Contesting Capture Technology with Anti-Facial Recognition Masks

by Patricia de Vries

The journal-version, published in Platform: Journal can be found here.

It is far harder to kill a phantom than a reality – Virginia Woolf

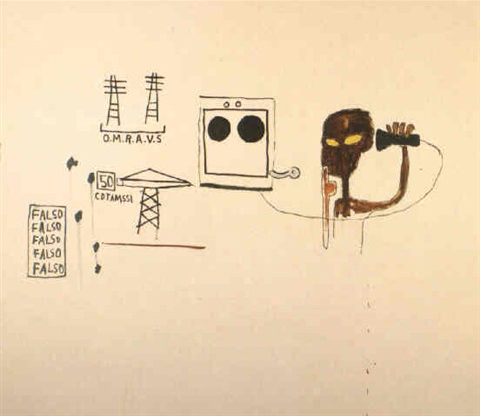

An “anti-facial recognition movement is on the rise,” writes Joseph Cox for The Kernel. It is a bit premature to call it a ‘movement,’ but indeed a growing group of artists and activists is criticizing the dissemination of what Philip Agre has called “capture technologies,” the computational acquisition of data as input into a database. The use of these technologies by state security programs, tech-giants and multinational corporations, has met with opposition and controversy. Zach Blas, Leo Selvaggio, Sterling Crispin and Adam Harvey are among a group of critics who have developed trickster-like, subversive anti-facial recognition masks that disrupt biometric and identification technologies. With their interventions these critics give shape to a developing counter-discourse on capture technology in what is often called an “Age of the Machine” and an increasingly “informational”, “datafied” and “softwarized” society with an “algorithmic culture.” What is being critiqued here? And what logic are they trying to break away from?

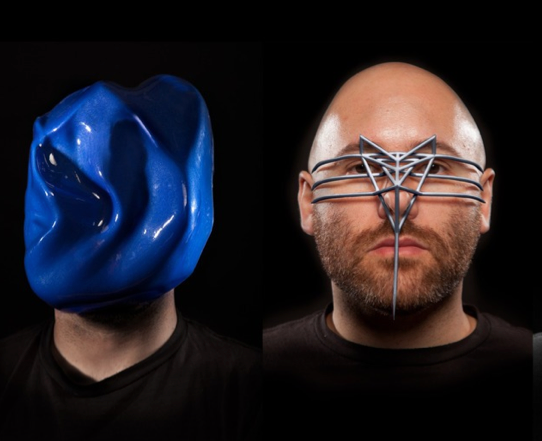

For his “URME Personal Surveillance Identity Prosthetic” the artist Leo Selvaggio developed wearable prosthetic masks of his face. Made from pigmented hard resin, using 3D printing technology and identity replacement technology, this mask is a 3D rendition of Selvaggio’s facial features. “Rather than hide from cameras,” Selvaggio explains, “simply give them a face other than your own to track without drawing attention to yourself in a crowd.” Selvaggio feels “an overwhelming urge to protect the public from this surveillance state” and offers his own identity as a “defense technology”.

Artist and scholar Zach Blas’ series of mask projects are designed on the one hand to visualize how identity recognition technology analyzes human faces, and to resist identity recognition technology by offering undetectable face masks. His series of 3-dimensional metal objects, ‘Face Cage,’ materializes the strong contrast between facial forms and biometric mathematical diagrams to visualize how identity recognition software reads a human face. His ‘Facial Weaponization Suite’ is a series of community workshops, geared at LGBT and minority groups, that produces amorphous masks that cannot be recognized by biometric software. The aim of these masks is to become “a faceless threat” by providing “opacity,” – a concept derived from the poet Édouard Glissant – a resistance to “informatic visibility”

Technologist and artist Adam Harvey’s CV Dazzle uses analogue camouflage to thwart face-detection technology. ‘Dazzle’ refers to a camouflage-patterned painting technique used in WWI on warships. The stripes and bold colors of this technique disrupt the outline of a ship and make it difficult to estimate a ship’s size, range and direction allegedly preventing an enemy from targeting it. Harvey’s CV (computer vision) Dazzle uses similar facial camouflage designs. He explains, “facial-recognition algorithms rely on the identification and spatial relationship of key facial features, like symmetry and tonal contours, one can block detection by creating an ‘anti-face’

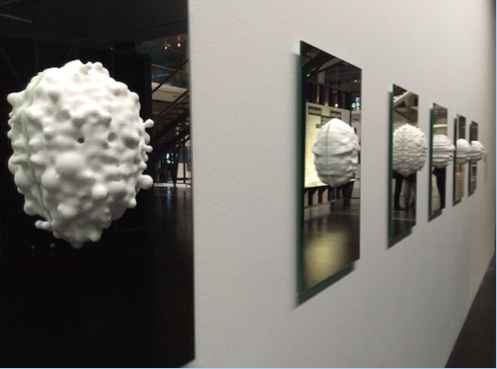

The Data-Masks of artist and technologist Sterling Crispin have been produced by reverse engineering facial recognition and detection algorithms. These algorithms were molded into 3D printed masks to visualize what robust models machine-learning algorithms recognize and detect as a face. Their goal, Crispin states, is “to show the machine what it’s looking for.” Data-Masks, he argues, are “animistic deities brought out of the algorithmic-spirit-world of the machine and into our material world, ready to tell us their secrets, or warn us of what’s to come.”

“The world is becoming increasingly surveilled,” Selvaggio says in the Indiegogo video he made to seek funding for his masks. “Virtual Shield, a database that has over 25K cameras in Chicago all networked into a single hub, comprises facial recognition software that can track you and pull up all of your corresponding data. …There isn’t that much privacy anymore.” According to Sterling Crispin “we live under the shadow of a totalitarian police state…” He claims we are “witnessing the rise of a Globally Networked Technological Organism” that will “exceed the human mind.” The part that is really human is lost in all this, ” he fears. For Harvey the problem is the “imbalance of power” between the surveiller and the surveilled. It is the ubiquitous and unregulated profiling and cataloguing aspect of these identification technologies that he considers a “threat to privacy.” Blas is concerned the global standards identification technology relies on “return us to the classist, racist, sexist scientific endeavors of the 19th century” and lead toward ‘Total Quantification’ annihilating “alterity.

Of course, technological monitoring and the control of people, communication and information as a form of governing has a long history. Information control is as old as the state itself. However, unfettered and unprecedented data and identification surveillance, storage and analytics conducted both by government agencies and private corporations, as disclosed by the Snowden-documents, has incited renewed concern about the implications of these technologies.

One way to look this criticism is that it fits within a long tradition in which the introduction of new technologies is met with opposition. While some cluck in anticipation and welcome new technologies as the harbingers of prosperity, on the other side there is handwringing, a fear that these developments will change humanity in a fundamental and negative way. Technologies of identification are no exception; hailed as the gold of the digital age that will fundamentally enrich humanity, and rejected as a tool of oppression eroding our civil liberties. Today’s debate, looked at it this way, is the umpteenth version of this age-old debate – old wine in new jars. However, this assumes all technology is essentially the same and it does not answer the question why identification technology is linked to visions of technological Frankensteins and Orwellian police states. Nor does it explain what logic drives these fears.

The Vision Metaphor

There seems to be a representation politics at work that engages with a limited series of metaphors to make sense capture technology. These metaphors give shape to how capture technology and the algorithmic and measurement-processes on which it runs are understood and critiqued. Metaphors are often meant to understand something unfamiliar by comparing it to something familiar. One of the more dominant metaphors of capture technology is seeing, or rather, vision. This metaphor affects popular understanding of capture technology; it affects how it comes to mind and occurs to people.

Critics of capture technology, too, describe the use of capture technology by governments and corporations through visual metaphors – spies, God-like eyes, Big Brothers, panopticons, specters are all around. Blas uses the metaphor of the panopticon: identity recognition technology, he argues, controls through an optical logic of making visible in order to police and criminalize populations all over the world. For Harvey “knowing somebody could be watching me…you always have a chaperone”, makes him ill at ease. Crispin writes about how we are “always already being seen, watched and analyzed” by what he calls an ‘Technological Other’, peering into our bodies, while Selvaggio compares capture technology to a form of “inspection.”

This metaphorical understanding brings attributes of visibility onto their ideas about how to approach this technology, and in turn informs how these critics engage counter capture technologies. The vision metaphor finds its counterpoint in invisibility. Blas, Harvey, Selvaggio and Crispin maintain that one must undermine capture technology by becoming imperceptible. This invisibility is not sought in incorporeality or hiding, or becoming transparent, but in becoming undetectable, unidentifiable to identity recognition technology by concealing your face.

Selvaggio claims his masks work as decoy by having his face captured instead of your own. His masks “are best activated by a group of people in public space, like activists or protestors.” Crispin, too, likes to cater to the supposed needs of protestors. He writes about his Data-Masks that they are “intended for use in acts of protest and civil disobedience,” and are themselves “an act of political protest” by means of “giving form to an otherwise invisible network of control.” Blas sees his masks as a tool in the tradition of collective protest movements like Anonymous, the Zapatistas and Pussy Riot. “Facelessness and becoming imperceptible are serious threats to the state and to capitalism,” Blas claims in a video Communiqué. “Masks produce their own autonomous visibilities” and make revolt possible, Blas says in an interview with The Kernel. Selvaggio asserts his masks create a “safe space” and a “statement on the right to assert yourself in public space.” Crispin writes of his Data-Masks that they “empower, rather than enslave,” and “address the human as human.” Harvey’s CV Dazzle claims to offer “more control over your privacy” by “protecting your data.” Though they are quick to mention that in some states and countries it is illegal to wear masks and that one should check local laws before using their devices.

As Kathryn Schulz writes: “The dream of invisibility is not about attaining power but escaping it.” From what puissance are they trying to escape? Selvaggio claims the omnipresence of surveillance technologies affects our relationship to identity. Identity, he claims has come to be thought of as data: highly manipulable, editable, and corruptible.” According to Blas capture technologies “produce a conception of the human as that which is fully measurable, quantifiable and knowable.” Identity is “reduced to disembodied aggregates of data.” Crispin writes that these networked systems “see human beings as abstract things, patterns, and numbers, not as individual people whose lives matter.” They define the human as a what, not as a who, he asserts.

It is here where their metaphorical understanding of identification technology as a way of seeing, and being visible, clouds their aims. The primary aim of these masked interventions is to repudiate the omnipresence of surveillance identification technology and its controlling and reductionist effects. They oppose these supposed effects by providing ‘autonomous zones,’ safe spaces that are meant to enable revolt.

To an important degree these works are trickster reversals, mirror opposites, that make a stand about how identification technologies ‘work’. Blas’ Facial Weaponization series turn the logic of identification technologies around by making our faces undetectable blobs “producing non-existence.” CV Dazzle defies detection by way of solarization, creating a negative form. URME Prosthetics work by turning an individual face into a collective, while Crispin’s Data-Masks “hold a mirror up to the all-seeing eye of the digital-panopticon.”

In various ways these disguises express their critique of capture technology by way of negation. They form its logical opposite. They are non-human, amorph, unrecognizable, unidentifiable and undetectable. This approach is in itself reductive. Reductionism in all its forms begins with dualisms: human/non-human, power/powerless, quantitative/qualitative, existence/non-existence, individual/collective, amorphous/ geometric, and digital/analogue.

Binaries result in static contrasts and negations. Negations boil down into oppositions, polarizations, and antagonisms – hence the references by these critics to WWI dazzle strategies, weapons, revolt, and technological Frankensteins. This dualist approach leads to what Richard Bernstein has identified as a “Cartesian anxiety,” the “grand Either/Or.” Either you are visible and powerless, or invisible and powerful. This binary logic is problematic as it implicitly assumes that resistance to identity recognition technology results from the interplay between opposites. It is also problematic because it reifies a logical law; it treats a metaphorical abstraction as if it is a concrete thing. What is more, opposition in terms of reversal, a binary approach, keeps these critics closely tied to the logic they are meaning to break away from — albeit in a negative form.

Arguably, Blas expresses concern about how capture technology forces normative categories upon minorities. He explains that his masks represent a desire to cultivate “ways of living otherwise.” “Alterity,” he argues “exists within the cracks and fissures of quantification.” You could argue that his Facial Weaponization series vie for heterogeneity, opacity and non-normative subjectivity, and they do, but they do so in opposition to a homogenous, normalizing, technological “Apparatus” – yet another dualism. His series of masks are purportedly about what lies outside of templates of human identity and activity, about the reductionism of quantification, and a desire to “let exist as such that which is immeasurable, unidentifiable,” but these “autonomous visibilities”, as he calls them, are posited in firm opposition to ‘the’ technological surveillance state; a gigantic unifier, as the primary ‘other’ with which we interact. So, though clamoring for the immeasurability and alterity of people, technology is represented as a monolith, as a Technological Enemy-Other.

Albeit in different ways, neither of these masked interventions go beyond contradicting the dominant assumptions about identity recognition technology. Their respective projects do not challenge the being, the underlying logic that spawns these identification technologies. That is, they reflect on a changed socio-technical context, but they remain within an optical logic.

What is more, this Other is threatening an idealized, and highly privileged, conception of the Self. A self that is assumed to be autonomous, self-assertive, endowed with humanitarian values, and living in privacy – grandiose assumptions that are not explained nor defined. This echoes both a modernist obsession with origin(al)s, as well as, as Hans Harbers describes, the endemic Romantic narrative of despair. “It is the story of being overrun by a technological juggernaut, which is guided only by instrumental values…”

I/Eye

Contrary to their appearance, these masked interventions are more situated in the field of epistemology than in that of activism, engineering or aesthetics. They are shaped by the Western epistemological paradigm based on the centralization of vision and the identification of vision and knowledge: to see is to know. These masked interventions represent the encounter between the human eye and the alleged mechanical “eye” of identity recognition technology. However, identity recognition software is an interface, and the data it spits out are numerical representations; they are not, as Donald Preziosi aptly puts it, “re-presences,” they do not “make present again.” Data is not found, captured, or taken from nature, but made. Recognition technology works on mathematical instructions, and math, like it or not, does not exist in a socio-political vacuum. This is to say identity recognition systems do not “see.” What “looks at you” is not an technological ‘Eye’, what “looks” at you is the ‘I’ of the human consciousness that develops these technologies and charges them with anthropocentric significance and assumptions, i.e. highly advanced, networked technology, combining all sorts of personal information into a data-hub supposedly taps deeply into our Being and threatens Humanity and humanitarian values.

The vision metaphor limits a critical understanding on how technology affects us. It reifies a logic it claims to critique verging on metaphysical assumptions and self-idealizations. As Stanley Cavell writes “our philosophical grasp of the world fails to reach beyond our taking and holding views of it.” The metaphor “obscures” and simplifies an entire socio-technical infrastructure of people and interfaces that calculate, read, create, interpret, valuate, process, vet, sift through, pass on and manipulate data. And the vision metaphor, too, obscures the role of faith in data – the Believe we have in it – as well as how sciences also rely on intuition, revelation and inspiration.

One could object, of course, that these projects make present what otherwise remains invisible. Data-Masks could be read as to ‘actualize’ the virtual, showing the rudimental oval shapes that pass for a human face online. You could argue these “deities”, as Crispin calls them, represent the (pan)optical logic as a belief in ghosts. And, indeed, the “faith” in Big Data might very well be the unicorn of the 21st century. Still, though, these Data-Masks rely on a dichotomy between human/machine, virtual /real identities, and on an optical/actual logic.

Over and against a binary thinking of demarcations, isolated domains and resistance as opposition, pragmatism posits a thinking in terms of relations. Moving away from totalizing dualist narratives and towards a pragmatist turn, we could come to reimagine identity recognition technology not as an object for our eyes, but as a relationship between living organisms and things. In the footsteps of William James, Latour’s actor-network-theory (ANT) understands technologies as actors in a network interacting with and co-constituting the social. Of central importance here is the mutual constitution of society, technology and science. From a relational perspective, identity recognition technology ‘acts’, it does something, “it makes a difference” as Latour argues. Society and technology are internally related and mutually constituted.

Such an understanding dissolves the dead-end road of the dichotomy between bodies and technologies and exposes a myriad of actors, actions, powers and counter-powers, things and people that are all part of the spectrum of capture technology. Seen this way, capture technology consists of a manifold of ambiguous, contradictory and competitive actors ranging from air strainers, crypto-anarchists, rubber tubes, data brokers, Fitbits, politicians, programmers, borders, security policy papers, fiber optics, Snowden-documents, data-mining software, Singularity-thinkers, mathematicians, code, data-farms, coolers, water, clunky CCTV boxes, William Binney, islamophobes, dating apps, smart coffee machines, hackers, and also hard disk failures, information overload, glitches, overheated processors, errors, malfunctions, 404s and the bottom of the ocean floor – and, importantly, also of these masked interventions. All are actors, or as Latour calls them, ‘actants’.

Giving constitutional significance to both humans and things invalidates dualisms, but what is more it does away with the anthropocentrism inherent to visual metaphors. It would be hyperbolic to think this perspective emanates to relativism – we should not fall victim to the grand Either/Or. A relational approach, Bernstein has showed, does not preclude acting on strong convictions, but it demands and open view. These masks ‘do’ something; they have effect. They do not engender invisible power, nor help end capitalism, or safeguard “privacy” and “autonomy”. But they are seen, written about, critiqued, put on display at exhibitions. They form a kind of counter-power, constitutive parts of a network consisting of a plethora of tools, concepts and works of art ranging from dystopian novels, movies, browser extensions for anonymous web search, pleas for a right to disappear, that together constitute a counter-discursive network of capture technology – and that perhaps could snowball into a movement.

Looking at identity technology through a relational “lens” makes it more complex, multiform, ambiguous, but also gives us a lot more to work with opening pathways to intersectional (social, political, racial, legal etc.) forms of critique. We are in need of movements that resist the temptations of an binary universe. If we can think and act without this banister, and abort the vision metaphor, we may then eventually take steps toward undermining some of the actors on the capture technology spectrum, amongst which are nationalist notions soil, economic insecurity, racial bias and islamophobic rhetoric.