By Rachel O’Reilly

Francesco Franco’s research at Birkbeck College London focuses on art, technology and politics at the Venice Biennale between 1966 and 1986. Venice is the oldest festival of contemporary art worldwide, and an interesting case study for many of the changes occurring in Europe during this time. From the early 60s the organisation was plagued by shifting demands for democratization of art and the expansion and dissolution of categories. Action on these issues, Franco argued, was somewhat muted in 1966 by the space given to kinetic work including that of Julio le Parc who contentiously won the painting prize. Demonstrations at the 68 Milan Triennale and the June 68 Venice Biennale by students and prominent intellectuals massively impacted; the charter abandoned artwork prizes and medium specific categories as well as the Grand Prix, deemed irrelevant to contemporary practice. (The Golden Lion was instated in 1994).

Franco suggests that the presence of computer-based works in 1970 under the banner of ‘experimentation’ must be understood as a means to engage audiences in this context. The main pavilion uniquely housed a display of actual documentation proposals for the experimental exhibition. Focus was given to the active and conscious spectator; to art without categories; and to computer-based experimentation (Russian constructivists, Comptuer Technique Group, “the new technique” movement, Herbert W. Franke Aurro Lecci, Freider Nake). The Nuremburg Biennale in 69 precursored the inclusion of computer work in the Venice show (Max Bil, Josef Albers, Georg Nees). Franco considers the “new tendencies” group and exhibition in Zagreb was as much concerned with a burgeoning computer aesthetic as it was with direct political disillusionment with the Venice Biennale.

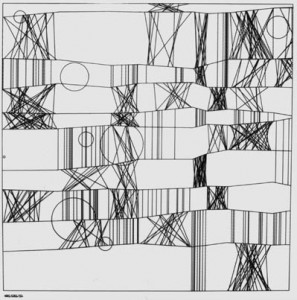

Nake image, Frieder Nake,”Klee”

According to Franco, computer art at Venice was not necessarily a “radical gesture” but an answer (recuperation) to the instability of the institution, and an unusual case in Biennale history. The computer technique group had already commenced a timely critique of its own relevance (see “Goodbye Computer art” letter, 1970).

‘Radical acts’ remained a floating signifier in this talk. In question time Franco suggested Krzysztof Wodiczko “Guests” work in 2009 was a lone recent example. It would have been great to match this rigorous institutional research with closer readings of contested works, and more transparent political-aesthetic criteria. An audience member queried the positivity of achievement rendered for kinetic work (as radical today) over computer media-based work (lost to corporate commerce and the art market etc) in the history presented, essentially pointing to the trouble with post-media or post-category art history, criticism, curation.

Krzysztof Wodiczko “Guests” 2009, Venice Biennale