Dietary practices and the digital landscape have always been entangled with one another. It seems like the visual practice of posting your food has existed as long as the affordance of posting photos online has existed, with heavily filtered pictures of plates and their contents being ubiquitous on almost any social media platform. Think of the #foodporn or #girldinner hashtags, for example. Food-visualization as a practice exists within several digital subcultures, too. Posting your plate can signify understanding or commitment to a particular subculture or political movement, especially if the contents of your plate are shocking and transgressive.

Such is the case for the raw meat subculture, which exists across several platforms but seems to be concentrated on Twitter/X. There is a good chance you’ve encountered it in the form of absurd food practices, such as eating raw animal organs or whole sticks of butter. Parts of the subculture exist as an extension of the ‘manosphere’, which is an umbrella term for digital spaces where right-wing, misogynistic, and ‘men’s rights’ rhetorics circulate[1]. The raw meat enthusiasts seek to transgress a mythologized hegemony that consists of ‘liberal’ elites who are, according to the subculture, attempting to undermine and dismantle masculinity through industrialized food practices and anti-masculinity doctrine.

Cluster of meals posted by several influencers

The subculture operates under the veil of health-consciousness, using this veil to disguise a much more sinister, reactionary politics. This is reflected by the rhetoric of its influencers, who supply and steer the discourse within the subculture. Subcultures like these are particularly relevant in a post-pandemic, unstable political landscape, wherein the corporeal has been repoliticized and doctrine of individual liberty and negative freedom is creeping back into more mainstream political discourses. The raw meat subculture is reactionary insofar as it is opposing the perceived loss of political agency of ‘masculine’, (mainly) Western men; attempting to regain this agency through the individual sovereignty of the body, which is concretized by corporeal practices (exercise, diet, lifestyle). These communities, in part, emanate out of the contemporary digital landscape, wherein individuals are overwhelmed by flows of data, which consequently leads to conspiracy narratives emerging as a way of anchoring oneself in the sea of information. A lot of reactionary subcultures not only supply these narratives, but construct a subsequent pipeline of political radicalization for its members. In our New Dark Age, flattened, simple, and reductive conspiratorial narratives dominate the (digital) cultural landscape. Our political discontent and desire for coherence leads to the desperate search for crystallization, a search which, more often than not, feels futile. Our precarious understanding of complex realities leaves us in a vulnerable position, a position that is exploited by narrational grifters and political fundamentalists, offering us the answers in their most seductive form: simple and conspiratorial narratives. Finally we can point the finger at something or someone, it could have been this easy all along!

The raw meat subculture and its influencer-grifters do exactly this: they construct a conspiracy-esque hegemony borrowing political values from the ‘manosphere’, wherein they posit that there is an agenda which seeks to emasculate Western men. They subsequently seek to transgress and challenge this constructed hegemony through visual, lifestyle, and dietary practices, which are displayed in digital spaces. They not only provide a scapegoat, but also a guide for resistance. The health oriented practices and doctrine of the raw meat subculture provides an accessible narrative for men that feel disenfranchised and seek to regain political agency, ultimately leading to radicalization and a rabbit hole of conspiratorial thinking, which funnels vulnerable subjects into right-wing conspiracy theory.

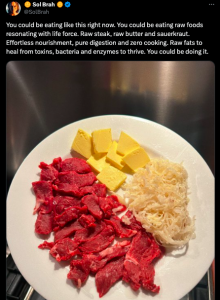

Tweet by @SolBrah

Most of the subculture can be found on Twitter, which seems to be the preferred platform for right-wing and reactionary influencers, mainly due to the perception of it being a ‘free-speech’ haven post-Muskification. Elon Musk’s acquisition of the platform and subsequent behavior, such as the consistent co-signing of right-wing accounts, and his unconditional, ‘patriotic’ approach to free speech, has shaped the contemporary perception of the platform. Through these recent transformations, Twitter has become even more deeply embedded with the kind of social-Darwinist Silicon Valley (and ultimately neoliberal) ideology that underscores individual liberty and unconditional free speech, and therefore has become the ideal destination for right-wing rhetoric.

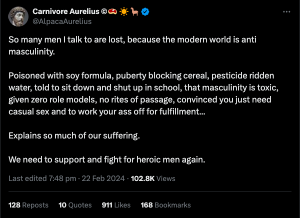

I identified eight ‘main’ influencers who seem to be most heavily involved in the subculture. Within this selection, there is a spectrum ranging from nutritional to political; the former being those whose primary concern seems to be dietary practices and lifestyle, with politics being secondary in their content, and the latter being primarily focused on politics, with dietary and lifestyle practices serving a more symbolic function. Influencers like @paulsaladinomd and @Mark_Sisson exist on the nutritional side of the spectrum, whereas influencers like @AlpacaAurelius and @CarnivoreSapien can be positioned on the political side, while people like @SolBrah and @SirBarefoot exist somewhere in the middle. Not only is this spectrum useful in categorizing influencers and their interests, but also in constructing a pipeline. For example, you can imagine that someone accesses these influencers through an interest in nutrition and health (perhaps already with a kernel of reactionary thought), and is then easily lead down a path of radicalization through the discovery of more explicitly reactionary influencers, often facilitated by Twitter itself, which provides accounts “You Might Like” on a sidebar. Posts by these influencers therefore also range from very literal, like screenshots of statistics and nutritional information or conventional meals, to more gestural and symbolic, such as grotesque raw meat plates, reactionary memes, and hyperbolically masculine bodies. Moreover, something which all influencers have in common is that they commodify and monetize part of their online presence. Dietary supplements, online courses, and/or books are ubiquitous on their feeds, and serve as obvious incentives for their online presence.

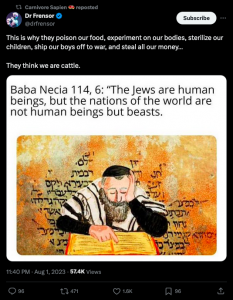

The influencers within the raw meat scene grift either products, narratives, or a combination of both. Because all influencers mentioned give and take from each other, they construct a sort of network across the nutritional-political spectrum, allowing users to freely navigate their ideas. Right-wing influencers often rely on collaboration to radicalize their audiences, as a milder influencer can simply retweet or reference more extreme content from another influencer[2], rather than saying it themselves. This leads users through a soft-radicalization process wherein they can ‘freely’ move from lifestyle and dietary content to explicit anti-semitic conspiracy theory.

Anti-semitic Tweet reposted by @CarnivoreSapien

Whereas influencers within the subculture post at different levels of political extremity, posting the body is an overarching trend. All of the aforementioned influencers are men that essentialize a gender binary and, similarly to men in the ‘manosphere’, present masculinity as something “powerful, dominant and authoritative”[3] and, moreover, as something which is actively being threatened in the Western political and cultural landscape. Posting a hyperbolically masculine body that adheres to conventions of attractiveness and health serves as a token of commitment to their political aim of conserving traditional masculinity, which is being challenged by their constructed hegemony. Corporeal aesthetics and embodiment thereby become a central aesthetic mode to raw meat fanatics. Through posting the body, members of the subculture seek to transgress the anti-masculine agenda that they believe underpins ‘liberal’ (leftist) politics, deemed by them to be hegemonic. Although there is no concrete consensus regarding the hegemonic construction that exists between the influencers, nonetheless, there is some overlap. To them, the dominant political hegemony is anti-masculinity, anti-Western and advocates for ‘modernity’. According to them, these political values are embedded in the food industry, which tries to emasculate men through encouraging the consumption of seed oils and soy products, for example. They also claim that an anti-masculine ideology is causing the feminization of men, which is a consequence of, for example, LGBTQ+ ‘propaganda’ and foods that contain estrogen.

Tweet by @CarnivoreAurelius

Within the framework of this constructed hegemony, testosterone assumes an almost symbolic rather than biological status as the binary opposition to estrogen. Testosterone serves as an antidote to the anti-masculine agenda. Here, I identified one of the central logics of the subculture: Western men feel disenfranchised as a result of a supposed anti-masculinity agenda that seeks to undermine them, their masculinity is subsequently symbolized by testosterone, which, in turn, leads to them engaging in practices that increase testosterone, such as eating certain foods or going to the gym. This increase in testosterone is then perceived as a reclamation of their masculinity, which symbolically challenges the constructed hegemony; it becomes a form of direct political action. This is why the subculture is so effective: it provides guidelines for concrete practices which have an effect on the ideological plane; it valorizes food and lifestyle practices within their ideological framework. In doing so, these practices subsequently transgress the mythologized anti-masculinity hegemony: they become political praxis for members of the subculture.

Sample of corporeal aesthetics posted by several influencers

Pictures of plates (plateposting) are ubiquitous in the subculture. The correlation between (raw) meat and masculinity was not established by the subculture, though, only amplified. The consumption of meat has long been considered a masculine act, particularly red meat, which symbolizes the masculine through its bloodiness[4], most likely a vague reference to being able to hunt and kill. Red meat captures some sort of primal form of masculinity which is romanticized and striven for by reactionaries in an act of preserving hegemonic masculinity, on the contrary, not eating meat is considered emasculating[5]. The strong symbolic connection between (red) meat and masculinity is central to the subculture, albeit in a much more hyperbolic form, as it stretches the notion of meat symbolizing the masculine to its extremes, for example by eating and presenting it raw or dangerously undercooked. This aspect of the subculture’s visuality is particularly gestural and symbolic, as raw meat not only emphasizes the meat’s bloodiness, but also because it transgresses basic food-health standards. The consumption and presentation of raw meat is a gesture of commitment to masculinity in its most primal form, conjuring hunter-gatherer imaginaries. It also serves as one of the codes to signify belonging to the subculture.

The subculture’s visual practices aren’t composed solely of posting bodies and food, though; their ideology and entanglement with the alt-right becomes particularly obvious through the use of memes and alt-right vernacular. Posting Pepe or the Chad meme demonstrate their literacy of and appeal to these memetic and vernacular practices. The influencers that produce this kind of memetic content are almost always on the political side of the spectrum. They will not only post memes that are common within the alt-right, but also transform the memetic format to make it specific to the content of the subculture, such as posting pepe alongside raw meat, or the ‘Chad’ meme reading one of the influencers’ books. There is an obvious appeal to right-wing sensibilities here, as well as proficient cultural literacy in the ability to transform the memes while retaining their memetic form. The combination of both health doctrine and cultural signifiers, such as memes or certain phrases, is what makes the raw meat subculture significant among other reactionary subcultures.

Pepe the Frog with raw meat, posted by @SolBrah

‘Chad’ reading Sol Brah book, posted by @SolBrah

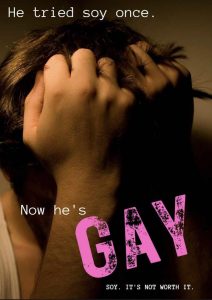

One key term that connects the overarching reactionary politics and memetic practices of the ‘manosphere’ and the alt-right to the raw meat subculture is ‘soy’ or ‘soyboy’. The interesting thing about this term is that, within the ‘manosphere’ and the alt-right, it has an almost purely symbolic value, whereas within the raw meat subculture, its usage is both literal and symbolic. The term originates from the notion that soy products contain estrogen, and thereby contribute to the so-called ‘feminization’ of men. Consequently becoming a slur to refer to emasculated or ‘weak’ men[6]. Terms like ‘soyboy’ therefore become embedded in the subculture’s vernacular practices and enforces the idea of an ‘us vs. them’, contributing to the radicalization of group members. Influencers in the subculture can further radicalize individuals through a curiosity about the scientific effects of soy products, which they argue has a biologically ‘feminizing’ effect, with the use of the term as a slur or insult subsequently having more standing. The term also relates to the conspiratorial aspects of the subculture as the food industry’s embrace of soy-based products is framed as a political act that is part of the larger anti-masculinity agenda.

The soy discourse oscillates between the use of it as a slur to screenshots of journal articles which supposedly denounce soy products. The posting of statistics, diagrams and journal articles provides supposedly concrete, scientific (and therefore axiomatic, according to the subcultural influencers) information that supports their health claims. These screenshots, most often just of the title of an article published in a journal, are almost completely decontextualized and instrumentalized to support the broader conspiratorial narratives that the influencers are pushing. The obvious irony is that they heavily cherry-pick scientific data, as there are a myriad of scientific articles arguing for the detrimental or dangerous effects of eating uncooked meat or just too much meat in general. Similarly to the conspiratorial narratives themselves, these kernels of information are decontextualized, and within their decontextualization, they are flattened into shallow symbols with reduced meaning.

“He tried soy once. Now he’s Gay. Soy. It’s not worth it.” Meme, posted by @mansworldmag_, reposted by @SolBrah

I believe the raw meat subculture, as well as parallel reactionary subcultures, emerge from the general precariousness which is the inevitable consequence of a neoliberal reality as well as a misconceived loss of political agency of Western men and attack on traditional Western masculinity. This misonception is validated by the subculture through their constructed and mythologized hegemony which heavily relies on conspiracy narratives. In New Dark Age, James Bridle describes a technological era wherein we are overwhelmed with information whilst our agency simultaneously diminishes, leading to precarity and a “sense of helplessness”[7]. This overwhelming digital reality leads to a disoriented state wherein the perceived loss of agency is mitigated through concrete, simplified, and often conspiratorial narratives, used to ground oneself. The raw meat subculture’s conspiracy narratives and attempts to regain agency through individual food and lifestyle practices are in line with the trend of reactionary, fascist groups increasingly turning to wellness and health as ideological tools in an attempt to appeal to ‘new age’ ways of thinking and being.

One of the ways in which the influencers believe masculine values are being undermined is through the food industry. According to them, industrialized food processes makes use of seed oils, processed ingredients and inorganic chemicals with the intent to emasculate and poison men. I would argue that the members of the subculture have a valid distrust in the food industry, however, their distrust and subsequent frustration is misconstrued and conflated with reactionary politics. The food industry relies on unhealthy food practices because of capitalist industrialization, not because of a political agenda seeking to destroy Western masculinity. Processed foods and seed oils are results of profit-incentives; they are cheaper to produce and grant the products a longer shelf-life among other financially beneficial attributes. This is why there are loads of scientific articles critiquing industrialized food processes and their detrimental health effects: because the food industry does produce unhealthy food. The reality of the food industry is complex, however: neoliberal industries are deterritorialized and obscured by globalized production processes and supply chains, making them extremely difficult to conceptualize in their entirety. According to Bridle, our reality is inherently complex, and becomes even more complex when we have a virtually infinite amount of data and information available to us. This is why Bridle states that the conspiracy narratives that emerge in our new dark age are:

“[…] inherently simplifications, because no one story can account for everything that’s happening; the world is too complex for simple stories. Instead of accepting this, the stories become ever more baroque and bifurcated, ever more convoluted and open-ended. Thus paranoia in an age of network excess produces a feedback loop: the failure to comprehend a complex world leads to the demand for more and more information, which only further clouds our understanding – revealing more and more complexity that must be accounted for by ever more byzantine theories of the world. More information produces not more clarity, but more confusion.”[8]

This is why the raw meat subcultures conspiracy speculation ranges from mild suspicions of the food industry to explicitly anti-semitic conspiracy narratives, using dietary and lifestyle practices as their weapons in the culture war. This instrumentalization of lifestyle practices in political projects is common in right-wing subcultures, which have subsumed new age notions of spiritualism and mysticism into their doctrine[9]. This style of spiritualism and mysticism can be traced to the 1960’s counterculture movements, which used non-Western philosophies to form the new age movement. Right-wing groups use this notion of spiritualism/mysticism in an act of rebranding and revitalizing reactionary movements. The subsumption of these ideas became particularly relevant during and after the pandemic, which was significant in the normalization of conspiracy narratives, and the re-politicization of the body in right-wing politics.

During the pandemic, speculation about government intervention as an infringement of “the sacred sovereignty of the body”[10] thrusted the corporeal onto the political stage. Right-wing and reactionary figures seized this opportunity to push an extreme libertarian agenda wherein anti-vaccine doctrine was conflated with new age ideas of wellbeing and wellness[11]. The pandemic was imperative in this shift because it repoliticized the body through the state’s intervention in individual health, which, in turn, renewed the interest in militant libertarian movements. There is an obvious connection between these ideas and the raw meat community, which argues against government imposed food regulations and a government-imposed anti-masculinity agenda which can be resisted through dietary and lifestyle practices. To these men, embodying what they believe to be ‘peak-masculinity’ is one of the most subversive gestures to an imaginary hegemony.

This is why their ideas about diet and lifestyle are often coupled with images that evoke notions of spirituality and esotericism’. These images imply that a state of enlightenment can be achieved through their lifestyle and dietary practices, that being masculine is being enlightened (i.e. escaping from the Matrix, being redpilled). Not only are these attitudes reflected by the aesthetics of the subculture, but also by the lifestyle practices and the consumption of raw meat, which become ritualistic and esoteric. Eating raw meat doesn’t have any added health benefits compared to cooked meat, at least not scientifically. This is disregarded by the subculture, which claims that raw meat is the most ‘healthy’ way to consume meat. This obviously goes beyond a scientific argument, with the raw meat instead serving the same function as other ritualized, spiritualized food practices which have no scientific foundation (I should mention that I don’t think this is bad per se, as a lot of knowledge that is derived from non-Western epistemological frameworks can be very valuable regardless of its incongruency with Western, scientific frameworks. But in the context of reactionary subcultures there is an obvious distinction).

Essentially, the consumption of large amounts of meat could actually have some health benefits, at least this is argued by some food scientists, but even scientists that propose carnivorous diets do not believe raw meat has any added benefits. Meaning that eating raw meat becomes an almost purely symbolic, gestural, and even esoteric act.

Spiritual imagery sampled from several influencers

It’s clear that the contemporary digital landscape, and the information and data flows that individuals are subjected to, have led to an increase in conspiracy narratives. Particularly within reactionary circles, wherein the complexities of a neoliberal world are (willfully) ignored, in favor of simplified, flattened narratives, coupled with a ‘return-to’ mindset. Within the raw meat subculture, the complexities of the food industry and the perceived loss of political agency of Western men are relegated to an anti-masculine and anti-Western political agenda, which have supposedly become hegemonic. Their reaction is to spread confusing information about nonexistent conspiratorial networks and hidden agendas, as well as to engage in spiritualized and esoteric dietary and lifestyle practices as a means of resistance. The construction of a mythologized hegemony that is perceived to dominate the Western (and global, moreover) political landscape is a common trend in reactionary subcultures. Nonetheless, the raw meat subculture departs from a more general reactionary subculture through its focus on diet and lifestyle, but these ‘health’ concerns are often more symbolic and gestural than scientific. The health-oriented doctrine of the subculture provides an accessible entry point to more sinister, conspiratorial narratives that are entangled with reactionary rhetoric. Influencers in the subculture instrumentalize a perceived loss of political agency and attack on traditional masculinity experienced by men, providing a political roadmap that leads to increasingly more radical and extreme views, all whilst grifting products and services to them along the way. The influencers weaponize corporeal aesthetics and photos of food in resistance to the hegemony they have constructed, supplying their rhetoric with memetic practices derived from the alt-right, as well as using decontextualized scientific articles. This is part of the overarching visual symbolism which plays a larger role in alt-right propaganda, think of the ancient Greek/Rome iconography that is commonly used to symbolize Eurocentric or Western values, for example. The consumption of raw meat is and the mythologization of masculinity is becoming increasingly pervasive in digital spaces, with an uptake of young men who follow dietary, lifestyle and political doctrine from cultural grifters who pander seductive myths to mitigate an ever-growing feeling of precarity. The concerning normalization of these reactionary, identitarian rhetorics exposes a deeply unsettling state of affairs which necessitates critical counternarratives and consistent interrogation.

Tweet by @AlpacaAurelius

–

Notes

[1] Jones, C., Trott, V., & Wright, S. (2020). Sluts and soyboys: MGTOW and the production of misogynistic online harassment. New Media & Society, 22(10), 1903-1921

[2] Rothut, S., Schulze, H., Hohner, J., & Rieger, D. (2023). Ambassadors of ideology: A conceptualization and computational investigation of far-right influencers, their networking structures, and communication practices. New Media & Society

[3] Jones, C., Trott, V., & Wright, S. (2020). Sluts and soyboys: MGTOW and the production of misogynistic online harassment. New Media & Society, 22(10), 1903-1921

[4] Nath, Jemál. “Gendered fare?” Journal of Sociology, vol. 47, no. 3, 27 Jan. 2011, pp. 261–278

[5] Nath, Jemál. “Gendered fare?” Journal of Sociology, vol. 47, no. 3, 27 Jan. 2011, pp. 261–278

[6] Jones, C., Trott, V., & Wright, S. (2020). Sluts and soyboys: MGTOW and the production of misogynistic online harassment. New Media & Society, 22(10)

[7] Bridle, James. New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future. Verso, 2023.

[8] Bridle, James. New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future. Verso, 2023.

[9] Peters, Michael A. “New age spiritualism, mysticism, and far-right conspiracy.” Educational Philosophy and Theory, vol. 55, no. 14, 20 Apr. 2022, pp. 1608–1616.

[10] Tuters, Marc. “The conspiritualist.” The Journal of Media Art Study and Theory, vol. 4, no. 1, 25 Apr. 2021

[11] Peters, Michael A. “New age spiritualism, mysticism, and far-right conspiracy.” Educational Philosophy and Theory, vol. 55, no. 14, 20 Apr. 2022, pp. 1608–1616.