Video games, as interactive forms, create a space where participants not only consume content, but also create, shaping virtual lives and narratives in real time[1]. At 8 years old, The Sims 2 introduced me to a quirky, engaging world that became my first exposure to life simulation. I didn’t think much about their significance growing up—I was just obsessed with playing. However, in this space, I was an active creator; it became a tool I began to understand, with its codes and mechanisms. The Sims 2 I encountered which had some strange, now in The Sims 4 removed, elements like burglars (who would sneak into your house accompanied by music that could trigger a heart attack), gloomy social workers taking kids to the Orphanage, the Wohoo cutscene (that made you glance over your shoulder, hoping no one would walk in and catch you), a literal mental breakdown (with a Social Bunny falling from the sky and a hypnotizing Therapist), and maids dressed in stereotypical and, let’s face it, sexist outfits. And of course, male Sims being abducted by aliens and mysteriously impregnated (I don’t even know how to comment on that).

Look at how saucy this early The Sims 2 trailer is…

byu/Maulclaw inthesims

Source: https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/life_simulation

I am not sure if this is how I would describe deleting the pool ladder and drowning one Sim after another, just to create a massive, impressive cemetery. Or, if you’re feeling more ambitious, trapping them inside walls with only a grill, forcing them to cook until they burn. It’s not just about the act of causing chaos but also about pushing the game’s systems to their limits. The Sims offers a playground where morality takes a backseat to experimentation, allowing players to explore the boundaries of control, agency, and the consequences of their choices.

Source: https://sims.fandom.com/wiki/Game_guide:Killing_Sims

The Sims is a life simulation video game series created by Maxis and published by Electronic Arts. With nearly 200 million copies sold globally, it ranks among the best-selling video game franchises ever. The Sims series began with the release of its first game on January 31, 2000, followed by The Sims 2 on September 4, 2004, The Sims 3 on June 2, 2009, and The Sims 4 on September 2, 2014. In September 2024, EA announced there would be no The Sims 5 but that The Sims 4 would continue to evolve.

The Sims Logos

As part of The Sims 2 generation, I found myself particularly intrigued by the life of Don Lothario, the notorious heartbreaker. I was fascinated with how his four simultaneous affairs played out and, more importantly, how to keep his secrets from being uncovered. In his company, I discovered the mechanics of The Sims, where the game is equipped with both a build/create mode and a life mode. Our Sim is categorized according to Life Stages, Traits, Aspirations, Careers, Skills, and Lifetime Wishes. In gameplay mode, you can develop your Sim across all these categories, as well as build Social Relationships and manage their needs through Interactions.

Ian Bogost’s assertion that video games act as rhetorical devices—tools for exploring complex systems through interactive simplification[2]—offers a profound lens for understanding The Sims which distills human life into manageable, gamified components. These mechanisms were developed in the creation of the real-life simulation, effectively creating an alternative version of perceiving life by categorizing and creating a visual representation of phenomena that are normally invisible and intangible. Through this process, a new way of perceiving the world was formed, one that transcended the boundaries of the game and became a language of communication. The digital world of life simulators, originally modeled after real life, now loop back to influence it, blurring the boundaries between the two realms.

Source: https://x.com/CaraLisette/status/1822689385051295845

Simification of The Human

The mechanics of The Sims have evolved into a language through which people communicate not only about the game itself but also about their own lives and the world around them. These mechanics have found their way into memes, become the subject of online discussion, and are frequently referenced in everyday conversations. What makes these mechanics so compelling is their ability to distill complex human experiences into simple, visual, and interactive systems. Concepts like fulfilling needs, managing aspirations, or building relationships are compelling because they parallel the invisible frameworks that shape real life.

Needs

One of the most iconic mechanics in The Sims is the Needs system, which is split into eight core categories—Bladder, Hunger, Energy, Fun, Social, Comfort, Environment, and Hygiene. These must be maintained for well-being and are represented as bars that gamify basic human needs. Green signifies balance, yellow indicates decline, orange signals urgency, and red warns of a critical state that could lead to collapse or even death.

By translating normally invisible human experiences into visible cues, the system allows to show abstract concepts like mood and deterioration in a tangible way. While it may be a simplification of real-life complexity, it has proven to be an effective and relatable tool for communication. The Needs panel resonates so deeply that people often use it as a metaphor to describe their own states, adopting its straightforward framework to express emotions, struggles, and personal challenges in a way that feels universally understood. As Sherry Turkle suggests, we become the simulacrum of our own lives. The boundary between real and virtual is increasingly indistinct, as we model our lives in simulations and then live them out in simulations[4]. This observation highlights how The Sims mechanism allows to model and perform aspects of life through the game’s mechanics.

Is this why therapy is so expensive?

byu/comedygold24 inthesims

In video loop MOOD (2021), I incorporated both the Needs panel and the Plumbob—the hovering crystal that not only indicates a Sim’s mood but also signals their status under the player’s control. By drawing on the game’s familiar visuals, I reinterpreted its mechanics as a language to express complex internal states. In the raw, spontaneous nature of the work—recorded with a mobile phone in a computer lab—I reflected a profound sense of helplessness and an inability to articulate an emotional state using borrowed symbols to convey feelings that otherwise felt inaccessible.

By weaving The Sims 2 soundtrack into the piece, I drew on another iconic motif that many would recognize instantly. The familiar music not only evokes nostalgia but also grounds the work emotionally, contrasting the playful tones with the underlying themes of exhaustion and vulnerability. The music serves as a shared cultural reference that further connects the piece to the collective experience of those who have spent time in the world of The Sims.

This is encapsulated in the title MOOD, a short phrase that can carry multiple meanings yet, in each instance, feels remarkably precise and clear. Whether referring to emotional states, personal energy, or even fleeting moments of being, mood resonates as a succinct and universally understood expression. It’s a term that transcends specific contexts, becoming a representation of individual experiences that are simultaneously shared by many.

In this context, the self-image I present through my work, using The Sims mechanics, becomes a tool for exploration, while also acknowledging the broader social and technological frameworks that influence how we understand ourselves. Rather than focusing on the self as a fixed entity, MOOD highlights its fluidity, shaped by both internal experiences and external systems.

Traits and Interactions

In The Sims, interactions are the core actions Sims perform with other Sims, objects, and their environment, forming the foundation of gameplay. These interactions govern communication, relationships, and engagement with the world. Some are simple, like eating or watching TV, while others are more complex, such as building friendships, falling in love, or starting conflicts. Sims can also engage in self-directed actions, like practicing skills, reflecting on emotions, or fulfilling their own needs. The way Sims interact is shaped by their traits—key aspects of their personality that influence their behavior, preferences, and reactions to various situations. Traits determine how Sims respond to others and their environment, ultimately guiding the course of their lives.

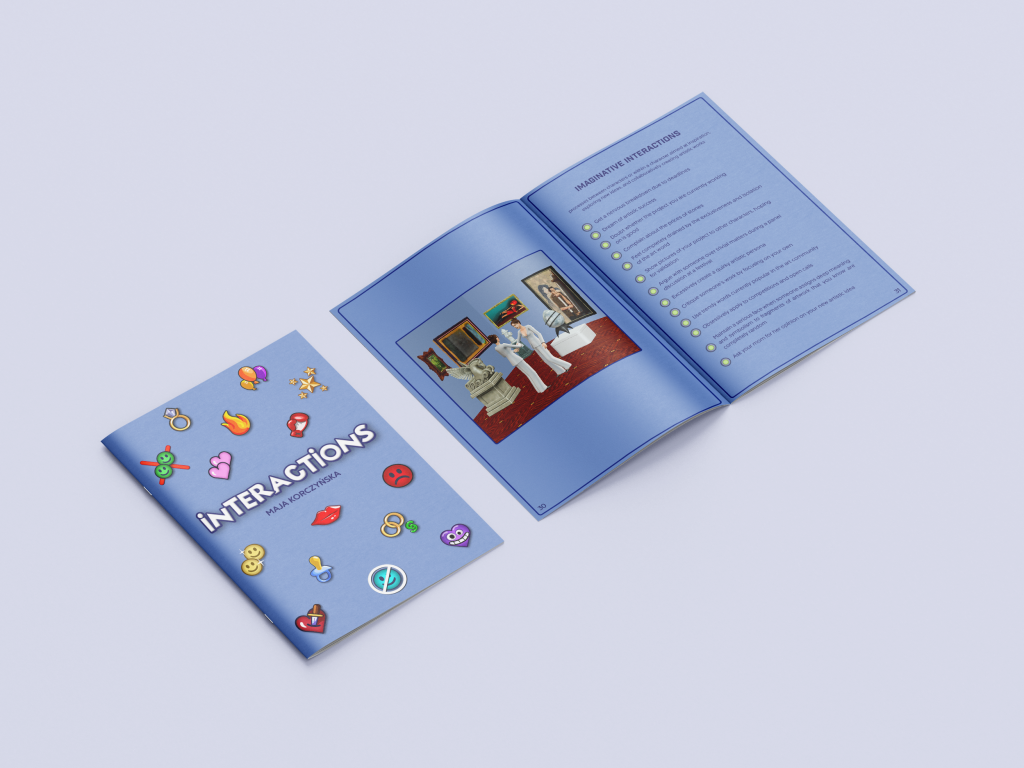

INTERACTIONS (2023) is a 12×17 cm publication inspired by the instructional manuals often included in DVD video game packaging. Printed on slightly glossy, newsprint-style paper, it spans 34 pages. It builds upon the titular mechanism and the aesthetics of The Sims 2—its color palette, fonts, and icons— but transforms them into a wholly original system of interactions, designed to echo real-life situations and structures. It introduces definitions of interactions, reflections on the factors that influence their choices, and a taxonomy of custom interaction types, including Existential Interactions, Disgraceful Interactions, Scattered Interactions, Romantic Interactions, Tearful Interactions, Social Interactions, Transactional Interactions, Imaginative Interactions, and Virtual Interactions.

As part of the work, I created my own Sim-like alter ego and cataloged my identity using a system of traits: Emotional Intelligence, Hypercorrectness, Chauvinism, and Narcissism. Each trait was measured on a scale from 0 to 10, with its intensity visualized through a familiar Sims-inspired interface of colored points. This approach annexes the mechanisms through which players engage with The Sims, as noted by Thaddeus Griebel, who observed that players project their personalities and values onto their Sims, using the game as a medium for self-reflection and experimentation[5].

See publication HERE

In The Sims, all actions are predefined by the game’s programming, and similarly, in real life, the “choices” individuals face are often shaped by societal structures, expectations, and technological interfaces. As Jessica Baldanza observes, our interactions in the physical world are no more objective than those made in the virtual world[6]. By adapting The Sims 2’s gamified approach to interactions, the work shows how virtual systems can serve as a metaphor for understanding societal norms, internalized patterns, and contextual constraints. Through the prism of the game, it becomes possible to critically examine the surrounding reality, highlighting the parallels between simulated and real-world relationships while questioning the structures that define them.

Creating an online self, designing an appearance, cataloging an identity, and simulating possible interaction scenarios can extend or replicate life. This portrays the online world as a heterogeneous environment that transcends digital boundaries, necessitating the involuntary creation of an ambiguous online self to explore and manipulate one’s identity. It examines how people use available technology to create cues that are interpreted offline to perceive others’ behavior. Additionally, it highlights how online interactions mimic offline interpersonal relationships, leading to the fluidification of identity, the redefinition of relationships, and the blurring of boundaries between online and offline realities.

Life in Simulation: Navigating Between Worlds

Me Living My Best Life (2021) is a video exploration of the blurring lines between physical and virtual realities. It integrates my physical form into the simulated world of The Sims 2. The piece features a recording of me dancing against a green screen, transitioning my physical presence into a digital avatar. Set to the iconic The Sims 2 radio track Dance the Dawn (Salsa), the video embodies a life without boundaries, allowing for an infinite reimagining of self within the virtual realm.

As Ludovica Price notes, what enabled The Sims and its sequels to stand out from other games was the way in which it allowed players to create their own worlds and to embellish others[7]. This core concept of constructing personalized, immersive scenarios lies at the heart of The Sims and served as the conceptual foundation for work. Within the game, I meticulously built all the virtual scenographies myself, designing each environment as a visual backdrop for my performance/best life. Complementary costume changes further reflect situational shifts within these simulated spaces.

Me Living My Best Life delves into the fluidity of identity within alternative forms, where the boundaries between reality and its digital representations become increasingly blurred. As Vasa Buraphadeja and Kara Dawson highlight, The Sims offers players the opportunity to immerse themselves in different scenarios of life—they can take on many different roles and assume several personas[8]. In this vein, work creates alternative realities, reflecting the way both identity and the medium itself become more fluid. The boundaries between the physical and virtual worlds dissolve, allowing images to not merely replicate reality but to transform or even distort it, distancing us from its original essence. This fluidity allows for the exploration of multiple versions of self, liberated from the limitations of the physical world.

The performative aspect of the work deeply resonates with Ana Peraica’s observation that we don’t know how to exist anymore without imagining ourselves as a picture[9]. The act of embedding my likeness within The Sims 2 underlines the profound intertwining of digital and physical identities. It showcases the fabricated and performative qualities of selfhood in an age increasingly dominated by visual culture. By incorporating my image, the piece not only interacts with the game’s well-established practice of crafting personal narratives but also delves into the nuances of digital identity and the conception of oneself as a visual construct. This interplay between self-representation and self-creation highlights how virtual spaces redefine our understanding of identity, portraying it as both fluid, multifaceted, and inherently linked to its visual manifestation.

Life Beyond Simulation

As McKenzie Wark aptly observes, more and more relentlessly, the everyday life of gamers is coming to wear the expression of game-space[10]. This notion resonates deeply with the way mechanics from games like The Sims transcend their digital origins to influence how we perceive and navigate the real world. The Sims series is more than a life simulation game—it is a lens through which to explore the structures that shape human experience. It has become an integral part of contemporary perceptions of identity, where we categorize, visualize, and create algorithms that define and shape how we understand ourselves and others. Ultimately, The Sims serves as both a mirror and a critique—a tool to reimagine the systems we navigate daily and a platform to envision new ways of understanding and expressing the human experience. Through its playful simplicity, it opens the door to profound insights about the complex and interconnected realities we inhabit.

References

[1] Jesper Juul, Half-Real: Video Games between Real Rules and Fictional Worlds, 2005

[2] Ian Bogost, Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames, 2007

[3] Brad Tromel, Peer Pressure: Essay on the Internet by an Artist on the Internet, 2011

[4] Sherry Turkle, Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet, 1995

[5] Thaddeus Griebel, Self-Portrayal in a Simulated Life: Projecting Personality and Values in The Sims 2, 2006

[6] Jessica Baldanza, The SIMS effect: Virtual Identities in Accelerated Reality, 2016

[7] Ludovica Price, The Sims: A Retrospective A Participatory Culture 14 Years On,2014

[8] Vasa Buraphadeja, Kara Dawson, Exploring Personal Myths from The Sims, 2009

[9] Ana Peraica, Culture of the Selfie: Self-Representation in Contemporary Visual Culture, 2017

[10] McKenzie Wark, Gamer Theory; Allegory (on The Sims), 2007