Жить тяжело и неуютно

Зато уютно умирать

(Living is difficult and confining,

But dying is liberating)

The words written above are an excerpt from the song Sudno (Boris Ryzhy) by post-punk band Molchat Doma from Minsk. These words also often loop over the reels on post-Soviet aesthetics found online – the ones of decayed brutalist buildings with blue and grey undertones, or snow-covered, rectangular residential blocks with crumbling soviet elevators. Such content online grabs me instantly because of its familiarity, but it also grabs me because of how it claims the space. I am drawn to it insofar as I’ve been part of that infrastructure, but I am also consciously keeping the distance because it feels too close, too empty, and too sticky.

Some objects or bodies are ‘stickier’ than others, forming a relationality, or “withness”, where things that are “with” each other get bound together. Sara Ahmed uses the analogy of stickiness to reflect on how disgust can generate effects by “binding” signs to bodies, as a binding that blocks new meanings. In digital culture, I see this as one form of an affective shift to online spaces – how some objects, more than others become sticky on the Internet, and how they accumulate layers of meaning through repetition and circulation. These objects or ways of understanding a certain lifeworld sometimes become territorial; they bind to some bodies, desires and affects, sticking in ways that close off other forms of engagement. What interests me is that the more they firm their presence online, the more they seem to pull our emotionality in, until the point when our encounters with them become habitual.

With this in mind, I want to engage with Soviet and post-Soviet aesthetics on the Internet. Yet, it feels impossible to deconstruct the presence of online remains of the Soviet/post-Soviet world without becoming entangled in its own memetic landscape, and ultimately becoming part of it. The very act of reflexivity I use while scrolling through Instagram and TikTok pages dedicated to post-Soviet lifeworlds—blurs the line between observer and subject—I critique but I also consume. So, in a way, this article becomes its own kind of meme. I find myself stuck as a meme insofar as I am absorbed by it. For the more serious the analysis becomes, the more it echoes the same meme narrative post-Soviet aesthetics on the Internet continuously produces.

The stickiness, when touching upon the post-Soviet meme world, holds a quality of fixedness. It is firm and unmovable. Whatever sticks to this certain aesthetics found on the Internet is frozen and fixed in time – it cannot be removed as its digital footprint will be elsewhere. Yet it continues to shift within its own limits, as it is also stuck with its own boundaries, trapped between forming and erasing meanings, old and new. This leads me to the space between these acts of fixation and circulation—the space between sticking and moving. How, then, is the “post-Soviet” performed on the internet?

Ownership of post-Soviet memorabilia on the Internet, and liminality that comes with it

The term post-Soviet does not just refer to the aftermath of the collapse of Soviet Union, but sets the two in a reciprocal relation, where what is considered Soviet is a construct of the post-Soviet present. Multiple Instagram/TikTok pages soak this up. While producing Soviet narratives for various purposes—educational, nostalgic, or entertaining—the imageries of post-Soviet lifeworld are continuously accumulated, reconstructed, and reimagined. What my Instagram algorithm provides is ranging from austere appearance of Soviet propaganda posters, or the captions of pages like soviet-movies: “Subscribe, Tovarish[1]!” – and easternblocgirl – “dropping some Eastern European vibes on the Internet” with the weekly reminder, “going insane in Eastern Europe Wednesday”, to Soviet_busstops, giving surprisingly detailed descriptions of bus stops found in post-Soviet countries.

What I see, is that this specific content on the Internet is multi-layered and in a constant flux, but more impressively, it has its own digital infrastructure.

Figure 1: Louvre in Russian (Last viewed on October 22, 2024)

Take, for instance, the Instagram page easternblocgirl, where the aesthetics of post-Soviet life are curated through images of scraped-off light blue walls, crumbling brutalist buildings, and the gritty surfaces of “Sovietcore.” “I can smell that подъезд[2] through the phone”, comments one user on the photo above. And I can smell it too. Being born and raised in a post-Soviet country, this picture resonates with me deeply, for I also have been living in “one of those” Soviet brutalist buildings. It reeks of old dust that stings nostrils, of damp walls, beer, and indelible marks of cigarette butts, the texture of the light blue wall, which is similar to how school classrooms were painted in the early 2000s. It is not only simply a building but a sensorial memory that clings to me and other bodies shaped by this very infrastructure.

These are archives of feelings, of that stickiness. And there is a subtle dimension of the social: sensory landscapes we become endowed with, treat us as active record-keepers, used as an extension of human memory with continuing value. In this instance, we seem to be value carriers, while the sensory modalities affect our lived experiences and make our bodies become witnesses of the material experiences. Yet, the Internet is fragile in this regard, as these experiences are flattened into digital archives, fragmented and reduced to visual traces on screen. One cannot locate the digital manifestation of a Soviet past residue in its own socio-political context.

The easternblocgirl Instagram account is marked by its own disembodiment. The sensory connections it evokes, might be more about collective imagery or invented nostalgia, rather than a personal memory. This uncertainty complicates the relationship between digital archives and lived experience. Instead of asking where these memories truly belong and who gets to claim ownership, I would rather question how we become the owners of post-Soviet memorabilia as we perform on the very remembrance that has a fictive, invented quality to it.

Paul Connerton argued that performativity cannot be thought of without a concept of habit; and habit cannot be thought of without a notion of bodily practices[3]. Bodily practice can be reached through virtual interactions in case of easternblocgirl. If we use our virtual bodies to perform on post-Soviet memories, we are doing so in a manner of thinking and feeling through the infrastructures. Infrastructures do fix space and time when being built, but they are not hard to reverse. As things in motion, they fall into decay and deterioration, and also, they repurpose themselves over time. Mentioning time here as a temporal dimension is important for several reasons. I oppose Akhil Gupta’s argument when examining infrastructure as an entry point into future desires, aspirations, and one’s life trajectories. He writes that often, infrastructures are shaped by notions of futurity, which then in turn moves the discussion to what they signify for future[4]. Limiting thinking about infrastructure in terms of its futuristic desires risks detracting from the narrative of its multidimensionality. For when delving into post-Soviet infrastructures displayed online, the space for futuristic aspirations lacks its purpose. Users do not seem to look at this matter in a way that would position decayed buildings as desirable places to live.

Instead of futuristic narratives, these types of infrastructures associated with post-Soviet aesthetics on the Internet create the kind of temporality that does not orient itself towards future, but towards the liminality – the disorientated state of being between what is no longer there, and what is not there yet. In other words, it is a temporal sense of nostalgia towards the past that drives such aesthetics. And more importantly, this nostalgia might be invented the way the past is reinvented, reconfigured and affective.

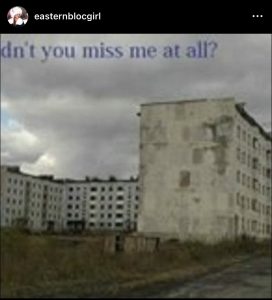

Figure 2: Beautiful New World in Russian. (Last viewed on October 22, 2024)

Figure 3 (Last viewed on October 22, 2024)

Reality Bruised

Infrastructure can be defined as the assemblage of people, objects, practices, and institutions that enable and sustain these patterns, or more concisely, a “matter that moves matter”[5]. Pages like easternblocgirl are not just visual archives—they are dynamic, ever-flowing spaces that act as affective infrastructures, carrying the weight of the past forward. We come, then to what is perhaps a re-emergence of Soviet past residue in its new forms. These new forms are not merely of nostalgic quality, they are also tied to an affective infrastructure.

Just as some infrastructure projects in the Soviet Union were a way to insert state power over territories, people, and the environment, so too the post-Soviet aesthetic found on the Internet transforms this narrative, vacates the state-led power and repurposes these infrastructures. There is a discourse under the umbrella of post-Soviet aesthetics that has installed itself as a place re-invented. Cloaked in dull and grey brutalist, decayed buildings, and hyping itself as Slavic “core” having a quality of suffering – the one that elicits nostalgia, melancholy and loss. These transformations in digital culture are not only a visual shift but also an affective one. In this way, this certain understanding of the past and present crumbling post-Soviet infrastructure could be seen as a source for an emotional landscape that offers new narratives of belonging and desire.

Figure 4: (Last viewed on October 22, 2024)

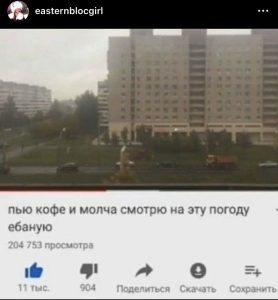

Figure 5: I drink coffee and silently gaze at this fucking city in Russian. (Last viewed on October 22, 2024)

These Instagram posts of decayed buildings and low-resolution images create a sense of dislocation, an almost Burroughsian “junk time”—a time that is both past and present, liminal, real and imagined. When looking at these pics, I am tempted not only to contemplate the object in mise en scène, but also ponder the object that captured them, which, in my own remembrance would be Samsung’s or either Nokia’s old flip phones. Seeing the present visual culture in its own capitalist hierarchy, it becomes clear that the contemporary image system has a tendency to establish a hierarchy of images, based on their “quality”. In this regard, high-resolution pictures become an attractive and immersive economic force, whereas low-quality images are further marginalised and represent technological failure. Yet, in this instance, low-quality runs the monopoly over the content, which further helps to glorify the context – it becomes an integral part of the aesthetic itself. The very visibility of technological and infrastructural failure, and the detachment from an overly polished discourse of images online, absorb the post-Soviet imagery in a way that it becomes intimate.

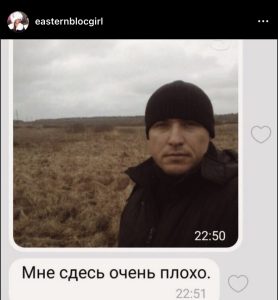

The space praises itself as seductive, luring the viewer in by temptingly asking whether one misses it, embodying a sentiment of innocence and affective properties that generate a narrative and active construct. The online post-Soviet performance almost created an alternative, “bruised” realm of orientation, a space that is being claimed as inherently glitched, ripped apart, and worn out. I suggest that such orientation in motion acts as a repository of feelings and emotions, creating an accidental memory community. “I feel very sick here”, says the meme (Figure 6). Under the same meme found on vk.com, another user comments, “I feel sick here too”. Feeling sickened is always directed toward the object, as it is the very object that makes us feel repelled. This also implies the spatial quality of such an object, which, in this case, can be the dislocated post-Soviet space itself – a digital site that saturates certain emotionality in a shared experience.

Figure 6: I feel sick here in Russian. (Last viewed on October 22, 2024)

Figure 7 (Last viewed on October 22, 2024)

Figure 8 (Last viewed on October 22, 2024)

There is a shared sense of “missing something”; however, it is an accidental longing, as there is no implicit or explicit shared purpose, or a unified narrative where community members practice a specific type of remembrance or have a specific goal to reach – the constitution of the community occurs by accident. I suggest that these types of places create an online interaction where users can pass through or sometimes even settle in such material networks without actually belonging there. I treat such users as accidental members of memory community, and memory precisely because it is oriented towards the past in a liminal way. Together with accidental, reinvented remembrance practices, the emotionality and relatedness – real or imagined – that these memes or comments bring forth further reinforce the idea of reconfiguring affective infrastructure. We think and feel through infrastructure that is affective as long as we embody such online presence as something tangible and experiential.

—

References

Ahmed, Sara. 2014. The Cultural Politics of Emotion, Edinburgh University Press.

Connerton, Paul. 1989. How Societies Remember. Cambridge University Press.

Gupta, Akhil. 2018. “The future in ruins: Thoughts on the temporality of infrastructure.” In The promise of infrastructure, edited by Nikhil Anand, Akhil Gupta, and Hannah Appel, 62–79. Duke University Press.

Larkin, Brian. 2013. The politics and poetics of infrastructure. Annual Review of Anthropology, 42:327-43

[1] A comrade in Russian.

[2] Building entrance in Russian.

[3] Connerton, Paul. How Societies Remember, (Cambridge University Press, 1989), 6

[4] Akhil Gupta,”The future in ruins: Thoughts on the temporality of infrastructure”, in The promise of infrastructure, ed. Nikhil Anand, Akhil Gulta, and Hannah Appel. (Duke University Press, 2018), 63.

[5] Brian Larkin. “The politics and poetics of infrastructure” Annual Review of Anthropology, no. 42 (2013): 238