“We need to focus on what remains unrendered, or unseen – what we are blind to.” – Rosa Menkman

On Friday evening May 14, 2021, the National College of Art and Design in Dublin and The Digital Hub hosted a webinar with Rosa Menkman and Joanna Zylinska. It was the fifth event in the Digital Cultures series, and my first time tuning in. I expected a straightforward panel discussion, but after the host, Rachel O’Dwyer introduced the two artists, we were shown two presentations first by Rosa and Joanna. Seeing them back-to-back provided a nice opportunity to notice similarities between their areas of expertise and differences in how they approach machine vision and algorithmic blindspots.

Rosa’s presentation “Destitute Vision” demonstrated her keenness to experiment with alternative forms of lecturing. In a mesmerising 15-minute work, she explores how artistic interventions can help us understand technologies of perception. In a calm voice-over, she proposes that data has the potential to be fluid, but it is the architecture through which it moves that distorts it and molds it into a singular form. Instead of asking what algorithms see, Rosa inquires what they render invisible.

Rosa Menkman glitchy “Vernacular of File Formats” (2009-2010)

I enjoyed learning about her “BLOB of Im/Possible Images” project, a playfully named 3D gallery that shows images chosen by a group of particle physicists, who visualised important concepts or phenomena that cannot (yet) be rendered. I can see how this type of speculative thinking opens up new possibilities for understanding each other across disciplines and types of expertise.

Still from Rosa Menkman’s “BLOD of Im/Possible Images,” found on newart.city (click on image to visit).

Joanna’s presentation explored her experience of using an Artbreeder GAN algorithm to render images of eyes and brains, which turned into an artwork titled “Neuromatic.” Her choice to focus on these body parts points to an interest in pinning down what exactly constitutes seeing. She explained that even though we know a lot about the human body and its complex processes, the phenomenon of seeing remains somewhat of a mystery.

In her research, Joanna considers what it means for humans to endow machines with the capacity of seeing, and inquires whether machines can see at all. Her approach proves the value of artists borrowing from other fields – in this case, from philosophy – to tackle a concept they deem interesting. Indeed, later in the discussion, Joanna talked about how her practice requires re-learning biology and philosophy and using their knowledges in a way that breaks rules and poses unconventional questions. These methods are usually inaccessible by scientists, who are more limited by funding requirements and goal-oriented methodologies.

What followed the presentations was a productive discussion about collaboration, modes of seeing, and the role visual arts play in rendering visible different technological and biological phenomena. I left the event feeling like I got to look at artistic research from a new angle, one that reveals their playfulness and lack of rigid expectations as assets and activators of interdisciplinary understanding.

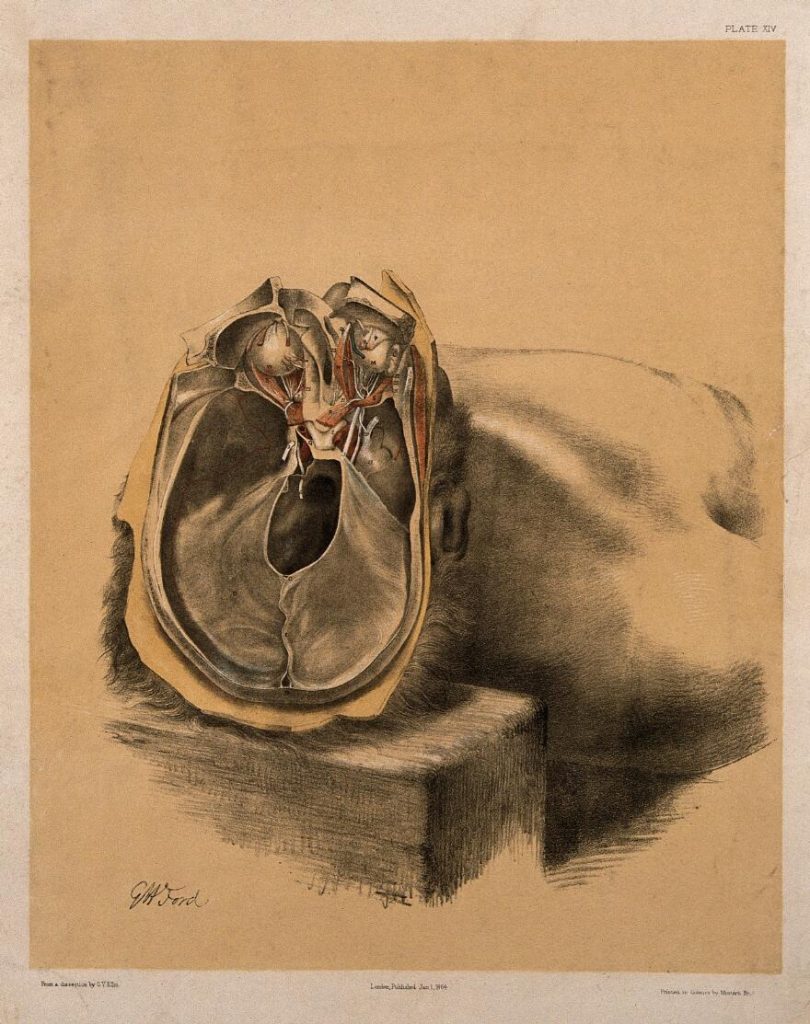

Found on the Wellcome Collection, which Joanna used to source original images for “Neuromatic” video: A dissection of the skull, showing the eyes with attached nerves and muscles. Lithograph by G.H. Ford, 1864.

In the discussion, Rosa pointed out that scientists want to open up their knowledges to other experts and communities, and that artists are often a bridge between scientific fields and people who are unfamiliar with them. Similarly, Joanna noted that artists often deal with the same themes as engineers or scientists, but the endpoint of their projects tends to differ, and their scope can be broader.

On the topic of interdisciplinarity, Joanna pointed out that jumping between fields reveals similarities between them, but also shows their respective blindspots. She stressed that the aim shouldn’t be to create some sort of (unattainable) universal knowledge, but rather to notice each other’s limitations and find common ground, without flattening the differences that remain.

What started as a conversation about specific themes – machine vision, algorithmic limitations, collaboration – shifted to a meditation on why people desire to model and represent the world. Joanna asked if there is a single world out there to be represented, hinting at the intrinsic subjectivity of perception and sensations.

“Vision is just one of the senses, it is never just vision because it’s always already expanded, it’s environmental, it’s always been haptic. But the human has been constructed as a visual being. There is a history of vision and the human as a visual, visualising subject. We have to address that history.” – Joanna Zylinska

The discussion also carried climate urgency undertones, as the guests noted the importance of recognising non-human actants in the world in our explorations of modes of perception. Instead of seeking a “total vision” that encompasses different kinds of experiences, Joanna suggested that treating this concept as a speculative, artistic question allows for exploring the human desire to understand our limitations.

Joanna noted she could see a corporation exploiting an idea of “hyper vision.” Yes, I can imagine a neoliberal Tesla-esque project using computer vision to obtain the “perfect” way to see and analyse the world. Elon Musk would announce it at a self-serving event, claiming he is changing the world, only to grant access to this new “product” to a select few, dodging critique and refusing to consider why a “total vision” would be a good idea in the first place. In this ecocentric and capitalist mode of thinking, to see the world from every angle would mean to own it from every angle.

In the end, it boils down to agency. Knowing that current infrastructures of digital cultures are shaped by profit- and data-oriented corporations, we have to be vigilant when thinking about who acts as a user and who is being used. Both Joanna and Rosa discussed these power structures. They highlighted that algorithms – sometimes perceived as abstract and incorporeal – have very real socio-political consequences, often harming already marginalised groups when used in the hands of immigration enforcement or banks.

Trees have eyes in Rachel MacLean’s “Eyes to Me” video.

For me, the all-encompassing influence algorithms already have was the most important takeaway from this event. Artistic interventions can shed light on the shadowy inner workings of certain algorithms without vilifying them. We have to acknowledge the limitations of our perception – literal and conceptual – to engage with other modes of seeing.

Learn more:

Watch the full event back on YouTube.

See other events in the Digital Cultures series here.

Read Rosa’s recent publication, Beyond Resolution.

Read Joanna’s recent publication, AI Art.