This is it now, this is what life is all about now, looking at screens, I’ve just accepted it, my friend Jordi told me, while we each look at our monitors, comparing our screen time. He unabashedly told me his phone screen time is 4 hours a day, which is a lot, I think, but a quick google search shows it is just about average. And this statistic excludes computer screen time, which potentially fills the rest of our waking life. But really, it’s true, many of us spend our lives and build our skills and subsequently identities behind screens.

I am not trying to write another one of those texts about how negatively our lives are affected by social media. This is it now. One must go out of their way to construct a life that doesn’t hinge on screen time. And it’s not really about screen time in itself, it’s more that the time offline bleeds into the time online. The border between the two, what was before sharply separated worlds that we experienced in the pre-2012 internet era, have now progressively, naturally, and irreversibly, merged.

The Czech design duo based in the Netherlands called The Rodina agree. They describe one of their projects titled States of Play: Roleplay Reality, as dealing with how role-play can be used as a tactic to reflect, contest and move beyond real-world power structures. No longer understood merely as a place of escape, the game real and the real world have collided. The roles we play, both on and offline, reflect and shape our realities.1

There is much talk of avatars and online role-play, how it offers a sense of freedom we cannot experience in our drab, socially aware, and awkward real realities, but I think the roles we perform in the digital spheres are just as legitimate identity signifiers as our projections in real life. The argument that says: “Hey! Don’t judge people by their online personas!”, is moot to me, since no matter how divergent the IRL and online versions of ourselves are, they both showcase certain needs and wishes of how we want to be perceived – and often the same ones. The cringe factor enters when our online identity has been too obviously pruned, and our needs and wishes about how we want to be perceived are somehow too apparent. At the same time, because we all do the pruning to some extent, there is a sweet, wide acceptance and even nurturing understanding towards our online shaping. In fact, some of the most successful social media accounts are those that are intensely and obviously aesthetically trimmed.

The accepted sociological position that the self is made up of multiple identities, each of which exists within a separate network of others who hold particular expectations, is morphed in the post-internet era, where the identities we once separately held and enacted in specific and diverse contexts have now merged. Not only that, but ‘weak-tie’ maintenance across social media in what researchers call social media collusion is key in gathering and maintaining social capital.2 Different media are obviously dedicated to different audiences; LinkedIn to your professional network, Instagram, Twitter to your professional and personal network, and Facebook perhaps more to your personal network. The ability to transcend network walls is instrumental in obtaining social, informational, and thus material resources. We will return to this later. But for now, I can’t escape the feeling that the purposeful display of our secret and subtle variations on a platter of our chosen social media is in itself a bit cringe-worthy.

And I wonder if, when I use the word cringe, I actually mean intimate. Because isn’t intimacy really what this display of our inner needs and multiple selves is?

When in an intimate relationship, our partner or friend knows these sides of us and accepts the awkward collisions, irregularities, and projections the multitudes of self inherently bring along.

In the online dictionary, intimacy is defined as

a; close familiarity or friendship

b; cosy and relaxed atmosphere

c; sexual intercourse

I find these definitions wonderfully apt for the ways our online personas interact with and maintain the ‘weak-tie’ relationships of our digital world, but also the relationship with the media itself. It is a very intimate relationship indeed.

The media is something to be addressed not only because it offers an extension of ourselves, but also because it represents a virtual space we inhabit, with pillars, arches, and windows, not unlike the physical temples we enter on our trips to Rome and Granada to witness the triumphs and testaments of history. The media presents a very real and tangible architectural space. It constitutes a space to the extent that whenever I have deactivated my Instagram account in the past, while I did miss the content I consumed and the dopamine triggered at the base of my brain by the likes and views received, I primarily missed the architecture of the space that Instagram represented to me.

The longing was alleviated by just entering and scrolling through my friends’ accounts when borrowing their phones. It was more the structure of the media than the content that was lacking in my life. One could almost call it a familiar, cosy, and relaxed structure. Not unlike the feeling of slight arousal, the feeling of stroking a familiar body.

Social media theorist Nathan Jurgenson agrees, writing that there is “nothing anti-human about technology: the smartphone that you rub and take to bed is a technology of flesh. Information penetrates the body in an increasingly more intimate way.” As digital sound artist Holly Herndon puts it: “how we interact with these technologies is altering our physical and emotive states, and in turn, technologies are responding to these developments.”3

The closeness of digital space offers a welcoming environment for the unruly extensions of ourselves. Perhaps the welcoming aspect and the magic of image extension and control is the most appealing feature of the social media sphere. The devices we use are our vessels of creation in some way. Herndon explains: “my laptop is an extension of my memory and self, it is a conduit to the people I care about and, in many ways, retains more knowledge about me in one moment than I can muster.”4 This conduit is double-sided, a link between members in a symbiotic relationship. Again, this conduit functions not only between the creator or persona and their followers but also between the creator or persona and the actual technology.

As demonstrated in the case of Arca, a digital sound artist but also a trendsetting image-maker, physicality and information are perpetually enmeshed and co-determining. The physical impact of digital technology on her body marks her transformative and futuristic aesthetic, and by extension, her identity. Or is it the other way around? This question can only be answered by skewing our lens toward a more synthetic understanding of media, bodies, technology, and society. The multimodality of the internet dictates the intermedial formats of post-internet content creation and enables ways in which our online and IRL personas flesh out.

Flesh out is the softer way of putting what we could easily call design. The intimate, familiar, and welcoming environment of the digital sphere, combined with the very real transformation of the economy into what is called the ‘attention economy’, has set a stage that doubles as an exhibition space. Individuals appear as both artists and self-produced works of art. Your social presence is designed in a way that forms your identity, complete with political leanings, aesthetic preferences, and social orbits of opportunities. As I previously mentioned, the ability to successfully execute social media collusion, ‘weak-tie’ maintenance and social capital amassment influences our informational and material resources. Within the attention economy, the amount of recognition our personas attract enables us to network more successfully and gain actual career development opportunities that result in the expansion of our financial capital as well. The societal pressure to design ourselves prioritizes the possibility of commercial growth. This phenomenon, according to cultural critic Mark Fisher, can be slotted under the effect of ‘business ontology’: the pervasive and fatalistic view that everything should be treated as a commercial enterprise under capitalism.5

Fisher is most certainly not part of the post-internet generation, a fact which positions him in a dark corner from which he evaluates our commodified and self-designed identities as nothing more than resources to be exploited. Though a valid critique, Fisher fails to skew his lens towards the fusion of technology and society and invalidates the countless individuals who attain community, freedom, and variety of self-expression through the multiple modalities the internet offers. This is it now.

For the post-internet generation, the intimate worlds which open up through online identity development transcend the potential of designing ourselves as a commercial enterprise. I would even maintain that the sense of value we stand to gain from the design and development of our online self (selves) is much deeper than mere market value. This deeper value is that which causes the addiction to and an inherently narcissistic twist of many of our internet identities, with the process of self-branding directed toward intuitively social rather than market gains.

The Rodina, this artist duo to whom I referred earlier, made a project titled Parade which explores narcissism in today’s world. “It questions the ecstasy of parading the self to the world, attains the image of the ideal self as a means of gaining a sense of value, distinction, or immortality.„6 The project entails an electronic pop video that creates a musical image of the future – a rainy fantasy world as a vision of a globalized culture stream. The video is an experiential depiction of the need for interaction and approval, a parallel to a very different but essentially connected project by British artist Mark Farid titled the Poisonous Antidote. He broadcasts every facet of his online presence in real-time for an entire month, including locations, pictures, videos, personal and professional emails, text messages, web browsing, phone calls, and all social media feeds and chats. He maintains that his narcissistic need for approval is the urge that led him to willingly relinquish his internet privacy in exchange for perceived social stardom.

Throughout the months of digital exposure, he discovered that he consciously and unconsciously adjusted his behaviour to the presence of the spectator, visiting pornography and sports news sites less often than he usually would, keeping senseless internet browsing to a minimum, and going on more walks in the park. He found himself conforming to his insecurities, rooted in societal ideologies, doing what he felt he was meant to be doing, and feeling validated by the knowledge that people could see this.7 Farid constantly judged his actions and options through the gaze of the outsider or general society. These micro-adjustments are clearly and consistently present throughout the building of our online identities, which is when the gratifying, intimate light of self-expression and formation dims.

Farid invested labour in his month of exposure to minimize the mass of secret activities we all do online, some so sickeningly narcissistic that even the inside spectator cringes at this unwanted intimacy and confrontation with the dark underbelly of existence as post-human web creatures. The countless open tabs, the self-indulging google questions, the bizarre web searches, the vile Reddit threads, the obscure Wiki searches, and in my case, horribly banal gossip sites and obsessive reading about cannibalistic serial killers. These activities are not so far removed from our photo booth, filled with pouted and contorted faces, this super-secret side of you that you adore and deplore at the same time. This weird fascination with home pornography and filming yourself to see what you appear like from the outside. Only bits of this content leaks through to your constructed online identity, but leak it does. What is therefore present in any online construction is the sort of dirty inner spectator and this possibly less forgiving outside spectator, for whom we shape, adjust, flesh out and design.

The outside spectator is especially important in the attempts to build sexual and intimate relations online. As more of our lives merge with the digital world, it is implicit that the way we form partnerships also moves to the online realm. Dating sites such as Tinder, Bumble, Hinge and Grinder have become a prolific way for people to meet their significant others, with a Stanford 2017 report showing that more people in a heterosexual relationship meet their partners online than offline.8 Sometimes though, relationships are formed in the online sphere and remain there. Through visual/auditory stimulation and the symbolic sensation of contact, individuals can experience the palpable presence of another person, despite never spending IRL time together.

On online dating sites, the effectiveness of self-branding is obviously essential in representing ourselves to prospective partners. Despite everyone being seemingly sick of online dating, it continues to be a popular way in which we search for partners. But it’s difficult. The awkward moment when we swipe someone in our social sphere whom we might want to date, and we match, and then never talk when we see each other in random social contexts. Jesus. Or worse, when you swipe right (the want direction) for someone within your social context and never get the match. Funnily enough, this love-hate relationship with the online medium for the purpose of dating is actually bringing back the phenomenon of blind dates, as it returns the element of mystique that is difficult to attain in the digital world. Once we settle on a potential date, we already have enough information about the chosen one to form a pretty coherent impression of who this person is. This idea affects our IRL impression to the degree that regardless of how we vibe in the offline realm, the sediment of our first digital notion remains.

I have absolutely rejected people from online dating apps once I checked out their social media accounts and jumped to conclusions regarding their intimate online projections, making a judgment and never looking back. Similarly, I have met people whom I found annoying or underwhelming, and then my opinion was adjusted once I stalked them on social media and liked their aesthetic or was impressed by how many quality followers they have.

Despite sharing intimate online identities with a mass of prospective lovers, our involvement can be completely controlled and regulated, potentially even anonymous. The control over your communication, the constant possibility to just ghost someone and disappear as well as the common practice of cultivating many simultaneous options is labelled as ‘risk aversion’. ‘Risk aversion’ suggests that we are incessantly in the process of constructing, adjusting, and developing the unions we form with one another, with the awareness that they can be transient. Mediated communication, the trend towards plastic sexuality, and the deconstruction of heteronormative standards lead to relationships becoming more ephemeral with the expectations of life-long partnerships decreasing. The Polish philosopher Zygmund Bauman poetically described this state as liquid: “In a liquid modern life there are no permanent bonds, and any that we take up for a time must be tied loosely so that they can be untied again, as quickly and as effortlessly as possible, when circumstances change – as they surely will in our liquid modern society, over and over again.”9

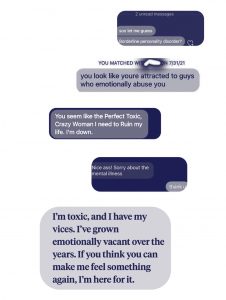

Often, even communication on online dating platforms seems aimed at transient relationships. It is not uncommon to get the feeling that there isn’t much emotional investment or even an expectation in attempts at communicating and flirting online (I mean, how many variations of ‘hey.’ can we suffer through?). There is actually an IG account, called beam_me_up_softboi, which collects screenshots of embarrassingly bad short exchanges and one-line attempts from online dating platforms, all of which seem to be aimed at very transient connections, mostly from men towards women. “They can’t be serious?”, we ask ourselves while scrolling through this barrage of failed flirts. The examples seem to showcase a purposefully distanced and vapid attitude toward desire, affection and mental health. And although masked in a sometimes violent and often offensive sexual skin, we can’t escape the feeling that these are self-sabotaging, thinly veiled attempts at online intimacy and connection. Self-sabotaging precisely in that they showcase such compromised versions of the self, as if to say: “We cannot get hurt if we invite rejection.”

These chats are written in such a manner that they epitomize ‘risk aversion’ in practice by displaying a seeming distance to deep emotional investment, despite referring to matters that are in fact very primordial and needs that are real. This combination is a common one for the digital realm, flaunting and casualizing serious concerns into memefied conglomerations of pop culture.

I would rather describe ‘risk aversion’ as this odd internet humour that has developed, this super dark irony about our late-capitalist digital existence, which provides a barrier between the inherent intimacy of our online identities and rejection. An example is the IG account afffirmations with almost a million followers, but check that out on your own time.

Bauman, however, describes the ‘risk aversion’ we practice and the transiency of contemporary relations as another symptom of the ‘business ontology’; “Partnerships are increasingly seen through the prism of promises and expectations, and as a kind of product for consumers: satisfaction on the spot, and if not fully satisfied, return the product to the shop or replace it with a new and improved one!”10

The infrastructural mechanism behind dating apps does indeed encourage the expendability of individuals with the incessant swiping of the intimate projections of people in our surroundings. The feeling of a never-ending line of options is not false, and many of my friends frantically swipe Tinder profiles, lingering on each profile for a second if not less, relying on their intuitive instinct to help them manoeuvre the dizzying number of individuals ‘de-humanized’ into choices. We talk of this, my friends and I, confide in each other about the way we judge individuals on these apps and how frightening the swiping aspect really is. We do so in a detached and disheartened and witty way, once again practicing the post-internet humourized emotional distance towards the issues that plague our lives.

More proof that technology and social habits, in this case, love, are co-determining. The way the apps are built, and the amount of visual information circulating, influence how we perceive our dating options. We know this anyway, but Bauman also posits; “There is a universal comparison and you don’t just compare yourself with the people next door, you compare yourself to people all over the world and with what is being presented as the decent, proper and dignified life.”11 I think it is partially this comparison thing, which makes our standards so oddly morphed, that leads us to search not for our private partner in crime, but for our public partner, one that will fit all the unspoken standards of society and the outside spectator. We seem much less inclined to take risks with our choice of partners, but continue to search for the cool boy/girl, self-actualizing tropes we feel like we are politically deconstructing. It is not uncommon that we would prefer to be alone forever, rather than ‘settle’. Thus, this ultimately personal process is now publicized through the intimacy of online identity building and the presence of the outside spectator that influences the inside one.

Despite the mass of choices, the popularity of polyamory and the undeniable transiency of relationships in the post-digital era, temporary relationships are not what we necessarily wish for. Sociologists Beck and Beck-Gernsheim rightly find that we still idealize love. “Throughout one’s life course, relationships begin, dissolve and begin again in an endless pursuit of true love and fulfilment.”12

The idea of ‘risk aversion’ does not take into account the vulnerability of online dating. Because the process of self-branding for sex and love is, in fact, a very risky process, and a very serious business. The consistent academic downplaying and banalizing of the ultimately perilous activity of the online search for partners by comparing it to online shopping is problematic and shallow. What could be more intimate than displaying ourselves online with the automatic announcement of: “yo, I am high and dry here.” What could be more intimate than displaying our private selections of the photos we find sexy, or different ways of showcasing ourselves as desirable? The process of exhibiting our carefully constructed online roles, avatars, projections, and identities is a big, humiliating risk. No wonder we desensitize somewhat and practice that dry emotional detachment. We must.

If we look at them through a synthetic lens that attempts to perceive technology and society as symbiotic, then the roles we build online and the intimate identities we project are just as risky as, if not more, than any sort of IRL activities we engage in, precisely due to the pruned and precalculated aspect of it. Just because we have the possibility to opt out or ghost, to construct and adjust, just because we are faced with so many more options than before does not make online intimacy illegitimate or less heavy, messy, and slow-moving than real life. This is it now. Real game and real world have collided. We are out there, on the internet, growing and shaping ourselves and our identities in front of everyone’s very eyes. What could be riskier and more intimate than that?

—

If you want to know more about Klara Debeljak and her art practice, get in touch with her through her Instagram account.

—

Notes:

1 The Rodina, States of Play. The Rodina. therodina.com/states-of-play/.

4 Waugh, M. (2017), Ibid.

6 The Rodina (n.d.) Parade. The Rodina. therodina.com/parade/

9 Bauman, Z. (2000). Liquid modernity. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

11 Bauman, Z. (2000), Ibid.

12 Hobbs, M. & Owen, S. & Gerber, L. (2016), Ibid.