“A journey implies a destination, so many miles to be consumed, while a walk is its own measure, complete at every point along the way.” – Francis Alÿs

Most of us are used to knowing that our devices track how we interact with them and monitor what we do when they are around. But the Health app, built-in on iPhones, has been causing me a lot of grief lately. What started as an innocent interest in the number of steps I take has grown into an issue. Is tracking steps a helpful tool for becoming more active? Or is it more damaging than helpful in this context, that is, is it easier to associate the level of physical activity with productivity and, by extension, self-worth? I propose to explore the differences between pre-pandemic walks and what I’ve been calling corona walks/COVID walks.

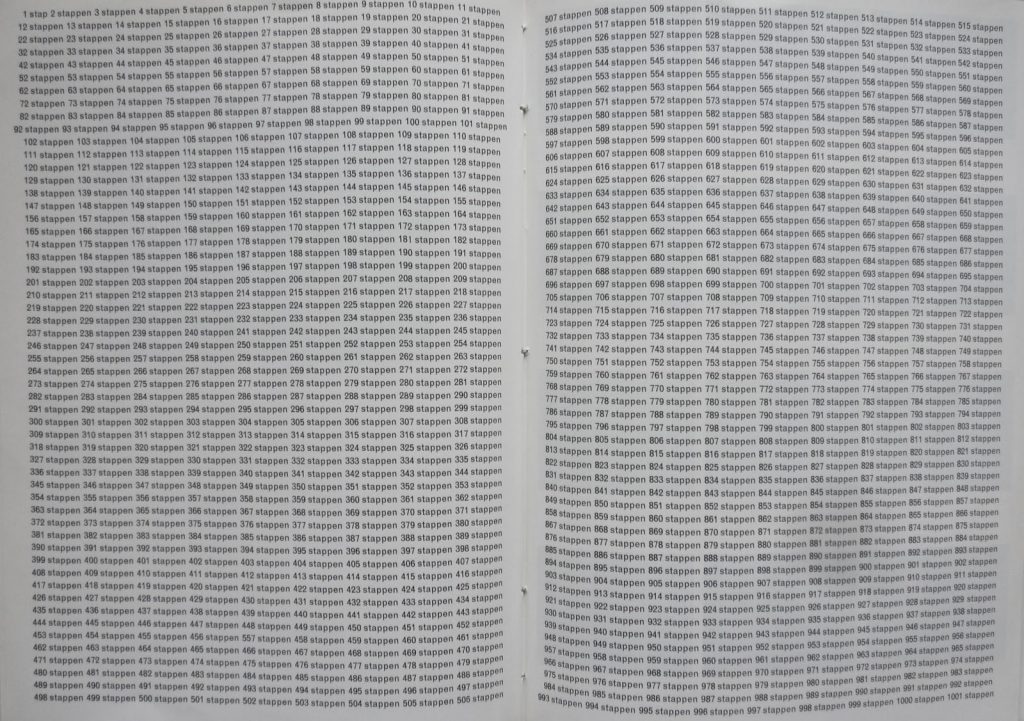

A weekly report on the Health app.

Before the pandemic, I knew that my phone had an app installed that tracked my steps. I would look at it occasionally out of curiosity but did not feel compelled to check it often. Then, the pandemic began, and suddenly almost all options for spending time outside seemed dangerous. My relationship with walking started to shift. Going on walks became a promise for a better mood and a better day. The alternative was dire, sitting in a studio apartment, breathing stagnant air, unmoving and worrying about the future. I would walk to take my mind off things and to have at least some variety in an otherwise homogenous routine.

Soon, I found myself performing for my phone. I would check it during walks to see what mark I was hitting. Am I over 5,000 steps, or still around 3,000? When the weather was bad, I would sometimes pace back and forth at home, phone in hand, watching as it registered each step. As an avid social media user, I had found another way to gain instant gratification. I watched the numbers go up and felt better about myself. Until I felt like I’ve performed enough. Then I would leave the app alone, until the next day. Rinse and repeat. But it doesn’t have to be this way.

Artist Stanley Brouwn’s manual step-tracker app. “A Distance of 336 Steps” (1971).

My granddad, a now-retired but still academically active professor, loves to walk. Like many, he believes that walking clears his head and helps him come up with good ideas. I grew up believing that going on walks can solve a lot of things. Above all, it offers a new perspective, getting rid of stagnant energy and providing needed stimuli.

I appreciate the physical and psychological benefits of walking. But being an able-bodied person without a driver’s license or a car means that walking is also my most reliable form of transportation, especially when using public transport is not advised (but, of course, sometimes necessary). So, I find it hard to separate a utility walk from a leisurely walk. I walk fast because I am used to walking to get somewhere, do something. Living in the Netherlands changed this a bit, as now I rely on my bike to run errands. But the habit of walking “with purpose” persists. Even now, over a year into my corona walks, it seems I cannot slow down.

Asking around

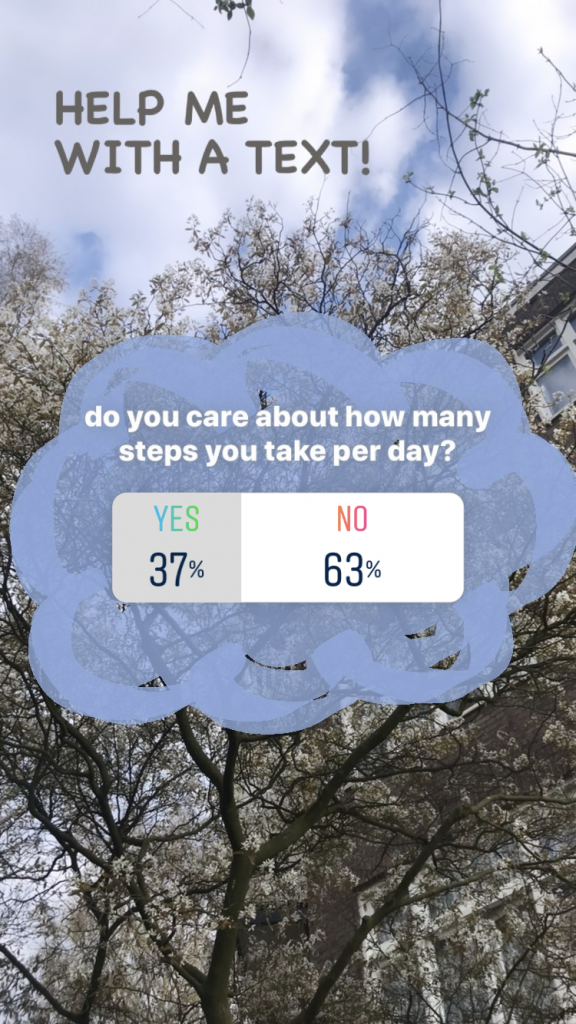

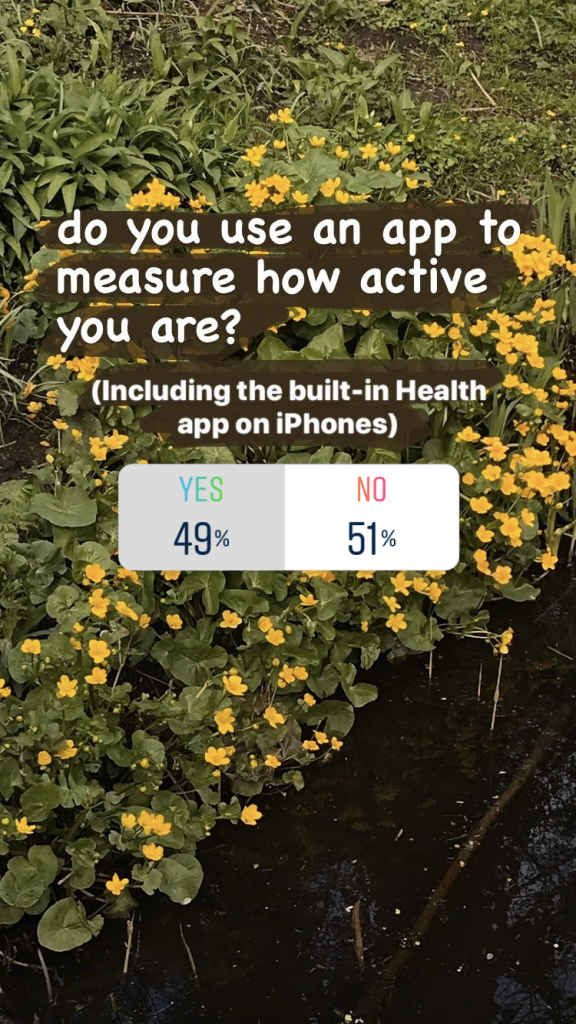

I asked on my Instagram story if my friends and acquaintances cared how many steps they were taking and if they used an app to measure their physical activity. Forty people responded, most of them reporting that step counts did not matter that much. But the split was almost even between those who used health apps and those who did not. (See below.) This suggests that some people have health apps, either built-in or downloaded willingly, but they do not check up on them daily, or tracked activities other than walking.

.

.

I wanted to know more about other people’s experiences over the last year, so I asked a few close friends about their changing relationship to walking. James said that before the pandemic, he did not go on leisure walks as his job required him to stay on his feet all day. But nowadays, he says, “I always feel better after a walk, even if there were too many people or my feet hurt.” He elaborates: “I had my first proper cry on a walk in about three years. I’ve never felt claustrophobic in my flat but there’s something about how big the outside is that it just felt right, to fill the space.” I love this perspective. It makes me think that going on walks nowadays is a more embodied way to experience something outside of ourselves, something more tangible and fulfilling than observing an endless stream of information online.

According to John Wylie, landscapes represent the “creative tension of self and world.”[1] So, experiencing a changing landscape can be a way to reconcile something within ourselves, exploring these tensions. Corona walks are also about control. Living through a pandemic is an extreme exercise in letting go, accepting there are some events and consequences we cannot influence or neutralise. So, we go outside to be somewhat in charge of our surroundings. The views change as we walk, serving as a reminder that time continues to pass outside of our homes, outside of ourselves. Still, a level of unpredictability prevails, even on a calm walk.

Walking around Leiden last summer.

Frédéric Gros is a philosopher of walking. In an old Guardian interview, he said: “You can be replaced at your work, but not on your walk. Living, in the deepest sense, is something that no one else can do for us.”[2] Do we walk to prove to ourselves we are alive, living, and moving through time? It makes sense to me. Walking grounds me, connects me with my body, and helps me relate to other walking, thinking bodies who walked before me.

Walking is also a manifestation of slowness. It is a refusal to optimise, streamline, be efficient and generate profit. Walking requires your attention, and (usually) gets you away from your working self. It asks you to slow down and take stock. This is why I see it as a challenge. My habits speed up my walking pace as my mind starts to wander towards work plans, ideas, anxieties. This inability to take a break is a product of late-stage capitalism. Even when I try to think about something else, it creeps back in, beckoning me to do more, quicker, better, promising I will feel more useful if I increase my productivity. But I do not want to give in. So why am I still compelled to know how far I’ve walked?

Today’s everyday technology allows us to measure everything, monitor performance. Media outlets advise us how to be on our A-game, and how to cut out whatever is unnecessary. But who gets to decide what is and isn’t urgent, needed? Why should I feel compelled to shove my phone under my pillow each night to let it track the quality of my sleep? To go on walks with my phone in hand, feeding it a stream of information about my whereabouts? I do not see how I can benefit from these forms of self-surveillance. Sometimes I wish we could go back to a time when phones allowed for communication and not much else. But we cannot go back. We have to face the privacy threats that come with our wearable personal technologies.

There must be a middle ground. Perhaps it is time I disable “Fitness Tracking” on my phone altogether and move however and whenever I want. I do not want to perform for my phone anymore. I want to peel away from it and enjoy time apart.

Looking inwards

Independent, aimless walking allows us to step into ourselves and think about how we relate to the wider world; the actual world, out there, continuing to change even if we are not walking through it and witnessing it. Gros talks about how walking helps to go into autopilot mode, during which we synchronise with our bodies and glide for hours at a time (if your health allows it). This perspective makes walking sound like a primordial, almost ritualistic activity. Why not? Magic has been syphoned out of Western everyday life. Walking can be a vessel for restoring some of that meaning into our routines A refusal to hurry and perform labour makes space for meaningful connections with ourselves and our surroundings.

In the Nintendo Switch game “Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild,” you have the choice of travelling around Hyrule on foot or a horse. Sure, the horse can take me around faster, but I quickly find myself missing the slower pace of walking in-game, and how much easier it is to notice the details I would have otherwise missed.

Exploring the landscapes in “Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild” on Nintendo Switch.

When I talked to my friend Max about corona walking, he said: “I kind of like having my phone tracking steps, but maybe that just comes from growing up playing video games. I like to know the stats from time to time.” I get that, and it is hard to remove ourselves from measuring our performance. Maybe I am making it sound all too serious. If walking can be a ritual, I don’t see why it can’t also be a game. If we treat our data with some distance, we refuse to be controlled by it. Gamifying everyday tasks can be another way to restore some of the joy and spontaneity we’d lost through excessive planning and obsessive control over our performance.

Maybe we are in a contemporary digital panopticon, willingly giving ourselves over to constant surveillance in exchange for surface-level interactions? Foucault says that a participant in a panopticon structure “is seen, but he does not see; he is an object of information, never a subject in communication.”[3] Our phones were meant to be communication devices, but they act more like data extraction devices. We are given a degree of seeing and engaging, but the price we pay is high – boredom, dissatisfaction, inaction, radicalisation.

I am unsure how to find a way out of this mess. In fact, I might have internalised the panopticon, watching myself from the watchtower as I sit in the cell, pacing and watching the numbers go up. But it can change. I can refuse to participate in the spectacle of constantly measuring myself and my self-worth based on faulty interpretations of productivity. I am growing less interested in my performance, my stats. Doesn’t that take away some of its power?

I have been in locked-down Amsterdam longer than pre-corona Amsterdam. It is sad, but it’s also something I cannot change. So, I go on walks. I see new sights as I glide around town, growing more familiar with these spaces. Sometimes, I catch myself worrying about my stats. Other times, I allow myself to just be, and for that to be enough. Change isn’t linear, but by consistently questioning and readjusting our positioning to digital power structures, we might begin to take back some of the power that self-surveillance holds.

References

[1] John Wylie, “Landscape and Phenomenology” in Routledge Guide to Landscapes; p. 62

[2] The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/apr/20/frederic-gros-walk-nietzsche-kant [Accessed 28 April]

[3] Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish, p. 200