On Tuesday June 23 the Facebook Liberation Army, a collaboration of the Institute of Network Cultures, Waag Society and the Stadsschouwburg Amsterdam, organized the Facebook Farewell Party.

Het Nationale Toneel (in the guise of Anniek Pheifer, Mark Rietman and Jappe Claes) gave theatrical shape to the three divisions of the Facebook Liberation Army: the Underground, the Resistance and the Refugees.

The lecture program in the Main Hall was followed by an extensive break out program in collaboration with Worm, Hackers & Designers, Greenhost and Submarine. In the salons and lobbies of the Stadsschouwburg you could tinker hands-on in DIY workshops, learn how to better protect your online privacy, or dance to the liberating tunes of DJ POP CTRL. You could join a Social Media Rehab Clinic, or a workshop on how to build a network within Facebook that allows you to operate anonymously. An analogue version of Facebook, where you could write on the wall and make new friends, was another attraction. Also on display was an installation that encrypts your messages on social media using … your heartbeat! Eventually everyone went home with a Facebook Survival Kit.

A report from the trenches, by bloggers Katía Truijen, Tijmen Schep and Christine van Spankeren, with photos by Charlotte de Gier.

Escaping the Farm

A report from Aral Balkans lecture by Katía Truijen.

Aral Balkan is a designer & social entrepreneur, creating independent technologies in order to protect our fundamental freedoms. During his talk at the Facebook Farewell Party, Balkan emphasized the need for stronger democracy and alternative social media.

In this era of the Anthropocene, Balkan argues, we are confronted with systemic inequality. The 85 richest people of the world have the same amount of money as the 3.5 billion poorest. In order to maintain this inequality, the 85 richest try to keep an eye on the others, to make sure that they aren’t up to no good. And this is exactly what companies like Facebook and Google are doing.

Balkan says rather than viewing these services as clouds to store and access data, we should see them more as farms. As ‘users’, we are the ones that are being farmed and sold as products. These companies know everything about us, and – apart from our physical body – they sell all our thoughts, knowledge and desires. The institutions that should regulate these companies are actually supporting them. This multi-stakeholderism is a very serious problem, Balkan explains. Public-private partnerships often allow for institutional corruption, which is now even being codified in our laws. A good example is TTIP where corporations get veto rights over democratic decision making.

Balkan claims that this is a warfare on the public sphere, the commons, human rights, individual freedom and democracy. The only solution is to have stronger democracy and to remove corporate finance from institutional decision-making. Iceland is an interesting example where the pirate party has now become the largest political party in the country.

Although technology can help to enforce stronger democracy, Balkan says that we need to change our understanding of our relationship to technology. Normally we treat technology as a ‘butler’ that responds to our requests. However, when we see technology as a real extension of ourselves and our minds, surveillance automatically becomes a much greater intrusion. Balkan argues that we must extend our personal rights to the technologies that extend us. As individuals, we must have ownership and control over our digital selves, which would be more obvious when we understand our data as part of our (extended) self.

Design has a major role to play in this. Balkan explains that the design of Silicon Valley is aimed at empowering you in the here and now. For example when you navigate with Google Maps. But the cost of this empowerment is ubiquitous surveillance and addiction through manipulation: this is design without ethics. There are alternatives with Open Source designed platforms. But here the cost is very often the convenience and immediate experience. Balkan proposes a new ethical approach to design that both empowers you with a convenient, delightful experience and that protects your data at the same time.

Balkan concludes that there has always been a mismatch between the architecture and philosophy of the web, since the architecture allowed for monopolies (like Facebook) to grow. However, designers do have the opportunity to change this and strive for an egalitarian decentralized typology of (independent) technology.

Next year, Balkan and his team will launch Heartbeat, a social peer to peer platform without spyware. You can read his Indie Manifesto at ind.ie/manifesto.

Kicking the habit

Tijmen Schep reports on the sermon delivered by philosopher and self-styled Facebook rehab guru Hans Schnitzler.

“What? You don’t know who Sanne Wallis de Vries is? She was on TV!”

An evening like the Facebook Farewell Party makes you respect the

significant gap that exists between what geeks understand and what their

moms understand.

Take for instance the sermon by Hans Schnitzler (and sermon is the right expression here). Embellished with philosophical soundbites he passionately and at times rather foul-mouthedly voiced a view on Facebook that most nerds and geeks have probably heard before: we are digitally abused on the internet by big companies, like cows in a dark server farm, milked for our data. However we gladly succumb to this abuse, Hans claimed, as we’ve become Facebook junkies, hard-wired to enjoy the hits provided by the feed of social updates. We’re junkies with a double life too, as we assume the role of dealer, too, when we post our own updates. The whole system creates a growing “attention-economy” in which Facebook users are subtly pressured to present their lives as attractively as possible.

The new social network Minds.com shows us that this economic model

isn’t too far fetched, as it seems to have taken this very idea as its business model. On Minds, every time you read other people’s messages you earn “credits”, a type of virtual money. You can spend this currency in order to push your own messages to the largest possible audience.

When we look at social networks through the economic lens of Marxism we

are presented with a picture of a sophisticated system that has cleverly

commodified human interaction and appeals to our basest desires. This is less innocent than we may think, Hans Schnitzler warns, because “as a slave of our desires, we lose some of our basic human dignity”.

So what are we to do?

A logical step seems to be: quit Facebook. But a hand-count in the Main

Hall revealed what anyone could have guessed: almost no-one

wants to say goodbye to Facebook. For many of us Facebook has become as

inescapable as our mobile phone. It is used to connect us to our friends, find

jobs, hear about social events and so forth. Facebook doesn’t just

appeal to our basic instincts; it also provides a very useful service.

When it comes to either staying on or quitting Facebook we all weigh the pros and cons. And for most people the pros outweigh the cons. But this does not need to be this way. Two things may change this. For one thing, people may become more wary of privacy issues than they currently are… However, engaging people with privacy matters is a difficult as most people think “they have nothing to hide”.

The second option is to build new social networks that are less detrimental to our privacy, so that people will have an alternative to move to when they decide to leave Facebook. All sorts of well-meaning nerds are trying hard to build those alternatives. But unfortunately they are often not reliable (Ello) nor user friendly (Diaspora) enough to entice people to leave Facebook.

The latter is a recurring phenomenon. It sometimes feels like a law of

physics: the more ethical the software, the less user friendly it becomes. This was the primary complaint of speaker Aral Balkan. According to him nerds often think that their tools

will automatically be adapted and used by the non-nerds. This “trickle-down technology” model, Balkan suggested, is not working. We have to make this software sexy and fun, Balkan asserts.

The Facebook Farewell Party is part of a wider push to create audience-friendly campaigns and communications. All attendees were appointed as “soldiers in the Facebook Liberation Army” by Waag Society’s commander-in-chief Marleen Stikker. If they all cultivate General Hans Schnitzler’s zeal, the balance could still tip against Facebook’s current social media hegemony.

Finally: Are you ready to say farewell to Facebook?

Christine van Spankeren reports with a summary of Marleen Stikker’s speech, and her experience of the workshops on offer.

Over nine million Dutch citizens have an account on Facebook. This number is still rising, but meanwhile more and more people are leaving the social network and looking for an alternative. Leaving the Facebook-community is not that simple says Marleen Stikker, one of the founders of Waag Society, a Dutch platform for art, science and technology.

“Facebook is manipulative, they spy on you and they take over your (virtual) identity. The moment when your own sovereignty is in danger – and you get the feeling that you are not the same person online as you are in real life – you should liberate yourself.”

Stikker often hears the argument that we cannot leave Facebook because we have invested too much in it. All of our friends and business relations are on it: it is a source of information on all the people in your social network. Despite this, she thinks that it is possible to leave Facebook.

Take ownership of your data

You can in fact leave Facbook, you can delete or deactivate your account. You can explore new territories and look for alternatives that provide you with complete ownership of your data. There are alternatives to Facebook like Heartbeat, Minds.com or Diaspora. These options were presented at the Social Square at the Schouwburg.

Hide in the network

A second option is to ‘hide’ in Facebook’s network. This option is for people who would like to stay on Facebook. One of the steps is to defeat the algorithm, which can be accomplished when you use an ‘onion browser’ for example. Furthermore, you can also use encryption tools to hide your messages from Facebook’s algorithms.

Rebel

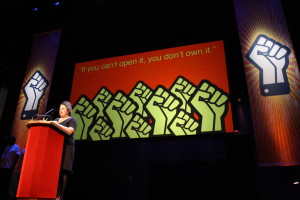

A third option is to rebel. Being present at the Facebook Farewell Party is one way out of many to rebel. When you choose the road to rebellion, you can take action by supporting legal actions or throw a Facebook Farewell Party yourself, for example. Besides that, you can arm yourself with knowledge about coding or hacking. Or help to open up technology, because “if you can’t open it, you don’t own it”.

Stikker compares Facebook with a broiler chicken: in a few years we will be ashamed that we have used it for so long, because every day we learn more about what Facebook is doing with our data.

A network in the Network workshop

If you want to stay on Facebook, but you do not want Facebook to know everything about you — what can you do? This is what the participants of the A Network in a Network workshop were taught during the Facebook Farewell Party.

The workshop was given by three people wearing colorful self-made face masks. There was a long queue of people curious to find out how to become David in this modern fight with Facebook as Goliath. The masked teachers led participants to a room where you could take a picture of yourself. The picture went through a paper chipper and with its shreds you made a face mask. This way you are ‘unrecognizable’ for Mark Zuckerberg.

The main goal of this workshop was to learn how you could build an anonymous network within Facebook. The masks were a part of the workshop to let people shred their current digital identity and to show them how easy it is to make a new one, which only you and your friends understand. One of the other steps included the downloading of an onion browser, like the Tor browser.

The Key to my Heart

In the salon of the Stadsschouwburg two people dressed as doctors helped you to make your own ‘Key to my heart’: an interactive ritual in which you can obtain a new and verifiable digital identity in the form of a cryptographic key. A cryptographic key is a number generated in such a way that it can uniquely identify a human. Here they used the beating of your own heart. The digital identity could be used to sign and encrypt emails. I think this is really awesome and, of course, I made one myself.

I had to stand in the middle a small space, with four screens surrounding me. Then I held a sensor against my chest, so that the machine could find my heartbeat. As soon as the computer registers the sound of the heartbeat, it created my own unique digital identity. Nobody is getting in my mailbox anymore.