Bridge 1

Beginnings are always difficult, and endings don’t really exist. It’s even more difficult to try and put my involvement with the Poland-based collective UKRAiNATV into words, which happened at a very specific time of my life - and the lives of many others. My experience there obliged me to deeply reflect on what it means to be an indirect witness, a collector of stories, and how to try and be a transmitter of those. This text is also an attempt to draw up a theory of UKRAiNATV itself, through the lenses of Susan Sontag’s investigation of photographic evidence and Gerda Taro’s life of resistance. It also contains examples of independent media, like Radio B92, and records of all the people I interviewed in Poland while drafting my MA thesis1The title of the thesis is “UKRAiNATV e la Streamart: Esempi di Artivismo, Giornalismo d'inchiesta e Sperimentazione Artistica”, written during my stay in Amsterdam for the Net Art Master at Brera Academy of Fine Arts in Milan, Italy. .

In 2024 we are witnessing a series of crimes against humanity, on a scale and intensity sadly traceable to something we thought buried in history, a bad memory that would serve as a warning to future generations. Cultural practices are no strangers to these happenings, they are active representatives of geopolitical phenomena (Russia's exclusion from the Venice Biennale in 2022). The war perpetrated by Russia, which had the worst of consequences on February 24, 2022, with the full-scale invasion of Ukrainian territories, kicked off a series of horrors that still resonate in news channels today.

In September 2023, I moved to Amsterdam from Italy, where I have now spent 10 months adjusting to the climate, taking vitamin D supplements, and improving my waterproof wardrobe. Surprisingly, the transition itself felt smooth and seamless. After nearly a year of working with UKRAiNATV - an art collective based in Kraków that experiments with live audiovisual connections - I began interning at the Institute of Network Cultures. UKRAiNATV started their activities in March 2022, expanding its reach to other similar communities as early as November 2022. That same month, Geert Lovink visited the studio. Since then, our main goal has been to expand a shared network between UKRAiNATV and INC. By working together, we found it easier and far more effective to raise funds in support of our allied partners operating in Ukraine, who have struggled to maintain a working studio since the beginning of the full-scale invasion. This network we've been working to establish and nurture over the past year and a half has now taken its shape, with 4 stable nodes: Kraków, Amsterdam, Budapest, and Kyiv. Here in Amsterdam, I started collaborating with THE VOID, an INC research project on tactical video and an audiovisual publishing venue for practice-based research. This place has become my "home base," and it's where I want to start sharing the research that has absorbed me over the past year and a half.

In June 2024, while UKRAiNATV was taking part in the Sonar festival (Barcelona), I joined them in an online roundtable together with Tommaso Campagna and Geert Lovink from Amsterdam. The participants also included János Sugár from the Hungarian University of Fine Arts (Budapest), Alyona Ivanova and Vlad Kononok, representing their collective RE: Frame.TV (Kyiv), and Gleb Dovzuk from UKRAiNATV's studio (Kraków). This meeting underscored the importance of our network's connections once again. The presence of all the participants, even if online, strengthened the acknowledgment that we're not alone.

Enlarge

In May of the same year, during THE VOID T.V. – Tactical Video #3, an online call with Ukraine was disrupted due to issues with the electric generators in their studio. The situation in Kyiv has in fact worsened, with citywide power outages leaving residents about 4 hours of electricity daily. Given the urgent need for immediate support actions and the archival efforts our colleagues in Kyiv - particularly in documenting system failures - I increasingly recognized the importance of maintaining an independent, on-the-ground network of connections. This network, centered on immediate sharing and filtered through the communications happening within each circle, is crucial for establishing a more diverse framework, in an era marked by the growing polarization of information sources.

Enlarge

Though the timeline has been a bit jumpy, I need to return to the beginning of the story. From September 2022 to June 2023, I had the opportunity to participate in a nine-month cultural exchange program in Kraków, Poland. During my studies at the Academy of Fine Arts (ASP), I met the activist art collective UKRAiNATV, which in conjunction with the outbreak of war in Ukraine, began mobilizing in support of Ukrainian refugees crossing the border. In the months following - February and March - the basement of Kraków Główny was filled with displaced people: women and children mainly, crammed into the station, sleeping on the floor and makeshift beds.

Enlarge

A similar image could be seen in Warsaw. Hearing the testimonies of those who experienced these events of war and having to flee firsthand allowed me to change my understanding of an emergency – from being witnessed from afar, to being close to it. Geographical proximity soon turned into emotional closeness. This newfound empathy allowed me to take an interest in historical events that did not belong to me as I thought they were. I was turned into a more active participant in the consequences of a war that is continuing even now, 2,393.0 km away from where I was living at that time, in Italy. UKRAiNATV activities began shortly after, and initially focused on raising funds and collecting resources, as immediate support for Ukrainian refugees arriving in Poland. By organizing events - often in synergy with local artists - and posting them as live streams on their channels, they started to create a support network. The studio is situated in the Intermedia Department of Kraków’s Academy of Fine Arts. Perhaps this network of support - of which I was not necessarily the primary recipient - saved me when I arrived in Kraków as an Erasmus student, trying to escape my own troubles, though certainly not a war.

At first I needed a place where I could use the Virtual Reality setup for an event organized for the Digital Week in Milan. Me and some colleagues from Italy were working on a VR project, and since it was going to be exhibited during the festival’s day, I was looking for a studio to arrange the virtual connection. Ultimately, I ended up being in the UKRAiNATV studio most of my time, taking care of the virtual space design, and creating environments that could be inhabited during the special events and weekly streams. This gravitational pull captured me. I had been searching for a place like that for a long time: a collective of people involved in art, politics, tea ceremonies, raves, and events. I was not even speaking the language, so I certainly didn't expect to be quickly incorporated into that strange and somewhat crazy melting pot. And I certainly didn't expect to deal with the war, or rather war stories of it, that the people who walked through that space carried with them.

After almost two years of Russian colonial warfare, UKRAiNATV now presents itself as web-tv platform that operates offline and online (on a conglomerate of platforms such as Twitch, YouTube, Facebook, etc.). Once a week, on Thursdays at 6 p.m., it streams a couple of hours of live performances, videos, interviews and DJ sets - giving a stage and a bullhorn to a series of guest visiting the studio. Each episode is categorized under the name #EFIR2Efir, transl. ether, it stands for the medium in which these episodes circulate, the air, and symbolizes the lightness that characterizes the group. The word ether or efir was borrowed from Greek into Old East Slavic.. The headquarters are at the 23rd of Berka Joselewicza, in the Intermedia Department of the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow.

From the outset, the space itself offers a unique environment where the collective provides a place for newcomers. Since November 2022, the group has been working to expand its network. Through collaborations with various institutions and research centers, it has raised funds and supported artistic research groups in Ukraine, all while maintaining a focus on a war that shows no signs of ending soon. In a short time, the collective identity has become increasingly defined, starting with a Manifesto, and progressing through the exploration of the streamart. This practice is here described as a set of hyperactivities engaging with both the digital and physical domains. By blending people and machines, hardware and software, infrastructures, and performances, a new aesthetic emerges. Streamart represents the dynamic and continuous flow of energy in hybrid spaces and times, encapsulating the entanglement of human and non-human entities. In this context, the virtual is seen in its potential form, while keeping grounded in the coziness of the studio.

Bridge 2

The concept of the streamart was a central theme in my master’s thesis I was writing for Italy (UKRAiNATV e la Streamart: Esempi di Artivismo, Giornalismo D'inchiesta e Sperimentazione Artistica3Translation: UKRAiNATV and the Streamart: Examples of Artivism, Investigative Journalism and Experimental Arts. ), evolving from early telematic performance4https://doi.org/10.1386/jmte.10.2-3.257_1 to contemporary streamer culture. But I also wanted to understand the link between the collective's practices and the political significance of its activities. During my months of research, I discovered Radio B92, a powerful example of independent media existing under an oppressive regime. This renowned activist institution has made a significant impact on the Serbian media landscape, highlighting the importance of independent journalism during wartime. Founded in 1989 in Belgrade, it became a beacon of free expression and independent journalism during the years of the Balkan war and the fall of the Milošević regime. The station provided a platform for diverse and often dissident voices, broadcasting alternative music and real-time news that defied government censorship. Its history was marked by an extraordinary commitment to press freedom and civic activism, becoming a symbol of resistance and hope for Serbia and the international community.

Enlarge

During the war years, Radio B92 was one of the few sources of independent information, broadcasting unbiased news that was often at odds with state media propaganda. The station also maintained critical coverage of the facts, offering a different perspective and encouraging dialogue between the parties.

Enlarge

Because of the Milošević regime's censorship, the station suffered the blocking of its signal. However, it managed to broadcast via satellite from abroad, thus continuing to reach Serbian audiences and the ranks of the resistance. In addition to broadcasting information, Radio B92 also played a key role in introducing alternative music and underground culture to Serbia. It promoted local and international artists, providing a platform for creative expression outside the limits imposed by the regime. Matthew Collin, the author of "This is Serbia Calling”, writes5Variant, no. 22, Spring 2005, ISSN 0954-8815. Variant is an independent magazine that addresses issues of culture in the sociopolitical context of various countries, and a nonprofit association funded through subscriptions from magazine subscribers.:

By the time I got there, ten days after it all kicked off, there was about half a million people in the streets demonstrating against the theft of election results by the government of Slobodan Milosevic. But there was another element to it; it wasn’t just a political demonstration, students marching on the streets, just civic unrest, it had another ‘cultural’ element to it—music, film, art were all important to this. There were a lot of ways that messages were being transmitted, not just through your classic placard that you see on every demonstration, but in a really creative way, and this is what inspired me to get involved6Collin, Matthew. “Don’t trust anyone, not even us”, pag. 9 di Variant №22, primavera 2005. https://www.variant.org.uk/pdfs/issue22/B92.pdf..

What Collin emphasizes here, is the way activism and counterculture spontaneously worked synergistically to raise their voices against a regime that was oppressing them. These two worlds have often worked in sync, though not always with positive outcomes. However, history records several instances where underground cultural entities have facilitated social and cultural revolutions, such as Pirate Radio in the UK during the 1960s. Collin, in the same article of Variant № 22, continues:

"Those demonstrations failed, as we all know, and some people argue that just being out on the streets in numbers and just creating a cultural alternative is not enough, that you actually need more power than that to get your message across. It took another four years for the ultimate goal of this protest movement to be realized, which was the overthrow of Milosevic, but it was a beginning."

Enlarge

I now had a historical reference for understanding the political dimensions of UKRAiNA TV, that helped me understand the independent media scene better, especially in the context of war and repressive regimes. Yet, I still had questions about how to represent that pain on screen: what about the interviews recorded in the studio? Or, for instance, the very use of a visual element to preserve those collective memories?

Bridge 3

Wanting more, I looked carefully into others' work and research, finally coming across two of Susan Sontag's main writings: On Photography (1977) and Regarding the Pain of Others (2003).

Sontag analyzes how photographic images change our perception and understanding of the world, highlighting their potential both as a vehicle of knowledge and as a tool for manipulating reality. The book focuses on the idea that photography can be considered a form of critical documentation, as it captures snapshots of life, thus revealing a hidden side of the world.

In Regarding the Pain of Others, Sontag delves deeper into the portrayal of pain and suffering in media and art. The numerous images of conflicts featured in her book, particularly those from wars contemporary to her, such as the one in Kosovo, serve as crucial evidence of recent horrific events and potential future trials for human rights violations. While photographic documentation holds significant value as a political and commemorative act, Sontag opens the floor for a reflection on its controversial aspects. Today more than ever, the widespread dissemination of war images via TV and social media highlights these controversial aspects vividly. From the Russian invasion of Ukraine to the ongoing genocide in Gaza, photography and video serve as an important visual testimony to civil suffering and human rights violations. They become a visual testimony to human suffering and the chaos of war. Photographers working in these conflict zones face complex ethical dilemmas, trying to balance the desire to document reality with the awareness not to turn human suffering into a sensationalist spectacle.

Another point Sontag discusses is the ease with which a photo can be manipulated or repurposed, a factor that should not be overlooked. The improper use of visual documentation is a crucial aspect of the dissemination of news in real-time. In her book, Sontag gives the example of a photograph showing the bodies of murdered children. This same image was then used by the opposing side, to motivate soldiers to battle, instrumentalizing the sight of slaughtered child bodies for their cause. One could draw a modern parallel to the destruction of the Al-Ahli Baptist Hospital in Gaza on the evening of October 17, 2023.

Although more than fifty years have passed since the events recounted by Sontag, and technology has advanced in no small measure as the amount of evidence gathered at any moment, we still struggle to establish the truth about who was the architect of this massacre. A myriad of videos and images open the same questions as a photograph taken during the Yugoslav wars. Or at least, this is still the main argument major media press and political figures use when asked about the facts. The evidence seems not enough, and even if it was, would it justify the atrocities occurring before our eyes?

Bridge 4

After finishing Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others, I found myself reading Helena Janeczek's7https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helena_Janeczek. “The Girl with the Leica” (2017), which was sitting in the upper corner of my library for more than I could remember. These serendipitous moments often occur when collecting articles and books for research. Assuming the woman winking on the cover of Janeczek's book was a photographer, I connected the two. As I read further, this seemingly minor link became a fortunate coincidence.

Enlarge

Gerda Taro, born Gerda Pohorylle, was a photographer and pioneer of photojournalism during the Spanish Civil War. Of Jewish descent, she worked closely with Hungarian-born photographer Robert Capa, and together they documented the horrors of the war and the devastating impact of the conflict on the civilian population. Helena Janeczek's "The Girl with the Leica" rescues Taro from the shadow of oblivion cast by her illustrious partner, Robert Capa. Taro's dedication to capturing the grotesque and tragic aspects of war serves as a testament to her unwavering resolve. Positioned on the front lines, her lens became a witnessing tool, confronting the gender biases of her epoch. Janeczek's narrative peels back layers of Taro's existence, revealing a life interwoven with courage and a relentless pursuit of authenticity. The account also resonates with the vibrant and affirmative essence of Gerda, as echoed by the voices of those who fought alongside her.

Janeczek's book exists in the interstice between a novel and an investigative biography. As a journalist herself, she reconstructs the everyday life and almost romantic facets of Gerda’s existence. This intimate portrayal, however, does not diminish its validity; the subjective narrative enhances rather than undermines the cultural significance of Taro's story. What impressed me the most about her, is well explained by Sebastiaan Faber, as “(…) a complex, multivocal historical novel that is less a portrait of Gerda Taro than of her entire milieu: young, antifascist, bohemian, refugee, free-thinking, emancipated, and rife with short-lived romantic entanglements”. In my reading of Janeczek's book I still find striking the vital force that Gerda embeds. She sticks anti-Nazi leaflets on the streets of Berlin on a moped with headlights off, and at the same time, she populates Paris’ intellectual cafes in cute dresses, giving coquette bottles of perfume to her adoring lovers. She decides to go to the front to document the Spanish Civil War, and simultaneously takes photographs of soldiers playing with birds. She documents women training to fight on the bank of a river, and this whole set of features comes across as dissonant, almost scandalous.

Enlarge

Clearly, the actions of a young, spoiled girl, ready to throw her life away for a bit of action. This thought comes up because what we see here, is very different from what we want to see. The condemnation of war’s horrors is much louder when they are outside the field of the camera's viewfinder. What we can see, it’s how it should be. And, nonetheless, she also photographed the horrors. But it’s her zest for life, juxtaposed with her premature death, that deeply inspired me and added greater significance to my involvement with UKRAiNATV. With her very existence, she juxtaposes the sacred with the profane, not giving up on leisure even during the war. These elements, which at first seem dissonant, reveal their necessity when one is entrenched in conflict. This method of blending seemingly disparate elements produces a shift in the usual narrative. In UKRAiNATV’s events, colorful visuals and psychedelic DJ sets are intertwined with topics of war. This approach captures attention - an incidental effect - and, more importantly, induces a form of catharsis. By making the grim subject (war) more accessible and impactful through unexpected forms, barriers to emotional expression dissolve. There is no judgment; the physical proximity allows everyone involved to express their emotions freely, however, they feel is right. This stance is radical: we are doing this for ourselves, to find some solace in a horrific situation. We deny anyone the right to dictate how we should feel (for ex. If you feel sad, show sadness). We don’t adhere to restrictive norms that seek to simplify and regulate our complex emotional responses.

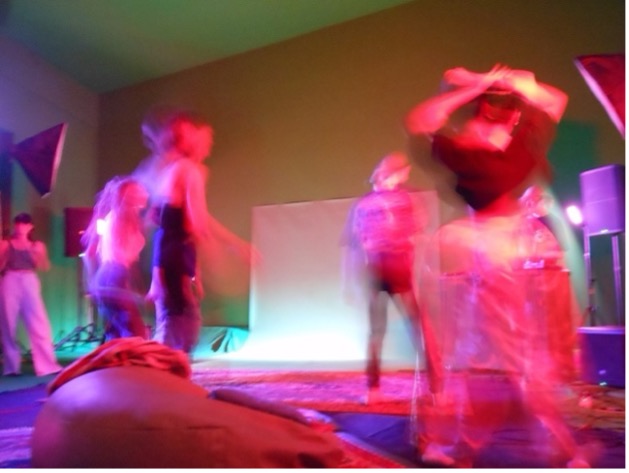

On the day that marks the second year of colonial war in Ukraine, we organized a 24-hour event in our studio, where musicians, performers, and artists were invited to play, hold each other, squeeze, have fun, talk, hug. I always wondered if this way of operating wasn't indelicate for those who copulate with their grief in different ways. However, the people around me, were the same with friends and family living in Ukraine, some of them on the frontlines; or they were political refugees from countries aligned with Russia (Belarus primarily). For them, it seemed to work.

Enlarge

Gerda Taro died in a tragic accident while covering the Spanish Civil War on July 26, 1937, at the age of 26. While documenting the Battle of Brunete, she was run over by the tracks of a friendly tank. On her 27th birthday, August 1, 1937, a state funeral was held in her honor in Paris, where she and Capa had lived and worked for many years. Her funeral drew a large crowd of friends, fellow photographers, and anti-fascist supporters. Her untimely death deeply moved the international community, which initially elevated her as a martyr in the fight against fascism, though she was soon mostly forgotten. Her work and legacy have been recovered over time, thanks in part to the discovery of a briefcase containing a series of negatives taken by Gerda herself, which have made it possible to give motherhood to the photographs produced simultaneously with Robert Capa, and which have often been wrongfully attributed to him, with whom she worked closely. In an interview Helena Janeczek gives during Festival Letteratura di Mantova, she says:

"After discovering her, in Milan, in the first monographic exhibition dedicated to her, I got an excellent biography (...) and made contact with the author, Irme Schaber, who also devoted herself to the reconstruction of the photographic corpus. In fact, Capa's and Gerda's photos were mixed up; it was a very long job to succeed in restoring the correct attributions, an effort that, with the discovery of the so-called 'Mexican Suitcase' containing a large part of the negatives taken by Gerda Taro with the Leica, took a great leap forward. (...) I was clear from the beginning that I did not want to write the classic biographical novel about Gerda, to tell only the story of Robert Capa's girlfriend and the heroic photojournalist who died in Spain in 1937. I wanted to tell it through the eyes of others."

Enlarge

Her contribution to international photojournalism was later recognized as fundamental to the historical understanding of the Spanish Civil War and the role of women as photojournalists. Although her life was tragically cut short, the impact she had in the field of war photography continues to inspire.

If the lure of photography is the promise of unvarnished documentary truth—a chemical imprint of reality as it is at the moment the shutter release is pressed—photographers and their editors have always known that this promise is deceptive. Precisely because they capture the details of a singular moment, photographs call attention to what they leave out: everything that precedes and follows that one moment—and everything that’s outside the frame8https://readingintranslation.com/2022/01/31/helena-janeczeks-the-girl-with-the-leica/..

Enlarge

In giving shape to this discourse, I must go back to Sontag, precisely to her theater adaptation of Beckett’s "Waiting for Godot”. She describes her experience in “Waiting For Godot In Sarajevo”, published by the Performing Arts Journal, Inc.

I went to Sarajevo in mid-July 1993 to stage a production of “Waiting for Godot” not so much because I'd always wanted to direct Beckett's play (although I had), as because it gave me a practical reason to return to Sarajevo and stay for a month or more. I had spent two weeks there in April, and had come to care intensely about the battered city and what it stands for; some of its citizens had become friends. But I couldn't again be just a witness: that is, meet and visit, tremble with fear, feel brave, feel depressed, have heartbreaking conversations, grow ever more indignant, lose weight. If I went back, it would be to pitch in and do something.

In these lines, I discovered more of the common thread I began to unravel while linking everything to UKRAiNATV’s activities. Sontag's words convey the frustration often felt by those who document events and the lives of people they care about yet feel powerless to influence the course of history. The practical reason Sontag mentions here is rooted in her experience with theater. It seems counterintuitive to suddenly relocate to a besieged city to direct a play while most of the population is living in fear and scarcity. But Sontag and a group of local artists decided to get involved in culture, while the city was burning. The idea of responding to violence with culture, the most abstract and seemingly useless expression of man's activities, has something unique in my eyes. We do not feed on bread alone, and especially in the darkest of circumstances, it is not just material help that saves us. Another point Sontag addresses in her writing is a question she frequently received about her choice to perform that specific play: “(...) was it not depressing for the Sarajevo audience; in the sense that it was not pretentious or insensitive to stage Godot there?”. She reflects on how outsiders, asking these questions, completely misunderstood the experiences of those living in Sarajevo at that time. She continues:

To respond to journalists' attentions, when one would rather be doing something else, is inevitably to find oneself saying things, or be reported as saying things, that seem inane or simple-minded. (The questions that provoked these state-ments are invariably left out.) -Why did you come? -To express my solidarity with the people of Sarajevo. -What are you trying to accomplish? -Make a small contribution to cultural life here. -Why Waitingfor Godot? -Because it's a great play. And it resonates here. -Isn't it a metaphor? I know you've written about metaphor. -No, it's not a metaphor. -Well, then, what's the message of Waitingfor Godot? -There is no message. -Well, what is your message in doing Godot? -I don't have a message. -[Same question, repeated more emphatically.] -That it's possible to come here. That other people should come and work here. -Weren't you afraid to come? -Anyone who isn't afraid is crazy. -Why don't you wear your flak jacket? -Nobody who lives here has a flak jacket. I think it would be indecent for me to wear mine. -Aren't you afraid? -[Sigh.] -Is this a political act? -I think of it as an act of conscience. -But you do have political opinions. -Who doesn't? -Are you for intervention? -Absolutely. -Why do you think other people like you don't come? -[Various diffident or testy answers.] And so on.9https://www.jstor.org/stable/3245764.

Sontag’s words resonated with me deeply: her portrayal of Sarajevo closely mirrors what I observed while collaborating with people from Ukraine, regarding life during the war. I feel a strong connection to those who strive to keep the cultural scene alive during times of war. The experiences of those living with the constant threat of bomb scare for the past two years echo the suffering of victims of indiscriminate attacks long ago. It’s in solidarity with those who are resisting every day.

I’m writing this down, and from the belief that cultural practices can help us establish horizontal alliances, based on the equality of the participants; and to develop a bond of empathy with those around us. Perhaps I can describe the sense of closeness I've developed with some of the people I met in the studio through a personal anecdote:

The process of preparing for an EFIR, where most people involved were not aware of the specifics of such a production or what roles everyone was responsible for, was projecting us into a moment of performative existence, which stayed along even once the ‘play’ was over. It felt like we were speaking the same language for a moment, working together on a common goal that required complete trust between all participants. Like a psychedelic trip - that maintains its clarity in our imagination for a long time after the end of its effects - we were reborn in a new ensemble, where that special reality we shared in the studio, still existed. When going outside for a celebratory cigarette, the conversation flowed much more seamlessly. It felt like we were sharing a secret; as if we just stole some apples, and now we were taking our breath after a rocambolesque run. Our eyes sparkled in the semi-darkness of a dusty barn, and we were happy. Up-to-no-good connection. There is now an unbreakable oath between us.

Sontag's visit to Sarajevo had a profound impact on her, which she later documented in a series of essays. Her engagement and observations of the conflict contributed to a broader discourse on the responsibility of media and individuals in the face of suffering. Her work remains influential in discussions about the ethics of war representation and the impact of images on our understanding of global events.

Enlarge

Bridge 5

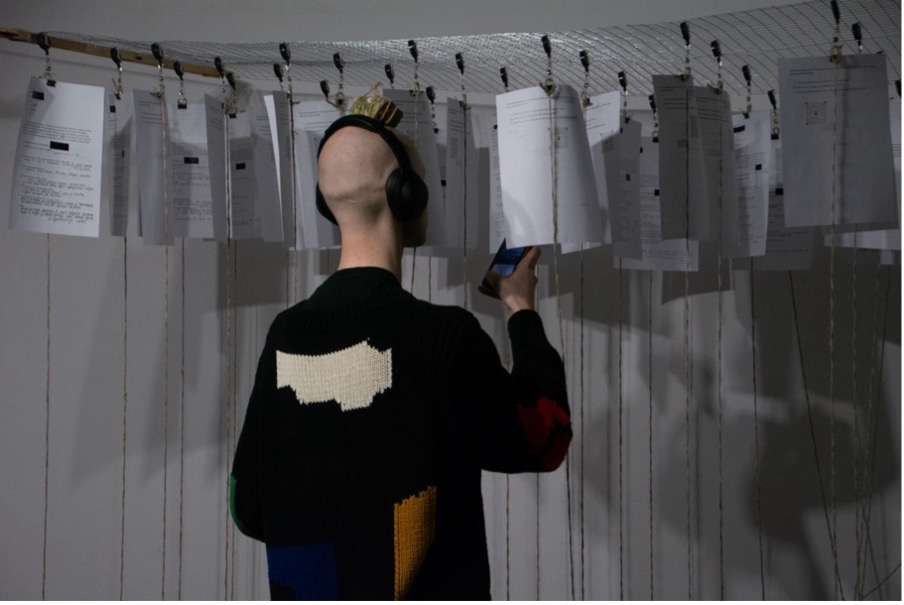

Taro employs photography as a means of resistance, while Sontag expresses herself through writing and directing plays. Inspired by their practices, I sought to develop my own. From April 2023 to February 2024, I conducted an interview project. I spoke with 40 individuals about the events of February 24, 2022, the day the war in Ukraine broke out. The idea came to my mind during the event we organized in UKRAiNATV’s studios to come together after 1 year of war in Ukraine. While smoking a cigarette in the courtyard, someone asked me: “Do you remember what you did that day?” I had no idea. So, I decided to ask around. The research involved 4 focus groups: Poles, Ukrainians, Belarusians, and expats. The interviews are in English, both because it was the easiest way for me to communicate, and to ensure their accessibility to a wider audience later. Just one was entirely in Ukrainian. The project aimed to reflect the complexity and diversity of conflict-related experiences, thereby broadening the listener's perspective. The initial idea stemmed from a desire to pursue research in the context of the war in Ukraine, using as a starting point my perception of the war, and how it changed during the time I lived in Poland (much closer to Ukrainian borders and culture than Italy). My starting argument was that, given the geographical proximity and the presence of a community of political refugees and displaced people from neighboring former Soviet countries, my understanding of the war in Ukraine changed at a higher speed.

Throughout several conversations with Erasmus students my age, but from very different geopolitical backgrounds - Germany, Lithuania, Czech Republic, and so on - the realization that information we often consider objective is inevitably mediated by the informational channels of different countries, grew stronger and stronger. I was interested in understanding why certain positions were so strong, such as those concerning the provision of humanitarian aid to Ukraine by individuals with no direct involvement in the situation yet expressing strongly held viewpoints on the matter. To try and give a more concrete form to these reflections, I decided to draw up a form to be submitted to a sample of 40 respondents, from the 4 macro-groups mentioned above: Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, and Expats.

Enlarge

Several trends emerged during the interviews, which were conducted privately in one-on-one meetings, generally in quiet places, allowing a private conversation. It should be noted that the interviewees were not aware of the main topic, which was whether they remembered February 24, 2022, the day of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. This was disclosed only in the second part of the conversation. The reason for this choice was to prevent the subjects from manipulating their answers according to the topic, somehow undermining the spontaneity of the interview. I knew this decision could be ethically contentious, and some people might find it troubling. Fortunately, those potentially more sensitive to the topic (Ukrainians, Belarusians) did not express discomfort when posed with the question; instead, they emphasized the importance of discussing it. Conversely, groups less closely connected to the subject matter (Expats, Poles) encountered greater challenges with their responses. This could be attributed to either a lack of clear recollection, leading to a perceived manipulation of memories by participants, or because the question itself stirred discomfort.

This is not a sociological or scientific study, there is no basis for conducting it; my intentions during this research were mainly three: to outline a trend, provoke reflection, and create an archive of memories. The first objective addresses a primarily personal need: to engage with diverse individuals and understand the potential points of agreement and disagreement.

Each interview consisted of two distinct parts, ensuring a comprehensive and articulate view of the interviewees' experiences. The first part, a detailed and related image form, provides an in-depth analysis of the interviewee's habits and personal characteristics. Participation in the project is done consciously, with each respondent initially deciding whether to consent to the disclosure of their data, specifying which aspects (audio, video, bio, etc.) could be disclosed. I decided at a second stage to remove the Country of origin so that the viewer would not come to hasty conclusions based only on it. My thesis with this first part was to place the viewer in front of a series of very different biographical records in which to, nevertheless, mirror themselves. The curiosity in knowing the most personal details of a stranger (What is your favorite place here? How often do you see your family/friends?) has always had something fascinating in my eyes, and I thought it might prepare the viewer for the second phase of the interview.

The second part of the form involves a spoken interview, broken down into three key questions:

The goal of this second part was to prompt those being interviewed, and future listeners, to reflect on the subjectivity of their memories, even in broader contexts such as the onset of war.. This second phase somewhat reinforced my initial thesis, namely that the geopolitical proximity of the groups of Belarusians and Ukrainians, and sometimes Poles, had indelibly carved February 24, 2022, into their memories. For the expats, among whom I place myself, this memory was often blurred.

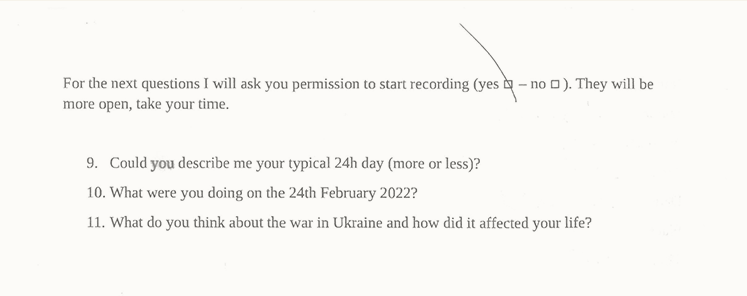

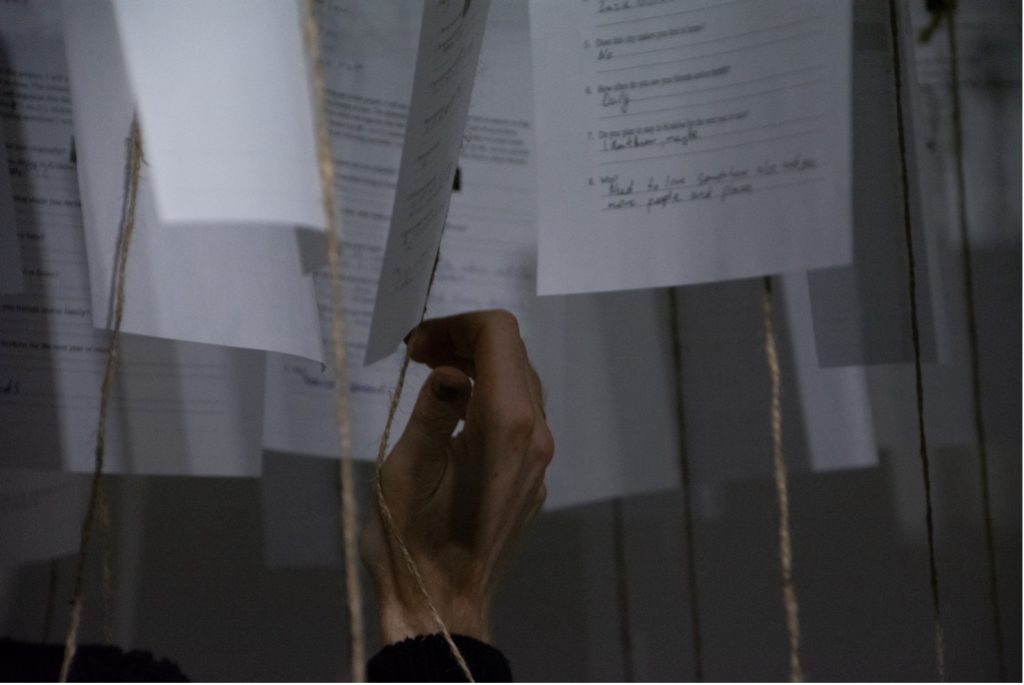

The third and ultimate objective was to establish an archive that would compile the memories of the Kraków community surrounding me during that period. The initial presentation of this collected material took place in June 2023 at a group exhibition held within the Intermedia department of the ASP Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków. For this inaugural exhibition, the interviews were printed on forty individual sheets of paper and suspended from a framework composed of wire mesh and three wooden beams affixed to the gallery ceiling.

- Figure 15: Pictures of the first exhibition of the “24 February, 2022” installation, featuring Konrad Wojnowski.

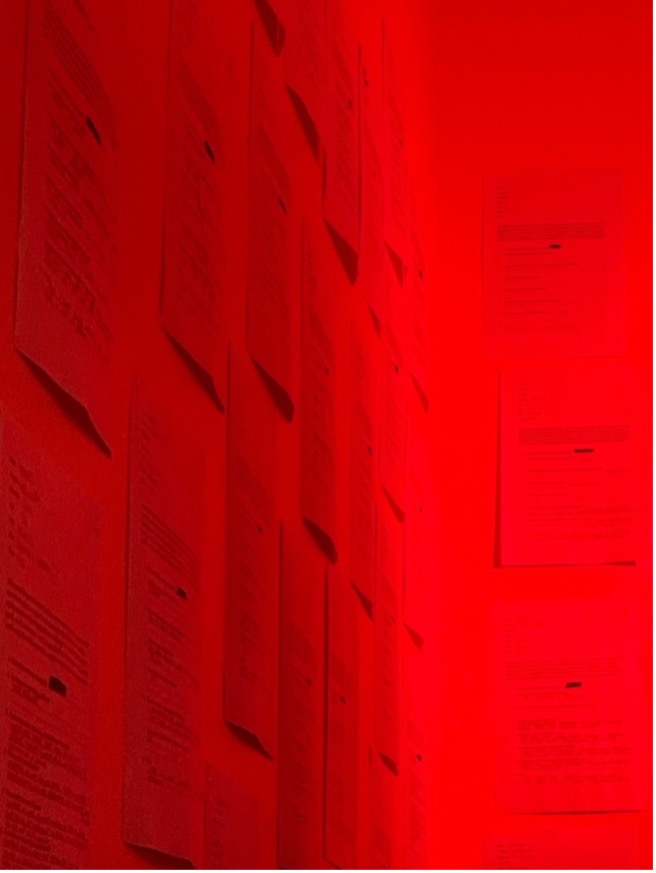

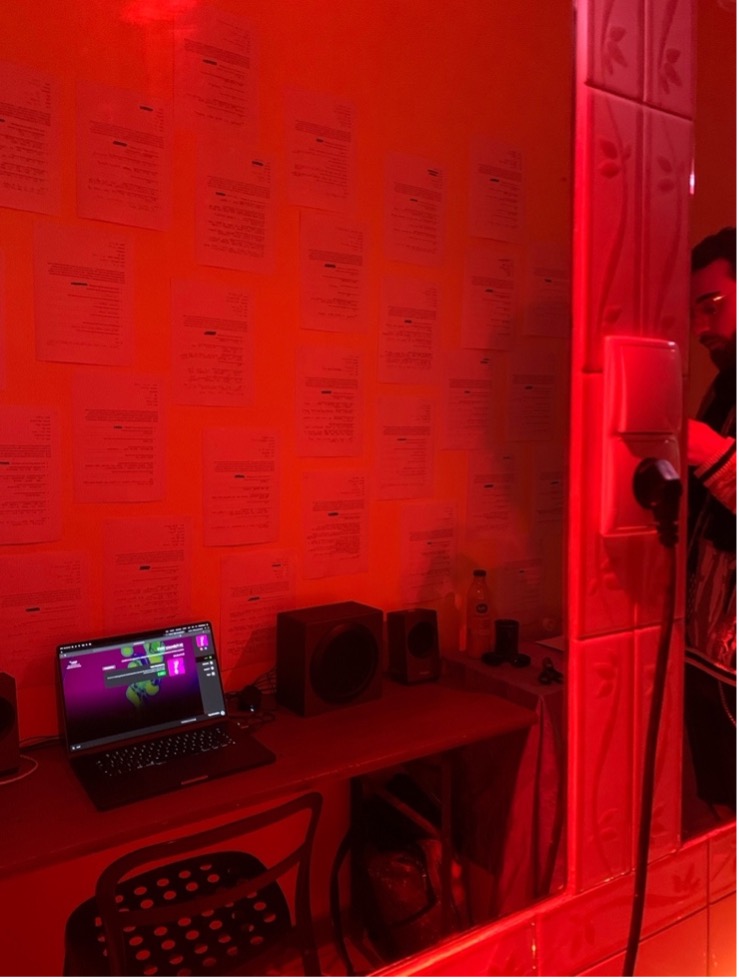

For the second exhibit, I developed a web radio10using the provider AirtimePro.. The event began on midnight of February 23, 2024 - at the same time as the UKRAiNATV livestream set up for the second year of the war. The radio program consisted of a continuous stream of the full edited interviews, lasting a total of 6 hours and 22 minutes, looped, and randomly replayed for the next 24 hours. In parallel, the project engaged the public through interactive programming, allowing visitors to the venue, set up in a room adjacent to the main studio, to participate by giving an interview in turn. Participants then had the opportunity to share their stories on the web radio, thus expanding the diversity of voices represented in the event.11[1] using the provider AirtimePro.

- Figure 16: Pictures of the second exhibition of the “24 February, 2022” installation during the 24-hours event in UKRAiNATV’s studio.

The installation had two main goals: first, to stimulate reflection regarding the ongoing conflict in listeners, highlighting the importance of an empathic connection with the reality of war; second, the project aims to counter the process of media de-humanization by promoting empathy through the testimonies collected.

One of the sources of inspiration for this project was the work “ by Ukrainian artist Timothy Maxymenko. His project consists of creating sound portals through custom-built loudspeakers, then sent to three different Ukrainian cities-Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Odessa. Every day, for 24 hours, with the help of a special mini-computer and microphones located in each of the boxes, the recorded sound is streamed and broadcast live on the portals' dedicated website.

Enlarge

I could not help but imagine an ideal analogy with the work of B92 and pirate radio projects as well, as I thought about the best way to share the collected interviewees' memories. In general, the project's purpose was to confront listeners with their position, of privilege or otherwise, regarding a war that is still ongoing in Ukraine, and that touches each of us on very different levels. It is also meant to strive for us to remember, through the testimonies of people unknown to us, but whose reality we can try to learn about, and slow down that process of dehumanization that mass media usually produce. Empathy toward another human being mediates the experiences of war easier to feel unrelated to. But it’s not. The trends that emerged during the conversations underscore the variability of perceptions and memories related to conflict, illustrating the intricate nature of our recollections, even concerning events we might regard as universal.

My personal experience with UKRAiNATV encompasses a set of practices rooted in artistic resistance, like those described here. This is just my account, yet similar realities exist everywhere: where performance, streaming, photography, radio, and writing serve as forms of grassroots resistance, signaling to the world. Even if the contents made by the group are uploaded on different platforms, it transcends being merely an archive. Events unfold live, maintaining at the same time an ongoing performative element. This blend fosters a new mode of networking, both online and offline, with a political drive and a dedication to memory collection. It becomes a media repository, an active archive online, and an artistic collective offline. This synthesis creates a collective media where streamart and various forms of expression converge, embodying a form of resistance and defiance against academic language and common sense.

Through the analysis of these, all emerge as pivotal figures, whose task – sometimes rooted in privilege - is to amplify experiences and testimonies that might otherwise fade into obscurity. In a world often scarred by conflict and injustice, their mission became constructing bridges of understanding and solidarity, contributing to a more inclusive and liberated future for all.

- Figure 18: Pictures taken during the 24-hours event.

Giulia Timis is a visual artist and researcher whose practice focuses on virtual reality and 3D animation, blending digital environments and performance. In her work, she crafts immersive spaces for hybrid artistic events. She is currently a junior researcher at The Institute of Network Culture. She collaborated with activist groups, artists, and research institutes, investigating emotional landscapes and the potential of virtual environments for research and social change. She is a member of the activist collective UKRAiNATV (Kraków), THE VOID (Amsterdam), and holds an MA in Net Art from the Brera Academy of Fine Arts (Milan).