On AIGA’s Eye on Design blog there is a new series called Design + Money. Its first article, design writer Perrin Drumm raises the vexed question of unpaid work. According to Drumm, one shouldn’t always get paid for their work. The apology of some specific instances of upaid labor is backed by Paula Scher, the graphic design giant portrayed in the first season of Abstract, Netflix’s new docuseries on design. Scher’s main argument is that unpaid gigs offer "total creative control over a project".

Scher is alarmed by the fact that the designers "don’t use the opportunity to grow their work where they have control, which will ultimately lead them to do better as designers later." In this perspective, doing work for free becomes "a total power move". Pro bono projects give designers the opportunity to set their rules, to decide what and how it should be done. Last but not least, they are finally free –both as in freedom and in beer– from having to "collaborate" with the client. The presumably excellent results of such approach will then populate a growing portfolio of impeccable works.

Unfortunately, once such high standards are set, it isn’t easy to go back to the drudgery of classic professional relationships. Many of my friends, after having built an enviable portfolio while studying, struggle to work in the "real world" since they got used to such limitless freedom. They grow frustrated since they realize that design is at best an art of compromise, at worst a counselling activity. Slick designs produced in vitro become representative of the profession and, since they are hardly repeatable as paid jobs, the mundane, messy richness of social life is in turn despised.

While pro bono projects are endorsed, speculative work, "the work done for free in the hope of getting paid for it", is here heavily demonized ("Don’t do this. Ever"). According to AIGA, the problem with spec work is that it devaluates the design profession and undermines the quality of the outcomes. The association even provides a customizable letter to politely turn down spec commissions. Furthermore, designer Jessica Hische offers a useful flowchart to decide whether one should take an unpaid gig or not.

These tools, made with the best of intentions, seems a bit out of reality. Unemployment in the graphic design field is a concrete threat for a growing number of professionals. Moreover, performing an exploitative activity is more socially acceptable than not having any kind of occupation. "The only thing worse than being exploited is not being exploited", some people say.

How can you blame an aspiring designer if they take an exploitative gig with the hope of getting a proper job or commission as a reward? After all, it is a logical form of investment: in an increasingly competitive market, the ones who survive are those who have more economic stamina. We clearly see this happening in the context of unpaid internships: an unpaid internship is clearly a form of spec work, or hope labor, a luxury that is not affordable by everyone. An unpaid internship is a lottery where the prize is a contract. No need of an MA in Economics to understand how this dynamic contributes to the widening of inequality. Thus, the somehow moralistic commandment to reject spec work seems more a way to protect those who are already settled in their professional position than a means of helping the ones who aspire to that.

When Paula Scher’s encounters a promising brief she says ‘I don’t want the fee. I want to do what I want.’ Scher appears obsessed with ‘control’, in the short article the word appears six times. I can’t avoid to find the abuse of the term ironic, since what characterizes my generation, the so-called Millennials, is exactly the total lack of control, be that of our careers, of our future, even of our own thoughts and feelings. Increasingly indebted, underemployed and depressed, millennials insist that their real job is the one that they do at night or in the weekends, after a shift at the cafè. For many of them, the whole design practice coincides with spec work.

"When you’re on your own you’re operating more as an innovator and a creator”, Paula Scher argues, without realizing how these words plump the collective self-delusion of innovation, disruption and empowerment. We shoudn’t forget that this myth of agency and autonomy is often complemented by all-nighters in front of the computer and the sacrification of a whole array of pleasures that aren’t related to work. Is there pleasure outside of work anyway? Who even remember anymore? During a recent conference, Irma Boom, a Dutch graphic design superstar, insisted on the fact that she works all the time, because that’s what she wants, that’s the life she has chosen. While Boom has every right to invest all her time in work, these kind of statements contribute to the glamorization of workaholism. As a consequence, workaholism becomes more than a regime, it turns into a status symbol.

Designers should be wary of Paula Scher’s perspective, not because they know better, or because her opinion isn’t valuable, but for a simple statistical reason: only a tiny minority of them will get even close to her professional status. Paula Scher’s bold claims are yet another version of our society’s most obsessive refrain: "work hard and you will make it". We should know by now that, in many cases, this is a scam. That said, we shouldn’t forget that doing things for free can actually be fun and rewarding, it might even have positive effects on the anxiety provoked by precarious conditions. Even if it is for a good cause, we should resist the urge to interpret any kind of social interaction as an economic exchange. After all, the financial mindset is exactly the veil to break in order to live a richer life.

Paula Sher is upset by "the lack of understanding that this is about power". I agree on this matter: we must frame the issue of unpaid work within a broader understanding of structural power, not purely individual one. Who has the power to perform unpaid work? Who is not granted such possibility? Why? One of my teachers, a designer celebrated worldwide, once told me that whatever the conditions in which a project was developed, he took full responsibility for the quality of the outcomes. It’s time to subvert this ethos. When control is restricted to one’s little pro bono project, when there is no truly free choice, the conditions in which we work shouldn’t be concealed, instead they should be communicated, visualized, designed. The question is not why and when it’s worth to work for free but what allows or prevents designers to do so. Perhaps, this is a pro-bono project worth our free time.

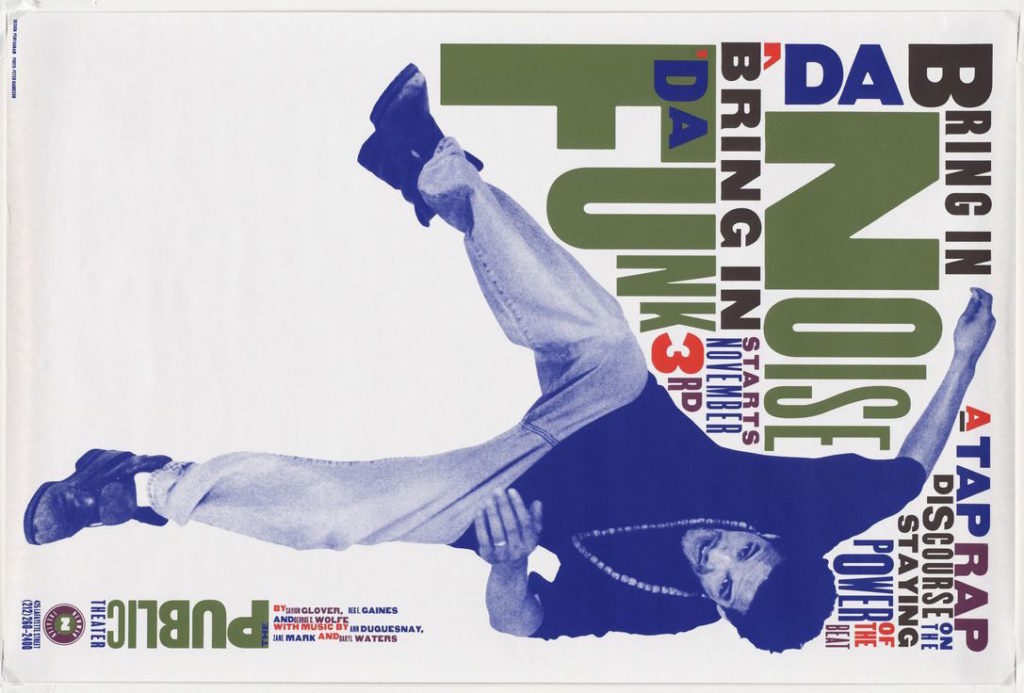

Photo: Paula Scher. Bring in ‘Da Noise Bring in ‘Da Funk. 1995. Turned 90 degrees.

Also published on Medium.