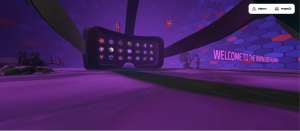

I click on a weblink that prompts me to join a room. The room is dark and drenched in a purple hue: blue and red hexagonal tiles rotate along the perimeter. Large text reads “WELCOME TO THE WWWUNDERKAMMER.” Up ahead is a massive VR headset with portals in the place of apps revealing a map that allows me to transport to other rooms. There are 22 from which to choose. I click on one and enter. From there, the tour begins.

Time feels slippery as you explore New York City-based transmedia artist Carla Gannis’s wwwunderkammer (2020), an immersive virtual installation. At once anachronistic and futuristic, you’re both taken back in time and catapulted into the future. This is how one might describe the internet, a database, or any other collection of information, which is what the wwwunderkammer is at its core: an archive. Inspired by the 16th century wunderkammer (German for “wonder chamber”) of Western Europe, the wwwunderkammer is a cabinet of curiosities updated for the 21st century, as denoted by the work’s name, a cheeky reference to the world wide web. The original wunderkammer were a kind of proto museum that housed a curated selection of objects. “They were entire rooms,” reflects Gannis, “often filled with exotica, and then we run into the problematic sub-orientalism, exoticism, and of course colonialism.” References to art history, popular culture, and politics are a fixture of Gannis’s work, but she is careful to avoid reconstructing historical references and, instead, contextualizes them pluralistically, a “remixing” of history that speaks to her interests, which are, in her words, “vast, and large, and maximalist.” In contrast to its predecessor, Gannis’s wwwunderkammer reflects this sensibility toward openness and maximalism. She and I spoke at length, avatar-to-avatar, while teleporting around the wwwunderkammer together to discuss how it came together and how she plans to expand it.

As an interactive digital installation, the wwwunderkammer’s behavior is, by design, performative and unstable, resisting a centuries-old didacticism and power dynamic common to curation and collection practices. Rather than entering a fixed space of collected information, one gets the impression of entering a place that is meant to be meaningful but shifting. Like many of Gannis’s projects, wwwunderkammer is iterative, entirely or in part translated into evolving formats to accommodate different venues, platforms, and accessibility requirements, and thus yields different participant experiences. The work began in a brick-and-mortar setting with a debut at Telematic Media Arts gallery in San Francisco, USA in the fall of 2020. Comprising physical objects, prints, video animation, and XR (virtual reality and augmented reality), the exhibition was cut short by the Covid-19 pandemic shutdown. Like most things, the wwwunderkammer then went online: Gannis completely adapted the work to a virtual installation using Hubs by Mozilla, an open-source, customizable mixed reality VR chatroom accessible through headset or web browser. Being forced to move online was, in a sense, a useful fate for this project, as it then had the opportunity to not only engage but inhabit and enact the language of the internet more fully.

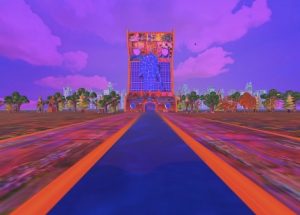

A screenshot of the runway leading to the game cabinet castle.

“It is an object of the internet with its own digital materiality,” says Gannis, who consulted her architect partner while creating the preliminary sketches of the chambers and access points of the virtual installation. Visitors can enter through multiple pathways. There is a lobby and a main gallery, both of which are organized to guide visitors toward different collections, plus a game cabinet castle entrance that leads you down a long runway toward a giant retro video game arcade cabinet. The environment references some of Gannis’s inspirations: the wallpaper inside the main gallery is a nod to Janet Murray’s pioneering Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace (first published in 1997), the grid pattern on the “floor” is a reference to the science fiction horror film The Lawnmower Man (1992, dir. Brett Leonard); and “a cabinet of curiosities without a video game cabinet castle in the 21st century would be remiss,” quips Gannis.

There are references to popular culture, tech history, and science fiction everywhere. Gannis mentions Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s surreal TV series World on a Wire (1973) in passing, demonstrating her orientation toward speculative fiction. Digital objects line the walls of the main gallery and are perpetually animated, a stimulation of jittery GIFs. The names of content experts flash and link to pre-recorded interviews as hidden Easter eggs among the maximalist wall-to-wall collection. The vibrant aesthetic of the environment is owed to the use of high-key, saturated colors of mostly blue and red, which together form a bold purple. This color palette is a way to “subvert the formal or traditional architecture that we’re in right now.” One could say it’s also a way of pulling us inside our screens and into our long-term memories, accessing the fictional worlds of science fiction film and literature. The speculative fictional worlds of our collective imaginations are here reenacted.

The main gallery of the wwwunderkammer.

The sensation of mutability this produces is intentional. Having worked in a library — Gannis’s first job in New York was running the library at the New York Studio School — she acknowledges the limitations of archives as biased storage sites and narrow communicators of cultural knowledge and invites us to reconsider their static and didactic positions. “In terms of the experience itself, I like it being open to interpretation. You don’t see wall tags, things that are delineating what these different cabinets are, because I think of this as a visual language with a kind of surrealistic bent that is open to interpretation and has more fluidity in that way,” explains Gannis. In formally remaking the archive, she is in a sense rescuing the archive from itself by bringing it to life rather than allowing its contents to get lost in obscurity.

The wwwunderkammer does more than house information about history, politics, art, and cultural values. The work itself is performative. In this way, the wwwunderkammer performs the archive, not merely exists as one. This distinction is important. As we wander around the wwunderkammer together, Gannis clarifies how she thinks of each of the collections, which have their own locations, as places rather than spaces. “Spaces are more functional and serve a utilitarian function,” Gannis muses. “I feel that these are more places: they have a specific intent and cultural resonance.” Objects dance and jiggle in place, music pulsates, hyperlinks flash: all as if electrified by the material contents of the built environment’s infrastructure. The wwwunderkammer radiates an energy unique to the internet: an everchanging, dynamic place of cultural knowledge, both represented by the archivist and the archived. This is also advanced by the collaboration between Gannis and other artists and thinkers who’ve curated their own wonder chambers and given expert interviews with one of Gannis’s alter ego avatars. This phase of the project is about expanding the cabinets Gannis initially conceived based on the scholarship and expertise of others through interviews conducted by Gannis’s AI-controlled avatars, which are accessible from the main gallery. Charlotte Kent reflects on humor and the absurd; Leah Roh addresses the importance of sex positivity, and Regina Harsanyi discusses digital preservation. Gannis has plans to include additional chambers and interviews to increase the depth and breadth of cultural information offered through this evolving project.

A screenshot of Leah Roh being interviewed by Moira.

The wwwunderkammer is doubtlessly the product of a cyberfeminist ethos, which is a feminist approach to the use of and creation with technology that imagines and fosters alternative practices and politics toward operating differently in the world. One of Gannis’s cabinets features Lucille Trackball — an AI-based stand-up comedian Gannis created about three years ago — and is “dedicated to female-identified comedians from around the world, of different abilities and of different gender orientations.” Among other things, it’s a response to both the reinforcing of gender bias through female-sounding voice assistants in computing and the use of humor as a way for women to obtain agency. Lucille Trackball comedically interviews Charlotte Kent to talk more about the latter. AI, in this context, isn’t promoting a new commodity, rather a new interface and intelligence centered on humor. Likewise, AI is used to train the wallpaper lining of the shelves of the cabinets with image datasets Gannis created. Hardly noticeable without having it pointed out, it “speaks to the fact that almost all of our experiences today involve some aspect or mechanism of AI.”

The dark side of AI and computing sit in contrast to the high-key colors as crucial reminders of the reality and complexity of our digital environment and the world in which it is created. Though Gannis dispenses with labels and taxonomies that might restrict meaning, there are signs everywhere of her sociopolitical awareness. The word DECOLONIZE and a reference to Ruha Benjamin’s concept of the New Jim Code — discriminatory designs that encode inequity — flash alongside text that reads BLACK LIVES MATTER and an emoji wearing a protective face mask, among other signifiers of the past year and a half. In other cabinets, the word VOTE, an Etch-a-Sketch, a hashtag, a copy of Frankenstein, endangered animals, and other objects collectively and fragmentedly tell the story of life, death, humanity, society, politics, technology, and more.

As an archive, the wwwunderkammer performs the admission of its own limitations: it relies on the contributions of others, responds well to flexibility, and rejects the goal and claim of completion. These are markers of a unique kind of technical object that pushes against the established order in the age of the database, the primary mode of cultural expression and post-narrative device of the 21st century, to borrow from Lev Manovich. But Gannis’s work is additionally subversive in its attempt to decolonize the archive through its reimagining, shared authorship, and inclusivity. “We are faced with the reality,” writes Legacy Russell, “that we will never be given the keys to a utopia architected by hegemony.” As a work that performs the archive, the wwwunderkammer is designed to mutate and respond to various needs and prompts, being created in necessary fits and starts, which are sometimes presented in the form of a glitch or problem. Moving the work online is one important way to make it available virtually everywhere and for everyone, but even this has its limitations. Gannis recalls that an earlier iteration of the main gallery was created in a higher resolution, which prevented some visitors in Western Europe to easily access it, based on their connection. Gannis had to reduce the quality of the work, lowering the barrier to entry, to again conform to the language of the internet.

Here it’s easy to recognize hints of Hito Steyerl’s poor image. In her essay, In Defense of the Poor Image, she discusses the hierarchy of images and the neoliberal impulse to insist on the “aesthetic premise” of a “rich image” at the expense of sharing it. The tragedy of this snobbish inclination is that images are often rendered invisible, “disappearing again into the darkness of the archive.” Poor images, by contrast, are “popular images—images that can be made and seen by the many.” For Gannis, sacrificing quality benefits the masses, democratizing the image and thus rendering the archive an accessible place. Likewise, it doubles as a force against the possibility of feeling pedantic. “In a way, being less crisp, it gives more room for the intention of these kinds of constructions, these taxonomies not being static, not being fixed or completely clear.”

The wwwunderkammer behaves more like an archive for the people, a library open to all, than a proto museum, like its predecessor. The work, like every performance, will change and adapt, reflecting the material instability of the digital object as much as the culture, politics, and people it represents.

—

NATASHA CHUK is a critical theorist and writer whose research and interests focus on creative technologies as systems of language at the intersection of formality, expression, interface, and perception. She teaches courses in film studies, video game studies, digital cultures, aesthetics, and art history at the School of Visual Arts in New York City.