In the game of online visibility; cuddly animals, selfies, houseplants, bro-culture, health mantras, and Fiji water bottles are now strangely powerful tools. It is no coincidence that these images and sub-cultures are also commonly utilized in the rapidly growing category called ‘post-internet art’. There is a definite link between the kinds of images and meme strategies used in many post-internet practices, and the swift proliferation of post-internet art into the gallery and collecting scene. Whitechapel curator and artist James Bridle stated:

Enlarge

Bridle's quote about the gallery being part of the internet, and not the other way around, indicates a crucial step towards recognizing the web 2.0 infrastructure that has now become a vital part of the art world. However, despite the many exhibitions focussing on post-internet practices and their interrogation of technology and internet spaces, very little inquiry has been done on the effects of the architecture of communications technology on representation and networks in art – how it is taken advantage of, and what biases are enforced towards visibility and content. For example, the Whitechapel’s recent major retrospective Electronic Superhighway tries to bring an art historical backing to an often only contemporary investigation of electronic and digital art. Though the historical research certainly aids in canonizing a medium which has for a long time been the unwanted child of the art world, the construction of web 2.0 and the mentalities it engenders remain an elephant in the gallery. As a result large questions such as the relation between Katja Novitskova’s cutesy mammal cut-outs and the rapid rise in post-internet art exhibitions are not put to the fore. One may also think of the curious parallel between the Canadian cellular company Telus’ marketing strategy of featuring baby animals in all of its ads, and Novitskova’s own usage of a similar aesthetic.

Enlarge

Instead, the focus remains on an art practice based investigation in areas such as Instagram culture, and does not turn the lens around to look at how these same technologies are creating hierarchies in art representation, and how many artists and institutions are beginning to adapt strategies based on this new hybrid online/offline space. The name ‘Electronic Superhighway’, although apt for the exhibition’s historical lens, still carries with it the air of internet cowboy, barrier-less freedom – a rhetoric engrained from its early tech formations in hippy-liberal Silicon Valley. With the amount of press on big data and surveillance, it should be clear that this illusion is not accurate. From the undersea networks that structure and carry the internet, to web 2.0’s digital architectures of linking, there are many echelons and restrictions within the freedoms and conveniences afforded by our ‘friendly’ every day devices. As art institutions, art practices, and collecting begin to rely upon and integrate communications technology into their methodologies, important questions as to how this infrastructure impacts success, and power are crucial. In examining how artists involved in the beginnings of ‘post-internet’ art formed their own network of circulation, it is evident that not only is web 2.0 not a solution to opening up representation or creating a more horizontal playing field, its current network structure and the strategies used by certain artists are in fact reproducing existing hierarchies which risk further implementing capital interests into what kinds of art receive recognition.

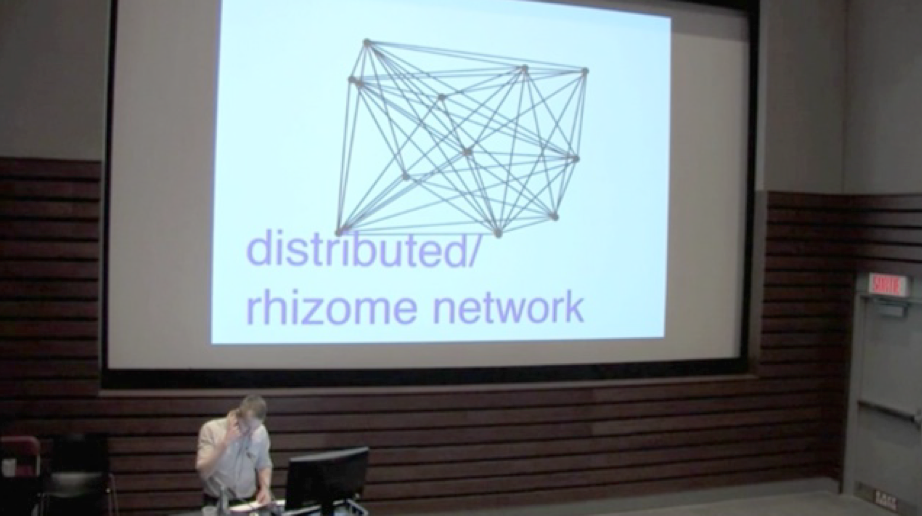

Network Formalism

Enlarge

In 2011, during a lecture at Concordia University, Montreal, Canada, titled ‘FREE ART’, artist Brad Troemel proclaimed:

Art’s role in society has undergone many drastic changes. It is due for another right now. This is a new gospel, intended for a generation of artists tragically forced to collect cynicism as their only reliable conviction. To them the art world is not only hopelessly outdated, but exploitative as well, like an abusive grandpa working in the distance. This speech endorses new ways for art to exist in the twenty-first century, by using the technology we already have, as a means to efficiently distribute art freely among viewers. You haven’t read about it in books, and you haven’t been taught it in school. I’d like to spend the next 20 minutes, outlining how to change everything about art completely.

Taking a guru-like tone, Troemel’s words give the illusion of providing a tactical strategy to the younger generations of artists in the audience, aimed at a shift in the production and circulation of art towards a less hierarchically organized and exclusionary formation. Using an analysis of the infrastructure of the internet as a decentralized network, Troemel proposes a way to use communications technology to break institutional and market barriers for artists, presenting this vision as a radical and utopian plan, one that would ultimately create sustainability in an otherwise precarious industry. However, from the perspective of 2016, where Brad Troemel enjoys considerable success in New York, his plan should be examined in terms of its own reproduction of the hegemony it originally appeared to be in opposition of.Troemel is a potent example as he has been a prolific writer on his own practice and discourse, not because he is the sole artist doing so. Rather, he reveals how artistic practices are not only effected by online architectures and social media pressures – such as the ‘share or die’ feeling of internet attention/trending economies – but are now actively incorporating and manipulating these same pressures to their benefit. It is no coincidence that many digital and post-internet artists are in their twenties and represent a fairly young portion of artists circulating in galleries. Often labeled under the dubious term ‘Digital Natives’, many of these artists grew up surrounded by communications technologies and its mentalities. In a cultural field increasingly ordered by precarity and corporate numbers, many young artists turned to the internet as a medium and platform that was readily available to them. Looking to obtain representation and security above all else, Troemel can be seen as having grown up in this context. Troemel’s practice is one that critically understands the linking and corporate infrastructure of the internet, and has effectively sought to reproduce it in order to maximize his own gain. The strategy is one I call ‘Network Formalism’. Network Formalism adopts the power formations of communications technology as it currently exists under primarily corporate and marketing interests. These communications infrastructures privilege content on the basis of many of the same traits valued in the elite circle of art – such as mobility, flexibility, connectivity, novelty and trendiness. As such, it should not be surprising that post-internet art is becoming a key player in the art matrix.

The Adaptable Web 2.0 Subject

Although the socio-technical infrastructure of web 2.0 emphasizes similar qualities as art in terms of what becomes trendy and popular, due to the personalized, fragmented, and real-time nature of the web, characteristics such as mobility, trendiness, and transience are emphasized even more due to the infrastructure itself, which must filter massive amounts of content and information every second. As these networks operate on an increasingly personalized level with many people maintaining relationships, work, hobbies and education through their devices, social media allow for the further integration of capitalization into everyday processes. This engenders the same cravings for representation, speed and visibility that social media platforms’ corporate numbers game is attuned to, integrating these qualities as a normal standard of living. Under this anxiety and intense fusion with their networked devices, people might experience feelings such as a vacation not being real unless it is publicized in the form of ‘vacation porn’ photos on Instagram, and even more, not unless those catchy frames receive many likes and comments of approval. The personalized integration of both the mentalities and the technology helps to condition a prosumer or ‘do it yourself’ (DIY) mentality, which theorist Lane Reylea has characterized as a pivotal aspect of networked creative economies. For those looking to thrive in web 2.0, they too must adapt to be self-sufficient, connected, and flexible, building up their profile and network.

The adaptable, self-produced subject is also indicative of the continuation of the entrepreneurial and managerial attitude that Eve Chiapello and Luc Boltanski theorize as the networked, flexible model prominently used in capitalist formations since the 1990s. Describing the break from the very strictly classified and contained organizational model, Chiapello and Boltanski note that this rift also indicates a shift in the metrics of legitimization. Rather than having legitimacy be determined on an exclusively hierarchical level within an institution, legitimacy and importance become more about the extent to which a managerial subject is able to move, make connections, and adapt:

The manager is network man. His principal quality is his mobility, his ability to move around without letting himself be impeded by boundaries, whether geographical or derived from professional or cultural affiliations, by hierarchical distances, by differences of status, role, origin, group, and to establish personal contact with other actors, who are often far removed socially or spatially.

Circulation, mobility, social connectivity, and flexibility all become the main tenets of legitimacy in the framework developed by Chiapello and Boltanski. Network Formalism is an adaptation of this managerial subject, which upholds these main characteristics as that which determines success. Though this model is not exclusive to virtual spaces, the personalized and decentralized nature of communications technology functions as a facilitator for this managerial model and the networked subject, allowing for easier access, mobility, and increased connections. The swelling amount of individual promoters, prosumers, and DIY initiatives suggests the subsumption of these attitudes into everyday life facilitated by technology.More questions need to be put forward as to what kinds of new pressures and subjects are formed when these networks become even more engrained in artistic practices. For many artists using the web, their ability to take on this kind of entrepreneurial mode defines their success. In listening to the full video of Troemel’s presentation, it is clear that he adopts an entrepreneurial DIY attitude, evident even in the quote. This adaptation allows him to purposefully re-create the corporate network with the aim of producing the optimal conditions for circulation, and by extension his own visibility and representation as an artist. The proliferation of these kinds of strategies has important consequences not only for artistic subjects, but also for what content is represented in museums, and what is left out of the loop.

The Art of Flex

In 2009, Brad Troemel and curator Lauren Christiansen moved their artistic project called ‘The Jogging’ onto the aggregate image blog Tumblr. It initially began as a project which combined disparate images from around the internet with Photoshop and then posted these new compilations on the Tumblr blog, accompanied with labels that loosely mimic the format of gallery artwork labels and extensive tags. Troemel and Christiansen were not the only contributors to the blog. It also hosted contributions from a close group of artists working in a similar vein of art and distribution including Artie Vierkant, Andrew Norman Wilson, Haley Mellin, Jesse Stocklow, Spencer Longo, and Rachel Milton. Although it functioned as a platform for posting all of these artists, it operated more as an umbrella corporation, keeping a fairly strict adherence to its format and aesthetics. As the site increased in exposure, it began to open up its format to allow outside members to submit possible postings for the blog.

Both Troemel’s writing on this project as well as its form and organization demonstrate a critical knowledge of the corporate and hierarchical interests that structure the interfaces and social networks it relies upon. It is important to emphasize that this is a pro-active move that purposefully harnesses the infrastructure of the internet, rather than being a helpless condition of the internet itself. This strategic Network Formalism is evident in the way the project is managed and organized, as well as its aesthetic content. As the project is a self-produced, self-organized initiative, it is congruent with the DIY and prosumer-laden culture of web 2.0. Troemel’s text ‘Productive Systems’ outlines the required characteristics upheld by Troemel for successful ‘internet-organized’ artist projects. In this text, Troemel identifies three key characteristics for success: ‘the aesthetics of interfacial architecture’, ‘the quality of relational value among participants’, and ‘the commonality of visual content produced’. In all three areas an adoption of the managerial subject described by Chiapello and Boltanski and an astute awareness of the corporate biases and hierarchies of the internet are evident.

As the initial quality used to outline his strategy, ‘the aesthetics of interfacial architecture’ stipulates that in order to be successful, one must understand the ‘aesthetics’ or design of the web infrastructure that one is utilizing, and then adapt to this architecture. Troemel states quite clearly that this strategy contains no desire to change or interfere with the interface it adopts. Quoting Langdon Winner, he writes: ‘the adoption of a given technical system actually requires the creation and maintenance of a particular set of social conditions as the environment of that system’. Already a formalism in the sense that it is trying to re-create the exact conditions and structure of an interface, the tactic here is one of complete mimicry and integration into the corporate infrastructure. In the case of ‘The Jogging’, this means adapting to the restrictions of Tumblr as an image-aggregating social network, which focusses primarily on links, liking, and sharing as a means for representation and circulation.

By extension, linking and circulation become the primary forms for legitimacy and visibility that Troemel pushes forward, as opposed to content. This value formula in terms of representation, builds on what media theorist Richard Rogers has called the new ‘power laws’ of the internet, which function primarily off of linking and liking structures. The more traffic that can be generated through a node or through a particular post, the more it strengthens that point as a node within the network. If one can get nodes significantly higher up on the link hierarchy to connect back to them or like them, then the boost in visibility is likely to be even better. Specifically for Tumblr, the more traffic a post generates, the more likely it will figure on the aggregated image feed of other Tumblr users, and therefore the more it stands to be re-blogged and circulated onto other feeds. Consequently, this criterion prescribes a ranking of artistic practices based primarily on the extent to which they can gain circulation and representation.

Interaction and Connectivity as Ultimate Value

The second quality Troemel identifies is ‘the quality of relational value among participants’, which focuses on re-creating the social conditions required to maximize weak-link connections. The network structure set up by the linking and liking power laws of web 2.0 positions nodes and individuals as always in relation to another point, platform, or data set. Pairing this with theory, Troemel uses Nicolas Bourriaud’s theory of ‘Relational Aesthetics’ to describe the best social environment for corporate interfaces. Relational Aesthetics establishes the interaction and connectivity of a given set of actors as the ultimate value, placing it over the initial object or content which aided in bringing these actors together. Within the context of networked economies and the managerial subject, relational aesthetics is in fact the status quo due to its focus on creating connections and links, as well as its openness and increased flexibility to fit within a context. By following the logic of ‘relational aesthetics’, Troemel thus has adopted a format which fits perfectly with the linking structure of the web and the managerial model. Drawing from Boltanski and Chiapello, Reylea describes this transient, weak-link, ‘connectionist’ determinacy as especially optimal for circulation and mobility:

[O]ne way in which networks profit from the heightened mobility is by favoring casual,weak ties over tight, long-term commitments, so as to increase the prospects of fortuitous,happenstance encounters that lead outward from one communication nexus of group, enabling communication to expand by incorporating new connections while maintaining old ones as latent and re-activatable. Such conditions shed loyalties and identifications and become instead more mobile promiscuous operators who mesh seamlessly with the system’s mobile promiscuous operations.

The current technical and algorithmic infrastructure of most social media platforms, including Tumblr, is based off of weak linking structures, thereby embodying the ‘mobile promiscuous’ systemic character described in the above quote.

The Making of a Decentralized and Real-Time Brand

Troemel’s use of ‘relational aesthetics’ under these conditions positions him as the optimal ‘promiscuous’ operator for these interfaces. ‘The Jogging’ reflects this as an organization, as it expands its overall nodal power through allowing multiple contributors to move in and out of the platform, maximizing its overall weak-link capacity by incorporating several people’s networks into one project as opposed to simply relying upon a single person’s connections. The project’s contributors would create other sites and projects, but each would link back to one another, creating a continuous chain of connections and references. The project’s initial strategy of not including any authorial signatures on ‘The Jogging’ is an extension of its permeability and mobility, allowing the work to better move through different contexts, links, and networks because it does not get weighted down by explicit ownership or description. Adding to this, all posts on ‘The Jogging’ utilize extensive tagging and linking in order to heighten the post’s reach and circulation.

Extending this concept of the relational, the final criterion for ‘Productive Systems’, ‘the commonality of visual content produced’, is the extent to which an internet art practice can utilize the decentralized structure and real-time nature of the web to its advantage while still maintaining a consistent format or brand within its chosen platform as set up by both the interface and its administrators. For ‘The Jogging’, this required setting up a managerial format that enabled contributions from around the world, but that required that all content submitted be consistent with the blog’s overall format and in dialogue with the previous posts. These restrictions allowed for ‘The Jogging’ to build its reach of linking and liking through the subsumption of another contributor’s network while keeping its brand and identity as an overarching node in the web. ‘The Jogging’ quickly fit into the logic of Tumblr, building a consistent identity, and a responsive community and participants, tapping into a valuable visibility mechanism. Elspeth Reeve’s article ‘The Secret Lives of Tumblr Teens’ reveals just how lucrative successful young Tumblrs can be (and the not so hidden corporate barriers of Tumblr); one especially potent example in Reeve’s text being the now defunct Tumblr star ‘Pizza’ whose adoption of the Pizza persona and brand made her an online celebrity almost overnight.

Already the strategy of adapting to the interface architecture has a distinct effect on the artistic subject. These three criteria turn the artist into a highly-tuned administrator who diligently monitors others while also understanding that they, the artists, in turn are being observed. This is consistent with Niklas Luhmann’s conception of the ‘second-order observer’ in risk societies. Second-order observers exist in a hermetic realm of self-observation, stemming from a high degree of cognition that they are being regarded. This produces subjects who must react and plan their own actions based on observations of the environment and their resultant hyper-awareness of themselves, thus further integrating the focus of weak-links and adaptability into the formation of everyday actions. In essence, the overtly relational and social manner in which ‘The Jogging’ operates willingly enforces the fragmented position of the flexible managerial subject, whose value is rated on weak links, loose connections, and their overall relationship to economic and reputational capital.

The pressure of how artistic projects are legitimated by using all aspects of social life as instruments to push forward their link value on the internet is thus integrated further. The constant consciousness of both internal and external observation is an extension of the relationist aspect outlined in Troemel’s criteria for successful online platforms but also underlines the unstable reliance on audience acceptance and numbers for survival in these network formalist strategies. The artists functions similarly to the corporate social media ‘filter bubble’ for whichever social media platform they operate on, creating and structuring content to keep all viewers intrigued and sharing their feed, thereby maintaining their prominence. Similarly, they accelerate the rate of production willingly, understanding that the more content they push online, the more chance they have of being seen. Consequently, this also increases the intensity with which contingency, flexibility, and shallow connectivity are enforced upon the participants.

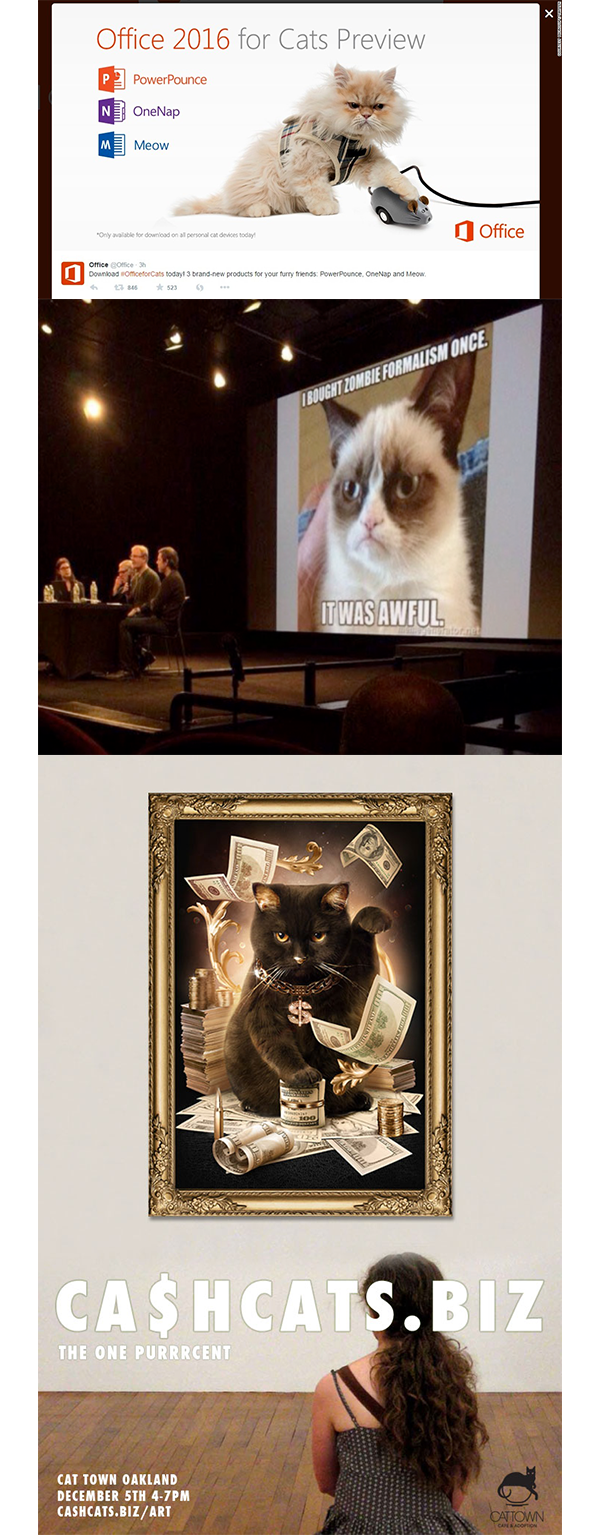

Aesthetics of the Post-Internet: Zombies and Cats

Enlarge

Taking on this relationist strategy, the creation of platform type projects like ‘The Jogging’ and DIS Magazine, has become a key strategy in upping nodal power, and enforcing the post-internet network through amassing weak-links. The fairly lose and open ended character of the post-internet movement, has helped these multi-participant/project creations, enabling a wide range of practices to be collected under one whole. For example, although DIS Magazine is its own artistic collective, it frequently publishes and hosts work from other post-internet artists, allowing more networks to be collected and fostered under its heading. The high exposure DIS has received as a fairly young initiative – including the title of 2016 Curators of the Berlin Biennial – speaks in part to their networked-managerial capacity on the internet. Post-internet has established a very strategic niche, and critics such as Brian Droitcour have aptly described it as a movement and aesthetic that is as ‘thin as it is opaque’, with its most common description being ‘I know it when I see it’.The umbrella platforms created by post-internet artists gain from this open-endedness, utilizing it to further extend their visibility. Parasitically morphing from one form to the next, always using each moment as a bridge to the next link, post-internet art moves through galleries, documentation, text, social media, and websites, activating its carefully crafted nexus of weak-connections.

Enlarge

This intent focus on circulation and visibility in turn effects the kinds of content and aesthetic images which are produced. The aesthetics are both a by-product of Network Formalism and facilitator for the circulation and mobility of the image through different geo-locals and networks, fluctuating between offline and online manifestations. In order to promote the kind of reach and circulation necessary to achieve higher prominence in web and gallery representation, images produced as part of these practices are often highly superficial, glossy, and seeped in indifference. Brian Droitcour has aptly described the effect of these practices when encountered in a gallery format, stating: 'Post-Internet art object looks good in a browser just as laundry detergent looks good in a commercial. Detergent isn’t stunning at a laundromat, and neither does Post-Internet art shine in a gallery.’ He further added that upon visiting Rachel de Joode’s exhibition he felt like ‘an intruder’ who was in the way of the flattened work’s preening for the lens of a camera – a reference to the frequent use of high-gloss, evenly-lit documentation of post-internet gallery exhibitions as a further site for circulation online.

Carefully crafted documentation becomes another point for representation and circulation, as it then morphs into another opportunity for reference and linking for the practice online. Easily digestible, minimal, optimized for screen viewing, and full of one-liners, the aesthetics of these kinds of practices has been coined ‘Zombie Formalism’ by Walter Robinson, due to the almost brainless and reductionist quality of the work and its resemblance to modernist aesthetics. The Zombie aesthetic is an extension of Network Formalism, helping to bridge its reach into online and offline spaces. Often described as ‘liquid’, these aesthetics easily adapt to gallery spaces, text, online formats, documentation, and object forms, fluidly giving momentum to a work or artist, and therefore boosting the overall network exposure and capital. It is this kind of mobile and prolific practice that makes curator James Bridle’s acknowledgement of the gallery as being part of the internet not only valid, but a crucial understanding of this evolving matrix. Zombie Formalism is not exclusive to offline or online worlds, but parasitically uses any opportunity as a further avenue for circulation.

Images from top to bottom: Microsoft Office 2015 April Fools advertising prank, 2nd Image from the School of Visual Arts, NY panel ‘Zombie Formalism, and Other Recent Speculations in Abstraction’. 3rd Image taken from the website ‘Ca$hCats.biz’

Although Zombie Formalism is a fairly accurate description of this kind of work’s aesthetics, cat memes are a more apt model to describe how this aesthetic functions as an extension of Network Formalism, and why it is able to circulate easily. Cats are fluffy, cute, neutral, widely appreciated across a range of ages and demographics, and often share a general disdain and indifference for their caretakers. They are also one of the most widely shared and popular topics on the web because of these qualities. For people who have owned cats, there is also a sense of community, of being part of the ‘inside joke’ of whatever action the cat in the cat meme is portraying. For instance, if the meme is of a cat running into a wall, they are fondly reminded of the time their cat mistakenly ran into an object. The extent to which people will pause to look at cats on the web is underscored by the fact that cat images have been used as activist tools to spread messages and prevent sites from being shut down. If cats could collect money off of their links and likes, then many of them would be internet billionaires.

These qualities of cats make them extremely conducive to networked economies. Due to their neutrality and their popularity, they stand less of a chance of being filtered out by algorithms on most commercial social media platforms, which are in place to keep users happy by supplying them with content that aligns with their preferences and beliefs. This means that cats stand a greater chance of being circulated and of being seen just by virtue of being palatable across a wide range of people and geographic locales. Cats are also able to circulate through different language barriers, aiding their mobility. Similarly, their high popularity means they will receive a lot of clicks, links and shares, further propelling their reach and hierarchy in web topology. Within the over-stimulated atmosphere of the internet, cat memes are quickly and easily readable, which in turn increases the possibility that they will be shared simply by virtue of not taking a lot of time or attention to enjoy. In this sense, the indifference or uncaring that Droitcour felt in regards to Rachel de Joode’s work, is perpetuated by zombie formalist artworks, as the content which is most easily circulated is not heavily aligned to beliefs or ideals, nor does it take time to consume.

Inside Jokes and Privilege

The aesthetic content produced by post-internet artists functions along similar lines, using meme-like qualities to circulate through artistic and non-artistic networks. However, unlike cat memes, they have a higher incidence of inside-joke and internal post-internet community references, and often appeal to the weird, offensive, meme culture of the internet that rears its head on forums like 4chan and reddit. As Andrew Durbin has said about ‘The Jogging’,

It’s never a joke anymore than it’s not not a joke; sub-ironic in its dreamy, endless scroll of user-submitted images, it’s a post-joke. It’s actually very “bro”, a category that is not only purveyor of the joke or prank but its victim too: fail videos, the flat affect of homoerotic (but often homophobic) fraternity, of the pluralized “experience of maleness” and its constituency (brands: Five Hour Energy, Xbox, Powerade; hyper-gendered bodies: male, female; athletics, the gym). The Jogging bros things, communalizes them by imbuing diverse objects – iPhones, a tennis ball, a soda can, a watermelon – with fraternité, establishing an excited sense of things as being related in mysterious ways, like university freshmen who discover a common, if abstract, bond with other ‘brothers’ in a frat house or sports team.

The inside-joke quality of the work enforces its network strength, as the internal self-references allow for a continual re-establishment and activation of the extensive collection of weak nodes. It also serves the necessity of distinguishing itself as artistic content to those in the know. However, because representation and mobility are still the key goals, the references tend to still be obliquely hidden enough to not shut down sharing and liking from non-art viewers.

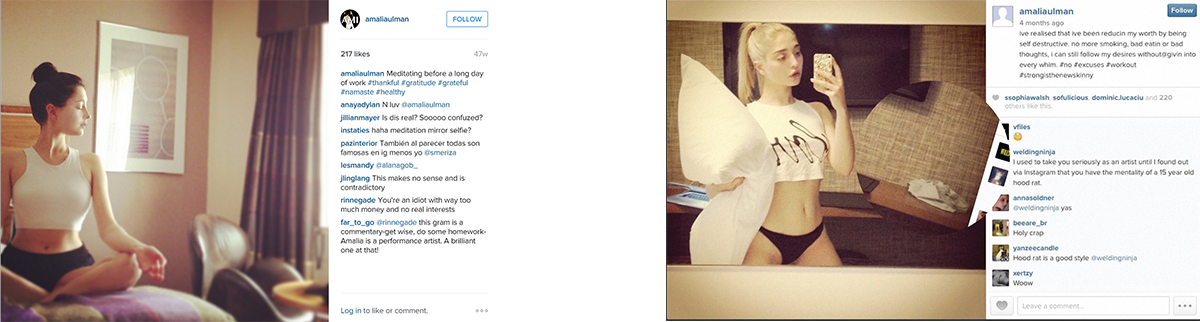

Enlarge

For many encountering the Instagram of artist Amalia Ulman, they will have done so because Ulman has successfully recreated the gendered experience of a female Instagram account – playing to the tropes that attract links and liking through hate, voyeurism, infatuation, and celebrity. She has stated publicly that she played to the trending topics and mentalities on Instagram, claiming ‘it is easy to increase the likes by using shortcuts to popularity, like following the trending topics. If you are using the Photoshopped image of a woman and a bunch of popular hashtags, the likes are going to go up.’ Elsewhere in this same interview, Ulman discusses the various kinds of personas she plays that are popular on Instagram, as well as her relationship to other art practitioners. This fluid integration has garnered her over 90,000 followers, many of whom have no connection to the art world, and often do not know that Ulman’s Instagram is an art project. The mass of followers plays well to the architecture of the web, and establishes her as a fairly visible node in the linking power laws of the web. Her identification of the project as an art piece is what differentiates it from other Instagrams, while her high nodal status continues to assure that she has a fairly high representational profile online.

There are many consequences that can result from these kinds of strategies in the long run. Although social media platforms may give the appearance of opening up the playing field, they ultimately still have privileged content and barriers which do not lead to any automatic change in the global hierarchy, especially with strategies like Network Formalism. Content which is non-political will remain the most easily circulated, ultimately not aiding in re-structuring the precarity and inequality. Not only do these strategies re-purpose existing power formations, theyperpetuate and increase the overwhelming presence of market pressures by actively integrating all aspects of everyday life into the calculation of representation and legitimacy in art.

By mimicking and leveraging off of corporate interfaces that are extremely personalized which and prey off of social life, these artists help make these elements a regular factor in how art is marketed and represented. The networks promote an even more accelerated and flexible subjectivity, as they are ill-equipped to promote practices that by virtue of their own specificity, political nature and depth, cannot disperse as easily through networked environments. There are many practices which do not benefit from this kind of framework, and as has often been pointed out, this strategy serves an often already privileged group that does not include discussions of gender, race, or access. When walking through exhibitions like the Whitechapel’s ‘Electronic Superhighway’ there should be questions as to how these works came to be selected, and if it was because of their carefully crafted online presence.

The Responsibility of the Social

It is important to stress that these strategies cannot be deduced to simply a symptom of the dominance of corporate internet infrastructure. It is vital to recognize that this is an aggressive harnessing of these architectures by artists as means of gaining the necessary capital to integrate into galleries and institutions, rather than solely the fault of the technology itself. Michael Sanchez’s widely cited article ‘2011, Art and Transmission’, is one of the key culprits of this mis-identification, as he argues that these networked online artistic practices are the result of being instrumentalized by technology. To quote Sanchez:

But at this point, it has become impossible to ignore that these networks are technical before they are social, and that the life in question is both biological and informatic, as Foucault and others predicted long before Agamben. Instead of institutions producing subjects, we have apparatuses capturing organisms. Both the informational form and the affective content of contemporary art are optimized for an apparatus that is increasingly dominated by feedback between the iPhone interface, the feed, and the aggregator, not the institutional structures of the gallery and museum.

Note that Sanchez diagnoses these art practices, or the art world, as ‘technical before they are social’, and dominated by the data aggregate technology. This analysis causes Sanchez to misconstrue several key points around the sudden rise in visibility of ‘meme’ aesthetics and art practices within the market.

To him, the zombie formalism of the artworks, their meme-like tendencies, and group feedback mechanisms are the result of being instrumentalized by capitalist technologies. He fails to take into account the self-aware role these groups actively play in mimicking corporate network infrastructures, their aggressive social promotion, and their involvement in integrating these kinds of strategies into a specific sector of the art market, which Sanchez over-generalizes as the art world. Sanchez’s mis-identification allows an avoidance of responsibility on the part of art and its current market, by solely placing the blame on the technologies. By bestowing the brunt of criticism on the technology itself, there is no responsibility placed on an art market which champions network strategies due to their ability to move, make connections, and form their own market and cultural capital. Sanchez’s mis-identification is especially dangerous because it does not call for any charge on art for further aligning market and capital success with what becomes legitimized as art. Post-internet artists are quite tantalizing to the market for a number of reasons. Due to their reliance on the inherent infrastructure of the internet, these artists are constantly posting new content and moving from site to site in an effort to remain visible in an attention economy. It consequently enforces the market’s focus on the trendy, the mobile, and the new, and further entwines these as defining characteristics for success.

With market trends constantly in flux, if emerging art is not continuously moving, networking and adapting, then it is disappearing. Through their re-creation of the corporate structure of the internet, these are all characteristics post-internet art has adopted, making post-internet the perfect vehicle for the art market by virtue of their own mobile managerial mode. Most of the artists in these movements being under 30, they have the added appeal of youth, a favorite target of art, media and capital. As Lev Manovich astutely quotes ‘consumer and culture industries have started to systematically turn every subculture (particularly every youth subculture) into products.’

Creativity and Exploration as Gentrified Memes

Enlarge

In light of the extensive use of Richard Florida’s theories of the creative economy to develop policy across the world, it is clear that Chiapello and Boltanski’s pairing of the ideal capitalist with the image of the artist is no longer just a theory, it has definite concrete impacts as it is being implemented as a market and production incentive by policy makers, and by corporations. Florida’s chapter on the ‘Bohemian Factor’ is particularly salient, although the frequent use of the terms ‘creativity’ and ‘cultural soft power’ in relationship to finance and global competitiveness included in policy in places like Singapore, Vancouver or Japan, are even more potent examples. Promoting creativity, flexibility, and individual autonomy is not inherently a bad thing. However, in a competitive global marketplace, the question needs to be put forward whose creativity, whose intellectualism, whose freedom is actually sought out and fought for.

As evinced by the mass gentrification in San Francisco due to the influx of elite tech and commerce organizations flocking to be near Silicon valley – something which is tellingly overlooked in Florida’s use of the city as a case study for creative economy success – it is not creativity and exploration for all. Instead it is only a privileged few who can withstand the pressures of the market, and who likely already possess a wealth of resources. Art, already no stranger to being implicated in gentrification schemes, becomes even more lucrative under the ‘creative economy’ as unique cultural capital, drawing resources and elite employees/employers into cities. Art’s drive for newness, flexibility, internationalism, and the anti-institutional make it an even better vehicle for these pressures.

Network Formalism as outlined in this essay accelerates these processes by validating itself, using the same qualities desired by the market. It also re-enforces these conditions in the artistic subject and content produced. Even though these strategies of Network Formalism are highly social and connected, it is in a manner which is equally competitive and individualistic, aiming to utilize every link, node, and connection as a potential avenue to get ahead. It promotes the goal of carving out a space of representation for oneself and recreates the conditions which only privilege trends, capital, and existing hierarchies, without creating any sustainable long-term plan or collective action. This means that even though participants in these strategies may coalesce as a group, there is still the knowledge that only a select few will stand a chance at profiting, and therefore still encourages individualist mentalities.

Implications and Options

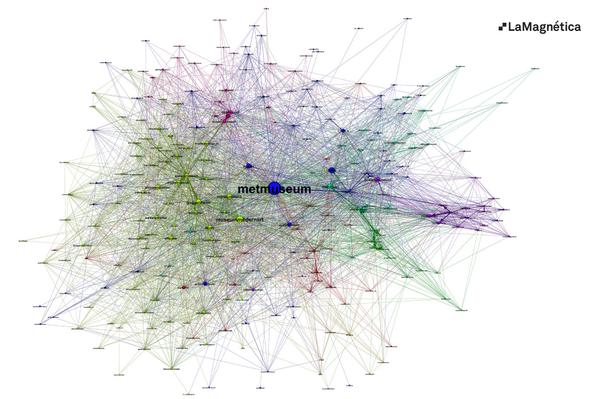

There are further implications to consider when looking towards the future of art institutions and art collecting. What post-internet strategies point to, is the importance of socio-technical networks and infrastructures in society, and how these networks are becoming increasingly more integrated and complex. To quote theorist Suhail Malik, ‘systems, infrastructures and networks are now the leading conditions of complex societies rather than human agents’. In thinking along link hierarchies and representation on the web, there is also the critical consideration of what will happen when large powerful institutions get over their initial baby steps in web 2.0 and truly begin to harness its power through their own network strategies. The online race for visibility amongst the larger museums is just beginning to really develop. In 2014, digital agency La Magnetica announced that the Metropolitan Museum currently commanded the majority of online web traffic ,meaning it had the largest online audience in comparison to other national institutions. It is certain that as these kinds of larger bodies begin to craft their presence online, it will have concrete impacts on art, representation, and content.

Enlarge

However, to push beyond simply identifying this problem, asking what can be learned from the case study of this group of artists is equally important, and whether there is still something to be salvaged from a DIY mentality. Moving beyond simply looking at communications technology and industry as an instrumentalizing force, what possibilities are opened up when these technologies are seen as relying upon the use and input from individuals and groups, as opposed to just a pre-existing infrastructure which constricts and controls? There is something to be gained from examining the success of the post-internet movement, its ability to organize and utilize its surroundings -both offline and online- to carve out a space for itself.

What the post-internet artists managed to do was create a movement in a fragmented and isolationist world by recognizing their capacity to act upon socio-technical networks. In the current crafting of their audiences, these DIY initiatives continue to cultivate a passive following – fluidly merging with the easy, consumption mode of scrolling and liking. However, as actors themselves, they are very pro-active in fostering their own network, which leads to the question of whether this active stance could be harnessed to form a non-conservative network formation. There are numerous benefits which communications technology enables, including mobility, increased proximity to groups with similar interests, decentralized organization, real-time feedback and communication, and many more. If this realization could be moved towards a non-conservative networked movement, then it carries real potential for enacting positive change. This requires the acknowledgement that, to quote Geert Lovink, ‘if networks are here to stay, we must take them seriously and realize their shape.’

As these kinds of networked environments begin to embed themselves in cultural practice, they must be examined critically for what kinds of politics and content they support, and what is left on the side. What is needed next is to understand that the capacity also exists, and indeed must be demanded, for mutations in this very same structure that alter the conditions art currently inhabits, and to develop effective strategies to deal with the violence and inequalities of capital as it exists today, and into the future.

Robin Lynch is an independent writer, scholar, and curator from Canada. She is an Art History and Communications Phd student at Mcgill University, Montreal, Canada and she recently graduated with her MA from the Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, NY. Robin was a Pendaflex Research Fellow at Henie Onstad Kunstsenter, Norway, where she has been researching and writing on the early electronic arts and internet art show, Electra 1996. Lynch was selected to be a Curatorial Fellow for artist run centre 221A Vancouver, Canada for 2015-2016. Kathleen Ditzig and Robin Lynch are the co-founders of offshoreart.co, a research platform investigating the role of finance, creative cities, and mobility in art. As part of this research, Lynch was recently the Curator in residence at Grey Projects, Singapore for February and March 2016.

Bibliography

Avanessian, Armen & Suhail Malik, ‘The Speculative Time-Complex’, Dis Magazine, 12 March 2016.

Boltanski, Luc and Eve Chiapello. The New Spirit of Capitalism. Trans. Gregory Elliot. London: Verso, 2005.

Bourriaud, Nicholas. Relational Aesthetics. France: Les Presse Du Reel, 1998.

Corbett, Rachel, ‘How Amalia Ulman Became an Instagram Celebrity’, Vulture, 18 December 2014.

DIS, DIS Own.

Droitcoeur, Brian. ‘The Perils of Post-Internet Art’, Art in America, 30 October 2014.

Durbin, Andrew. ‘We Don’t Need A Dislike Function: Post-Internet, Social Media, and Net Optimism’, Mousse Magazine.

Florida, Richard. The Rise of the Creative Class, Revisited. New York: Basic Books, 2012.

Lovink, Geert. Networks Without a Cause: A Critique of Social Media. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2011.

Luhmann, Niklas. Risk: A Sociological Theory. Trans. Rhodes Barrett. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers, 2008.

Manovich, Lev. Software Takes Command. Creative Commons License, Softbook, version 20 November 2008.

Pariser, Eli. The Filter Bubble: How the New Personalized Web Is Changing what We Read and how We Think. Penguin Books, 2012.

Quaranta, Domenico, Parker Ito and Artie Vierkant. ‘I like to Direct the Experience of Documentation: A Conversation between Artie Vierkant and Parker Ito’, Face to Face, Art Pulse.

Reeves, Elspeth, ‘The Secret Lives of Tumblr Teens’, New Republic, 17 February 2016.

Reylea, Lane. Your Everyday Art World. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2014.

Robinson, Walter. ‘Flipping and the Rise of Zombie Formalism’, Artspace, 3 April 2014.

Rogers, Richard. Digital Methods. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2014.

Sanchez, Michael. ‘2011: Art and Transmission’, Artforum, Summer 2013.

Siddons, Edward, ‘What’s Happening to Internet Art?’, Vice, 23 February 2016.

Troemel, Brad. ‘FREE ART’, I Would Like To Answer Your Questions, But The Truth Is I Just Don’t Know, Fine Arts Student Alliance, 11 February 2011, Concordia University, Montreal, Canada.

Troemel, Brad. Peer Pressure: Essays on the Internet by an Artist on the Internet, Lulu.com, 2011.

Troemel, Brad. ‘The Accidental Audience’, The New Inquiry, 14 March 2013.

Varadi, Keith J., Jesse Stecklow, and Spencer Longo. ‘An Introduction to The Jogging’, MOCA TV, 17 June 2014, The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.

Vierkant, Artie. ‘The Image Object Post-Internet’, 2010.