Fic-ctio-cra-cy /ˈfɪkʃ(ə)krəsi/ n. pl. – cies. 1. Political regime that, implicitly or explicitly, considers the distinction between fact and fiction irrelevant. 2. A political or social unit that has such regime. 3. The principles of word-building and transmedia storytelling applied to politics and journalism. 4. The title of this longform. [French fictiocracie, from Late Latin fictiocratia]

In his 2017 book – adapted in a longform for the Atlantic – writer Kurt Andersen recounts the 500-year history of the troublesome relationship between the United States of America and the notion of reality. Andersen’s thesis is straightforward: Americans have always been prone to fantasies (mainly in fictions, religions and conspiracies) but never to the degree encountered in this time of fake news and post-truth politics. In this sense, the internet acted as catalyst, multiplying the impact of falsities and further blurring the boundary between fact and fiction. In conclusion, Andersen – ascribing himself to the shrinking ranks of a supposed reality-based America – calls for a ‘grassroots movement (...) that insists on distinguishing between the factually true and the blatantly false’.

This article explores an issue that is in close proximity with what Andersen describes. What I attempt to achieve is an understanding of so-called post-factuality as a form of ‘fictionality’. What is indeed ‘fictiocracy’ if not the political regime of Fantasyland? However, my approach is different in two fundamental ways. Firstly, Andersen is not particularly interested in the problem of representation per se. He doesn’t address the question of how media construct – rather than represent – reality. On the other hand, there’s a question that has always fueled my curiosity: how do we make sense of the relationship between any representational media and reality? It’s a question that goes far beyond fake news and post-truth politics, becoming ontological – given that we live our lives mainly through media. In this sense, in a time when media are to humans what water is to fish, media studies are almost a form of applied ontology. The second big difference between fictiocracy and Fantasyland is that the latter identifies a specific country while the former hints to a political style that has no fixed abode. Nevertheless, in the same way as they’re popularly defined as one of the world’s largest democracy, the United States are also a prominent fictiocracy – especially nowadays – and therefore an easy object of observation. For this reason, the essay focuses extensively on Trump’s presidency. Structure-wise, it is divided in three chapters:

- Trump Will not Be President

- Trump Is not Really Being President

- Trump Has not Been President

The obvious reference for the titles are the three controversial essays that French philosopher Jean Baudrillard published in Libération between January and March 1991. There, the ‘high priest of postmodernism’ laid out his analysis of the Gulf War as a ‘non-event’, a masquerade of war. Similarly, I will illustrate Trump’s presidency as a masquerade of politics, where the representation of the event precedes the actual event, generating what Baudrillard calls ‘hyperreality’. However, I will draw less on Baudrillard and postmodernism in general, than on theories from the field of fiction studies. In particular, what I propose is a systematic application of the principles of fictional world-building and transmedia storytelling to the real world, and in particular to politics and its amplifier, journalism.

On the one hand, there is journalism that lives at the same time bleak and bright. Trump’s election has been a defibrillator (Trump – bump) for journalism, refreshing its societal appeal. Digital subscriptions to major newspapers like The New York Times rocketed. Under the fire of fake stories, journalism questions its own identity. What is its mission? Why do readers, viewers and users consume news? Is it because they want to be informed or is journalism just another branch of entertainment?

At the same time, the Trump bump doesn’t seem likely to sustain a prolonged growth, let alone a serious business model. Advertising revenue is dwindling and while digital juggernauts such as Vice and Buzzfeed fail to hit their revenue targets, new hungry and dirty players appear at the block. Alt-right media outlets such as Breitbart and Infowars impose a radically different business model, one that has more to do with fiction than with news, as I will propose later on.

On the other hand, we have the latest trends in storytelling. Since media studies always crave new terms, digital media are now called ‘emerging media’. Even if they’re certainly emerging in popularity, these media are ‘immersing’ as far as their way of engagement is concerned. They take the audience and plunge it into the storyworld, be it literally – by way of VR headsets and tools for augmented reality – or narratively, thanks to world-building. Frank Rose described this logic in his 2011 media-bible The Art of Immersion.

If I had to pick an adjective to describe contemporary storytelling, it would certainly be ‘immersive’. Stories are not like flat horizons to be admired at a distance anymore but environments to be navigated and, even more simply, lived. This blurs the boundary between fiction and reality. But what kind of reality are we talking about? ‘Reality is a scarce resource’ wrote communication theorist James Carey a while ago, but nowadays it seems that reality comes in potentially infinite supply. VR, AR, MR and all other Rs promise to free us from the constraints of a single world-experience.

To a certain extent, this abundance of reality is a new phenomenon. Technology grants unprecedented affordances to build fictional worlds. The Marvel universe is only possible as a transmedia project that spins TV series and movies alike, Pokemon Go as a mobile app and Carne Y Arena by Inarritu as a VR installation. However, stories have always been about creating new realities. And this has always scared human beings. How will we understand when the story ends and life begins? For every new medium, conventions arise to solve this dilemma. Nowadays we’re perfectly at ease watching movies but when the Lumiere brothers projected the Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat in 1896, a sense of wonder and amazement likely pervaded the audience.

According to media scholar Janet Murray, virtual reality is still at the amazement stage. Until the medium develops stable conventions, VR films will strike us for their power of representation, the same way Plato was mesmerized by the power of representational art in the Phoedrus. Janet Murray also noticed that when a medium lacks conventions, it can be exploited to address bigger concerns and anxieties of the time. An example is the 1782 novel Les Liaisons Dangereuses by Choderlos de Laclos that used the form of the epistolary novel to discuss the decadence of the godless aristocracy in the fin de siècle. ‘Are these real letters?’ the readers of the time probably wondered. Closer to us, Orson Welles adopted the same strategy when he performed the radio drama The War of the Worlds on CBS in 1938. The audience believed to be listening to a factual report of an alien invasion and panicked. What was at stake was the public anxiety around the possibility of a global conflict. It doesn’t matter that the War of the Worlds social panic has a dubious status of authenticity. The creation of reality through media is after all what this all essay is about. Here, I try to do the same thing: I deploy fiction to understand the present and also to imagine alternatives to it.

Trump Will not Be President

Enlarge

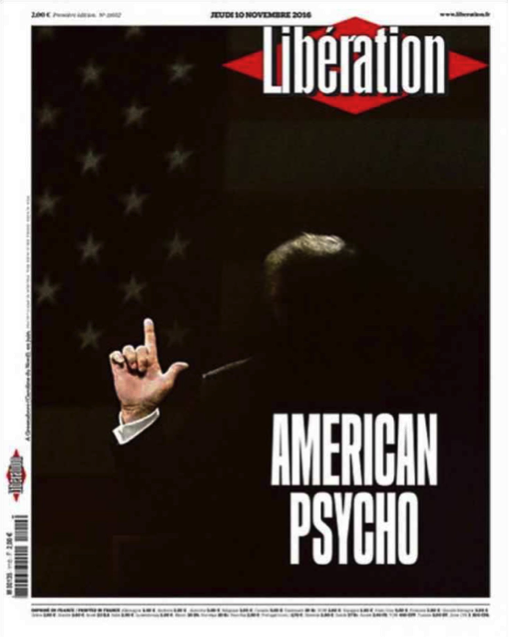

When Trump won the elections, the French newspaper Liberation proposed an impactful frontpage with the title ‘American Psycho’. It referenced the 1991 novel by American writer Bret Easton Ellis, which tells the story of Patrick Bateman, a 27 years old investment banker who divides his time equally between a lavish lifestyle and a double life as a rapist and serial killer. As a prototypical yuppie of the 80s, Patrick Bateman likes Phil Collins’ music, Oliver People’s glasses and… Donald Trump. Actually, Trump is nothing less than Bateman’s aspirational model. He even changes his mind about a pizza brand just because ‘Donnie’ – as the neighborly calls him – likes it. Trump, also due to bestselling books like The Art of the Deal, is a business celebrity and a trend setter already in the 80s, happy inhabitant of both the business world and the media landscape.

Enlarge

If we want to understand not just Donald Trump but also fictiocracy we need to start at the time of strawberry risotto and Tab cola, when it seemed utterly impossible that Trump – the casino magnate – would ever become president of the United States. Surely anyone who was asked about the likelihood of a Trump presidency would have exclaimed ‘Trump will never be president!’. Yet, the president at the time was Ronald Reagan, a former actor. It’s not by chance that his administration featured some characteristics ante-litteram of a fictiocratic regime. In all of this, journalism turns into a branch of Public Relations. British filmmaker Adam Curtis – never shy of grand illustrations – effectively narrated this epoch in his recent documentary Hypernormalisation. There, he describes how the Reagan administration pioneered perception management, spinning news that blurred fact and fiction with stories created to shock public imagination. It didn’t matter whether the stories were true or not; what was important was their narrative value and their ability to distract the public.

Thus, the roles of fictional storyteller and news journalist overlapped. In the words of Michael Deaver, White House Deputy Chief of Staff under Reagan: ‘It would be so good that they’d say "Boy this is going to make our news tonight". We became Hollywood producers.’ The practice – invented to ‘kick the Vietnam syndrome’ – escalated at the end of the 80s with the incumbent Gulf War that started to resemble a cable drama series, to the philosophical delight of Baudrillard.

The most melodramatic moment is probably the hoax pulled in 1991 by the Washington-based prestigious PR firm Hill & Knowlton. Hired by the Kuwaiti Royal Family and with the US government imprimatur, the firm set up an ‘astroturf’ movement to stir the American public opinion in favor of a military intervention against Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, that had invaded Kuwait a year before. ‘Astroturf’ is a brand of artificial turf playing surface and, in PR jargon, the expression denotes political movements sponsored by governments, institutions or corporations but presented as spontaneous, grassroots initiatives. In this case, ‘Citizens for a Free Kuwait’ was pitched as a group of Kuwaiti citizens, autonomously gathered out of their concern for the occupied homeland. In astroturfing, the dividing line between fiction and reality is inherently blurred given its deceptive premises and such a line becomes utterly non-existent when the activities of an astroturf movement are taken up by the press and fed to the ‘storytelling machine’ of news media. In this case, Hill & Knowlton started to produce so-called Video Release News (VRN): videos packaged as objective, journalistic reports whereas they were just sponsored content. Such videos were then distributed to television networks, eager (especially if they are small, local networks) to have alluring, free material at their disposal. Among the great wealth of Kuwait-related material that Hill & Knowlton spun in order to massage America’s public opinion on the possibility of a Gulf war, there is one that particularly resonates with my overall analysis and to which I will now turn my attention.

It’s the speech that a young girl called Nayirah gave in front of an American commission for human rights. The girl presented herself as a volunteer that witnessed how the Iraqi army looted Kuwaiti hospitals, stealing incubators and throwing babies on the cold floor to die. Conveniently filmed, the deposition was spread through several news TV channels and president George H. Bush himself publicly quoted the episode several times as a reason to invade Iraq by force of arms as soon as possible. As was demonstrated later on, the girl was the daughter of the Kuwaiti ambassador, coached by Hill & Knowlton to deliver a fake testimony. However, the debunking of the news (its fact-checking) didn’t make it less valuable in the thriving ‘economy of signs’ that the Gulf War sustained. In other words, Nayrah’s fake testimony highlights that in a regime of perception management – the older brother of fictiocracy – what matters is not the objective, real truth but how a fictional story is pitched. Politics is almost entirely consumed at the superficial level of signs and politicians need to play along and to perform a role.

Trump is the cultural hero of this age, a man ‘sprang from a Platonic conception of himself’ to paraphrase Scott Fitzgerald. It doesn’t matter if his business enterprises are on the verge of collapsing – as Curtis recounts in Hypernormalisation – what is important is to keep pretending, to keep performing, like Nayrah and a lot of other people at the time. As film critic Neal Gabler wrote for The New York Times: ‘In a famous commercial a few years back, a soap opera star announced, "I’m not a doctor but I play one on TV." Today, when it seems everyone is engaged in some sort of performance or another, that could serve as the nation’s motto. "I’m not a hero but I play one," says Oliver North. "I’m not a football star but I play one," says Brian Bosworth. "I’m not a journalist but I play one," says the local news anchor. "I’m not a President but I play one," says Ronald Reagan.’

That is the beginning of fictiocracy.

Trump Is not Really Being President

Jones, who loves to draw analogies to sci-fi classics like Dune and Star Wars, sees the 21st century as a kind of fanboy-fantasy landscape populated by three groups: a rebel alliance of liberty-loving patriots (his fans); masses of consumerist sheep (those who ignore him); and a sadistic elite (global bankers and their agents), forever tightening the screws on the imperiled remnants of human freedom Alexander Zaitchik, ‘Meet Alex Jones’, Rolling Stone

A long time ago, in a galaxy far right away, there existed Infowars, the transmedia outlet that the ‘prophet of paranoia’ Alex Jones founded in 1999 and that since then has been spinning an infinite amount of conspiracy theories. For many years Jones has been an eccentric figure; the ranting man of Richard Linklater’s Waking Life or the lunatic that infiltrates Bohemian Grove with journalist Jon Ronson. However, in December 2015, Donald Trump told Alex Jones that his reputation was ‘amazing’. Since then, it became clear that there was a strong cultural connection between Jones and Trump. Jones was not (just) a media oddball anymore.

Enlarge

Alex Jones and his Infowars are premium examples of successful journalism in a fictiocratic regime, because they systematically apply the principles of transmedia storytelling and fictional world-building to their reporting. Infowars relies on a wide range of media and formats, from its daily radio show to its YouTube channel (with over 2 million subscribers), from social media pages to PrisonPlanet.tv – a twin website of Infowars. Understanding Alex Jones’ media outlet from the unusual perspective of fictional transmedia storytelling allows us to make sense of it both on a commercial and a narrative (journalistic) level.

In the context of the crisis of journalism that I described, Infowars is paradoxically both a symptom of such crisis and a cure for it. It’s a symptom because of the infinite amount of conspiracy theories and fake news it proposes but it’s also a cure due to its innovative and successful business model that – relying on what media scholar Henry Jenkins calls the ‘extractability principle’ of transmedia storytelling – grants Alex Jones a constant stream of revenue.

But to make this point clearer, I first need to introduce the fictional world of Infowars, a dystopian narrative environment where nothing is what it seems and where what passes for reality is assumed to be like a veil that the elites have pulled before our eyes. Does it sound like The Matrix? Sure! And that’s because the Wachowski brothers’ sci-fi saga is a major source of inspiration for ‘the stocky Texan’ – as Jones is infallibly described at one point of all the journalistic portraits dedicated to him.

Enlarge

‘Are you living in the Matrix?’ asks a video posted on Infowars’ Facebook page. ‘Yes’ is the answer. We live in a fake reality created by transnational corporations, technological elites and corrupted politicians. ‘The answer to 1984 is 1776’ claims a tagline of the video with a double reference to George Orwell’s novel and to the year of independence of the United States. The spirit of ’76 remixed by Jones is a vague blend of conservatism, isolationism and libertarianism. Put simply: more guns for more people. The guns needed are both literal and metaphorical because – as an other tagline of the video admonishes – ‘there is a war on for your mind’.

It’s a serendipitous coincidence that Henry Jenkins dedicates the chapter of his book Convergence Culture that delves into ‘transmedia storytelling’ to The Matrix. In his analysis, Jenkins outlines seven principles: spreadability vs drillability, continuity vs multiplicity, immersion vs extractability, world-building, seriality, subjectivity and performance. The pairs are opposite concepts or ‘opposite vectors of cultural engagement’, as defined by Jason Mittell. All seven principles of transmedia storytelling are relevant for my discussion of Infowars and can help to make sense of the medium.

For example, the principle of ‘drillability’ which refers to a mode of ‘forensic fandom that encourages viewers to dig deeper’ is echoed by Jones’ frenzied invitations to never stop at the official version of actuality, to ‘join the resistance’ – as it goes in one Infowars’ tagline. For the sake of brevity, I focus here on the principles of transmedia storytelling that make my point about Infowars as clear as possible. In particular, I discuss the couple ‘immersion vs extractability’ and the notions of world-building and performance, tying the latter to what I identify as a salient feature of any model citizen under a fictiocratic regime.

Jenkins defined ‘immersion’ as ‘the ability of consumers to enter into fictional worlds’. As stated earlier, ‘immersion’ is probably the single most relevant term to analyze contemporary storytelling. The Infowars saga is certainly an immersive universe that relies on a hardcore fanbase that doesn’t cherry-pick single conspiracy theories in a mood of casual consumption, but rather requires a ‘take-it-all’ attitude, a radically different approach to the world. A perfect companion to ‘immersion’, ‘extractability’ is realized when ‘the fan takes aspects of the story away with them as resources to deploy in the spaces of their everyday life’. A good example might be ‘Los Pollos Hermanos’, the fictional fast-food chain of the TV series Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul. As it’s known, the production opened pop-up Los Pollos Hermanos restaurants worldwide in order to promote the series. There, the fan could enhance his narrative experience of Vince Gilligan’s universe by having a meal in a perfect reconstruction of the location so crucial to many plot developments of both series.

Enlarge

Infowars elevates the ‘extractability’ principle to a business model by incorporating in the website an immense online store that proposes a seemingly endless list of products needed to live what is termed an ‘Infowars life’. Aside from more conventional merchandise such as t-shirts and posters, we find more peculiar items like disaster-food supplies, gears to survive a hypothetical biological or nuclear emergency, water filtration systems (Jones claims that the government is poisoning the American population by adding fluoride to water), and tools that are meant to protect security and privacy like a ‘detracktor cell phone pouch’ or ‘tactical’ holsters for guns. But, above all, the Infowars online store is flooded with an enormous variety of dietary supplements that range from ‘Brain force plus’, an alleged ‘neural activator’, to the ‘Caveman true paleo formula’, a sixty dollars mix of cartilage, bone broth and ‘paleo ingredients’. Commercially, the online store is the main source of revenue for Infowars to the extent that rather than a media empire Alex Jones owns a ‘snake-oil empire’, as journalist Seth Brown argued in an article for The New York Magazine. In particular, Brown speculates that Jones might cash-in up to twenty-five millions of dollars per year just from dietary supplements. The online store also works as a narrative strategy because it gives its customers the opportunity to live the narrative of this world in first person, pretty much like Los Pollos Hermanos does for the Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul universe.

Enlarge

In this sense, Infowars is more an example of fictional world-building than of a traditional news organization. In a time when journalism is flailing to find a viable business model, Alex Jones proposes a disconcerting alternative: becoming a world. A fictional universe where the emphasis is not on the coherence and solidness of the plot itself but in the credibility and complexity of the environment where the story takes place.

To paraphrase Jenkins’ quote of an experienced screenwriter: in the past, an author had to pitch a story, later he had to pitch a character, and nowadays he has to pitch a world. Infowars follows the same logic proposing every day new conspiracy theories that ‘don’t add up’ narrative-wise but contribute to create its fictional world. A realm where 9/11 was an inside job, the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing was staged by the government and maybe Trump is not even the current president of the United States, replaced with a reptilian clone by the Illuminati. ‘Trump is not really being president!’ Jones might exclaim in the future, defending the current administration by potential accusations of inefficacy. In all of this, Alex Jones mixes journalism and performance art – as significantly proposed by his lawyers during a trial over the custody of his children.

Trump Has not Been President

We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality – judiciously, as you will – we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors… and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do. Karl Rove, George W. Bush Administration’s Deputy Chief of Staff

Infowars claims to be ‘the resistance’ but at the end it’s the Empire’s official bulletin. Who then are the real rebels in Fantasyland? How can a fictiocratic regime be overthrown? This section addresses these questions. In a way, it’s a practical field-guide to a semiotic coup d’etat. I will argue that, contrary to common belief, the myth of objective journalism cannot represent an answer to propaganda and misinformation. We need to tackle the issue from a different perspective. We need more, not less, misinformation. ‘Throw more wood in to smother the fire’, states the military Chinese essay Thirty-six Stratagems. Media art boasts a significant pedigree in this sense. In 1993, three years after Nayirah’s testimony, cultural critic Mark Dery published his article The Merry Pranksters and the Art of the Hoax, a seminal text in the tradition of culture jamming. In the article, Dery shows that media have always been creating reality. There has never been such thing as objective journalism. ‘You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the war’, news industry titan William R. Hearts famously declared (or did not, which would somehow prove my point). Media are manipulative by definition, almost ontologically.

Culture jamming is about not reporting but rather ‘remaking reality’. Jammers were a ragtag army that employed unconventional weapons like spoofs, pranks and hoaxes. Dery proposed self-styled conceptual artist Joey Skaggs as a prominent ambassador of the movement. Among many other quixotic endeavors, he notoriously placed a fake ad for a ‘dog brothel’ in the Village Voice in 1976. ABC even won an Emmy Award for a piece of serious reporting on the case. Fake news ante litteram.

In the following years, the tradition of culture jamming has been informing the incursions of many other media artists. In the Netherlands, the Tactical Media movement was particularly keen on this approach. Academically baptized by David Garcia and Geert Lovink, Tactical Media flourished in the final years of the 90s. The term ‘tactical’ refers to the distinction between tactics and strategies as elaborated by French Jesuit Michel de Certau in his book The Practice of Everyday Life. Differently from strategies, tactics shy away from grand revolutionary perspectives emphasizing the relevance of individual acts of daily resistance or of what ‘is doable now’. Following this tenet, Tactical Media favored rapid actions that jammed the operations of mainstream media.

An example is gwbush.com, the spook website that digital agitprop outlet RTMark set up with the collaboration of computer programmer Zack Exley in 1999. The website was a mirror image of georgewbush.com – George W. Bush’s original website – but with the text replaced by a well-shaken blend of parody and political accusations. The at-the-time presidential candidate went ballistic at the tomfoolery and his lawyers issued a cease-or-desist letter. Afterwards, Exley – more traditional in his comedy taste – expressed concerns over the dubious interface of the website that might have misled honest websurfers since it wasn’t clearly labelled as a comic reappropriation. The point raised by Exley is crucial. Joey Skaggs, the RTMark group and all other merry media pranksters craved for that kind of misunderstanding because it represented their central argument. They were saying that satire is not objective journalism’s loyal sidekick. Satire at its best cannibalizes journalism exposing what is always an attempt at information control. As Joey Skaggs put it, media pranksters used ‘the media’ as a medium to make a statement about media. This echoes another logic straight from the Thirty-six Stratagems book: ‘Kill with a borrowed sword.’ Tactical Media always borrowed their weapons from their targets. ‘The place of a tactic belongs to the other’, wrote De Certau.

Enlarge

Tactical Media has never represented a formal movement but more an opportunity to be ‘seized upon’ after which it would be time ‘to move on’. However, the Tactical Media playbook hugely influenced a whole generation of political artists well beyond the 90s. The most famous example is probably the duo of media hoaxers The Yes Men. From the 1999 fake WTO website to the 2008 fake New York Times, Andy Bichlbaum and Mike Bonanno have always been performing the news, contesting the very idea of objective journalism. In the well-known 2004 BBC Bhopal media stunt, Andy Bichlbaum disguised himself as Dow Chemical’s spokesperson Jude Finisterra. Live on BBC, he declared that the company took ‘full responsibility’ for the infamous 1984 gas tragedy that caused the death of thousands of Indian people. Following a counterintuitive media logic, The Yes Men imagined a world where Dow took responsibility for its actions. In other words, they made a utopian world believable and almost possible, also thanks to the undisputed prestige of the BBC brand that mediated the utopia.

This strand of media activism represents a valuable lesson for aspiring rebels in a fictiocratic regime since it assimilates the operations of media manipulation. At the same time, it demonstrates that we don’t live in a world ‘without alternatives’ like some elites want us to believe, following a strand of thought that goes from Mark Fisher’s Capital Realism to Adam Curtis’ Hypernormalisation. Better realities are out there to be first imagined and then actually created. Representations are malleable and can be repurposed. This is also part of De Certau’s lesson. In this sense, ‘Trump has not been president’ hints at the possibility of imagining a time where Trump never got his tiny hands on the White House’s keys.

Am I claiming that counterfactualism might be an antidote to post-factualism? Yes and no. I have no intention to uphold counterfactual speculations as a legitimate tool for historical inquiry. The debate on the matter is fierce and I don’t want to step into it. However, I do have instinctive sympathy for Robert J. Evans’ arguments: counterfactual historians barter the straitjacket of historical determinism for an even tighter piece of clothing. To assert that the First World War would have never happened if Gavrilo Princip’s bullet missed the Archduke’s jugular vein implies a pretty narrow determinism. Nevertheless, counterfactualism can still be a useful tool – not for history but for media interventions. The alteration of the past grants the possibility to envision a different future, giving back a much-needed sense of agency.

A whole new essay is probably required to elaborate a satisfactory notion of agency. To make it short, I don’t mean here a sort of historical agency. I’m simply hinting to the basic agency of individual political participation as brought about in the Tactical Media manifesto. And as Robert J. Evans highlighted – counterfactualism is a specimen of right-wing historical speculations, too. Reappropriation works both ways, for good and for worse.

Conclusion

In a culture which offers video games, endless entertainment, drugs, alcohol, porn, sports, and a thousand other distractions to convince us of another reality, we want to cut all of that away. […] We are the ‘Dreamers of the Day,’ those who do not want our visions or even our fantasies to be escapes from reality. We want them to be the reality.

Richard Spencer, president of the National Policy Institute

In November 2016 – in the aftermath of Trump’s election – white-suprematist Richard Spencer harangued the crowd present at an alt-right conference in Washington DC. ‘Hail Trump!’, he shouted to an audience of raised arms. Poorly managed testosterone was clearly oozing into the air. In the half-hour long speech, Spencer styled alt-right activists as the ‘dreamers of the day’ that don’t accept mainstream reality because they want to live ‘in the world they imagine’.

There are some evident similarities between this approach and the progressive quest for a different world that I just described. Many have noted it. Right-wing activists are reappropriating style and tactics from the left. They are reappropriating reappropriation. It is not just the boundary between fiction and reality that has become a porous zone. Boundaries are blurring everywhere. Alex Jones and Adam Curtis say the same thing: there’s a fake reality that’s being pulled before our eyes. Of course, the same analysis leads to two very different visions of the world. However, the argument retains its relevance: clear-cut boundaries are a thing of the past. The game of reappropriation plays at an unprecedented speed.

The scope of this endless play lies outside the scope of this essay. But now that our travels in Fantasyland are almost over – the hard boundary of reality already in sight – it’s possible to draw a couple of conclusions about what we’ve learned. The first thing is that post-factuality as fictionality is not an ideological approach to reality. ‘Fictiocracy’ isn’t a pejorative term. It’s just my personal take on the matter. In this sense, the precariousness of reappropriation (today left, tomorrow right) doesn’t affect the argument.

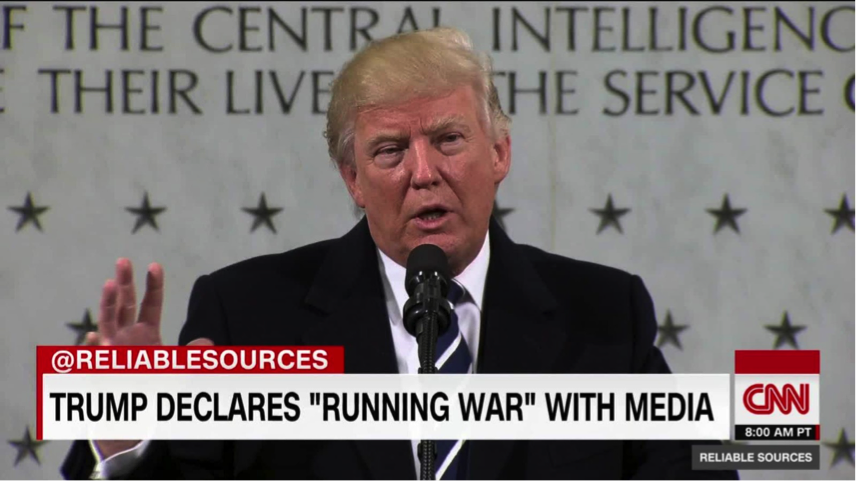

The second thing is a disturbing hallmark of fictiocracy (and I had to deal with Alex Jones’ gems like this one so the bar was pretty high). Languages of media and war are in such close proximity. The Gulf War as a media event, the Infowars and its store, the guerrilla tactics of alternative media and, last but not least, Trump’s war on media.

Enlarge

Media seem the continuation of war by other means. In a way, this is no news. The relationship between media and war has a solid research pedigree. However, it appears that fictiocracy is a particularly belligerent system of government prone to warlike fantasies. In 1970 Marshall McLuhan preconized: ‘World War III is a guerrilla information war with no division between military and civilian participation.’ Almost 40 years later, Senate Intelligence Committee chairman Richard Burr begged Facebook, Google and Twitter: ‘Don’t let nation-states disrupt our future. You’re the front line of defense for it.’ The ‘nation-states’ Burr refers to is foremost Russia, who you could say engaged in different forms of online information warfare in the lead-up to the 2016 presidential elections. The boundary between the military and civilians blurs like the one between reality and fiction. Fictiocracy as such finally expands its boundaries beyond traditional political geography.

Davide Banis is an editor and independent media researcher. He graduated with a Research MA in Media Studies from the University of Amsterdam. His work focuses on journalistic-political assemblage as they span across media. When he grows up, he wants to be a superhero.