By now, everyone knows that the normally smooth functioning world of information and communication is not to be trusted or taken for granted. Designers and researchers devise methods, protocols, checks and regulations to somehow ward off the inherent possibility of technology-enhanced evil. An entire industry of design ethics and (digital) security has emerged that not only tries to eliminate malicious intrusions and hacks but also considers, for example, the necessary resources, energy consumption, or complex distribution channels involved.

In September 2024 thousands of personal devices exploded in Lebanon. A horrifying chaos suddenly irrupted throughout the city, impacting anyone around at that time. To have such devices explode just when receiving an incoming message, on this scale and with this sophistication, was unprecedented. As research into Pegasus spyware has shown, it can’t be considered an isolated event. Finding vulnerabilities in our advanced technologies is actively invested in by specific powerful companies, like the NSO Group, to be used against a wide range of individuals and organisations. We can only guess what possible evil schemes are still lurking in the complex technological systems we use daily.

Everyone involved in complex technologies, whether as researcher, artist, designer, or even anyone working on newest innovations in the industry, should be concerned. There seems to be a lack of convincing strategies to engage with such evil, whether it is malicious attacks, unexpected effects of climate collapse, or anything else that might catch us off guard. How to come to terms with all possible evil? Baudrillard’s remarkable book The intelligence of evil, or the lucidity pact offers an altogether astonishing radical approach, when we skip his outdated examples and abstract musings. Evil, according to Baudrillard, always involves some ungraspable strangeness and disruptiveness that cannot be totally predicted or understood in its devastating consequences. It will always seem to have outsmarted all precautions and preparations, and this is what makes evil intelligent. But throughout Baudrillard’s writing, this intelligence of evil is at the same time something promising. It might offer a starting point for anyone interested in more incisive critical inquiry and creative exploration. By closely revisiting his writing below, we chart a decisive path for creative investigation and resistance in the face of the evil that resides in the pervasive technologies that surround us.

The Evil of Gen AI

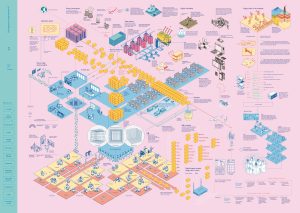

Current generative AI, hyped and implemented in different domains, is already quite evil in itself. We don’t need to delve into the technical details to note that it produces an incessant succession of non-committal output. The existing critical academic discourse around generative AI and its inherent problems, nicely visualized (picture), gets overshadowed by the drive for new commercial opportunities and investments. It can be used for personal diversions, but it is mainly applied for modernizing instant payment systems, for making medical decisions in healthcare, or, for example, for freight brokers automating their operations.

Corporations such as Unilever, Ikea, Pfizer, KLM want to take the lead in the abstract process of ‘integrating’, ‘optimizing’, and ‘implementing’ these systems – as the AI Expo program of this month shows. These generative AI systems are being distilled into our entire technological machinery based on their supposed utility and pleasurable efficiency, but, as Baudrillard warned more generally and aside from the already acute inherent problems, are fostering a general equivalence, indifference, banality. The images and texts created lack any distance and further critical or aesthetic gaze and, as recently argued, are likely to be reprocessed more and more to the point of overall downgrade and degradation.

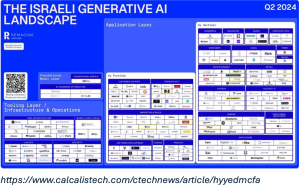

In Israel, a surge of generative AI startups (picture) is paralleled with the rapid advancement of new military technologies. In addition to the intrusion and spyware mentioned above, this is also where the latest intelligent systems like Gospel, Lavender, Iron Fist, Mabat 2000, the Basel System, or Blue Wolf are developed. These systems generate possible targets, proposals for assassinations, and generally routinize violent action and effective destruction. When all is destroyed, the focus of these systems and technologies can easily shift to restoring, only falling back into what Rob Nixon termed slow forms of violence, continuing to exacerbate the vulnerability of the ecosystems of the disempowered and involuntarily displaced people, for example by further decimating fertile land and realizing strict forms of surveillance. Baudrillard noted the irony of anti-terrorist systems ending up creating terror – even when they are presented as counter-terror. Indeed, it is what David Graeber summarized in his reflections from a visit to the West Bank as a hostile intelligence operating through violent and calculated form of terror, and again, degradation.

To the degrading banality and indifference of automatically generated content is added the degrading routinized violence and terror. Baudrillard already described this degrading dynamic, although he did not know the precise technologies would be developed, how these are also degrading ecosystems and all kinds of non-human lifeforms, nor the concrete financial incentives, policies or the political climate that supports it all. Still, Baudrillard he noticed a tyranny of the so called user-friendly and interactive spectacle, which he thought was threatening us on all sides. He thought it could amount to destruction and annihilation of meaning, of history, and of all political substance in the void of news and fragmentary information. It seems to be in line with what Maya Wind has observed in Israeli universities, pointing out the meticulous communication and research output, which hides the de-realization of specific histories, contribution to settlement expansion and land claims, and the overall promotion of the security state from view, and at the same time making collective action or resistance almost impossible. Israel seems to be the current best example of programming power that in terms of software and information is almost total and, as Baudrillard expected, at the height of its mastery only seems to be able to lose face.

All in all, it fuels current anger and frustration in student protests around the world. Universities that keep collaborating do not want to admit and account for the complicity in what these protesters think is indeed some terrible evil. By revisiting Baudrillard’s work, however, a broader and more profound conception of this evil emerges, and in addition, creative resistance would not have to revolve so much around barricades and occupations but could take a more complex and multifaceted turn.

Stupidity Overload

What the tyranny of artificial intelligence leads to most surely, Baudrillard wrote, is the birth of a previously unknown stupidity – artificial stupidity – deployed everywhere on the screens and in the computer networks. What he pointed at shouldn’t be mistaken for the artificial unintelligence that Meredith Broussard wrote about, which resides in specific design choices, a lack of diversity in tech companies, and more general in some technological chauvinism. Instead, what Baudrillard was concerned about is a stupidity that, as Tom Grimwood describes, more fundamentally affects all kinds of interpretative relationships. Grimwood elaborates how stupidity nowadays dwells in difficult to influence prejudices, in a specific kind of archiving and active curating of information, a heightened economy of suspicion and a general expectation of error, all of which is maintained through online chatter and banal habitual repetitions. He notes how this all makes current stupidity very hard to navigate. What makes this navigation even more complicated is that this stupidity is reinforced, as David Graeber describes in The Utopia of Rules, by a self-perpetuating web of financialization, violence, and technological development. Achille Mbembe further emphasized the racism involved in this stupidity and the violence it causes, which, according to him, indeed defines the very spirit of our time. Taken together, the artificial stupidity that Baudrillard saw emerging through all kinds of technological systems, seems to be substantiated in more recent theories as something that defines and fundamentally complicates our current age of technologically mediated evil.

Researchers, artists and critical designers who want to anticipate possible negative consequences of new technologies have already devised various tricks to try to stay away from this stupidity. To this end, new well-intentioned research approaches, methods, critical concepts are being developed. Every project or event is supplemented by an additional justification, a critical compendium, an ethical review, or a list of further improvements. This is how any unwanted habits, prejudices, and more general potentially problematic interpretative relationships are navigated. But there is a trap in taking everything apart to try to criticize, justify or improve it. Any act, any event, any detail of the world, Baudrillard claimed, can be considered good or might at least become beneficial, provided it is escribed, isolated, taken apart. Almost anything can be approached that way, as last IDXA, a mayor event for interaction designers, showed.

The program combined separate talks on regenerative AI and abundant intelligence, on corporate approaches to climate action and better intelligent policing, while also discussing the prevention of burnouts within the field – again and again offering clear examples, positive and seemingly beneficial aspects, clever analyses, but without stating the mutual contradictions and the fundamental impossibility of combining it all. It becomes an almost automatic and irresistible mechanism, to the point of constituting, in what Baudrillard described in more general, a hegemony of good, that now even Group or the military industrial complex will be happy to participate in and contribute too. Baudrillard surely would have opposed such professional but tricky and naïve navigating of stupidity in the face of evil.

The more we acknowledge the evil that resides in current technologies and understand the complicating stupidity that it instigates, the more we seem to get locked into a discouraging impasse of critique. The actual evil cannot be combated, certainly not frontally, the stupidity cannot easily be outsmarted, and degradation cannot simply be turned into something good or promising. The problem is also, according to Baudrillard, that there is already too much of it, as we might now say that there is too much data, too many perspectives to take into account, too much ethical guidelines and possible concerns. Further regulations meant nothing, as he noted a surfeit of politics which drives us out of politics to ever more privilege, vice and corruption, including the corruption of ideas. Self-criticism was for Baudrillard just another mode of governance that is constantly holding up new mirrors. Standing up for human rights or social justice gives, he thought, is unable to radically end all injustice. It all turns into an endless exercise of further critiques that will just be further capitalized on and defused. Baudrillard would see all of this as part of a mental involution towards a zero degree of thought, which may very well include what we would now call capitalist realism, cruel optimism, or elite capture. That is why Baudrillard proposed a different way of thinking and another creative perspective, because after all, we cannot simply let evil and artificial stupidity continue.

A Lucid View of Evil

At this point, it is easy to expect Baudrillard to lapse into some kind of nostalgia or nihilism (and some think hid did). But there is no need to be pessimistic, he insisted. If we follow closely his thought on intelligence and evil, it is possible to take from it a surprisingly radical and inciting creative stance. If it is the whole world that must be taken en bloc, he writes, then it is at that point we reject it en bloc. A rejection similar to the biological rejection of a foreign body.

Such a rejection can indeed also be taken as a fresh starting point, as the recent call for artists and activists articulated for a gathering at TITiPI to critically investigate NVIDIA, whose chips are used for gaming, telecom, scientific research, aviation and logistics, as well as for use by military companies like Lockheed Martin and Elbit. They aimed to “articulate interdependencies between global financing, AI, hardware development, and computer graphics” including “how these industries are complicit in extreme violence”. The plan was to “use all means necessary to figure out ways to contest, resist and undo some or all of these systems”. It is reminiscent of the kind of action that was also taken against Google, which is participating in project Nimbus, project Maven, but also known for all kinds of privacy violations, mass surveillance, and complicity in gentrification. Initiatives like Fuck off Google rally people and share all kinds of dissenting and protest, and are supplemented by all kinds of creative inquiry and defiant exploration as F.A.T.’s Fuck Google Week at Transmediale 2010 explored and also Miss Data’s Schmoogle shows. Yet such creative research and action aimed at leading companies, however interesting, can also feel inadequate in relation to the actual pervasive evil that continues to proliferate. These interdependencies we may be able to articulate and challenge, but ultimately we have no say in them and can hardly stop, let alone undo, our complicity.

Evil actually comes to pass in exactly these interdependencies, in a complex ecosystem of decisions, cascades of influences, multifaced social factors, as Julia Shaw demonstrates through multiple examples. Evil is not simply a malign force, a maleficent agency, a deliberate perversion or disruption of the order of the world: it is something more ungraspable and incalculable. Deliberately practicing evil lacks insight into evil, Baudrillard wrote, mistaking it for something intentional. This is a pathological inversion, as we now see personalized in supervillains like the Joker, or in other forms in the movies and popular art that Warwick describes. Baudrillard maintained that there is actually no person, no group, no behaviour, no natural phenomenon that we can target and dismiss as evil. It is not just the Israeli forces planning the attack, nor a particular intrusion, just as it not just comes to light in an actual observable climate collapse or in some future nuclear war. The evil is already latent in the existing data, in the bulk of applications, in the industry of high-tech devices, in the working conditions, in the interactions and social relations that are constituted, in the algorithms that make it all function. This is what he called a lucid view of evil. Evil is present everywhere in homeopathic doses in the abstract patterns of technology, wrote Baudrillard, always intelligently finding different ways to reverse, invert, crumble and overturn the dominant order and reality we live.

By putting it this way, perhaps this intelligence of evil has something to offer for an overall rejection of the degradation, terror and stupidity. Perhaps we need exactly some evil intelligence to finally have the current degrading systems overthrown. Taking the side of evil might be a final way to indeed reject the world en bloc. For some this might seem a very provocative stance but remember that this evil is not to be mistaken for terror, violence or malice. Not at all. Evil is to be found in all kinds of suicidal crumbling, reversion, interruptions and outgrowth of technologies that are already there and that we hardly seem to notice. It is almost as if every system, alongside the ingredients of its power, secretly nourished an evil spirit that would ensure that these same systems are being overturned. To see this almost secret potential of evil, we must not reduce these reversals and crumbling to mere bugs, as problems to be solved, nor as an opening for hostile abuse to be prevented, neutralized or re-appropriated. Evil then is not something we can or want to impose our will on or, for that matter, simply embrace. The only thing we can do is somehow come to an understanding with it, and this is exactly what Baudrillard suggested.

To become aware of them we have to pass through the non-event of news coverage to detect what resists that coverage. We must turn against the machinery of commentary and journalism that neutralizes all potential. This seems in line with creative practitioners and researchers such as Joler and Crawford who take a more investigative approach to technologies beyond the latest gadgets and fun features, for example critically visualizing complementary histories or the necessary labour, industries, logistics, and optimization behind it all. But there is one final creative step Baudrillard invites us to take, because this is certainly not yet the actual rejection he was looking for. He would have thought it necessary to further play out the interesting evil possibilities and turn them into a drama, but not in order to sublimate or resolve them in any way.

Play by Our Own Rules

To identify all different the possibilities that evil has to offer, we might need a further unruly practical wisdom regarding the systemic ambiguity, leaks, exceptions, errors, that Goffrey and Fuller discuss in their book Evil Media. We might want to study exploits and spam-bots, viruses and hacks, and the “uncomputable” that Alexander R. Galloway has explored over the years. As Galloway also seems to suggest, this is not just about examining games, for example, but trying to expert with them to see how they can go against the “rules of the game” that these NVIDIA chips, Google’s cloud services and all sorts of systems impose on us. We will not be able to outsmart the rules of the game, we will not master them, nor should we want to. The only thing we can rely on in the end, is some kind of reflex of no longer wanting to play this game at all, to reject the overall rules of the game. Which does not mean we will completely quit. The way to do this is to make up a totally different set of rules to play by in whatever we do.

This, then, will not be just another design exercise or art project, it is not just another research topic or academic discussion, nor some kind of personal duty or individual challenge. We need to organize ourselves otherwise and create all kinds of militant forms of action in the face of tech evil, to bring this evil to the fore, through what Baudrillard suggested had to be a pact of intelligence and lucidity. We have to experiment with all kinds of self-defined and evil-minded rules to play by in all the work that we do, in the use of all kinds everyday systems, in the programs we participate in, the protests we engage in, the networks we will be part of, and the institutes we deal with.

If the stakes are high, Baudrillard suggests, such new initiatory set of severe rules should condense all the dimensions of the game into one. These dimensions, which Baudrillard borrows from Roger Caillios, can be translated as dependence on physical training, mimicry, luck, and the search for vertigo. In other words, our further (creative) endeavours – the designs, texts, objects, architectures, infrastructures, protests, crimes, events, research projects, performances, or whatever we are inclined to engage ourselves with – should always directly pose a challenge, bring chance into play, produce vertigo, and at the same time become an allegory for other new instances. To play by such rules, we will also have to stay close to the fundamental strangeness and irrationality of ourselves. We will have to resist the status of subject with a clearly defined profile or identity. It is not about becoming a more radical game designer, a more engaged artist, a more radical researcher, a more intelligent activist or hacker. The only chance is to have no predefined end goal, no ideal formula, and no alternative solution, Baudrillard insisted. We just have to keep up navigating the stupidity, to come to terms with the evil of the latest technological developments, and reject the current degradation and terror, through our own defined imitative, challenging, dizzying, gambling rules for creative action and further critical research. This is what Baudrillard has given us in the last pages of his book.

From here on, we need to leave Baudrillard behind. After all, he wrote this book over 20 years ago and the technological developments continue to evolve rapidly (in his book he references typewriters, then-current trends in photography, Minority Report and 9/11). Here it becomes necessary for more contemporary thought to guide our way. Like, for example, the attention for disobedience in digital societies (Quadflieg et al.), algorithmic sabotage (ASRG), or algorithms of resistance (Bonnini & Treré) which can be further practiced and developed to find openings to more possibilities for the evil overturning of degrading technologies. So, instead of redesigning and reorienting the “eye of the master” like Matteo Pasquinelli discusses at length, it is about distorting the masters eye, by exploring what is already somehow clouding or obfuscating its vision or troubling it in general, and also what is distorting our own vision of even more fundamental disturbances. Better understanding the cases of, for example, etoy or maybe the stories from Fancy bear goes fishing can help us better navigate artificial stupidity in its full social complexity and make us better understand how technological expertise, engaging with popular culture, but also lawsuits, funny coincidences, creative discoveries and philosophical thinking might be necessary.

We can be inspired by the research of Lisa Blackman who uncovered broader relational errors, dead ends, ghostly figures and misunderstandings that indeed still haunt our systems. It amounts to something what Caroline Bassett calls anti-computing, which is surely no refusal of computing as such, but an altogether different affective taxonomy, media archaeology, and commitment to radical structural politics which ‘persists across the decades of computational instantiation in recognizable forms, even as it also shifts, morphs, finds new targets, or reshapes older ones’. This, then, is what our complicity with the intelligence of evil can further reiterate and revitalize. This is the decisive path for creative exploration and resistance that Baudrillard has somehow already carved out in relation to the evil that lurks in the ubiquitous technologies that surround us, which is up to us to further explore.

—

Eke Rebergen teaches at the Communication Media Design school of the Avans University of Applied Sciences in Den Bosch, the Netherlands and is a PhD candidate at ASCA, University of Amsterdam.