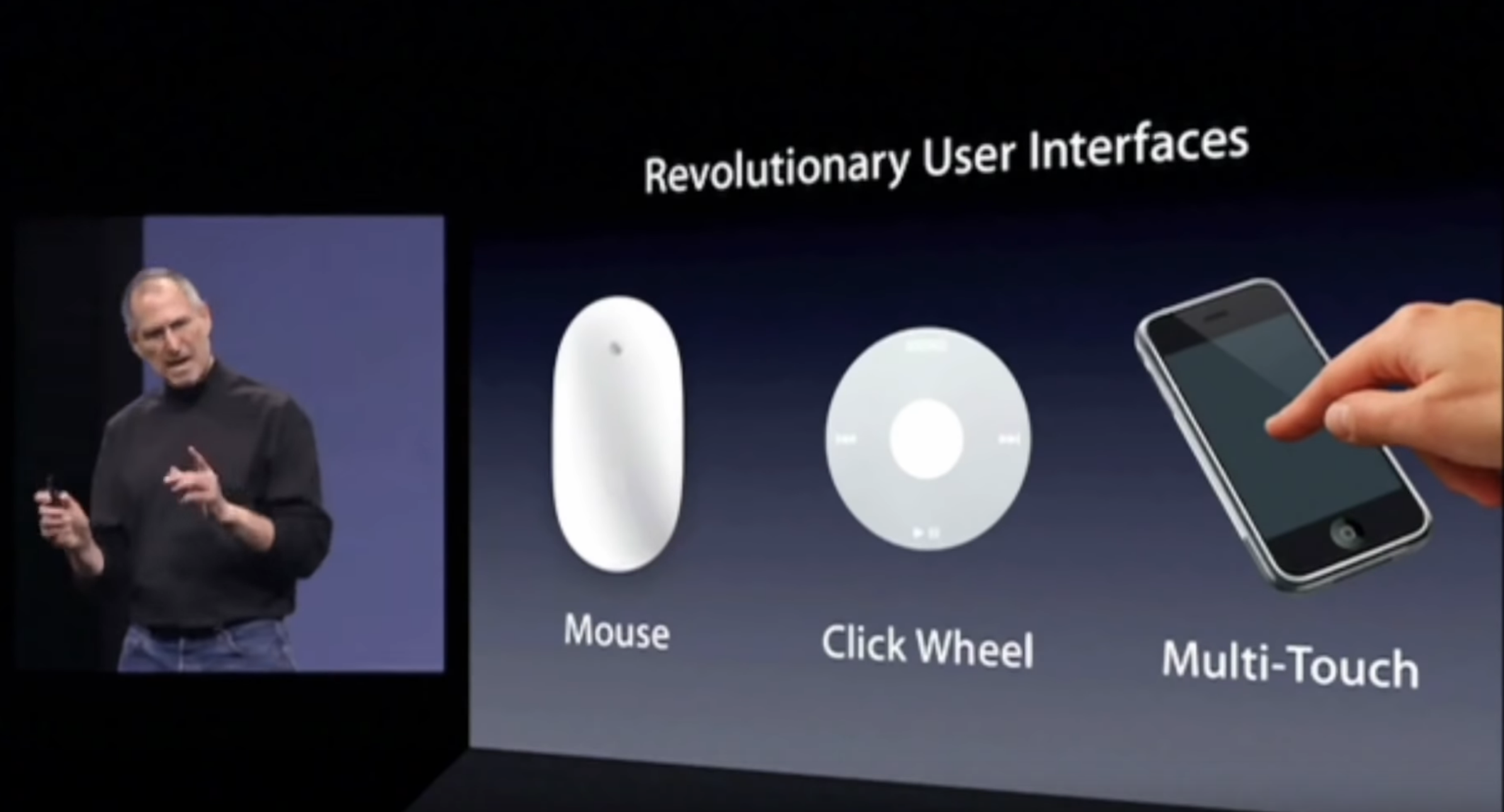

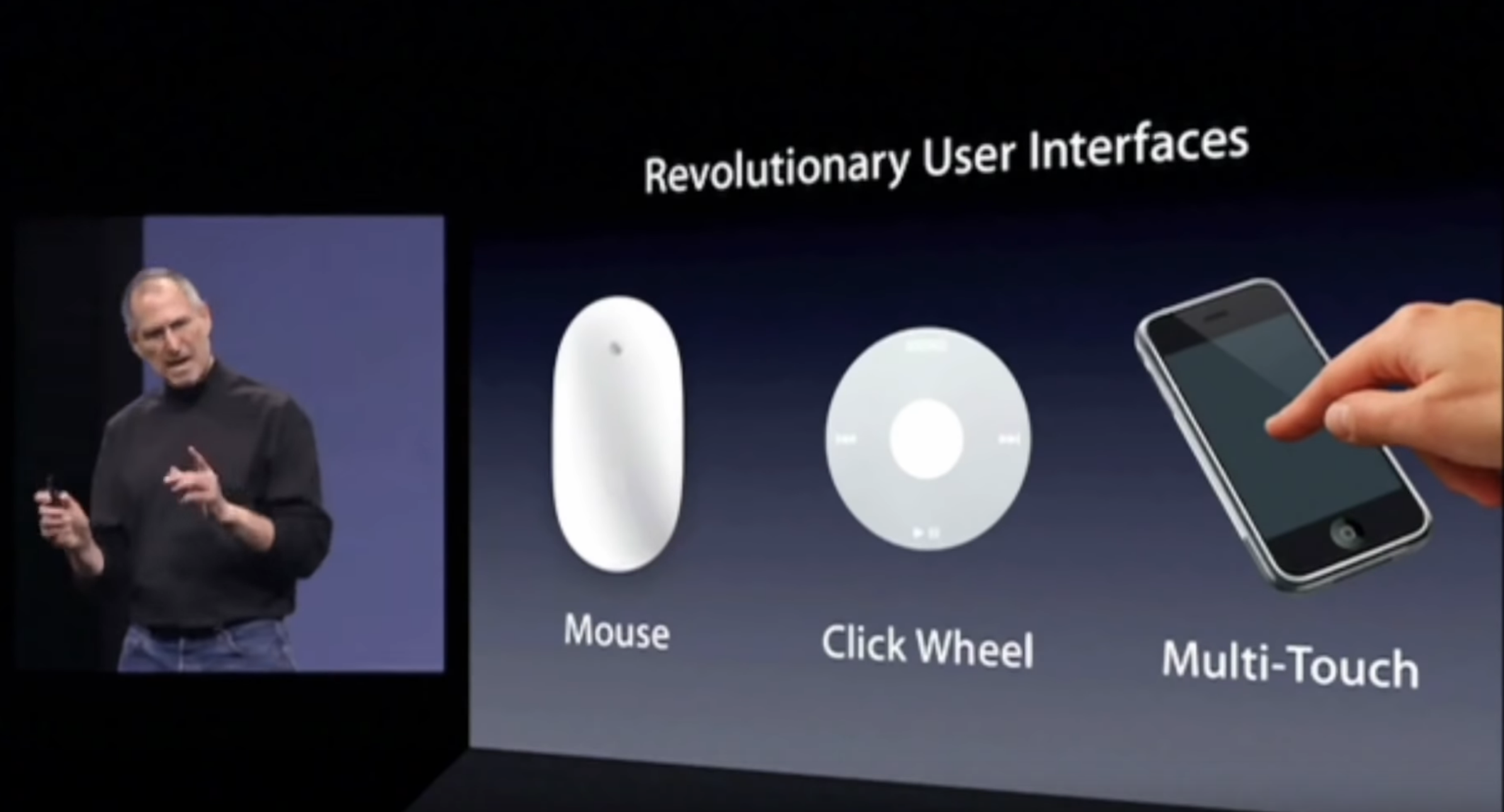

Apple’s “revolutionary user interfaces”

In a previous post, I hypothesized that the evolution of web user interfaces can be understood as their progressive automation which, following the paradigm of industrialization, produces in turn a proletarization of the user. In this post I propose a tentative chronology of technical inventions as well as future forecasts, formulations of trends, and public admonishments that have contributed to and engaged with such transformation. The term proletarization is inspired by French philosopher Bernard Stiegler. I do not use it in an accusatory or moralistic sense; by that I intend to simply point out that, by means of semi-automation first (infinite scroll), and full automation then (playlist, stories, etc.), the user is turned into a “hand” first and then into a machine operator, someone who supervises the machine pseudo-autonomous flow and regulates its modulations. Following Simondon, the machine replaces the tool-equipped individual (the worker).

There are four main intertwined threads in this chronology: the emergence of web apps, the invention of the infinite scroll, the appearance of syndication and aggregation, the introduction of smartphones and thus the swipe gesture.

As I’m sure I’m missing or misunderstanding some aspects of it, comments are very welcome. There is also a loong Mastodon thread about this. Let us begin.

Read the rest