In this blog series, INC research fellows Natalie Dixon and Klasien van de Zandschulp explore a burgeoning intimate surveillance culture in neighbourhoods across the world. At the core of this research is a flourishing network of surveillance technologies produced by Silicon Valley and perfectly tailored to a vigilant and paranoid home-owner. This matters. Because being watched by the state is one thing, but being watched by your neighbours invites myriad more questions. In this second essay, we present a WhatsApp case study from South Africa. Admittedly it’s an extreme one, couched in a violent history of racial segregation.

We arrive in a leafy, affluent neighbourhood in north-western Johannesburg, the largest city in South Africa. Klasien and I are here to interview Mariette* (*not her real name) about her WhatsApp group. Unlike many of the residents in this area, we are on foot slowly making our way to Mariette’s house, taking our time to get to know the neighbourhood. The views from this suburb are impressive; it has a clear vantage point, located on a small hilltop overlooking the city. Here, the house prices are some of the highest in Johannesburg. Browsing local real estate advertisements you’ll come across words like ‘those lucky enough’ to own property in this ‘enviable location’, or ‘best kept secret’. Properties in the neighbourhood have high-perimeter walls and giant Jacaranda trees cast shade over manicured gardens. The streets are quiet and neighbours walk their dogs and children ride their bicycles. To us, this Johannesburg neighbourhood seems pretty idyllic.

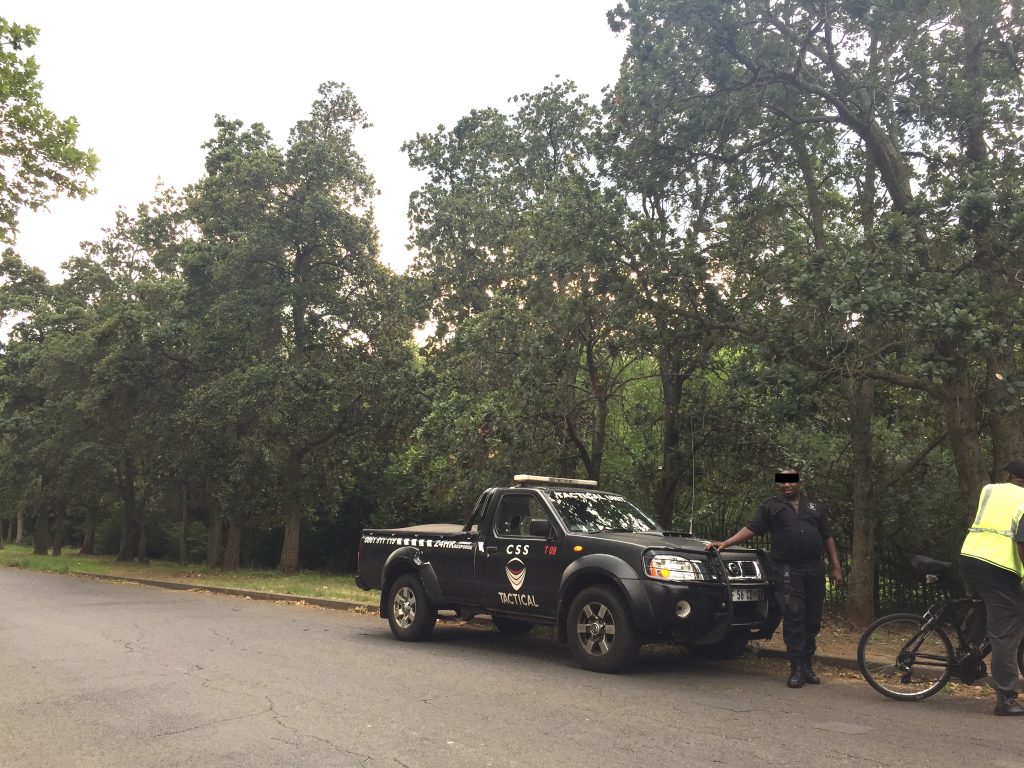

This idyllic setting comes at a price though. There is an omnipresent private security company that patrols the streets of the neighbourhood in large black utility vehicles fitted with enormous spotlights. We notice these, they are hard to miss, lingering slowly as they cruise up and down the streets. Paid for by the neighbours, these security vehicles scan the area for any suspicious activity. For a short while the driver even seems to trail us, we are out of place and walking too slowly it seems. Mariette’s neighbourhood is enclosed, which is not unusual in Johannesburg. This means there is only one street entrance for all cars. With permission from the city of Johannesburg, the residents have paid to erect a large palisade fence that closes off all other entrances to the suburb in an effort to prevent crime. A small number of pedestrian gates are left unlocked during the day. The sole remaining traffic entrance is fitted with a security-controlled boom where a guard is stationed 24 hours a day. When we arrive at the boom, we have to declare ourselves and let the guard know that we’re coming to see Mariette.

For a short while the driver even seems to trail us, we are out of place and walking too slowly it seems.

But alongside the security boom, ancient trees, beautifully trimmed lawns and driveways, lies another layer of urban infrastructure here: an electronic layer of communication. The neighbourhood has an active WhatsApp group with about 180 households where residents and the security patrol-unit share information with each other and note anything out of the ordinary. We meet Mariette in her spacious home overlooking Johannesburg’s much-loved urban forest. She is the admin of the neighbourhood’s WhatsApp group. Her job is to moderate and direct conversation between group members. Mariette has a very calm and assertive energy, which is probably why the group voted her to manage their communication. Hailing from a financial background, Mariette used to analyse risk for a living and is adept at making calculated decisions for the best possible outcomes. She exudes an air of decisiveness and resolution in her communication. These are handy attributes in a group admin, who often has to quickly negotiate very complex neighbourhood dynamics.

the entrance to the neighbourhood

Mariette starts our conversation by recounting a story of how neighbours in her area used to introduce themselves to the neighbourhood in the past, decades before the start of the WhatsApp group. Usually an invitation was extended to the wife of the new couple to join a few ladies for afternoon tea. Using a trusted neighbourhood ritual involving milk tart and Rooibos tea, the ladies would gently exchange questions and welcome the newest resident. The rituals and gender dynamics have certainly changed since then. As Mariette describes, “Now, people introduce themselves on the WhatsApp group and we all chime in to say hello and answer any questions they might have. There are some people I talk to quite often in the group but I’ve never met them. If they walked past me in the street I just wouldn’t recognise them”.

“There are some people I talk to quite often in the group but I’ve never met them. If they walked past me in the street I just wouldn’t recognise them”

Mariette’s neighbourhood WhatsApp group was formed during a crime wave in their area in 2013. The year the group formed, neighbours reported 13 burglaries, 17 robberies and 10 car thefts to their local police station. Mariette describes how in some of these instances, neighbours cried out to their WhatsApp group for help, fearful of being attacked in their homes. Group members reported a car hijacking in the neighbourhood that involved children. Neighbours anxiously recounted scenes of a housebreaking. Mariette describes how the WhatsApp group became a de facto panic button as neighbours turned to the group first, before their security company or even the police, when anything happened. Often, messages were sent to the group to verify strange sounds and account for cars and people in the neighbourhood. Did you hear that? Was it a firecracker or a gunshot? However, in the early set-up phase of the group, members also expressed feelings of safety. Members remarked that they felt at ease already knowing that others were ‘on watch’. Group members often made themselves available to others in the neighbourhood. In one instance Mariette describes how a neighbour who wasn’t home asked if someone could check on their house when the alarm sounded. Various group members replied to this call for help, showing the group’s responsiveness and care.

Security in the streets of the neighbourhood

More than twenty years after South Africa’s first democratic election in 1994, artist William Kentridge observes that “Race and class divisions are with us as strongly as ever. A happy ending is by no means assured. There is a daily, low-grade civil war at every stop street. The incidences of racial, verbal and physical abuse alert us to the rages that still burn inside. They are shameful to all of us”. Kentridge names some of the central issues that exist in contemporary South African society and often find expression in the context of neighbourhoods and their WhatsApp groups. The most glaring of these issues is race relations, which, when set against a historical backdrop of institutional racial segregation under Apartheid in South Africa, presents a very unique case study. Writing in the TimesLive newspaper in 2014, South African journalist Tanya Farber exposed the coded language that many South Africans use in their WhatsApp groups that have become taken for granted as part of a system of civilian policing. Farber described a mode of racial profiling in neighbourhood WhatsApp groups that employs phrases like ‘bravo male’ or abbreviations such as ‘BM’ to talk about black males or ‘CM’ to talk about coloured males. Similarly, burglaries are described as ‘home invasions’ adding to a military style vocabulary that has become routine in these groups. Unsurprisingly, Mariette’s group has also adopted this style of language which is often initiated by their private security company who are also in the WhatsApp group.

South African journalist Tanya Farber exposed the coded language that many South Africans use in their WhatsApp groups that have become taken for granted as part of a system of civilian policing.

Notably, Mariette’s neighbourhood has four times the median annual income of its closest neighbouring district, where 23% of that area’s population have no household income. Neighbourhoods in South Africa that can afford to employ private security companies have 24-hour patrols, guarding their streets and houses. These private security companies, alongside residents, have come to determine how notions of space and movement are reconfigured in the neighbourhood, facilitated by the neighbourhood’s WhatsApp group.

This reconfiguration creates a certain privatisation of urban space, which doesn’t only happen in South Africa but with the country’s history this phenomenon can be more uniquely considered. As a result of the pressure of maintaining a presence in all neighbourhoods of post-apartheid South Africa in 1994, police were redistributed to previously under-policed black areas. As a result, wealthier, formerly whites-only neighbourhoods turned to private security to manage access control and crime prevention. This form of privatisation has contributed to a particular narrative around space where streets and neighbourhoods are often treated as a small territory. Neighbours start to govern that territory as their own, warding off those who they deem to be strangers and don’t belong, thereby securing ‘their neighbourhood’.

The gate closing off the neighbourhood in Johannesburg

The feminist theorist Sara Ahmed wrote that a neighbourhood can enter public conversations as an entity ‘already in crisis’. In the context of Mariette’s neighbourhood, this idea is easily understood by the legacy of racial segregation and the violence of the apartheid era that still haunts public spaces. Ahmed goes further to suggest that the neighbourhood is not simply a space defined by economic and class commonalities. Beyond these measures the neighbourhood is also bound together as a site of collective panic. An incident in Mariette’s neighbourhood perfectly illustrates this point.

A stranger, allegedly drunk and stoned, stumbled into the suburb. A neighbour spotted the man and alerted the neighbourhood via the WhatsApp group. The chat lit up as neighbours reacted strongly to the stranger in their space. They coordinated a plan of action via the chat, to remove him from their streets. Using a mixture of CCTV camera footage and the WhatsApp group chat, neighbours posted pictures and pinpointed the movements of the man as he walked through the streets and passed by their homes. Panic escalated quickly and so did the neighbourhood’s reactions. A young neighbour volunteered himself to physically remove the man from the neighbourhood, grabbing a paintball gun for protection. He was joined by another neighbour who eagerly reassured the group they had the situation under control.

The stranger had not threatened or disturbed anyone in the neighbourhood but when the men caught up with him they shot him with the paintball gun. Lying stunned on the floor, the “stranger” was held down by the duo while the group called their security company for back up. When the security officers arrived they then tasered the man. The events were all posted into the group chat and various neighbours commented. One neighbour excitedly remarked that she wished she could have been there to witness the action. Neighbours congratulated the men for their bravery. Later the South African police arrived and released the man, to the dismay of the group. The police warned the neighbours not to take matters into their own hands. The neighbours were incredulous and the group buzzed with messages of irritation and frustration.

The WhatsApp conversations of Mariette’s neighbourhood are, in part, a reflection of the general state of insecurity and fear about crime in South Africa. The country’s crime statistics are amongst the highest in the world. In one year, from 2019-2020, 2.3 million South Africans experienced a house breaking or burglary. It seems many South Africans are willing to give up certain freedoms, like privacy, open access and free movement in exchange for tighter controls and constant surveillance if it means they feel safer. The results show across the country in fortified neighbourhoods with vigilant WhatsApp groups using military codes to communicate with each other. It is important to emphasise that fear of crime in South Africa is not unique to white South Africans. It is felt across all socioeconomic and race groups. However, South African researchers argue that this enclave living in enclosed neighbourhoods breeds more feelings of mistrust and paranoia in neighbourhoods, as residents limit social mixing. The local neighbourhood WhatsApp group reveals the panicky potential of neighbourhoods driven both by actual crime and the fear of crime.

The local neighbourhood WhatsApp group reveals the panicky potential of neighbourhoods driven both by actual crime and the fear of crime.

In Mariette’s neighbourhood fear and paranoia are circulated through WhatsApp and seem to accelerate the urgency of the security situation and amplify the perceived notion of neighbourhood precarity. This fear and anxiety may also relate to how the neighbourhood perceives a threat. Canadian media theorist Brian Massumi argues that fear can be seen to enlarge any existing or implied threat. Massumi claims that in this way, emotions can be elevated above facts or even come to stand in for them. He writes that, ‘The felt reality of the threat is so superlatively real that it translates into a felt certainty about the world, even in the absence of other grounding for it in the observable world …. The affect-driven logic of the would-have/could-have is what discursively ensures that the actual facts will always remain an open case, for all pre-emptive intents and purposes’.

This is an important point, that fear and paranoia can be circulated in groups and can be exaggerated along the way. Like Massumi suggests, these emotions may even be privileged above the facts. In more extreme contexts, this can have disastrous consequences. In 2018 in India’s north-eastern state of Assam, two men were killed by a mob of local residents. The men, Nilotpal Das and Abijeet Nath, an audio engineer and a digital artist respectively, had stopped in a village to ask for directions. Unbeknownst to Das and Nath, the village was in a state of hyper-vigilance towards outsiders after a series of child kidnappings in the area. A series of disturbing WhatsApp messages had been circulating amongst villagers festering a deep sense of suspicion and paranoia. The mob suspected Das and Nath were the kidnappers and the two were subsequently beaten to death. The killing was also filmed on a mobile phone and later circulated on WhatsApp amongst locals. The police subsequently confirmed that the kidnapping messages, which contained a video of a child purportedly being snatched, were entirely fake.

Dr. Natalie Dixon is an INC research fellow and founder & cultural insights director at affect lab, a women-led creative studio and research practice based in Amsterdam. Her work explores questions of gender, race and belonging through the lens of technology. Alongside her creative partner, Klasien van de Zandschulp, they are the creators of Good Neighbours.