Illustrators, designers and other creatives gathered in a skatepark in Breda last month to learn from each other and discuss the realities of working in precarious conditions where disciplines merge, creativity flows, and we all negotiate ways to stay afloat – financially and emotionally. What came out of the two-day event?

Gathering energy

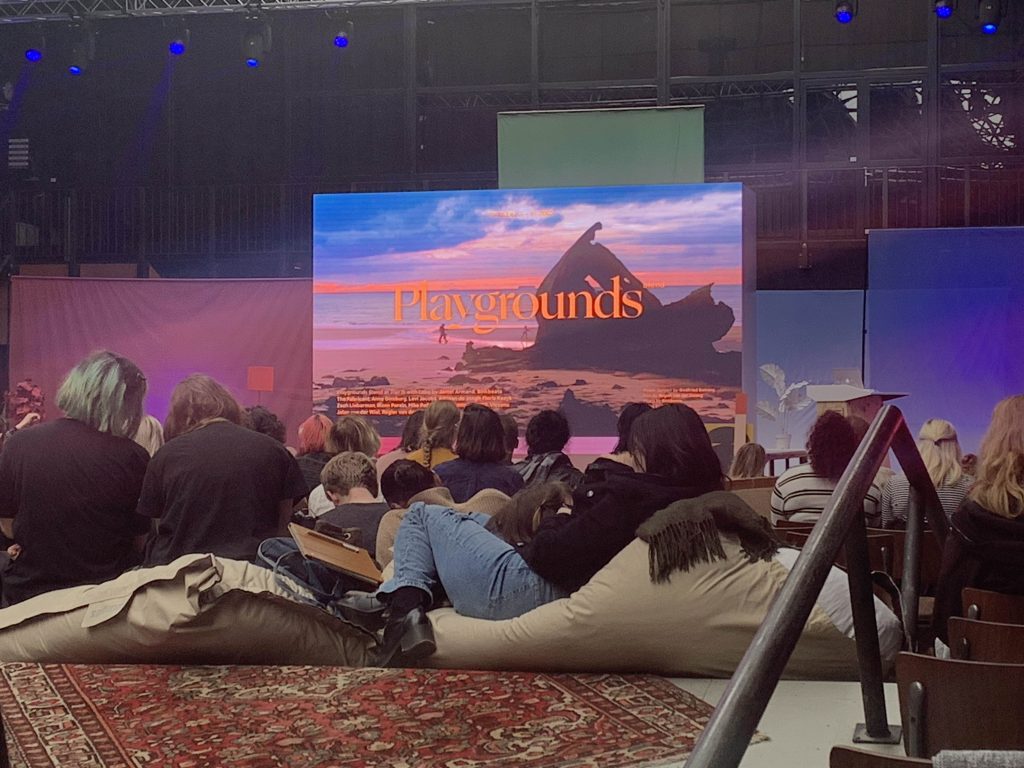

The spacious PIER-15 building and its surrounding area adapted well to hosting artist talks, interactive installations, and an exhibition, “Post-Digital Hairiness with Furry Friends and Foes.” Palpable excitement permeated the air as more attendees found their seats and bean bags, waiting for the talks to start.

A mesmerising video of two lights dancing across landscapes of the French riviera marked the beginning of the festival. The whimsical images contrasted Binkbeat’s musical backdrop nicely, making me wonder what might come next. I was not sure what to expect, as some of the content about Blend online appeared a little bit commercial and even corporate.

I came to find that Blend instead offers a series of candid and touching artist talks that recognise the commercial dimension of their work, but for the most part approach it with nuance and honesty. Coming from different areas of expertise like game design, product design, animation, drawing, painting, and music, the speakers touched on similar themes of failure, money, and inspiration. The co-creator Suzanne Reitdijk tells me this is an important aspect of the festival: “The failures are just as important as the successes. It’s something our audience needs to hear, and it isn’t said to them often.” This emphasis on the complexity of the creative process allows Blend to dodge self-congratulation and enter a space of authenticity and curiosity.

Demystifying the process

Artist Jamel Armand strolls on stage with a big brush in hand and begins to create an action painting as Playgrounds founder Leon van Rooij asks him questions about his process and journey as an artist. Armand stresses the importance of doing and talks about the dangers of overthinking your work. In a way, this echoes Rogier van der Zwaag’s talk. He discussed the process of trial-and-error that eventually led him to making the Blend opening sequence with the floating lights on the French riviera. The speakers encourage the audience to embrace intuitive work and test out concepts instead of dwelling on them. It is a bit simplistic, but maybe that’s exactly what we needed to hear. Overthinking does stifle creativity. But how can you get out of a rut?

Artist Jamel Armand at work. Photographer: Willeke Machiels.

I look around and see many young faces observing the talks intently, drawing or doodling as they listen, and readying their questions. After their talks, the speakers stay in the space. Conversations continue in this way. Suzanne tells me: “We are a festival and an organisation who creates programmes for the industry, for creatives. It’s really about inspiring makers and networking and giving them a moment where they can meet each other and catch up and see nice artworks of others. We don’t charge hundreds of euros to attend. We are open for those just starting out. There are gaps between art school and whatever happens next and we respond to that with our programme.”

Even though I do not belong to this target audience of Blend, I appreciate the honesty permeating the event and relate to the struggles of creative blocks and the over-intellectualisation of the creative process. I feel inspired to start doing.

Italian artist and illustrator Lisa Rampilli shares my excitement over the atmosphere at Blend: “I have a good impression that the young people here are very genuine and straightforward in the best way, they are direct and instinctive.” As an analogue artist, Lisa was certainly outnumbered by the presence of the digital at the festival, but spoke with conviction about the importance of allowing the hand-made and digital to meet.

Lisa Rampilli talks about her drawings and paintings inspired by nature. Photographer: Willeke Machiels.

Harnessing design

Something which felt as if it was missing was a focus on critical design. I understand the importance of being transparent about the realities of being a maker and the need to do commercial jobs to support other projects. Many of the speakers spoke to this balance with eloquence and nuance. But we have to remember that makers have the responsibility, when putting products and experiences into the world, to consider not just the commercial and creative dimensions of their work, but also the social and cultural impact it makes.

Consider this case study: it is useful to point out and consider the environmental toll of fashion, especially fast fashion, and to seek out alternatives. But if we engage with the concept of digital fashion uncritically and assume that everybody has equal access to it and would be equally interested in such a thing, we end up unable to engage with the challenges of sustainable fashion in a meaningful way. The duo of “The Fabricant” spoke with passion about curbing the negative effects on the environment of the fashion industry. However, they could’ve gone further in identifying consumerist and capitalist modes of production as contributors to the waste and obsolescence in fashion. Tom Robertson provides an in-depth analysis of digital fashion in his recent Longform.

This quest of increasing the accessibility of digital fashion replaces what could’ve been a consideration of the pitfalls we encounter when constructing identity online. When we ignore the corporate interests behind our obsession with virtual self-image, we can’t progress past it.

Marijke De Roover’s print from series “Niche Memes for Frustrated Queers,” 2019-20 currently on show at IMPAKT Centre in Utrecht.

Searching for authentic perspectives

Later that afternoon, director and animator Anna Ginsburg discussed social responsibility in her work with self-awareness, wit, and warmth. She touched on the balance between paid work and more fulfilling personal projects, and shared personal stories that added urgency to her explorations of bodies and sexuality in her work. I would have loved to see more stories like her, also from makers of different backgrounds. Young attendees of Blend can do so much more with their studies and artistic practice if they encounter stories about design and social responsibility from different and diverse angles.

While the scheduled talks offered some insight into the artists’ processes and journeys, I was just as inspired by conversations that took place amongst the attendees and volunteers of Blend; a vibrant group of people keen to exchange their niche interests and creative ambitions. These unexpected interactions made me realise that what I had been missing since last year was the opportunity to sit down at the table with new people and talk about our creative interests and plans face-to-face. Without this kind of a support network (even if it’s temporary) creativity cannot flourish.

Anna Ginsburg. Photographer: Willeke Machiels.

Blend provided an entertaining and thought-provoking selection of talks and experiences tailored to the needs of emerging artists and makers. It is a useful starting point from which attendees can make new connections and do their own research, filling in any gaps, like more critical approaches to the modes of production today. After spending two full days in Breda, it comes to me that the strength of the festival is in the people behind-the-scenes. Young creatives need opportunities to speak with more established artists and makers in a setting that demystifies the creative process. Blend provides just that, strengthening my conviction that we thrive when we learn from each other in stimulating (physical/digital/hybrid) settings.

A lot of us might feel over-digitized and overstimulated, but we are still capable of so much connection in the physical world. Technology doesn’t have to stop us from being with each other in a meaningful way. Blending physical and digital allows for new combinations and exchanges; both in the creative industries, and in interpersonal relationships. It starts with an open mind and a curiosity about other people.

Playgrounds runs a year-round programme of festivals, events, and gatherings, both in the physical and digital sphere. More info here.