An extended version of this article was first published in Canon Magazine.

The Sputnik Project

The term “archive” evokes a dusky place full of photographs, shelves lined with wrinkled pages, and smudged glass encasing cluttered artifacts. The exhibition space of Sputnik, part of the retrospective “De Facto. Joan Fontcuberta 1982 – 2008” (Barcelona, 2008), does much to reinforce this view. With Sputnik, Fontcuberta presents an ordered collection of photographs, texts, documents and other archival material. Entering the black-walled, dimly lit exhibition space, the objects and artifacts displayed are diverse: black and white photographs; showcases with newspaper articles; books documenting the Space Race between the USSR and the United States published by the Sputnik Foundation; many graphic records, radiographs and maps; electro-optical photographs and geophysical data that document the course of the space shuttle Soyuz 2 minute-by-minute, and a television shows a rerun of an episode of the Spanish TV show Cuarto Milenio.

A text on the exhibition wall explains: Back at the height of the Space Race, when the United States and the USSR were working against the clock to land on the moon, the political pressures trumped concern about safety and the space program began to claim its toll of victims. On October 25, 1968, Soyuz 2 was launched from the Baikunur cosmodrome, with Pilot- Cosmonaut Colonel Ivan Istochnikov and the dog Kloka on board. For reasons that have never been made clear, the cosmonaut disappeared in the course of the mission. Istochnikov and Kloka had successfully carried out a spacewalk together, filmed by the camera’s on the outside of the ship, but because of a malfunction the crucial manoeuvre of docking with Soyuz 3 had to be aborted. The twin spacecraft drifted apart and lost contact. When Soyuz 3 managed to return to the docking position a few hours later the impact of a small meteorite was visible on the hull of Soyuz 2 and Istochnikov had vanished without a trace.

Strolling through the aisles, we get an impression of what appears to be the result of a years-long research project. Visitors can leaf through a textbook that describes the course of the Sputnik-project from its start at an auction of Russian space material at Sotheby’s in New York. Furthermore, next to texts that inform the reader about the cultural and historical background against which the Space Race took place, various black and white pictures are displayed that reconstruct the childhood, family life, career and space journey of the cosmonaut Ivan Istochnikov. Consider the images below, shown on the wall of the exhibition space. The first photograph [1], which looks like it came from a family photo album, shows Ivan Istochnikov in what appears to be a merry-go-round. The second photograph [2] shows, as we learn from the caption, Ivan at an older age when he graduated from the Aviatsioni Technikum. Another photograph [3] shows the bridal couple Ivan and Irina. The following photographs [4, 5] document Ivan Istochnikov’s achievements in his career as a cosmonaut.

[4] Captain Istochnikov is given a royal welcome with the “handkerchief of pioneers” in Moscow, 1977

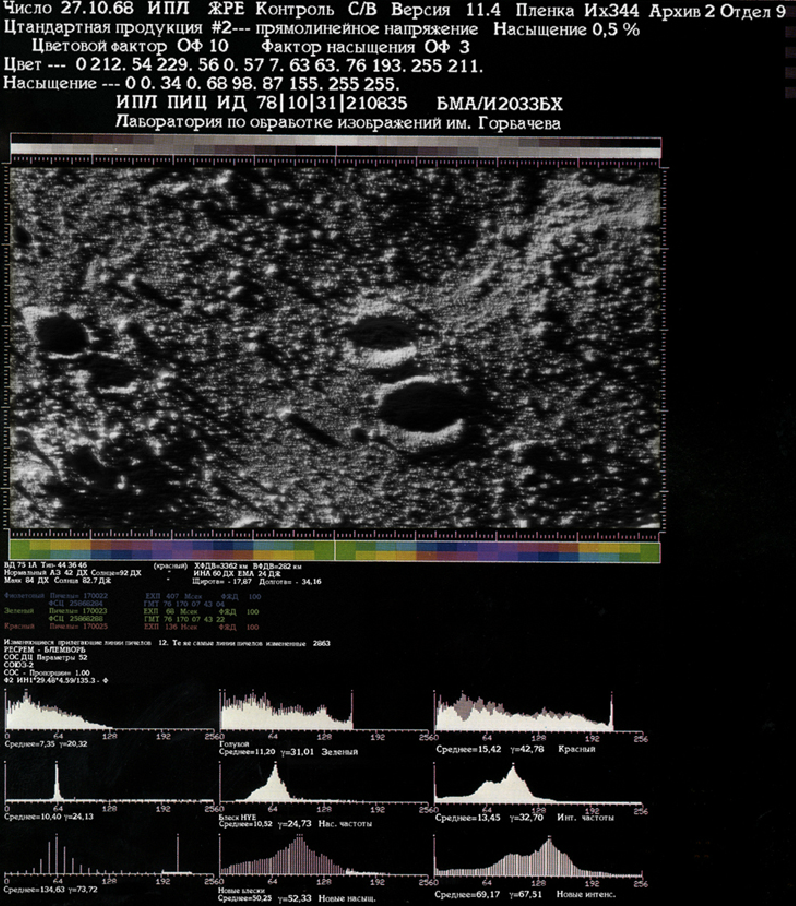

[6] Left: Original photograph sold at Sotheby’s in New York on December 11, 1993. It is dated December 7, 1967 and signed by, from left to right, Leonov, Nikolayev, Istochnikov, Rozhdestvensky, Beregovoi and Shatalov. Right: The same image, manipulated, as it was published in the encyclopedia Bound for the Stars by Boris Romanenko. [fontcuberta.com]

The Archive as Aesthetics & Epistemic

Two photographs stand out [6], one of which was bought at the Sotheby’s auction. The photo on the left, shows Istochnikov together with five men at an official occasion. The second photograph on the right shows the exact same image; however, in this picture Istochnikov is missing.

A text on the wall continues:

Regardless of whether it was sabotage or an accident, the Soviet authorities were clear about not wanting to admit another fiasco and they designed a Machiavellian explanation: they announced that the Soyuz 2 had been an automatic, unmanned flight. To avoid contradictory voices his family was confined, his colleagues were blackmailed, the archives were doctored and photographs retouched. It was only much later, with Glasnost and the subsequent fall of the Communist regime, that independent researchers of the Sputnik Foundation and Istochnikov’s relatives were able to unravel the fantastic fabrication and reinstate the missing man. The secret documents relating to the case were [de]classified and a wealth of images of Istochnikov’s day-to-day life, his training and his mission came to light, making it possible to reconstruct a remarkable episode that continues to defy belief even today. (Sputnik Exhibition Text).

With Sputnik, Fontcuberta presents an ordered collection of photographs, texts, documents and other archival material. Sputnik adopts an archival structure: an ordered presentation of photographic material, data and documents that serve to prove something. In this case it provides information about the life of Ivan Istochnikov. The photographs displayed might be described as ‘documentary’, given their straightforward style, their lack of aesthetic effects, their strict framing and their neutral, descriptive captions.

Fontcuberta never contends that his Sputnik installation is an archive, nor its contents documents. Nevertheless, the Sputnik documents were taken as evidence of the remarkable life of Istochnikov by the Spanish journalist and TV-moderator Iker Jeménez. On June 11, 2006, Jeménez devoted part of an episode of the Spanish television show Cuarto Milenio to the disappearance of Istochnikov. However, and in spite of the detailed documentation, there never was a cosmonaut named Ivan Istochnikov who disappeared in space. The Sputnik material may seem real, but it is in fact a combination of manipulated and real documents and photographs, collected and fabricated by the artist. It is even the artist himself who appears in the photographs as Ivan Istochnikov. Istochnikov comes into existence through the “factual” presentation of documents, data and photographic “evidence” from different sources: journalistic, military, geological and personal.

With Sputnik Fontcuberta confronts us with questions about the truth and veracity of what we consider ‘documents’. What is more, Sputnik challenges the prevailing trust in the authority of the historical archive. Fontcuberta made an artwork that espouses the form of the archive to challenge the alleged objective nature of archival material. If photographs and documents presented in an ‘archival mode’, can produce credible “evidence” of an event that never happened, then the notion of the ‘document as evidence’ is put in doubt. As Fontcuberta argues in his book Beso de Judas: “Because we should have asked ourselves: Evidence of what? Perhaps evidence only of its own ambiguity. What remains, then, of the document?”

It is not coincidental that Fontcuberta uses archival form. What do we mean, then, when we speak of archives? If we consult the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) and the New Oxford English Dictionary (NOED) we read in the former “archive: (from Gk. ta arkheia “public records”) 1. a place in which public records or other important historic documents are kept. 2. A historical record or document so preserved” (OED). The New Oxford English Dictionary writes “1. a collection of historical documents or records providing information about a place, institution, or group of people. 2. the place where such documents or records are kept” (NOED). From these definitions we can derive two characteristics: first, the reference to the notion of a document. Archives consist of historical documents: they are, in fact, a body of documents to be preserved. Second, archives are the result of human activity. The definition of the archive outlined here leads us to a second definition, that of the document.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) a document “(from L. documentum “example, proof, lesson”, from L. docere “teach” from Fr. document “lesson, written evidence”) is 1. an instruction, a piece of instruction, a lesson; an admonition, a warning. 2. That which serves to show, point out, or prove something; evidence, proof. 3. Something written, inscribed, etc., which furnishes evidence or information upon any subject, as a manuscript, title-deed, tomb-stone, coin, picture, etc” (OED). The NOED gives the following definition: “a piece of written, printed, or electronic matter that provides information or evidence or that serves as an official record.” In general terms documents are objects that serve the purposes of education, record or providing documentary proof or evidence.

It is Fontcuberta’s deliberate strategy to make an artwork that espouses the form of the archive to challenge the alleged objective nature of the document as truthful material. In the art world the concept of “the archive” has also proven to be an important trend. Art critic Hal Foster writes “archival artists seek to make historical information, often lost or displaced, physically present”. The work resulting from this “archival impulse,” as he Foster it, is archival “since it not only draws on informal archives but produces them as well”. Contemporary artists such as Douglas Gordon, Péter Forgács, Andrei Ujica and Harun Farocki are only some examples. Many “archival artists” adopt the form of an archive to re-collect and contradict official readings of an event. In his film archive Meanwhile Somewhere… 1940-1943 (1994) Peter Forgács, for example, collects amateur videos and clandestine amateur shots as “evidence [of] private aspects of the war,” stating in an interview that he believes that amateur images and home movies of individuals are more “spontaneous” and “subconscious”. In their archival film Videograms of a Revolution (1993) Harun Farocki and Andrei Ujica also use amateur and professional archival video footage to rework a view on the Romanian Revolution of December 1990.

Although they may vary in the perspective on a historical event, Fontcuberta – unlike these artists – does not have the illusion that amateur counter-archives are of a different quality than official ones. The distrust of official archives expressed by these artists in creating an oppositional counter-archive stands in contrast to Fontcuberta’s mistrust of all archives. Instead, Sputnik forms a meta-archival approach that exposes and rejects the very logic of an archive as “the foundation of factual knowledge”. What is more, Fontcuberta utilizes “amateur images” as a deliberate strategy to give these images the credibility of pieces of evidence or documentation. As Stella Bruzi has showed in The Event: Archive and Newsreel, it is “the lack of aesthetics” that give these photos their “truth-effects”. The family photos of Istochnikov seem “spontaneous,” “authentic” and “innocent” due to their “home made” quality. These family photos seem all the more “real” since they “document trivial, banal events”, Bruzi explains. Banal facts of the life of a Russian cosmonaut. However, what is here understood as factual is, in actual fact, fiction. Fontcuberta created a reality implying that the truth we are willing to accept can be produced.

Another factor that conditions the effect of truthfulness relates to the shaky opposition between word and image. What happens when the texts and the captions accompanying the photographs are removed? Lacking any type of explanatory caption, the observer of these photographs would find in them “documentary” photographs of trivial happenings in the life of an unknown individual. What one is left with, due to the absence of any contextualization and narrativization, is the banality of different scenes out of the life of a stranger. Without contextualization and narrativization we are left with what Flusser would call “fragments of enunciations”.

The Archival Document as a Judas Kiss

We have known this already for a long time. The question is why do we act against our best judgment? Fontcuberta weaves together conceptions of documentary photography and the alleged objectivity of archival material in an artwork that challenges the consensus of documentary material as valid pieces of non-fiction. This idea is, however, not new. In the 1960s, in the context of linguistic and semiotic studies, the conception of a transparent medium was already subject to attack. As the American philosopher Stanley Cavell argues, “our philosophical grasp of the world fails to reach beyond our taking and holding views of it.” Our notion of reality is always fractured, fragmented and ungraspable. However, the effect Sputnik has on its viewers derives partly from the enduring belief in the existence of unmediated and objective documents. This is not to argue that all mediated documents are manipulative pieces of fiction. It is to argue that there is only so much any document can reveal.

Sputnik’s message has been part of our intellectual register since the last century. And yet, Sputnik exposes something that forced me to work through the art work and draw this conclusion once more. Something makes us persist in believing in the veracity of documents, which causes us to be fooled and take for non-fiction what is in fact fiction. That “something” is the same age-old and persistent desire of seeing what we believe with which we fool ourselves. We see things that accord with our world-view and neglect information that may contradict it. We see the Sputnik-documents as the evidence of the erasure of Istochnikov when we believe that he could be erased, and because we believe archival material to be evidencing historical events. What Sputnik shows is the paradox that we do not necessarily believe something when we see it. Rather it reveals that we see something when we believe it. The historical context of Soviet practices of erasure and assumptions about Russia together with the seemingly “unmediated” form in which the information about Istochnikov is presented, make us believe there was a cosmonaut named Istochnikov who disappeared in space. Consequently, we see the photos and documents displayed as evidence of his existence.

“What remains of the document?” Fontcuberta asks.Although we know we cannot know everything, that we cannot grasp the Real, we do not act on this knowledge. What remains of the document is that the deceiving appearance of documents-as-objective is kept up in the archive.

It may be hard to live without a sense that there is a real we can know or get to, but we may find comfort in the words of the Italian painter Giorgio DeChirico: “Et quid amabo nisi quod aenigma est?”.