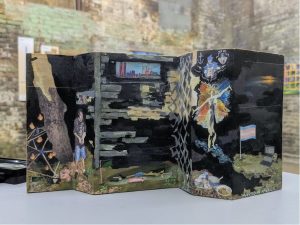

“Sketchbook” by Abbey Pusz, 2021

Abbey Pusz is an artist, writer, and video creator whose work surveys various iterations of utopian visions. From the promise/potential of digital spaces as an authentically democratic and participatory force to the organization of political movements and the persistent specter of the American Dream, her work both chronicles the lineage of and explores political potential through artistic and cultural expressions tied to the left— across on and offline spaces.

Pusz’s work spans sculpture, writing, research, and video. She is a founding member and co-director (2020-22) of the collective platform Do Not Research, an online community and publication for art and internet culture. What started as a COVID-born project consisting of independent Mark Fisher reading groups inspired by Joshua Citarella’s Discord chat soon expanded into a network of research, writing, visual art, posts, and IRL events.

In October 2023, Pusz co-released a new video project entitled “Spooky Castle” on the artist platform dis alongside Aaron Moulton and Jak Ritger, which investigates the histories of socially engaged art. Last spring, she curated “The Manic American Humanist Show” at the Public Works Administration in New York City. This year, “Spooky Castle” will be installed at POUSH in an exhibition entitled “I took a screenshot of the whole world” from January 12th to 19th, 2024.

After listening to a lecture she gave at the Unsound Festival in 2022 on the “post-internet” artist, I was curious to hear more from Pusz on how she uses vernaculars of visual internet cultures to construct new meanings and forms, especially concerning the “Extremely Online” phenomenon. Over Zoom, we discussed the potential of digital communities, irreverent Gen Alpha memes, and the political and aesthetic vision of the post-internet artist—where it came from and where Abbey envisions it heading.

SN: What led you to use the post-internet artist as a subject of your lecture?

Abbey Pusz: First of all, I don’t know if anyone knows what it is. Even the people in DNR were like what is the actual difference between net art and post-net art; they couldn’t come up with a definition. I watched some talks and lectures from 10-15 years ago that you can find about the post-internet that informed the lecture that I did. But it also was a way of describing the people who taught me. These are the people I’ve chosen to be my teachers. The quickest way I can say it is: different from other art movements, the artists aren’t directing the formal change in their art, more like the earth is moving underneath them, and therefore the art is changing, how we use technology changed. Then, the art changed formally. So, you can still make HTML-coded websites, but people have to deal with the reality of a website being coded less than what they had to do 20 years ago. You had to be a little bit of a technician to even use the computer in the 90s. So it made sense these artists were art technicians and art coders, but the internet kept moving, and so it kind of fell to the generation, the post-internet artists, to describe evolving internet culture and its politicization.

Unsound Presentation: D I G I T A L – L O C A L – The post Internet artists (Abbey Pusz)

SN: The term ‘Extremely Online’ has become so popular in the last few years, I’m curious to hear what that phrase means to you.

AP: I think there’s ‘Extremely Online’ in the way that it was being understood at the time of the alt-right, and that was hovering around the 2016 moment. I think where Josh [Citarella] was interested in was that there was a moment where that dissolved and then there were all these small idiosyncratic political movements happening online, and people having debates. Where I left off with that thought was when I curated the show at the Public Works Administration in New York, where it was like more than anything else, this is the culture we’ve inherited and that I grew up in. Yes, I grew up in Peekskill, New York, but I also grew up on the internet. There’s no distinction. It’s good to articulate it, give language to it, and, at its best, give an artistic observation of it.

With DNR, there was an attitude toward left accelerationism, which had this rediscovery of Marx as ‘pro-tech’ in the face of Capitalist Realism, it felt like the beginning of a positive project, an expanded horizon of what could be possible that met us where we are, with the tools we have at hand. There was a special emphasis on the prophetic power of Cybersin, a vision of industrial sensing that served its workers, not the continuation of Amazon.

I would say my current thinking on tech mostly hovers around that “this is where I grew up. This is what I’ve inherited.” As far as what I am currently thinking of leftist movements, I’m brought to the popular sentiment of “we have to get back to where we were,” but it’s kind of the wrong question; it’s like when were we a real left movement? We have to talk about the historical left and the historical avant-garde to move forward.

SN: For those who are less familiar, could you explain a little bit about what DNR is and about your role in it?

AB: Yeah, I was most involved in this project from 2020 to the beginning of this year when I curated that show at Public Works Administration. It started because we were watching Josh’s streams, and there was this appetite to keep hanging out with each other. It should be said these Twitch streams had this funny ability to act as a classroom and as entertainment: eat your vegetables first, then dessert. So we would watch a Mark Fisher lecture, and then we would do a political compass “personality quiz.”

After that, it kind of branched out in all these directions. Margo and I had become self-elected TAs, leading and following along with the syllabus Josh put out on his Patreon. We were doing so many things; we were doing this book club for maybe half a year before we were like, okay, to bring it to the next level, we have to do our homework. And so people started writing about this stuff that we were researching, and it was anything from Why are people interested in Starseeds? Can we come to this with an understanding of people feeling alienated in society rather than let’s just dunk on these people? Margo and I did the editing for Do Not Research as a web publication. When it was smaller, we were hands-on and everyone was to edit each other’s pieces and give feedback, and then it grew to accept more people, and it was a way in. If you published with us, you could get invited to the reading group.

SN: What is your relationship to posting?

AB: It was just fun to make my friends laugh. I want to give my friends the credit they deserve, they are so clever, funny, and agile. What I liked about DNR in its heyday was that these heavy theory concepts were getting metabolized by my friends, back into comedy, back into meme language in a way that didn’t feel too clunky. I thought it was weirdly elegant. Something else I always say is (and this extends to art as well): did memes get worse, or did we lose our political moment?

SN: How do you envision Gen Alpha memes will look like?

AB: It’s about irreverence. The thing about a meme is that it has a referential quality and how it points to something outside of itself. It might be the fact that it’s pointing to the fact that a meme gets posted a lot, and that’s why it becomes funny, or it’s pointing to some easter egg in Halo, and then it becomes funny. First, if you’re familiar with it, and then because you’re familiar with the meme, could be sufficient.

The thing about the Gen Alpha memes that’s awesome is that it has the feeling of pointing to something and having a reference to something, but it doesn’t matter. I was feeling like I needed to get my walker out, like, what is Skibidi? But actually, it doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter if you know fanum tax is from a Twitch streamer, you just have to enjoy the way it feels on your tongue.

SN: Why do you think Discord has become such a dominant space for fostering new communities?

AB: I think it’s the closed community thing, or the “Dark Forest,” as Caroline Busta popularized it. I come at it from a weird angle because I was too young to be in an arts scene when COVID happened, so this was also my first introduction to a “scene,” maybe I have stars in my eyes that other people maybe wouldn’t.

“Yankee Monument” by Emma Murray & “Lack Loop” by Tomi Faison – Image courtesy of PWA – photo credit: Courtney Kinnare – March 2023. Source: https://www.punctr.art/review-the-manic-american-humanist-show/

SN: Last spring, you curated the “The Manic American Humanist Show.” What was your inspiration, and how was that experience for you?

AP: That was to put a period on the lecture I did at Unsound. They feel like the same thing, kind of closing the book on that project, and it was something that I felt I needed to deal with. The COVID/BLM moment didn’t succeed in building a political alternative. But, I’m thankful because one of the other driving points in DNR was this belief in art as it is, art as it behaves, and retaining the dignity of art as art. I was disappointed by one thing but still excited by the other thing. I still feel like my peers make excellent artwork that fits well in a gallery space. I feel so glad I was able to close the book in that way.

SN: You recently released a new video on the platform dis. How did this project come together?

AP: We had a day and a half in Warsaw, and I had pitched them on this project a couple of months before to do a panel discussion while we were there. I had this funny idea of doing this creature-of-the-week style video to translate the taboo of mainstream liberal culture into a campy Pee Wee’s Playhouse-y space. That was all we needed. Jak made the mummy costume, put it in his bag, and brought it on the plane with him. [Aaron and Jak] did all the writing and created their characters. So, after that point, I was just thinking about the visual character of this space. […] It was a three-way split. They led the project, and the things I contributed were the graphics, and we did the set dressing. It was all done together.

Screenshot of “Spooky Castle” by Aaron Moulton, Jak Ritger, and Abbey Pusz, 2023. https://dis.art/

SN: How did the castle setting influence the project?

AP: What a crazy thing to have a “right-wing” art institution at all. One of Aaron’s driving points was that it doesn’t recommend any formal development in the art. It’s very strange. But what was being represented was this mirror image of the way art is produced in the Western world. It’s like they’re still doing performance art. It’s just creepy now, so that’s the Ujazdowski castle. That’s one thing Aaron is thinking about. Then he was also thinking about the history of the Soros centers, which were a 1990s interjection of money, technology, access, and entrance to the art world. That’s where biennales come from. So, he was kind of going full circle where the Ujazdowski castle is critiquing the forms of liberal art, still producing performance art anyway, and it also turns out that Eastern Europe had a strange opportunity in its democratizing wave to be the frontrunners of that kind of art. And that’s a story that doesn’t get told, but you see it in the works we discuss.

SN: Your video “You Can Do the Macarena to Any Song” is also featured in “Spooky Castle.” How did you become interested in the macarena as a unit for cultural transmission?

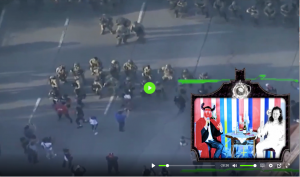

AP: I found the video of the BLM protestors doing the macarena with soldiers. Then, I started this project, and towards the end of doing it, I found the drone shot, which was like the 12 tanks that are around people. It was some crazy right-wing ranter ranting over the news. But it gave that perspective. One of the other strains of my practice is that I like thinking about how people move their bodies, and I liked that this could be this weird democratizing gesture. But it can bend in either direction. It’s not necessarily in service of a direct action, everybody-involved-participatory thing. It’s more about the calculation of who has more power. That’s the criticism that always gets brought against the millennial political sense globally, not just in American politics. If you’re playing a non-hierarchical game like eventually, whoever held power in the first place becomes reaffirmed is just going to keep going. You can kind of diffuse it in the immediate social space, and that’s compelling. It does feel good to dance with people.

Image from the “You Can Do the Macarena to Any Song” essay, Do Not Research, 2021 https://legacy.donotresearch.net/posts/you-can-do-the-macarena-to-any-song]

SN: Have you explored TikTok in your work concerning that idea of movement?

AP: One note on that: you get points for doing the macarena not because of your virtuosity or how great a dancer you are; you get points for knowing it. I was thinking about TikTok at the time. There are a lot of smaller videos I made that even have a kind of TikTok orientation to how the videos are made. I was thinking about that, but funnily, I didn’t have to include TikTok to speak to TikTok.

SN: Can you say more about networked spirituality?

AP: At the time, there was this turn towards networked spirituality and that we need to look outside of politics for transformation and look back inside ourselves. And that’s always something that’s happened; that’s the New Left but unaware of how it reproduces “tune in, drop out.” It’s also about self-transformation. It’s like, let’s just go inward, and that’s a perspective from people on the left. I have a criticism of it because it’s like also tinged with self-transformation through technology.

SN: As platforms become more regulated, where do you think we go from here?

AP: I would recommend a book by Ben Davis called “Art in the After-Culture.” It’s a series of essays. He explores this possibility of a continued need and the possibility of subcultures. He fast-forwards us to an even more hellish dystopian future. Again, there’s this political possibility to subcultures, which is the boat we’re all in. We’re waiting to see if this will be the time that everything flips.

“Margo in America” by Abbey Pusz, 2022

SN: What have you been reading lately?

AP: I’m reading Chris Cutrone’s “Death of the Millennial Left.” I also want to shout out being tutored by a friend in Chris Cutrone’s “Art and Politics” syllabus. Something else that I’ve read is Ben Lerner’s “10:04.” He’s a good offramp for anybody who has a question about that Utopian urge of Occupy.

SN: Are utopias still a significant source of inspiration for you?

AP: I would say so. I think particularly because of the way the millennial left thinks about it. I don’t know if I’m thinking as a Utopianist because I think when I wrote my bio, it was more related to accelerationism, like let’s just propose a positive project and apply that experiment to ourselves. Then, I think I stayed interested in it because the millennial left will stay interested in it. My standpoint is that I’ll always listen because I would like for these movements to work. But I also want to foster a historical consciousness.

Sara Nuta is a writer interested in media, internet culture, and digital spaces. She currently works as a lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Amsterdam.