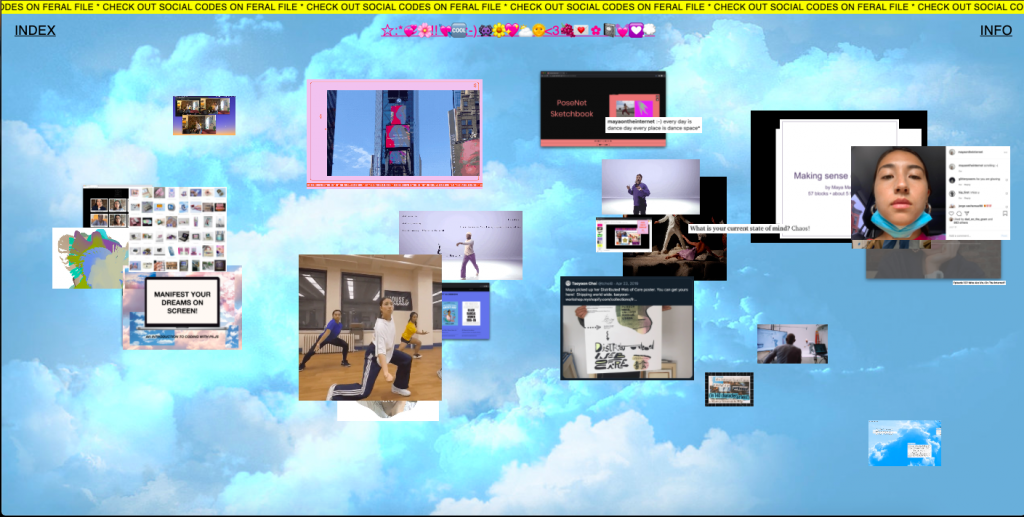

Maya Man is a young artist, dancer and technologist from New York. Utilising her background in coding and computer science, she makes projects that enhance and expand online experiences. Her work incorporates themes of joy, nostalgia and curiosity all at once, often leaning on early internet aesthetics while projecting a vision of embodied technological bodies into the future.

Maya’s art excites me because it celebrates the possibilities that open up when people and machines work together, and avoids falling into naiveté over the possible risks of such collaboration. I hope more people recognise the potential her works have to change our relationship to the internet and AI. My aim here is to show and discuss a few key works, and invite you to explore Man’s projects yourself, as they are best when experienced first-hand.

Moving with the Machine

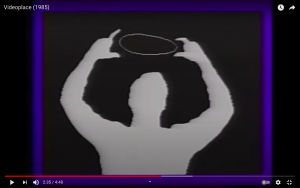

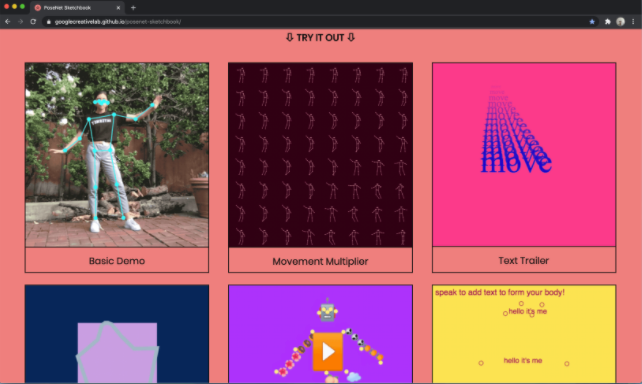

PoseNet Sketchbook was the first Maya Man artwork I saw online. It is made with a modified algorithm sourced on tensorflow.js. PoseNet is an open-source library of code that tracks a moving body and creates a variety of distorted moving images based on the user’s movements. When I saw the work, I immediately thought of Myron Krueger – “a pioneer of interactive media art”[1] – and his innovative work on immersive environments in the 70s and 80s.

Both works show an interest in tracking and modifying the movements of a body. However, I thought Maya’s work facilitated a more intimate relationship between the participant and the technology capturing their movements. Since the 1970s, our understanding of developing everyday technologies deepened, and various machines entered our daily lives and the very fabric of societies. This shift irreversibly affected how we interact with everyday technologies, and influences the level on which we acknowledge or bypass their existence and visibility.

In Kruger’s immersive environments, the experiences were communal, new and exciting, all-encompassing for as long as participants interacted with the meticulously-built environment. Man’s work, on the other hand, disenchants the spectacle of technological possibility and represents the inseparability of our entanglements with the machine. PoseNet Sketchbook exists in multiple places at once, on computer screens of individual users as their shapes shift, distort and layer. The miracle of endless possibility is gone. Now, we explore what to do with what remains. Each movement is like a brushstroke, and the effect lasts for as long as the browser tab is open. There is something beautiful and pure in this temporary interaction.

An intimate staring contest

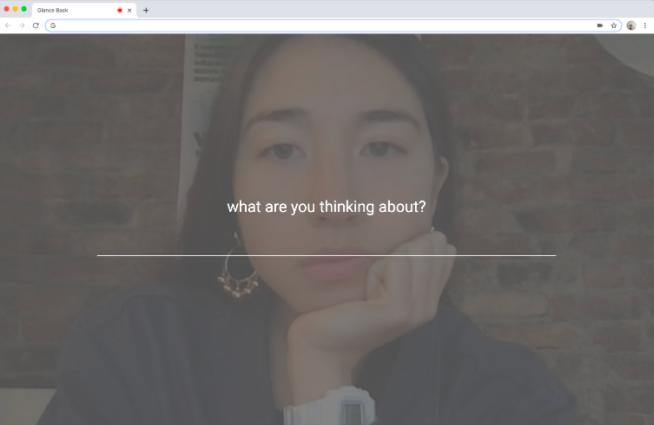

The idea of close encounters with daily technologies appears in Maya’s other works, establishing itself as a theme. The screens of users are their primary mode of exhibition and existence. Take, for instance, Glance Back, a Google Chrome extension that captures the webcam image from a device once a day and prompts the user to record what they were thinking about at that moment.

This process makes visible the data collection that already occurs in search engines and on other platforms that facilitate our online activity. While the browser extension asking you about your thoughts might be jarring to some, it is simply a more streamlined and direct cousin of algorithms that track and predict our actions. Glance Back adds nuance to these relations. It acts as a personal diary and prompts personal interest in the performing machine. Unlike other modes of online surveillance, Glance Back operates under the agency and consent of the user. Maya explains: “It’s important to note that all of the photos are saved to your browser’s local storage. This means that they never leave your machine. This is a collection shared purely between you and your computer.”[2]

I think Glance Back acknowledges the physical and emotional closeness between ourselves and our machines, especially now, when we use them to work, relax, but also socialise with other internet users (including our loved ones). Or, more specifically, “Glance Back” allows users to decide whether or not they wish to share such personal data with the extension. Choosing to download it can be an act of making visible the personal connections many of us already have with our devices. However, can it lead to acknowledging this relationship might be toxic? I am not sure. I would love to see Maya engage with the concept of surveillance capitalism and the attention economy further in her practice, especially as she continues to collaborate with the Google Creative Lab.

What are you willing to share?

What happens when we willingly share personal information online? A few things. We begin building an archive of feelings and reflections; a sporadic, erratic digitised diary. We hope somebody out there listens, interacts, relates. We might even share things online that we are unwilling to communicate face-to-face. However, doing this invites unwanted attention too, and provides a source that others can use in malicious ways in the future.

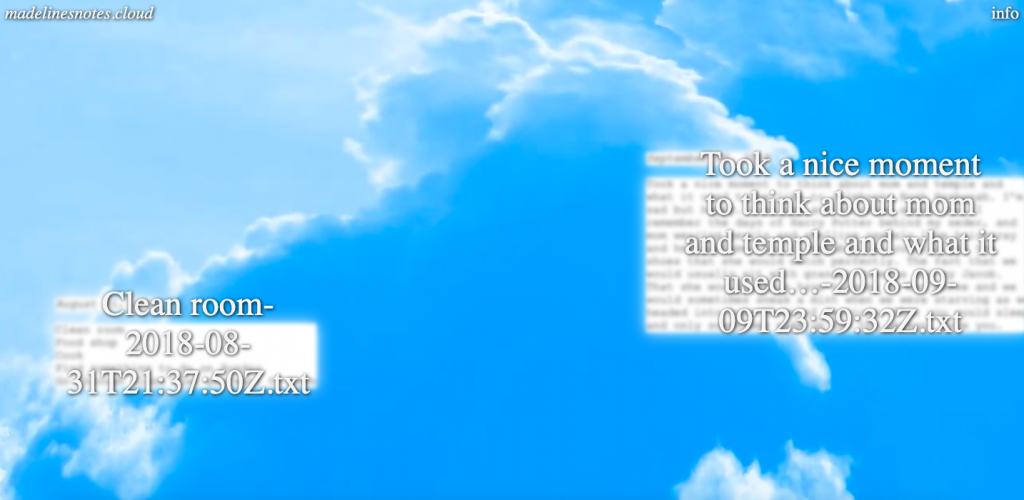

Using code as her medium, Maya reinterprets Madeleine’s large file of personal data she’d shared with the artist. Maya built a website that shows notes from Madeleine’s iPhone. What emerges is an intimate portrait of a young woman recording significant, useful and introspective information over the years. For personal use, until now. Looking at the website, I feel like an intruder, even though I am aware she shared the data willingly. Still, it feels too personal to be accessed by just anybody.

I cannot help but keep swiping and reading note after note, and the blue skies in the background add to the whimsical, otherworldly feeling the website evokes. Can this be a modern-day confessional, embedded in code and designed to fit a specific aesthetic, a millennial nostalgic about websites they grew up visiting? I am conflicted, but I keep looking. I realise that this project shows online activity does not have to be so heavily curated. Madeleines.notes and Glance Back take away the users’ ability to select, edit and filter content that reflects who they are. Why not give that agency away? To think how many hours I’ve spent thinking about how to present myself online. I am sick of it now, like many others. I want to refuse to participate in the spectacle, but I am unsure how. Is there an alternative way of relating to social networks? I see Maya’s work can be a stepping stone towards a more balanced and healthy relationship between our actual selves and our virtual/online extensions.

Digital Literacy Now

Maya’s presence online takes many forms, but always carries an interest in embodying compassion and care through machine learning and code. I consider her website to be an artwork in and of itself, a source for artworks and education; points of departure. The Racial Justice Bookshelf needs to be mentioned here. It is a resource made to make it easier to buy anti-racist books from black-owned businesses in the US. Then there is are.na; Maya’s scrapbook of inspiration and information, an ever-growing archive of online happenings and references.

The difficult part is this: Maya’s work does require quite a high level of digital/internet literacy. In the beginning, I struggled to understand how are.na or GitHub work. However, when I moved past confusion, I started to appreciate and see the exciting potential of alternative platforms, creative coding, and the artistic expression they allow.

Maya speaks openly about her passion for computers and coding, and her interest in facilitating new interactions between bodies and everyday technologies they already encounter and absorb. The future of online content can be more transparent and genuine, based less on the logic of the attention economy and more on the needs and interests of individual users, who come together to experience and share their embodied technological selves. It starts with looking back at the machine that is already watching.

References

[1] Mark Hansen, Bodies in Code: Interfaces with Digital Media (New York: Routledge), 2006, p. 25

[2] Maya Man, Glance Back Info page [Accessed April 2021]