In this article, we try to outline the philosophical and technical background that informs the architecture of our web-based project All Sources Are Broken, an online publishing platform that enables cross-referencing media, as well as an artistic experiment about the archive and the hyperlink obsolescence. We also address the artistic practices that contribute to defining the project as a decelerated post-digital strategy, in order to frame it within the context of what we feel like is today the main urgency in the scope of information systems, media and self-education, and cultural activism.

‘A book read by a thousand different people is a thousand different books.’ – Andrei Tarkovsky

In May 2019, we presented our project ‘ASAB—All Sources Are Broken’ in Arnhem, in the context of the conference Urgent Publishing, organised by the Institute of Network Cultures (INC) and in collaboration with ArtEZ University of the Arts and the Willem De Kooning Academy. The opportunity came then from a call for work to which we responded with a proposal for a workshop: the official conceptual framework of the three-day meeting—New Strategies in Post-Truth Time—was the right opportunity for us at that time to explore the project in a different light. In our application, we decided to propose the formation of a Post-Digital Reading Group, whose aim would be to use our online platform to explore what we call the Online Media Source (OMS), starting from a few fragments of text—we would bring along books as working material—and practising archiving using the Web on that basis. That experience was a particularly positive circumstance for us to try to temporarily localise a networked process that is otherwise distributed on geographically scattered hosts, and to observe it happening in a technologically non-mediated context, sitting physically present side-by-side with the possibility to talk to and listen to each other.

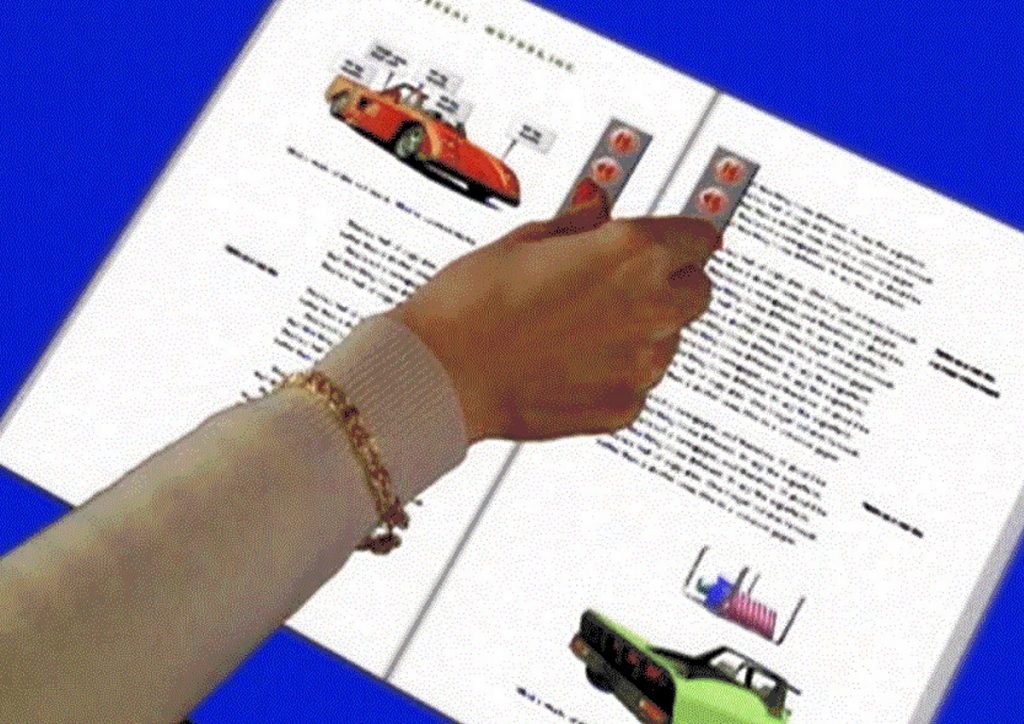

Image of the home page www.allsourcesarebroken.net ©Valentina Besegher

Participants were initially given a rather trivial task to perform via the ASAB user interface, namely a typical content authoring workflow to create records and populate the ASAB database. Along with a set of basic instructions on how to access and use the platform, they were provided with a few selected book snippets and asked to search the Web for any OMS cited or mentioned in the chosen text. An OMS is the minimum unit of the ASAB system, which is constituted by a little fragment of digital information, such as an image, an audio-video file, or a hyperlink publicly available on the internet. The task of ASAB is to retrace the never-ending chain of remediations that starts at some point offline, in the margin notes of a book, all the way ‘up’ to the OMS and ‘down’ again to the books, while rooting this very process in the authors’ words.

Example of a page with drag and drop – www.allsourcesarebroken.net – ©Valentina Besegher

In addition to these re-archiving and re-reading tasks, and to showing our project, we would have liked to open up the discussion about the quality of the correspondence that elapses in-between the spaces of the online media and the text, but for reasons of time, we were not able to reach this moment of analysis and unfold the full potential of the reading group—ideally through a philosophical symposium, or perhaps the more intimate and animated drift of the discussion, during which we imagined having recourse to alcohol and tobacco with the participants. Nevertheless, from a prepared, responsive and highly specialised audience of academics, artists and graphic designers we obtained passionate comments on the UX staged by our online platform, as well as on the proximity of reading and writing, or even updates on the semantic web1 and notes on how far ASAB’s information architecture deviates from that standard.

One of the most valuable results of that experience was certainly the confirmation of the limits of the application, although in the current context, we would prefer to use the term ‘edges’ to refer more precisely to the perimeter within which the project as a whole defines its true potential. We observed how the attempt to play with predefined, well-recognisable models of presentation and content organisation—the platform presents itself as a participative online archive—can easily distract from the original experimental core of the project. And it is precisely in this sense that the edges are not simply perimeter-based limits to define a general scope but become real trigger points of a process that the participants are invited to interact with and respond to.

The web-based project ASAB was born as a cross-disciplinary artistic investigation that draws on multiple areas of interest explored over years of practice carried out independently by Labor Neunzehn in the fields of moving image and sound, and later consolidated in the curatorial activity of our common Berlin experience at Labor Neunzehn. This is a crossroads of professional work and self-taught knowledge, concentrated around the theme of language (understood here more as a recording tool than as expressive or communication ability), ranging from experimental cinema to musical notation, passing through philosophy, media theory, web design and coding. ASAB stages an editorial flow in which the technologies of the book, our brain and the worldwide web are invited (provoked) to interact on multiple levels; a post-digital network whose three main actors are the text (and with it, inevitably, always the author), the reader, and the internet. Somehow, the scene prepared by ASAB alludes to an ontological character of the network—that is to say, the idea that nowadays the categorical essence of the entities is basically established by dynamics of networking. But this is a topic that cannot be explored in the context of the current text and should be addressed separately.

ASAB’s editorial flow fosters the creation of parallel narratives starting from the reading and rereading paths contributed by the users. It starts OFFLINE with the reading of a book, an ancient technology, and continues ONLINE, with the aid of the browser and a few bare editorial steps to reorganise what the citations and endnotes suggest, or intend to suggest. The interaction of these two states in the networking process—apparently simultaneous and yet immeasurable in space and time—gives life to a database of cross-references between texts and non-written sources (at least not in the traditional sense), such as film, sound, image, spoken word. This procedure—which is partly experimental and partly already widely consolidated in the Web 2.0 paradigm2—feeds a dataset, on the one hand, the content of which can potentially be explored and extended without end. On the other hand, it also lays the foundations for a pragmatic investigation into the structural availability of the online resources and the rules that dominate their usage; into the advantages and limits of digital preservation; into the deferral that accumulates in the process of online data migration; and into how the latter acts on the perception of meaning. The cracks, leaks, drifts and open spaces left by these issues are at the core of the ASAB experiment.

Parallel Narratives

Let’s come to the first point. The main effort of an artist’s creative process takes place at the submerged level of the research. It is undeclared work that can last for hours or years, often inaugurating a trail with an unguaranteed destination. The work of art in the age of its infinite digital remediation3 originates from an intermediary relation with fragments, clippings, disconnected resources, fresh and sedimented readings, journeys, traumatic events, memories, visions, and so on. It is a search in the sense of finding and letting oneself be found—namely, an empathic encounter of subjects, which at a given moment of searching find themselves involved in the same event and creating a contact, a new presence.

An example of this ongoing creative exchange between things (to the extent that the seeker and the sought become objects for one another) is the artistic and amateur practices (in the Brakhagian sense of the term4) of found footage and field recording. Here, the original context to which the intentional object belongs (that is to say, how a particular fragment of moving image, a photograph, a sequence of sounds, an objet trouvé happen in space and time) is completely secondary because the action takes place entirely on the level of consciousness, where simultaneous reading and writing processes are in place and both object and subject are somehow reabsorbed in a process that escapes any binary logic. In the emphasis of finding and letting oneself be found, the subject listens to the thing and loses its illusory central status. In order to visualise these relations, let us try to imagine an Observer and an Observed: the point-of-view of the one and the other can define infinite trajectories but will never be able to grasp its own origin, which is a part of the mutual observing event that inhabits the space of the gaze. To this extent, directionality is only a blind spot with no dimension. Who is observing, then?

In the artistic practices mentioned above, the direction does not count that much because what really counts is precisely the opening of the gaze and the temporality that it holds; focusing on the trajectory of the gaze—on the point-of-view of the author and so on—is equivalent to not observing at all. This is like dealing with a multidimensional space with two-dimensional tools, exchanging surfaces for volumes. As opposed to scientific research, where objects need to be abstracted, formalised and replicated in order to be confirmed, there is no expected response to the research activity in the lesson of the objet trouvé. In the end, it is not a question of finding, but rather of tuning into an event.

These very principles and dynamics could be applied, without forcing, to the practice of ‘web searching.’ In the current phase of the ASAB project, we are actively working to build an API (Application Programming Interface) capable of exposing an abstraction of the OMS in an online publishing-oriented data structure. This step, announced a long time ago and prepared since the first development of ASAB, aims to offer online DTP (Desktop Publishing), draft management and client-side PDF printing capabilities. At the moment, our efforts are focussed on the development of a virtual canvas, a decoupled application that allows each user to store and sort their own OMS collections and generate custom, paper-based outputs from them. It was a matter for us, so to speak, to harvest online where possible, what authors sow at the margins of their text—a URL, the title of a film or a painting, the name of a project—while maintaining the reference of these data with their source text. This was done to open up a cross-referenced editorial space whose remediation starts from the offline media and expands beyond it. (That is, instead of getting stuck, in the self-referential circle of the discourse generated on and by social media, which happens online on a daily basis.) We like to think of these PDFs as hybrid outputs generated from the OMS, like amateur appendices to the original text that generate a continuous exegesis and an infinite extension of the citations.

This is a way to rewind the cycle started with the offline text and return back to paper after the passage through the OMS, but also to decelerate the digital by means of reconnecting it to a larger background that contains both books and hypertexts. We wanted to force nonlinear narrative paradigms in web search, and to us, it seemed that the best way to do so was to reduce the distance between the book and the browser, somehow connecting back the technological elements shared by these two objects, such as endnotes and citations (precursors of hyperlinks) in order to let them fall back into a decelerated post-digital context.

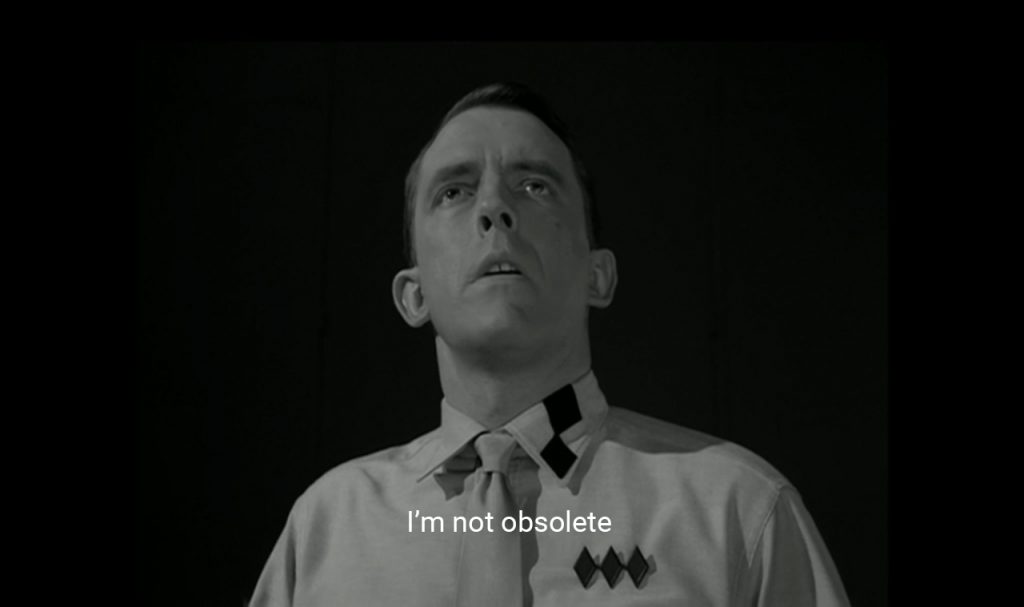

Obsolescence and Acceleration

Before highlighting how ASAB seeks to encourage post-digital deceleration practices, we still need to touch on the second point made in the first part of this contribution, which called to mind the topics of digital obsolescence and offline/online migration. According to Jacques Derrida,5 existence takes place on a deferred basis; it is, therefore, in a state of essential divergence that affects all levels of reality. For Derrida, this ontological dissonance and its resulting flickering would be the constitutive trait of every space of being, the reasons for which ultimately lie in the physical nature of time: that is, everything is always decentralised with respect to itself and, hence, largely unspeakable by language. As media artists, we believe that cyberspace, and the Web in particular, does not escape this logic of delay and decay. Rather, it amplifies it. If the technology of hypertext is not dissimilar to that of the book, then by extension, the Web is equivalent in cyberspace to the library, thus a structured archive for the cataloguing and consultation of written resources that we access through the browser. Books and hypertexts are just some of the cornerstones that govern contemporary individual and collective cognitive activity.

But if as Derrida teaches us the gap between language and mind, and beyond, the mind and the world, is constitutive of existence, we can count on a propagation of the ontological qualities of this gap on a digital level, such as to reposition the space of the difference (the deferral) in cyberspace. By searching the Web for links cited in a book, it is not difficult to come across some discrepancies: not infrequently, hyperlinks are broken, but even when the resource is available, the endless reversibility of the hypertext makes it elusive in its temporal dimension. And it is very difficult to retrace its changes—even if, on the contrary, modifications can be much more persistent than in offline media, as shown by versioning tools, such as Git,6 or large digital archives, such as the Wayback Machine.7 In other cases, hyperlinks can lose reference to any context forever: the domain name changes and one gets redirected to misleading resources.

Now, if we were to see obsolescence as a merely technical topic, it would not be difficult to understand why it is mostly considered a temporary obstacle to a linear ever-improving path—that is to say, a symptom for an outdated status not yet upgraded. Among others, the current research on the Digital Object Identifier (DOI) defines a standard for the persistence of hyperlinks in the digital network system that already offers a concrete way to successfully deal with hyperlinks obsolescence, although this seems for now to be targeted to a precise consumer audience, mainly academics, and often ends up justifying the subsequent implementation of paywalls and closed membership procedures by the Web masters and the administrators of online resources. Similarly, digital preservation processes are mostly oriented towards the creative industries, such as museums, with the disadvantage of leaving out all online resources that do not fall under one of these economic activities.

The financial effort needed to ensure the implementation and maintenance of these online archives and their offline legal entities is such that it inevitably generates a business-oriented production cycle, the achievements of which are not in question here. However, their venture goals (in the end, it will be necessary to justify the costs) open up important questions about the infrastructural context in which the contemporary Web is developed and the space of autonomy, if any, left to billions of Web users involved in the dynamics set in motion by these investments. Again, we don’t want to get into a discussion of issues that would go far beyond the limited purpose of this article, which is to outline our urgency for an online art practice of rearchiving and publishing. However, and this is the point we are most concerned about, today’s technological research on the subject shows very little interest in approaches that see obsolescence as a resource, ending up restricting spaces for autonomy. There is no real possibility for the user/citizen to choose whether to upgrade or to remain outdated, as it is forcibly subjected to a modality of updating that overwrites and replaces the old instead of preserving it.

Beyond what the future of the internet will actually be (if future can still be considered as a subject from the perspective of a post-historical perception constantly undergoing acceleration), it seems to us that the current race to release the next online service largely embodies, possibly at an even more pervasive level, what Paul Virilio described in terms of a claustrophobic saturation of the world.8 And this logic of speed becomes even more pervasive and terrifying when accompanied by the idea that digital networks occupy a sort of immaterial and ahistorical level—opinion that seems to be mainly shared uncritically by the most part of users-citizens. On the contrary, digital media and online technologies prove to be a very much concrete and effective intervention space, which is potentially capable of driving not only the productive but also the information, art, and education life cycles of big cities, which are in turn refactored according to the model of the Digital Factory.

Media obsolescence, the digital decay of online resources, the irremediable inconsistency of the global archive, its deferrals and its own temporality—all this can be thus transformed into opportunities for existential decentralisation, deceleration, inclusion and experimentation, precisely because these disruptions are taking place online with greater force and are capable of bringing out the edges, to rethink the margins not as cracks to be repaired but as new openings waiting to be expanded, to conceive asynchronicity, redundancy, error. Not as weak points of a centralised technology but for their authentic differential content. Rather than reducing all of this richness and variety to the commercial aspect alone, reporting it as a technical debt to be recovered, media obsolescence should be recognised for its content as the bearer of that difference, of that time, and of that history, which the ideology of acceleration does not admit and does not tolerate, and is thus valued as a legitimate source of truth.

Icons of the website / save link + broken link – © Valentina Besegher

The specious flattening imposed by the ideology of acceleration is easily perceptible in everyone’s daily experience on the Web by paying attention to the widening of the scope of application in UX design over the last five to ten years. The gradual and increasingly widespread use of start-up design patterns that are congenitally instrumental to a corporate logic—like, among others, the implementation of CI/CD pipelines,9 the reframing of traditional development life-cycles within agile containers, Guerrilla Research strategies—has emerged over the last few decades as a standard source for usability and consumption. And that has essentially shaped the majority of the online products and services developed at every scale, with a considerable impact on the citizen-user-consumer state of mind. If we wanted to compare the Information Architecture (IA) in which hypertext operates today with urban planning, the recent development of the Web would lead back more to the experience of the shopping centre, rather than to that of the city. Just as in a shopping mall, IA can work to create paths and barriers to guide the user’s choice at the expense of strategies that support discovery and sharing activities, and force a space entirely oriented towards consumption.

The incredible speed with which mobile device softwares such as car sharing, voice AI assistants, socialising, food and goods delivery, and healthcare applications keep spreading in large metropolitan areas—encouraged by the presence of cultural and linguistic barriers, a wider dislocation of services, and an ever-changing, wide base of new consumers—has helped to install an ‘app-like’ digital mind-set in the user-citizen, whose acceptance is as widespread as it is unconscious.10 And this is not to mention that the migration from offline to online does not take place in a unidirectional way, but is active out of natural sympathy between the structure of our mind and that of the digital networks: a cycle that is self-feeding and retroactively re-enters the individual experience, acting on the contents, the social coordinates and priorities of the subject, and operating in a significant way on the emotional universe, on the perception of the body, on the relationship with power, life and death, which continue to manifest themselves within our individual and collective experience and shape us as humans.

Video still of the ASAB lecture performance – ©Valentina Besegher

By fostering decelerated web-search practices—should we call them obsolete?—as well as pointing out web browsing in itself as an art practice, our online platform tries to encourage a post-digital approach to the archive that takes into account failure and deferral as a constitutive multifaceted trait of digital networking technologies. We believe that the latest development of the online networking infrastructure towards a centralised, service-oriented11 hub has added new layers of complexity to the language transforming our perception of meaning and the ability to read and contextualise the sources. When it comes to the digital, words such as speed, present, communication, reversibility, and synchronicity should be considered ambivalently for their dual effect (online/offline) on our relationship with time.

Personally, we experience the present modality of interacting online as predominantly ruled by a widespread economy of speed that is then sublimated and reabsorbed in our bodies. This urgency for velocity and immediacy is and wants to be predominant precisely because it is fuelled by a dream of progressivism and an unlimited growth of desire. ASAB’s art practice instead uses the browser as an online catalogue for reconnecting the cycle of remediations that propagates from offline texts into online media. And it generates concrete physical outputs (appendices) from the chain of deferrals that accumulate in the space of this very migration of language and meaning, in order to support asynchronicity and address disruption as a unique opportunity for experimentation and observation.

© Valentina Besegher

Labor Neunzehn is an artist duo composed of Valentina Besegher (1976, Milan), an avant-garde filmmaker, live video performer and visual artist, and Alessandro Massobrio (1974, Turin), a composer, musician and sound artist. Their research addresses a cross-disciplinary discourse on time-based art, involving expanded cinema, modern music, publishing and critical reflection on new media art, with a specific focus on the migration of these languages between the online and offline domains. The duo operates in the namesake project space in Berlin, which acts as a research and curatorial platform for the production of exhibitions, performances and workshops, and is committed to the presentation of collaborative outcomes and hybrid formats.

References

Bibliography

Brakhage, Stan, ‘In Defense of Amateur.’ Filmmakers Newsletter 4 (1971): 9-10.

Derrida, Jacques, Of Grammatology. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998. Virilio, Paul, The Administration of Fear. Los Angeles: Semiotext.