‘Weeks ago I saw an older woman crying outside my office building as I was walking in. She was alone, and I worried she needed help. I was afraid to ask, but I set my fears aside and walked up to her. She appreciated my gesture, but said she would be fine and her husband would be along soon. With emotion enabled (Augmented Reality), I could have had far more details to help me through the situation. It would have helped me know if I should approach her. It would have also let me know how she truly felt about my talking to her.’

This is how Forest Handford, a software developer, outlines his ideal future for a technology that has emerged over the past years. It is known as emotion analysis software, emotion detection, emotion recognition or emotion analytics. One day, Hartford hopes, the software will aid in understanding the other’s genuine, sincere, yet unspoken feelings (‘how she truly felt’). Technology will guide us through a landscape of emotions, like satellite navigation technologies guide us to destinations unknown to us: we blindly trust the route that is plotted out for us. But in a world of digitized emotions, what does it mean to feel 63% surprised and 54% joyful?

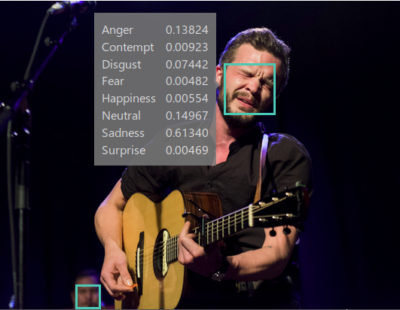

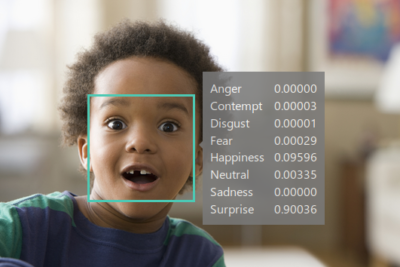

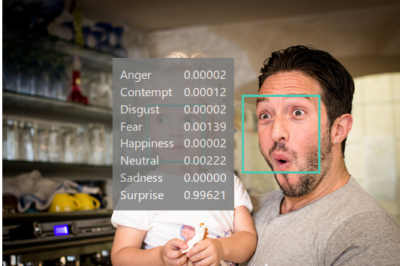

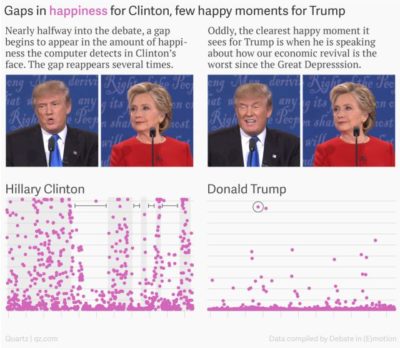

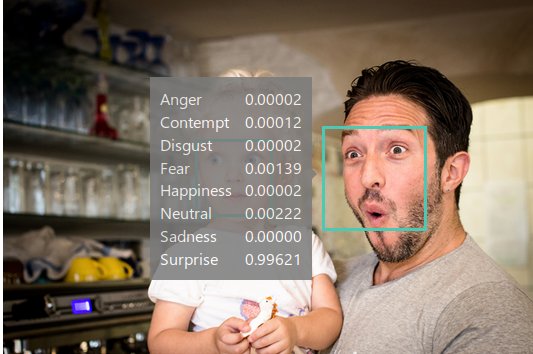

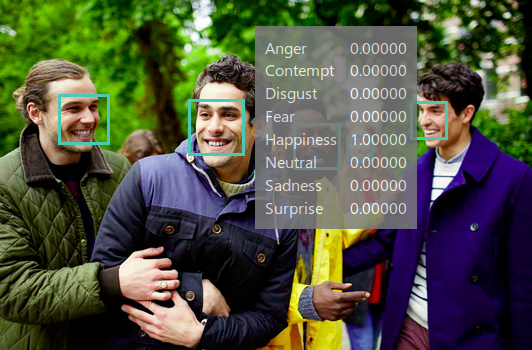

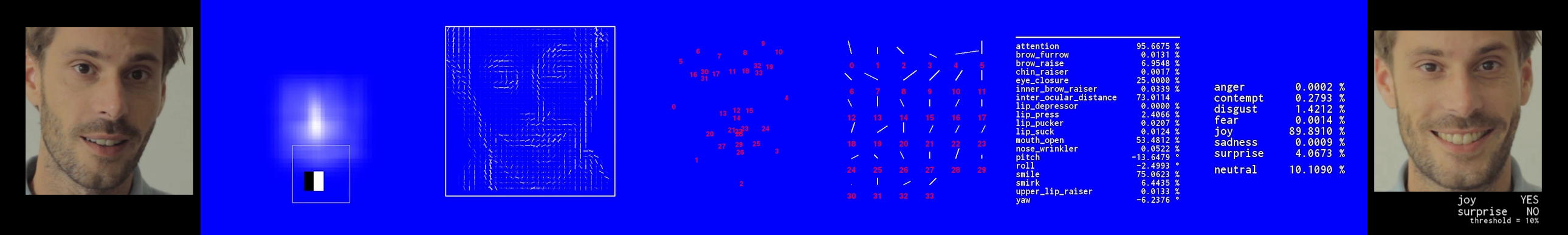

Demo images from Microsoft Cognitive Services’ Emotion API

Handford works in a field that has emerged at the intersection of computer science and psychology. Building tools to translate facial expressions, which have been captured using a camera, into quantified parameters, enabling comparisons and statistics. Multimillion dollar investments are made to foster a technology which is believed to facilitate new forms of human interaction, providing ‘objective and real-time, subconscious feedback’ on what ‘people really feel’ by using man’s ‘best window into the brain’. In certain academic fields the expectations rise high: in a conversation I had with Theo Gevers, professor Computer Vision and co-founder of SightCorp, he dubbed emotion analysis software to be the first step towards a morality aware artificial intelligence.

Affectiva, Emotient (now acquired by Apple), Microsoft Cognitive Services, Real Eyes, Eyeris EmoVu, Lightwave and SightCorp are some of the companies developing and using the software, living up to these high expectations.

Despite the faith in the capabilities of the technology, there are some fundamental assumptions underlying it that undermine its status as an objective entity. In what follows I will therefore expand on the goals of these software companies, revealing a paradox in the desire to measure and objectify a person’s mental state. Note that it are not the technological methods (such as machine learning algorithms) in and of themselves that I will discuss in this article; what I want to focus on here are the ways in which these methods are employed and promoted. Nevertheless, as I will show, the story of emotion analysis software can serve as a case-study for claims that are common in a broader big data narrative: that the use of massive data analysis could create an extra-human, objective perspective on the human condition. A claim I believe is flawed.

Measuring e-motions

Emotion analysis software started off as a technology targeted at people on the autistic spectrum, it seems however to have shifted to a primarily financial narrative:

‘Deep insight into consumers’ unfiltered and unbiased emotional reactions to digital content is the ideal way to judge your content’s likability, its effectiveness, and its virality potential.’ Affectiva

‘Emotions drive spending.’ Emotient

‘The more people feel, the more they spend. Research has firmly established that emotional content is the key to successful media and business results. Intangible ‘emotions’ translate into concrete social activity, brand awareness, and profit.’ RealEyes

Apparently, the fight over the consumer’s attention is so urgent and the importance of emotions so apparent, that many emotion analysis products are framed as tools to objectively map these ‘intangible’ mental states. Nowadays, the software is available for all sorts of devices such as laptops, phones, cars, televisions, wearables and even billboards. The Amsterdam based SightCorp for example, has introduced billboards at Schiphol Airport that keep track of the responses of passers-by, so advertisers can ‘optimize’ their advertisements for maximum attention. Most other companies in the field offer similar ways to measure responses to video advertisements.

Often, they also provide access to their emotion analysis algorithms for other software developers (by means of an Application Program Interface (API) or Software Development Kit (SDK)), which means other applications for the technology are emerging fast. For example, companies such as Clearwater and HireVue use emotion analysis software to compress recruitment processes – cutting back on relatively expensive job interviews. Another example can be found in an interview with Rana El Kaliouby, founder of Affectiva. She describes a project in which the company would work with live footage from video surveillance cameras (CCTV). Their technology would be added onto an existing camera infrastructure to measure the emotional wellness of various neighborhoods. Other companies, such as Sightcorp, suggest the use of emotion analysis software in surveillance systems as well.

Some people in the industry seem to be aware of a fragile balance between the attempt to do good and arming an Orwellian Thought Police. That is the reason, for example, why SightCorp doesn’t take on any military oriented contracts. Nevertheless, it is not solely a governmental Big Brother who likes to monitor: when one considers that many ‘smart’ televisions already send information obtained through the internal microphone and webcam to their manufacturers, the step to include emotion data seems small. Most companies developing e-motion software let the ideal of a life and society optimized for wellness prevail over their fears:

‘I do believe that if we have information about your emotional experiences we can help you be in a more positive mood and influence your wellness.’ Rana El Kaliouby, founder of Affectiva

According to the industry, measuring what makes people happy or sad empowers them to change their lifestyles and be in a more ‘positive’ mood. However, for a Caring Little Sister, this positive lifestyle can not be seen without commercial benefits, so certain moods could even lead to some sort of rewards, as El Kaliouby suggests: ‘Kleenex can send you a coupon – I don’t know – when you get over a sad moment.’

I'm feeling confuzzled

When attempting to understand these claims, we first need to know what the software measures. Each company in the field provides different software, yet feature sets vary only slightly. In order to theoretically account for an objective analysis of something generally seen as so ambiguous, almost all existing implementations are based on the same psychological model of emotions. When detecting a face in the image, the software translates facial expressions into seven numerical parameters, analogous to the seven pan-culturally recognized expressions of emotion as described by Paul Ekman: anger, contempt, disgust, fear, joy, sadness and surprise.

Enlarge

Ekman, a psychologist who is also known for his participation in the TV series Lie to Me and named by TIME Magazine as one of the 100 most influential people in the world, based his model on Darwin, who stated that expressions of emotion are culturally universal because they are grounded in an evolutionary process. He differentiated emotions from cultural dependent gestures. Nevertheless, the choice for Ekman’s model of seven emotions is not as indisputable as its omnipresence in the various tools might suggest.

Within scientific psychological discourse, there is no consensus on whether emotions and expressions of emotion are indeed evolutionary embedded in human nature, or purely culturally learned. Generally however, psychologists see it as being both: such expressions have an evolutionary basis but are highly influenced by cultural doctrine. From that perspective, explains psychologist Ursula Hess, the seven basic emotions can best be compared with a kid drawing a car: everyone will recognize it as a car, however, nowhere in real-life will one encounter a car looking like that. It is prototypical. Similarly, most people will categorize Ekman’s prototypical emotions in the same manner, but that does not imply that they are enacted in that exact same way in real life situations. Expressions of emotion (even sincere onces!) are generally considered to be shaped not only by a single state of mind, but by a rich context, including culture, the activity being undertaken, the mood one is in and a personal variation in physique and style.

The ambiguity of expressions is often ignored by developers when working with Ekman’s theory. I once was at a research presentation where the presenter showed an image of a face, asking the audience to guess which emotion was being expressed. The audience tried: ‘Anger!’, ‘Disgust!’, ‘Madness!’, ‘Annoyance!’ To which the presenter replied ‘no, this is clearly disgust.’ Not allowing for the multiplicity of interpretations to challenge her own rigid interpretation of the image.

Although the claim of intercultural universality of Ekman’s model is attractive when deploying software on a global scale: high esteemed companies, including Affectiva, Microsoft and Apple (Emotient), all of them base their software on a theory that is generally considered not to be suitable for real life situations.

The Kuleshov Effect

An example of the ambiguity of facial expression can be found in the Kuleshov Effect: at the beginning of the 20th century filmmaker Lev Kuleshov did an experiment for which he edited three video sequences. Each sequence showed the same ‘neutral’ face of a man, followed by the image of a dead man, a plate of soup or a woman (see the video). When these sequences were shown, the audience ‘raved about the acting’, believing the man who ‘looked’ at the dead man, the soup or the woman, was either expressing grief, hunger or desire.

Although an algorithm might classify the still face in Kuleshov’s experiment seemingly correct as ‘neutral’, when we consider the context in which the man is supposed to be – whether he is looking at a plate of food or a girl in a casket – one could argue this classification is just as inaccurate as a human projecting a contextualized feeling on the man’s expression.

Enlarge

Kuleshov’s editing experiment demonstrates that humans interpret facial expressions based on context. It renders the premise of emotion analysis software – a tool analyzing a person’s emotions solely based on facial expressions – questionable.

Moreover, the context in which emotions are expressed does not only affect how they are read; it also influences how people express their feelings, as is (remarkably enough) emphasized by Paul Ekman, who recorded American and Japanese subjects watching films depicting facial surgery. When watching alone, subjects from both groups showed similar responses. However, when watching the film in groups, the expressions differed.

‘We broadcast emotion to the world; sometimes that broadcast is an expression of our internal state and other times it is contrived in order to fulfill (sic) social expectations.’ Eric Shous

Contrary to the assumptions of current implementations of emotion analysis, such social pressure is also present when one is alone behind a computer, for example watching video content. As Byron Reeves and Clifford Nass show, despite computers being asocial objects and us having no reason to hide our emotions when using them, our ‘interactions with computers, television, and new media are fundamentally social and natural, just like interactions in real life’.

Another example: consider a musician playing, he is immersed in his own musical world. When one would judge his mental state merely by his face, one might think he is in a state of sadness or disgust. However, the audience, whipped up by the music, ‘knows’ he must (also) feel delighted. Like with Kuleshov’s experiment, it is often this projection of a subjective experience onto somebody else that enables one to read the other’s face. How can a computer project emotions? Even when it would, to some extent, take context into consideration, there could be various ‘options’ for what the subject is experiencing. Not everybody enjoys the same music, many might feel the musician is overly dramatic.

These examples of mislabeling may seem an easy critique of the technology. Some might suggest these are issues that can and will be tackled in future releases of the software, for example by making the software automatically tune towards a specific individual, or by taking some contextual parameters into consideration. I would argue however, that these errors are fundamental to the procedure and can therefore not be solved by making more elaborate calculations. Central to this is the conceptualisation of emotion.

Emotion as information

The attempt to computerize the recognition of emotions can be traced back to the MIT Media Lab where Rosalind Picard worked with Rana El Kaliouby in a research group on Affective Computing: a field of research that covers ‘computing that relates to, arises from, or deliberately influences emotion or other affective phenomena.’

With affective computing, emotions are digitized: they are considered as information. Emotions are thus treated analogously to Claude Shannon’s theory of information: there is a sender expressing an emotion, and a receiver interpreting the signal coming from a noisy medium. In this analogy, the success of the system can only be determined by identifying a correct, discrete, emotion in both the sender and receiver.

However, suggesting that a system has the ability to determine inner feelings from the surface, blurs the distinction between a system that describes behavior – one’s facial expression – and one that would describe a person’s inner, mental state. It blurs the measurable representation (the facial expression) with the underlying thing (the feeling).

Douglas Hofstadter, professor of cognitive science, illustrates this issue in Gödel, Escher, Bach when he discusses how a computer would understand the crying of a little girl: ‘…even if (a program) ‘understands’ in some intellectual sense what has been said, it will never really understand, until it, too, has cried and cried. And when will a computer do that?’ Is it then not true that, despite emotion recognition software being promoted as being able to ‘understand’ emotions, it will never be able to do that in a way that humans do? It can only measure and feign behavioral patterns. The ‘understanding’ only exists in the mind of the (human) user of the software.

According to Kirsten Boehner, researcher at Cornell University, the prominence in Affective Computing of an individually experienced yet measurable approach to emotion is explained by a ‘masculine, physically grounded’ ideal of science:

‘during the process of becoming ‘studiable’ the definition of emotion has been altered to fit a particular conception of what science ought to be: rational, well-defined, and culturally universal. (…) emotion is not thought of as biological, measurable, and objectively present because scientists found it to exist in the world that way, but because 19th-century scientists could not imagine studying it scientifically any other way.’ Kirsten Boehner

Even though emotion is traditionally considered to be opposed to rational cognition, it has been redefined in order to fit a cognitive, scientific approach of study. In this process, the aspects of emotions that are not clearly delineated were left out of the discussion. Affective computing – and with it digital emotion recognition – is following a similar path: even though the digitization of emotions is often presented as a more humanistic approach to the highly cognitive computer sciences, it, according to Boehner, ‘reproduces the very conceptual foundations that it aims to radicalize’.

Some might suggest using other computer algorithms can bypass this problem: the computer should not be instructed to detect seven predefined classes, but should by itself cluster similar expressions based on the gathered data – in technical terms: unsupervised rather than supervised machine learning algorithms should be used. Such an algorithm would value human interactions in a way that is not only unprecedented but most likely also incomprehensible by humans; it might even give rise to patterns humans are currently unaware of. However, in order for the measurements to be usable by humans, the measurements need to be translated into human language. Again, one arrives at the point of interpretation by a human agent, who will inevitably contaminate it with personal experiences and perceptions. Therefore, even in an algorithmic process, it cannot be ignored that the human evaluators and users of the software play a role in creating the emotions they are studying.

Hysterical detection

I would like to problematize this physically grounded approach to emotion, which side steps the human evaluator, by drawing a historical parallel. Emotion, as formally defined by the American Psychological Association and used in Affective Computing, is a broad and seemingly all-encompassing concept, which includes the unconscious and the conscious, internal bodily responses and facial expressions:

‘Emotion A complex pattern of changes, including physiological arousal, feelings, cognitive processes, and behavioral reactions, made in response to a situation perceived to be personally significant.’

It is a definition that seems to derive from the everyday use of the word and which is widely applied by psychologists in their day-to-day work. Nevertheless, when trying to quantify this concept, it could be exactly the extensiveness of the definition in which its danger lurks.

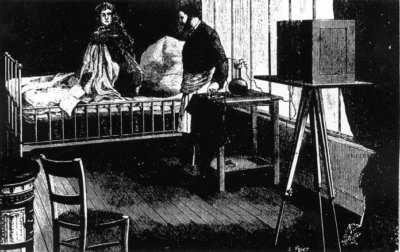

Enlarge

In his book The Invention of Hysteria, George Didi-Huberman elaborates on how research into hysteria became a formalized discourse. When in the 19th century Jean-Martin Charcot started to empirically study hysteria, it had always been seen as a female mental disorder. Despite endless observations of patients, no clear cause for the illness was found. However, rather than reconsidering the illness itself, the formal definition of hysteria became broad and all-inclusive. There were classifications, but they were more or less classifications of the unknown. In order to substantiate these classifications, Charcot and his fellow doctors required a massive set of data to work from and exhaustive descriptions of ‘states of the body’ became the norm. The patients’ bodies were no longer presentations of an individual, but rather representations of an illness.

Photography, a new invention in those days, was seen as the answer to the desire for an objective way of registering the symptoms of the illness. Seemingly substantiating the research being done, the immense documentation in text and images was not neutral though: the observers sought for specific anomalies, and by prioritizing the deviant, they effectively rewarded and encouraged such behavior in their patients. Nowadays hysteria is not considered a distinguishable mental illness anymore and the feminine aspect of it is merely considered sexist. In hindsight, Didi-Huberman calls hysteria the ‘neurosis of an immense discursive apparatus’. A neurosis that required endless descriptions of patients and strict procedures in order to justify the treatments of the patients. The massive administration, focused on capturing hysteria, effectively clouded the illness. As Didi-Huberman points out, the ‘ideal of the exhaustive description’ of hysteria might have grown from the hope that seeing can be foreseeing.

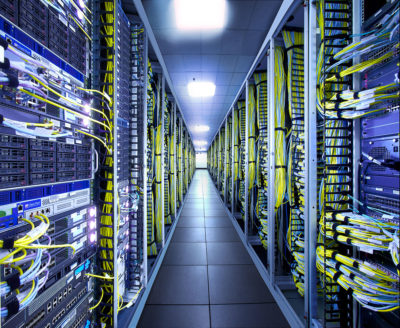

Poyet Photography at the Salpêtrière side by side with a contemporary data center

Similarly, the many – sometimes overlapping, sometimes contradictory – accounts of what ‘emotion’ entails, demonstrate the ambiguity of the term. Any definition of the term seems under heavy influence of its indefinite informal use. These definitions might work for psychologists in their day-to-day interactions with patients. When trying to quantify it however, with its definition so broad and vague – encapsulating how we feel, look, and sound – ‘emotion’ seems to be a concept that is susceptible for such a ‘neurosis’ as well. By presenting emotion analysis software as a clearly defined technology, which is capable of ‘accurate’ measurements, a joint venture of psychology, computer sciences and marketing skims over the ambiguity of the concept ‘emotion’.

Enlarge

It is not a far stretch to compare the immense data gathered by companies such as Affectiva, which claims to have indexed almost 4 million faces, to the data gathered in the 19th century. In both cases a new, supposedly objective, technology was used to validate the classification procedure. In both cases, with strict procedures for prediction, seeing supposedly becomes foreseeing.

Key here is not only that the classification procedure in and of itself is flawed; the main concern is that the definitions that delineate the technology are flawed. As there seems not to be a clear definition of ‘emotion’, how can one know what is being measured by emotion analysis tools? Like with the case of hysteria, it is merely the connotation of ‘emotion’ in everyday language that gives the illusion of knowing what is being quantified.

Registering stereotypes

When being aware of contemporary marketing, it comes as no surprise that on their websites companies such as Microsoft and Affectiva pass by these discussions and present their software as a definitive answer. But if indeed emotions are not concrete, delineated experiences, how can these software products, which use such a coarse, seven-term language, be so successfully marketed? I would suggest it is precisely this coarse language that benefits the marketing of emotion analysis software.

The demo images that are used by Microsoft Cognitive Services are stock photographs.

To showcase their software, companies present photographs of strong facial expressions, such as those at the beginning of this article, to demonstrate successful classifications of emotions. As (almost) everyone will recognize the link between the prototypical facial expression and the emotion terminology, they assume the measurement is accurate. However, once we recognize these images as stock photographs, we will realize the people in these images enact a specific feeling. It is the feeling they present that is picked up by the software, not the feeling they might have had at the moment the picture was taken!

Emotion recognition technology is often (directly or indirectly) linked to Artificial Intelligence. Examples are from the websites of Affectiva, Emovu and Microsoft Cognitive Services.

Also, in their marketing, emotion detection algorithms are linked to popular yet loosely defined concepts such as artificial intelligence, which deliberately obfuscates and mystifies the technology. This seems to serve only one goal: spectacle. As Guy Debord describes, in the spectacle it is not about ‘being’ but about ‘appearing’ – there is a separation of reality and image. In the spectacle, that which is fluid is being presented as something rigid, as something delineated, just as we saw happen in the case of hysteria. Similarly, it is the spectacle that obscures how feelings of people are not addressed or measured by the software at all.

In turn, it is exactly the supposed rigidity of concepts that normalizes, validates, the spectacle itself! Through the process of showcasing the functionality of the software on a limited set of stereotypical images (i.e. stock footage of smiling people) the particular associations with the prototypical seven emotions are reinforced. In the end, these images merely support the claim that concepts such as ‘anger’ and ‘happiness’ are clearly delineated, and thus measurable phenomena.

In other words, the promotion of emotion analysis technology normalizes concepts such as ‘anger’, ‘sadness’ and ‘contempt’. Through that process of normalization, the position of the software as a tool that is able to measure these concepts is strengthened. Rather than giving new insights into how humans interact, these systems reinforce an existing preconception of what emotions are. For that reason, the technology ultimately provides a guideline for humans to express themselves.

Chief Emotion Officer

The relevance of this normalization becomes apparent when we go back to the applications of emotion recognition software. It seems that the software’s narrative of wellness and performance aligns with the vision of what is known as the Quantified Self movement: a term coined by two editors of Wired Magazine, when advocating the use of technology to measure an individual’s behavior in order to maximize both its ‘performance’ and ‘wellness’ in a statistical manner. Thousands of apps and gadgets are created (and sold) to aid this constant self-optimization. The list includes tools for sleep pattern analysis, step counting and food consumption tracking. And now: emotion analysis.

In the process of self-optimization, people engage in an interactive relationship with their personal measurement data. This relationship is often designed to be playful, yet it can, in the words of Finish researcher Minna Ruckenstein, ‘profoundly change ways in which people reflect on themselves, others and their daily lives.’ She did an experiment in which people kept track of their heart rate, which is commonly linked to stress levels. The subjects could see their data on regular intervals. Rather than just taking the data as a given, people started a ‘conversation’ with it. They changed their opinion of their day based on the data, or they started doubting the data because of their experience of the day.

When seen in the light of emotion analysis, these extensive (self-)evaluations frame expressing emotion analogous to performance: as we also saw in the example of the Kleenex coupon, in the constant strive for wellness the production of emotion becomes a goal. What is analyzed is not the emotion itself, but the effectiveness with which emotions can be induced and controlled.

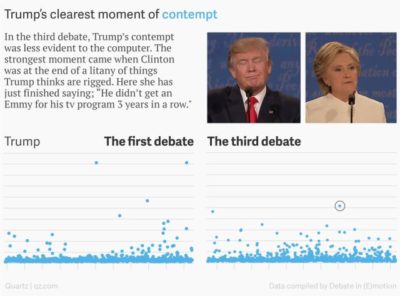

Examining emotion analysis software from this perspective brings a paradox to light. One of the central objectives for emotion technology is to measure a ‘sincere’ and ‘unbiased’ response; however, how will that still be possible considering that emotion analysis indeed influences behavior? For example, at recent debates between US presidential candidates Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, software was used to ‘determine emotional intelligence and sentiment’ of the candidates, as this should provide a ‘rare glimpse into what they illustrated beyond their frustrations and political platitudes’ – whatever that may mean. For now this might still be an incidental gadget to make a quantified, ‘exact’, comparison between the candidates. However, it might change the way in which many public figures operate: there has been research that correlates CEO’s facial expressions to the market value of their companies. A positive correlation was found between measured expressions of fear, anger and disgust and the company’s market value. Being aware of such measurements, it is not so hard to imagine that CEO’s and other public figures will train their behavior to reflect a (more) positive situation.

This is not a far stretch. HireVue is a company that uses Affectiva’s emotion analysis software together with other analytic techniques to evaluate job candidates. At the same time they use their technology to train people to present themselves for when they are being analyzed by this software. So software is employed to analyze people, while simultaneously people are trained to perform by the rules this software imposes! As with the case of hysteria, a procedure that sets out to make the Other more transparent, achieves the opposite: emotion analysis practices make the face aneven more trained facade.

Alienating sincerity

‘...measurement of a person’s mental state is unlikely to be exact. After all, even people find it hard.’ Peter Robinson and Rana El Kaliouby

Surely, the premise of facial emotion analysis has promising aspects – a bit more empathy in the world would do no harm. However, by examining the discourse surrounding these technologies we can only conclude that the models elementary to this technology are speculative and put into question the validity of the whole procedure.

The current scientific debate primarily focuses on optimization of the technology’s performance, whereas the public discourse is fueled by marketing applications and dreams of frictionless interaction, in both human-to-human as well as human-to-computer contact. The initial research into autism seems almost completely neglected in favor of advertisement applications. Not only is that a commercially more attractive market, it is also a field that requires less scientific substantiation.

It is unclear what exactly concepts such as ‘emotion’, ‘anger’, ‘contempt’, ‘disgust’, ‘fear’, ‘joy’, ‘sadness’ and ‘surprise’ entail. What is being measured thus remains unclear. What do these coarse parameters say about the subjects of analyses, about them as human beings? The subjective human input, ambiguous terminology and highly selective use of psychological theory are covered up under layers of extensive data collection, administration and optimization; positioning emotion analysis software as a valid, objective measurement tool. The question I asked at the start was, what then does it mean to feel 63% surprised and 54% joyful?

The numbers, rather than showing the intensity of an emotion, reflect the statistical similarity with a prototypical expression, which is now established as a desired way of showing a certain feeling—whether true or feigned. When applying the software as a tool for training, these facial expressions are rather performances, or representations, than reality: they become deliberate mediations instead of expressions. Because of this I would argue, in line with Guy Debord, that these procedures in the long run might alienate subjects further from themselves, rather than improving their wellness.

Handford’s anecdote with which I started this text, illustrates how society’s constant drive to improve personal performance has lead to a desire for a technology that claims to measure, and thereby control, something which we experience as hard to grasp. Paradoxically, emotion analysis technology appeals to both a desire for sincerity in a mediated society, and to a desire to present (to market) something or someone as sincere. Assuming that the longing for sincerity in a mediated society rises from a sense of alienation and uncertainty, reveals the irony of the situation; the provided ‘solution’ only further alienates the subject.

What is problematic is not so much the attempt to capture patterns in human expressions per se, or in human behavior in general; what is problematic are the words used to describe and justify this procedure. The focus on algorithmic performance and statistical accuracy obscures that making assumptions is inevitable when quantifying broad humanistic concepts. When considering Didi-Hubermans writing on hysteria, it is easy to draw parallels and see how a narrative is being constructed that invents and substantiates itself. The juxtaposition of emotion analysis software with the historical case of hysteria makes apparent what risks the transformation of broad humanistic concepts into a positivist framework carry in them.

Enlarge

A graph showing the measurements of various emotions by IBM Watson in 10 texts.

Such a transformation of concepts happens more often in Big Data practices, whether it is emotion analysis, text mining or self-monitoring. However, due to the solution driven nature of programming, this transformation happens not always with much care for the ambiguity of the original concepts. For example, IBM has a product-line with various algorithms named Watson; recently they added a new algorithm that ranks texts on joy, fear, sadness, disgust and anger. Out of the desire to build software that works on a global scale, a list of emotions that is derived from a (already problematic) theory of cultural universal facial expressions is applied to analyze text.

There are plans to apply automated emotion analysis to footage of surveillance cameras; already the technology is used (without the subject’s consent) on a massive scale through e.g. billboards. Some may find comfort in the fact that the market gets ahead of itself and makes claims that are untenable. It would be much more Orwellian if emotion analysis actually produced sensible results. Nevertheless, we should take care that this technology and its results will not be treated as if they do so.

However, the most important conclusion is that such complex algorithms, which are often seen as obscure ‘black boxes’, can be inquired without getting into the technicalities of the procedures. We should constantly break open the facade of their supposed objectivity and question the narrative of ‘wellness’ by discussing the technology’s fundamental assumptions. In that way we can encourage a critical position against the dominance of the positivist’s simplified worldview.

Enlarge

Combining his backgrounds in filmmaking, programming and media design, Ruben van de Ven (NL) challenges alleged objective practices. He is intrigued by the intersection of highly cognitive procedures and ambiguous experiences. He graduated at the Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam where he started his investigation into computational quantification and categorization of emotions, which he now continues as a member of Human Index. This INC Longform originated in his Piet Zwart Institute graduation thesis. His recent artistic works on this topic include the algorithmic video works Choose How You Feel; You Have Seven Options and Eye Without A Face, as well as the video-game-artwork Emotion Hero.

References

Boehner, Kirsten, Rogério DePaula, Paul Dourish, and Phoebe Sengers. 2007. ‘How Emotion Is Made and Measured.’ International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 65 (4). Elsevier: 275-91.

Debord, Guy. (1967) 2014. Society of the Spectacle. Translated by Ken Knabb. Bureau of Public Secrets.

Didi-Huberman, Georges. (1982) 2003. Invention of Hysteria: Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière. Translated by Alisa Hartz. Mit Press.

Khatchadourian, Raffi. 2015. ‘We Know How You Feel.’ The New Yorker, no. 19 (January). http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/01/19/know-feel.

Ruckenstein, Minna. 2014. ‘Visualized and Interacted Life: Personal Analytics and Engagements with Data Doubles.’ Societies 4 (1). Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute: 68-84.