“How Present is Wall”, reads white panel installed in the grassy park in Berlin, tightly fit with five other layers of the same design. Arranged in a zig-zag, the installation ends with: „How Strong is Border“, „How Liberation is Freedom“. None of them end with question marks.

There is one thing that strikes me the most: the middle panel, asking or stating, „How is Longing“. It lacks an adjective. The space between interrogative adverb and present tense verb is empty; but do we really need to fill it with one word after all?, I ask myself.

There is a continuous current of longing and yearning that is difficult to keep straight, yet they stick. They inflate the pool of memories and dive in and out between our selves. And there is toughness to reminiscence: longing stays elastic and steady. I like to think that longing holds us in place, gives us a dwelling place. And sometimes, this is mediated by our choices in how we remember what has already long passed, or perhaps, places around us do the remembering for us and with us.

In 2022, I went to Berlin for my master’s thesis fieldwork to explore the memory-making of German Democratic Republic, in particular, remembrance practices among former political prisoners of STASI and places that stake a claim on memory: museums and memorials dedicated to the GDR period. When having conversations with former citizens of the GDR, I realised that when the „remembering happens“, the bodies of the Rememberers are continuously moulded. The past is rediscovered again and again, with the temporal boundaries – bridging words of „here“ and „there“ that help the memory to narrate itself. Yet, how is longing for places that produce the memory?

Choose your own mundanity

Memory sites are dead material – they are inherently mute, for they hold no memories of their own until people invest them with meaning. In contemporary debates about GDR memory, there is a marked split: on one hand, material remains underscore a state of injustice. On the other hand, some representations tend to showcase naïve sentimentalizing and, at worst, intentional banalising of the GDR past. The German term, Ostalgie embodies the latter, as it is a conflation of two German words: ‘East’ and ‘nostalgia’. Yet, Ostalgie is not necessarily about an obsession with the GDR era, but it rather might be an embattled site of memory-making, where individual experiences and biographies seek legitimacy.

In recent years, there has been a tendency to gloss over the totalitarian past of Germany, reframing the feeling of Ostalgie as a mainstream sentiment. The DDR Museum in Berlin exemplifies this shift. With its approximately 10,000 artifacts – ranging from bottles of kitchen cleansers to speaking windows at the border checkpoints – it presents a collection of mundanity. In a way, it preserves personal memorabilia, but, this type of memorabilia sometimes is emptied of its intimate weight they once carried.

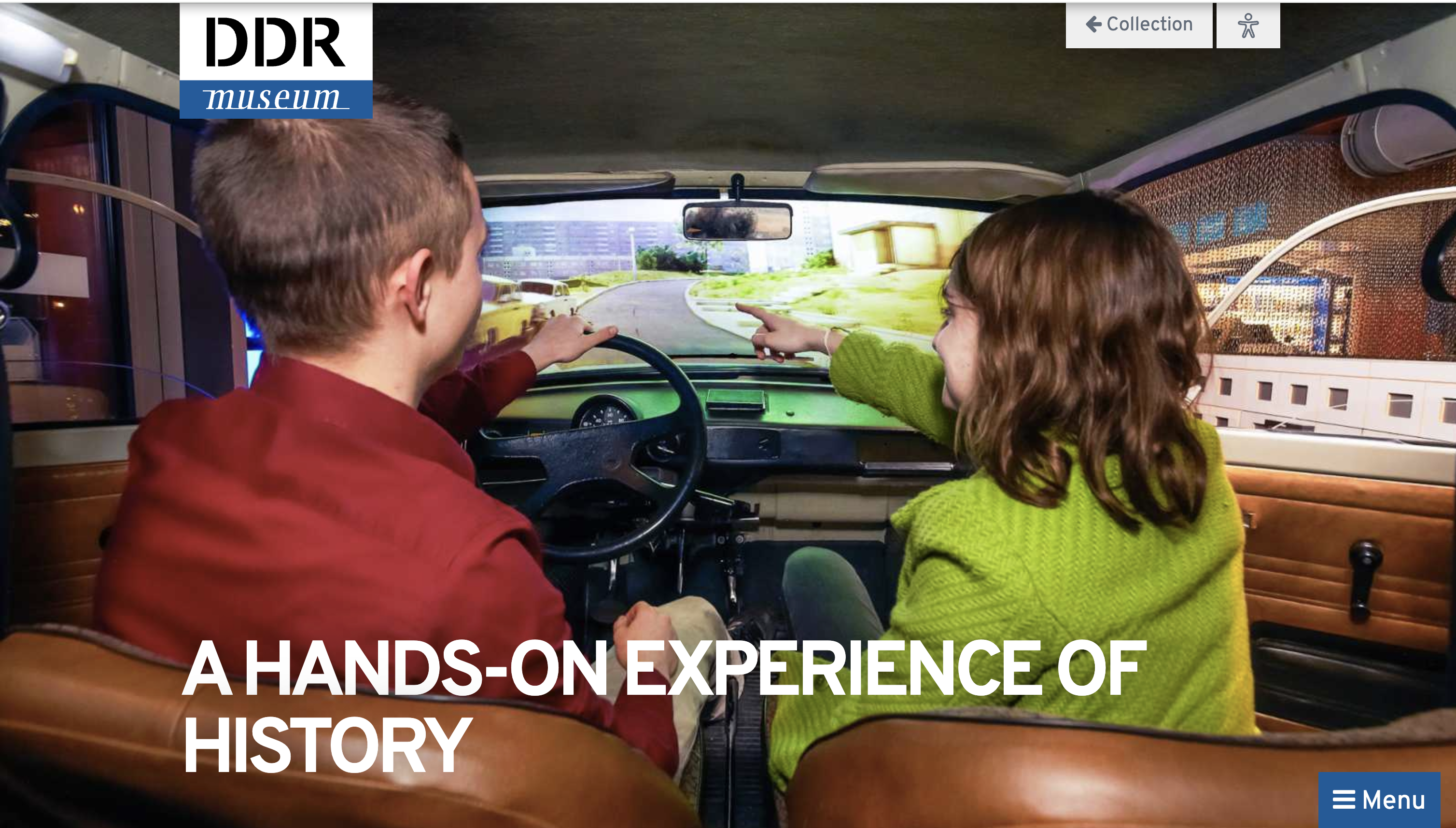

When I was scrolling through the website of the DDR Museum, I saw this little section of how museum introduces itself as a Looking Glass into a „bygone state“. By describing itself as “unique” and “extraordinary”, it seems the museum detaches itself from other, conventional museums. It states, the history, and in particular, everyday life in the GDR is conveyed in “scientifically sound” way, and also sensorially crafted in a way that feels accessible, and even – enjoyable.

Writing such description focused on its extraordinary nature on the website to attract visitors is a conventional marketing language aimed at drawing interest, which is a standard approach. Yet stating it is a “scientifically sound” way to engage with the past is also claiming the memory, but whose, or which memory? What does it mean to be “unique”, or “scientifically sound” anyway?

Choose your own DDR

The interface of the website provides the users with a huge display of two people sitting in a Trabant car, one person pointing to the direction of socialist building from the windshield. The space itself also had a real Trabant car, in which visitors could sit and have “journey back in the GDR”, along with experiencing the “daily life” while entering the rooms of furnished high-rise block tower, taking a seat in front of a small soviet TV in the reconstructed living room typical to the GDR housing, and looking into the reconstructed, “socialist” bedrooms.

Each item there had its own history, which created a drifting experience, but it went to places that are fallen into disuse, and disrepair. These are infrastructures that are failing, but failing in a consistent way, as this failure repurposes itself as somewhat entertaining in the contemporary museum scene. It is clear it is all staged, for raising an awareness, but mostly, for entertaining purpose. The museum almost makes a spectacle out of grey block buildings and the dull weather, that one can see and “immerse themselves into” when on-site.

The reconstruction of the past in such straightforward way was worth of analysis for several reasons: I wanted to see how the museum positions itself in the current memory debate about German socialist past, especially considering its promise for multisensorial experiences: when the visitors can touch, feel, listen, and truly inhabit the space. Soon, I asked myself whether the museum was building a collective mythology, or rather, an entirely new memory, not ex nihilo but out of a fixed understanding of the past remembrance. Interestingly, it lets you choose what to dwell on, what to contemplate, precisely. But doesn’t it also serve as a counter-memory of the past experienced by people who feel their lives were museumified?

One of my respondents once told me he could not bear the boredom of the being anymore, that it was all dull, grey and dreary; that life there had no colours; that buildings had no new windows, that everything was so old and dysfunctional; let alone the greyness of smell – the smoke produced by factories that prevailed the whole East Germany. Yet, in another realm, in the West, people had all the smells and colours, they had all kinds of fruits and that’s where he tasted Kiwi for the first time after the Fall of Berlin Wall.

Another woman I talked to tells me in a concerning tone of voice that there were no deep connections among lovers, „it was not love and sex together, but it was just sex, sex, sex. The boredom of it, no theater and no cinema“. „This endless boredom, it’s something I remember the most“, tells me another respondent, „the scenery was so unbearably boring, even going to the summer houses during holidays, it was so, so boring. No other people around, TV showing nothing interesting. That’s why they drank so much, you know.“

Boredom was a way of living according to people I talked to, and it also served as a state of being – as an antidote to what the West embodied. Yet, I could not see any equivalent of boredom when visiting DDR museum, I saw the past residues displayed there as a different kind of embodiment, these life histories, online and offline are commemorated in a way that the spectacularity is maintained.

Choose your Fighter

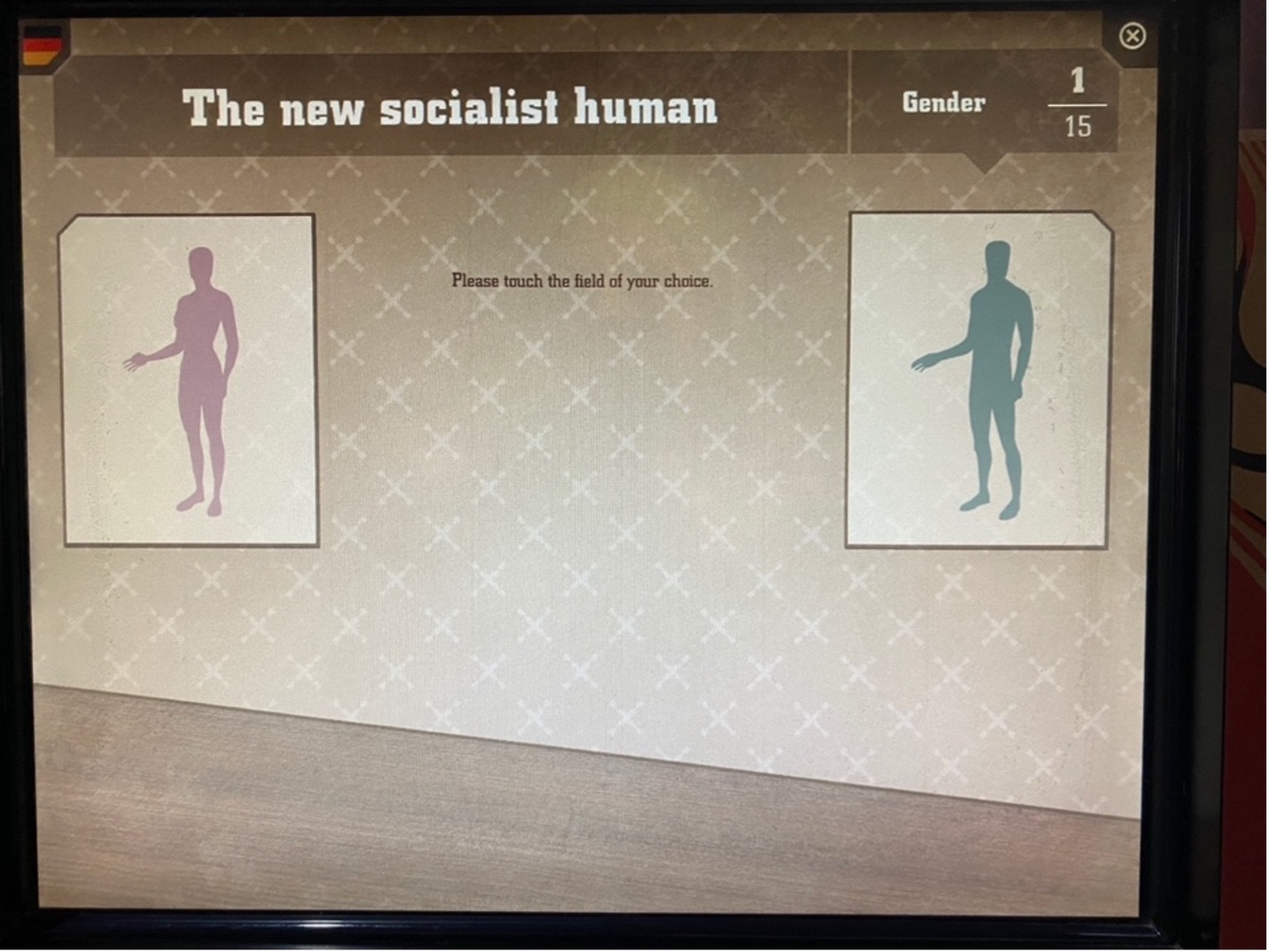

While reading short informative texts about GDR artifacts, its borderzones, and STASI surveillance, a digital screen caught my attention with the phrase: THE NEW SOCIALIST HUMAN, against the background of the Soviet-style wallpaper.

While reading short informative texts about GDR artifacts, its borderzones, and STASI surveillance, a digital screen caught my attention with the phrase: THE NEW SOCIALIST HUMAN, against the background of the Soviet-style wallpaper.

After choosing a field of choice, this type of “interactive game” enabled the visitors to customize a character by choosing a face from four facial expressions. The next step involved selecting clothing for their desired character, again with four options. In case of “pink socialist human”, there were two dresses and two trousers, aimed at „building“ some kind of a GDR persona. Users could also select desired hairstyle (again, out of four options), top, shoes, hat, jewellery, bag, book, accessory, and a flag symbol. Each section provided a brief information. The category of jewellery stated:

„Have you just been released from prison? Piercing and tattoos have no place in the life of good Socialist. Rings are to be worn on your fingers and then no more than a wedding ring.“

Once the character was complete, one could print their versions. The objects, such as Trabant cars, bear the legacy of ideology, yet „taking an artificial ride in the GDR landscape for several minutes“ removes such object from the realm of politics, and such activity with GDR artifact becomes a source of entertainment. But what about actual „humans that represent Socialism“ as illustrated by the museum? Can the complexity of people living in the GDR inserted into a game-like understanding of a person as a whole?

This reminds me of the psychoanalyst, Hans Joachim Maaz making quite a long remark in his work, „Behind the Wall: The Inner Life of Communist Germany“ about the psychological portrait of the collapsed „existing real socialism“ of the GDR. He boldly stresses the „dysfunctional traits“ of East Germans, noting that „the East German personality suffered from the „deficiency syndrome“: deprived of everything from good service to clean air to unconditional love, East Germans invariably blocked instinctive emotional responses and often channeled them into dysfunctional outlets, such as overeating, drinking, smoking, and watching television“. This is quite a risky and stigmatised statement to make, let alone calling „overeating“ (whatever that might contain and however this data was collected statistically), „drinking, smoking and watching television“ a dysfunctional trait.

There is also a universalised term in some disciplines within social sciences, rendering the whole generation to Homo Sovieticus, which also makes me question how these bodies are constructed within the everpresent gaze from Us to Them. And what about digital Socialist bodies we stumble upon from time to time? Reducing a trope of socialist persona to merely four options, as the little screen indicated, might also be museum’s intention to reconstruct the stereotype of Soviet propaganda by offering „fun and rich“ experience of building a new Socialist human within its cultural and political policies. However, considering the complexity of these individuals, this type of reconstruction might have a dual nature: while intending to showcase Socialist stereotypes, this representation becomes disconnected from the actual owners of their political or cultural bodies, or even, personal life-stories they might be embodying. In other words, it becomes a stigma reinforced by stigma.

This digital screen, regardless of what it carries, it serves as a memory carrier. It does create a unified narrative, and it is exclusive of the complex memorabilia of bodies, digital or lived. And it does create new memory site of its own, some kind of an artificial fabric from which we choose our fighters, we build them, we play the game and we are taking a journey in somewhat bygone space full of failures.