraught for you, and for letting me know that for you, this conversation isn’t just another piece of work, but—like all the best things we call “work”—something that gives you energy.

It’s a strange period. As we speak, I’m sitting in an unorthodox position myself, not surrounded by books or DVDs for once, because I’m in the bedroom! My partner and I, we’re both working from home in an apartment that is large enough, but still isn’t really designed for that. But it’s quite nice in some ways to be in what is not my usual space! And I’m really grateful to you for reaching out because this is the first evidence for me that the book physically exists, aside from one friend who posted a photograph of it on Twitter just before I completely bailed out of social media in order to try and remain relatively sane. So, it’s nice to feel that the connections that can arise by publishing a book can continue in different forms in this time and even make possible some things which weren’t possible—or were at least a lot less likely—before.

Figure 2: Corner of Peter’s workspace, with detail from Anna Boghiguian’s painting of the street on Geziret El-Manial, Cairo, where Anna and Peter were neighbours in the late 1990s.

And what you said about feeling human through being engaged with reading or watching actually resonates a lot with my feelings when I was working on the whole project: which for me is indivisibly made up of the film I made back in 2013 (The Uprising), the book I have just published, and also—just as vitally—all the invisible networks of roots and tendrils around them and which connect them to each other, and which are by far, for me who was in them, the larger part of the iceberg. For there was something about the insurrections that broke out across the Arab world in 2010-2011, and about the videos produced by their actors which, when I encountered them at the time they were being made, reconnected me with a sense of my own humanity. So, if the book serves any purpose, I would hope that it is one of reconnection—in a non-sentimental, non-simplifying kind of way—that mirrors some of what I experienced when watching and working with these videos the first time.

Figure 3: Still from The Uprising (2013) / YouTube video uploaded by Gigi Ibrahim, 24 March 2011 (click image for video source).

Alex

I have gotten into the practice of reaching out to authors when I read a book that moves me. Usually just a short email of recognition and thanks. But in your case, I wanted more! I was writing voluminously in its margins as I was reading; I was so active and excited. I no longer really work on YouTube. But this isn’t because I’m not interested in its potential, or what we can learn about people, technology, activism, and video inside of and because of this corporate media behemoth. So, I didn’t just want to read you, I wanted to talk with you about people-made video, so many years after I had spent too much time in that very space. And I wanted to actively engage with you as a writer and thinker, because while our work shares an object, a political sensibility, a shared training in avant-gardist or formalist media traditions, our findings are often quite dissimilar. I’m excited to learn with you and I’m really thankful to you for your book. This is a review, a celebration, a conversation.

I thought we could start by you explaining the book and the larger project.

Figure 4: Front cover of The People Are Not an Image (Verso Books, 2020)

Peter

I think everything I do is part of my own learning process. So, I hope the book remains open-ended in its inquiry. Now that I am in some sense detached from the arguments I put forward – if only by the simple fact of the book being out there, in the world, in material form, and I cannot change it anymore – I can step back a little and look at them again.

The book grew out of making the film, The Uprising – a montage film made exclusively out of videos posted to social media in 2011-12 by the actors of the Arab revolutions. But the film too grew out of something else, because it was not originally intended to be “a film.” It became what it is through a series of decisions that were made over the years, and which were all oriented towards trying to help these videos reach as many people as possible. While I was working on the film, over two years of research and editing with my friend and partner in crime, Bruno Tracq, I was seeing lots of things that I couldn’t put in it and having lots of ideas that didn’t fit into the constraints that we had set. So, I began to write about these things in order to provide an outlet for everything that was bubbling. Over time that slowly grew into this book.

And there was also a more formal context that encouraged the choice to seek an outlet in writing: I was only able to do all that I did because I had, at a rather late age, entered a PhD program for which I had been awarded a very generous bursary. This meant I was able to give up other forms of gainful employment for a while and really just focus on my filmmaking and writing. I was doing a practice-based PhD, so as the written component, I was able to present a piece of writing that was more like a book than a traditional dissertation. I wanted above all to write something that could stand on its own, independently of the film, because I didn’t want the reception of the book to be conditioned by people’s reception of the film – I wanted it to be able to win its own audience, including among people who might not like, or might even be quite hostile, to the film itself. So, the book isn’t an attempt to explain the film, though I hope that it can provide a context which may lead some people to be able to see the film differently than they would have done without it.

In any case, the book and the film are driven by the same underlying invitation, which is that I want people to look at the videos produced by the actors of the Arab revolutions. I want people to actually take the time to see these videos and to form their own responses and reactions to them. I want to persuade people that it’s worth taking the time to engage with these images as an aesthetic proposition, not just a data point for social scientists. And I want to argue that both the videos themselves, and the act of posting them online, are worthy of our attention, whether we feel ourselves to be addressed by them directly, or less directly.

Alex

I am drawn to be in conversation with you in large part because you are doing work that I think of as in conversation or connection to mine: a practice-based engagement with contemporary political media.

You started this project by making a film, but your making was not disconnected to your writing or your PhD work. And that was not disconnected to a political project in which you seem deeply invested. Your orientation and practice as a media maker and writer invested in digital culture called to me because I don’t have many compatriots in a practice-based project itself rooted in a deeply felt and enacted political and theoretical engagement in the space of media. In my own PhD research in the eighties, I was making AIDS activist video with a VHS camcorder within my own activist community. My collective’s video activism (The Women’s AIDS Video Enterprise) became part of my doctoral research that itself evolved into my first monograph on activist media, AIDS TV: Identity, Community, and Alternative Video (Duke 1995).

Figure 5: AIDS TV and screengrab from “We Care: A Video for Care Providers of People Affected by AIDS” (The Women’s AIDS Video Enterprise, 1990)

These linked meditated iterations—making, thinking, and writing—about activist media were embedded within the first decade of the ongoing AIDS pandemic in North America. And that raises my first question: what was your political stake and position in relation to the uprisings and their videos? And did that change through the period you were making the film, and then writing your book, that is through your praxis?

Peter

Perhaps what I am most conscious of, also coming out of other films that I’ve made, whether they were explicitly political or not, is that all of them extend for me out of something that one might call not simply an ethics, but also a politics of friendship. I’ve realized over time that one reason why I’m a lousy would-be professional filmmaker is that I don’t enjoy making films with people who are not or could not potentially become my friends. There has to be a sense of complicity, and of mutual play, which can possibly – but not certainly – open up on to a deepening sense of trust. So, I guess I see friendship in this context as both a politics, and an experiment – something that may not work out, a risk that has to be taken, and which is deeply imbricated with the eventual success or failure of the film. And for me, this is far more important than anything more rationally identifiable, like a conceptual or ideological alignment, or even some participatory protocol that is meant to safeguard against the abuse of power, but will probably, or even inevitably, fail.

Alex

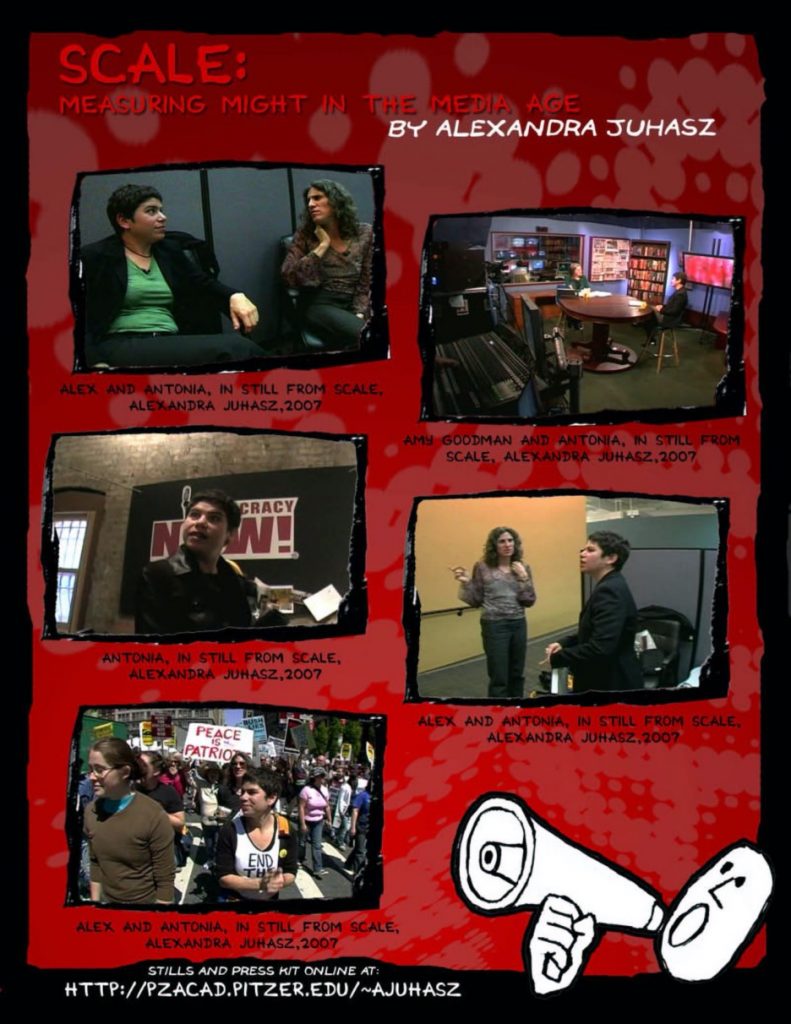

I’m curious to know what led you to believe that you could be in an ethical friendship with these human beings, these video makers. My practice as a community-based activist video maker and theorist has led me to try to make video in communities in which I already reside. So, it’s not even friendship for me, it’s shared alignment in a known community. I made AIDS activist videos when I was an AIDS activist. I made a documentary about leftist understandings of media and the scale of political movements with and about my sister, Antonia, a well-known activist and writer in the United States during and about ending the Bush administration (Scale: Measuring Media Might, 2007). I understand making media where I live, and with those with whom I want to change the world, as a feminist ethics of documentary. So, do you want to talk about how potential friendship was a facet of your politics or practice of with these videos?

Figure 6: Flier for Scale: Measuring Might in the Media Age (digital video, 58 mins, 2007)

Peter

Perhaps the basic question is, why was I watching these videos in the first place? And the simple answer is that at the time when these revolutions broke out, a lot of my closest friends were living in these countries – were from there, had been born there – and I wanted to know what was going on with them.

My work on these videos was therefore one outcome of my own personal journey over the preceding twenty years. And there were two essential stages to that. The first was when I moved from the UK to live in Paris in 1992. I was there for five years, and by the time I left, essentially 90% of my time was spent among friends who were Algerian immigrants or the children of immigrants. At a certain moment, when I was beginning to struggle with the fact of being a foreigner in Paris, through a series of chance encounters, these people had – from within their own even more complex and conflicted situation – taken me in, and adopted me, as it were. There was one family in particular who gave me a sense of being at home, even though – and, perhaps, especially because – this was with and among people who were never going to really feel straightforwardly at home themselves. This was my first real encounter with structural racism, not as something analysed in a book, or implicated in my own relative privilege (“relative” as in “situated,” not “relative” as in “less than”), but as something directly impacting the people who were at the centre of my life. But it was also more than that – it was an experience of great generosity welling up out of the centre of that injustice, despite and beyond it. From these friends, I learned something important about being a human being which connected with and deepened things I already knew, if more obscurely, through my own family background, as someone who had grown up at one generation’s remove from the working class. And if I had to sum that up in one word, it would be, hospitality.

My friends in Paris were not all Algerian, of course. When my time in Paris ran out, I’d been working for a year or so on short-term contracts with UNESCO, where I’d met people from across the whole world, including most of the Arab region. And so, as I was beginning to think about leaving a city where I felt there was no professional future for me, and I didn’t have a clue about what to do with my life, an opportunity came up through an Egyptian friend to go and work there. I jumped at that opportunity. After all, I had spent several years writing documents for UNESCO about what was wrong with the way that “the West” dealt with other peoples and their cultures, but I’d never been outside Europe. And I thought, well, what if I’m all wrong about that? I should go and see!

So, I went to Egypt and lived there for three years, working at the English edition of the Al-Ahram newspaper, and that was also a deeply transformative experience for me, both personally and politically. Not least because Cairo in general, and the paper in particular, were a meeting point for people from well beyond Egypt: from Palestine of course, but also from Sudan, Zimbabwe, Ghana… what felt like a large part of the African continent. It was also a place that looked east, towards the Indian sub-continent and the rest of Asia, in a very different way from the way that Europe did. Which meant that when I finally went to India, I arrived there from Egypt – not just in the sense that that was where I got on the plane, but conceptually, too. This helped reconfigure my inner map of the world, not just intellectually, but also physically and intuitively. It helped me realise in my bones that there isn’t just one world, one map, but many, and that “my” map – the one I had grown up with – had no particular importance or priority, in and of itself.

Figure 7: Guy Fawks, Cairo, 9 October 2012 (march to commemorate the martyrs of Maspero). Photo: Peter Snowdon

After I came back to Europe in 2000, I spent much of the next decade travelling back to Cairo at every opportunity. It was Cairo that still felt like “home,” like the place where my most important, and most vital, friendships were. I put a lot of energy into maintaining that as best I could, despite the distance. So, in 2011, when the revolutions broke out, almost the first thing I did was go online looking for my friends.

Remember, in the first days of the Egyptian uprising, there was a concerted attempt by the regime to disrupt communications with the outside world. So, I couldn’t get in touch with anyone by email, and the telephone lines weren’t working. But many of my friends were journalists, as I had been when I lived in Cairo. I knew that if anyone had access to a satellite phone, it would be them. I might be able to find them online to see if they were safe, even if I couldn’t talk to them directly. Almost immediately, I fell down the rabbit hole that is social media in times of popular unrest. And at the bottom of the rabbit hole were not just many of my friends, who were, by and large, doing okay, but also all these people making videos. And suddenly, I was spending all my waking hours hanging out with these videos, and with the people who were making them, some of whom I knew personally, and some of whom I came to know, or at least be in contact with, through the online connections forming around these events.

A lot of this activity was sharing videos and talking about them, and that combination of circulation and discussion stuck with me. Everything I’ve done since is basically an attempt to enlarge (or recreate) the circle of that initial sense of residing in a community through video – a community of discourse and exchange that goes well beyond just looking at images, and includes many, many layers of displacement and non-coincidence.

Alex

Your words resonate with what draws me to social media as well. I became a theorist of the internet and internet video in the decades after my AIDS work because my media praxis has always been medium agnostic. I am not a theorist or maker of video or film or websites per se. Rather, I’m an activist and a human being who wants to be in community and change the world with like-minded people using whatever medium is at hand. Your “being human” in community across distance is particularly resonant to me, especially because I’ve been recently working on practices of media proximity, given the protocols of social distancing and the fact of fake news (fakenews-poetry.org).

Figure 8: Participants at the New Haven Fake News Poetry Workshop, one of 25+ held around the world from 2017-ongoing.

My current work on fake news and radical digital media literacy (including a 2021 book co-written with Nishant Shah, Really Fake! that blends out creative renderings of situated authentification through stories, poetry, photos, and dating, in its many senses, temporal and inter-personal) strives to be human together while not letting go of technology. Media suit or align with their people, struggles, and places. I appreciate how your work on vernacular video is situated in a specific local and temporal struggle—what became known as the Arab Spring—itself locally and differently experienced across the countries of the region, and the changing conditions of their struggles. You name here and with more detail in the book, how making video and then also talking about and sharing this is a powerful place for political empowerment, agency, and humanity making—well, I agree with you—and am pleased to learn about this in both its situated and distributed formats.

Peter

For me, too, these videos were never just about “video”. They were always about experimenting with the multi-layered nature of community via technologies that preserve or repurpose some of those layers in order to bring us together differently, even as they create new kinds and qualities of distance and absence. And that is also what we are doing “here” today – coming together differently to trace out yet another path, or at least one segment of what may become one, through these fields of presence and absence we call “media”.

––

Read the second part to the conversation here.