Super Bowl commercials teach us how to conceive of surveillance. While Apple promises to fight Big Brother with a personal computer, Coca-Cola invites us to think different, i.e. positively about security cameras. The whitewashing of surveillance accompanies the ‘big brotherization’ of Apple. However, the whitewashing may only be a distraction from another more subtle, more effective (and after all more amusing) progression towards a dystopian future: the constant sharing without friction and language and thus without the distance that would allow for reflection and critical thinking. In this essay, I discuss the symbolic value of the year 1984 and its link to the ongoing move from lingual to visual communication. It underlines that the television screen or smartphone is the sibling of the surveillance camera and shows why the dystopian future we fear won’t be like George Orwell’s 1984 or Anthony Burgess’ 1985.

Whitewashing Surveillance

In the 2012 Super Bowl commercial ‘Security Cameras,’ Coca-Cola flipped the negative image of surveillance cameras by turning them into witnesses of goodwill. In the commercial, surveillance captures not crime but humanity witnessing surprising and moving scenes: ‘music addicts’ (the caption for a man who dances uninhibitedly in front of street musicians), ‘people stealing kisses’ (a couple on a bench, the boy spontaneously kissing the girl), ‘friendly gangs’ (four Arab men helping jumpstart a car), ‘rebels with a cause’ (someone holds up a poster that reads ‘nO TO RAcISm’), etc. With their ironic allusions to typical subjects of surveillance (‘addicts,’ ‘stealing,’ ‘gangs,’ ‘rebels’), the little microcosms of these scenes achieve what the commercial as a whole aims to do: the reinterpretation of fear-laden terms and symbols as sympathetic. This reinterpretation is reinforced by Supertramp’s superhit ‘give a Little Bit,’ with a pointed readjustment of its central line: ‘now’s the time that we need to share / So find yourself‘ becomes ‘now’s the time that we need to share / So send a smile.’ In place of self-discovery we are supposed to smile for the surveillance camera. This somewhat offbeat, sugarcoated perspective on surveillance perfectly exemplifies Coca-Cola’s mission ‘to inspire moments of optimism’ and thus assumes a mask of cool contemporaneity. In the given context, this pseudo-subversive cool turns into cynicism which happens to be exactly the rhetorical context needed by big-data business and just the other side of the ideological and commercial exploitation of concepts with politically positive connotations like ‘social,’ ‘share,’ ‘transparency,’ and ‘participation.’

The inspiration, and the payback, for this commercial is of course the Super Bowl commercial by Pepsi-Cola from 1996 in which a surveillance camera shows how a Coca-Cola distributor in a supermarket steals a Pepsi can from the fridge. Here it is not the function of the surveillance camera that is given new meaning; it is the judgment of the convicted culprit, who in the logic of advertisement actually does ‘the right thing.’ The twinkle in the eye is even implemented on the audio level. However, against the voluble enthusiasms of Coca-Cola, which are free of irony, it is to be feared that Pepsi’s gesture hardly has a chance.

To be sure, the positive take on the transparency and public display of human behavior is older than the WWW. In his 1985 monograph No Sense of Place: The Impact of Electronic Media on Social Behavior, Joshua Meyrowitz notes that the loss of privacy through electronic media reveals the ‘ordinariness’ of everyone,’ including the moral misbehavior of ‘extraordinary people’ i.e. their tax fraud and adultery: electronic media give a distinct advantage to the average person. Average people now have access to social information that once was not available to them. Further, they have information concerning the performers of high status roles. As a result, the distance, mystery, and mystification surrounding high status roles are minimized.’’ Radio and TV undermine the hierarchical model of the few powerful who observe and rule the many powerless. ‘The thing to fear,’ Meyrowitz holds, ‘is not the loss of privacy per se, but the nonreciprocal loss of privacy – that is, where we lose the ability to monitor those who monitor us.’

Such promotion of the loss of privacy was reinforced about 20 years later when Eric Schmidt and Jared Cohen, in their 2014 book The New Digital Age: Transforming Nations, Businesses, and Our Lives made the point that technology is a tool that can be used in different ways, meaning that surveillance technology can help the powerless against the powerful if for example shopkeepers in Addis Ababa or San Salvador publicize and document state corruption and irregularities. As Schmidt and Cohen conclude: ‘In fact, technology will empower people to police the police in a plethora of creative ways never before possible.’

Enlarge

Whatever we may think about Google shareholders praising transparency technology as empowerment of the masses, it is difficult to reject the notion that the oppressed indeed are able to fight back by documenting misuse of power. This is exactly the concept behind the human rights organization Videre est Credere that equips oppressed communities in Africa and elsewhere with cameras invisibly woven into the fabric of their clothes in order to expose violence and abuses. Policing the police is also one of the rationales for equipping the Metropolitan Police in Great Britain with 22,000 body-worn cameras: ‘Oppressive behaviour by police,’ we hear, ‘would decline’.

A special example of such ‘sousveillance’ is the killing of Philando Castile by a police officer in Minnesota recorded and uploaded to Facebook Live by his girlfriend on July 8, 2016. The footage is as disturbing as the fact of its recording. Mark Zuckerberg, in a Facebook post, expresses his hope that we never see such material again but leaves no doubt that Facebook does the right thing when it ensures that such material remains seeable: ‘The images we've seen this week are graphic and heartbreaking, and they shine a light on the fear that millions of members of our community live with every day. While I hope we never have to see another video like Diamond's, it reminds us why coming together to build a more open and connected world is so important -- and how far we still have to go.’

Whatever we think about these individual recordings and Zuckerberg’s claim to fight injustice by creating an open and connected world, the issue is at least as complicated as the right of US citizens to carry weapons for self-defense. The personal surveillance camera is the gun turned against the ‘bad boys;’ an argument in favor of the Second Amendment for the 21stcentury: the right to arm oneself with a camera in the name of justice and truth.

Big Brothers

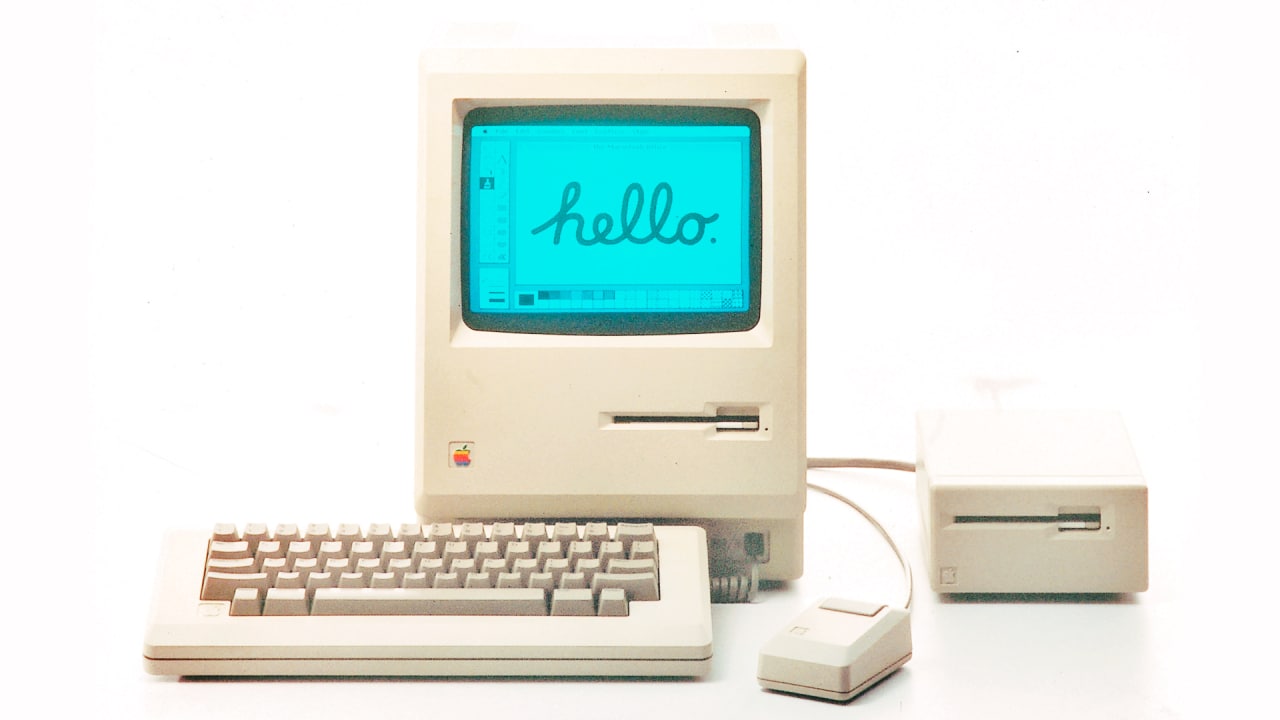

The last chapter of Meyrowitz’ book, in which he warns us for the nonreciprocal loss of privacy, is entitled ‘’Whither‚ 1984?’’ 1984 is presented in quotation marks to indicate a reference to Orwell’s novel. It was somewhat inevitable that in 1985 a book on the loss of privacy should refer to the novel 1984. For the same reason, it was not much of a surprise that Orwell’s novel occurred in another Super Bowl commercial significantly more famous than that one by Coca Cola. It was a commercial by a company that rather than selling sugar water, set off to change the world and headhunted with exactly this ambitious difference the CEO of Pepsi-Cola: Apple’s commercial to introduce Macintosh Computer produced for the Super Bowl on January 22, 1984.

‘On January 24th, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh, and you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like 1984.’ This announcement, as text and voice-over, appeared following a race between a group of armed men and a woman carrying a sledgehammer. As the sledgehammer demolishes a screen from which a man is haranguing a crowd of faceless figures, a murmur of wonder runs through the crowd and light floods the scene. Again, referring to Orwell’s novel 1984 seemed natural in 1984, even if there were no signs of any Big Brother taking over society. For Apple, however, the face of the enemy was not a dictator at all. It was an economic competitor: IBM, familiarly known as Big Blue. The advertising clip was using a cannon to shoot at a fly. Because, from a political perspective, even a big corporation like IBM is nothing compared to an authoritarian system – at least until Apple itself became a corporation and created its own ‘iCulture,’ with which it essentially set the terms of social communication, from the ‘lock-in effect’ to the censorship it imposed at its app-store.

But even if, in 1984, there was no Thought Police for Apple to swing a sledgehammer at, the company’s liberation rhetoric had a rational core: If computing power is real power, then the affordable personal computer equals the empowerment of the individual. How effective, we ask, more than three decades after 1984, is the computer in everyone’s hand against the things that are symbolized in the novel 1984?

That something has gone awry is already illustrated by the Big Brother Awards, which Apple has received twice since 1984: in 2011, for ‘dubious data protection guidelines,’ and again in 2013, for ‘comprehensive video surveillance’ of employees at Apple stores in Germany. Okay, unwanted awards like these can happen to anyone. Even the art fair Ars Electronica received the Austrian Big Brother Award in 2001, for ‘belittling biometrics’. And the files on the other internet giants have grown just as fat. Google, for example, received the Big Brother Award in 2012 and 2013 for ‘global data hunger’. And it certainly deserves two more Big Brother Awards: for building a smart city – which is actually nothing but 'Surveillance by Design’ – in Toronto’s Waterfront neighborhood, and for putting money over manners if Google really, as rumors in the summer of 2018 had it, returns to the Chinese market complying with the demands of the Communist Party and showing the world in their Orwellian image.

More exciting than attacks by ‘anti-technology’ groups is when the major corporations accuse each other of becoming Big Brother. This occurred implicitly on February 6, 2011, in another Super Bowl ad, in which Motorola compared its Android XOOM tablet to Apple’s iPad. The promise was huge this time, too: ‘The tablet to create a better world.’ This tagline follows a short film, which once again shows a big crowd of people with expressionless faces marching in formation, this time dressed not in gray but in shining white, and each plugged into an iPod. Only one figure, reading the novel 1984 on his tablet, is wearing dark clothes and later, at the office, produces an animated bouquet of flowers for one of the white-robed figures, whose wonder-filled gaze at the new device recalls an earlier ad for the Macintosh.

The promise of creating ‘a better world’ with this tablet can only be understood in reference to Apple’s promise that it could prevent Orwell’s 1984 with the Macintosh. Why a ‘better’ world? And why power to the people, as the title of the little film, ‘Empower the People,’ suggests? That there can be no other answer to this than a sentimental love story between a figure in dark clothing and a figure in white, is the actual point. Motorola unmasks the pathos, which in the Apple ad was still serious, by exaggerating it and basically saying with a wink of an eye: Apple once claimed it wanted to save the world, but it only wants to sell its products; we don’t want anything else either, but at least we admit it.

What Motorola attempted without much success in 2011, when it challenged Apple’s monopoly of the tablet market, Google tried to do for its Android system in the smartphone market. Finding itself on a collision course with Apple, Google explained the offensive at its Developers’ Conference in 2010 by citing the need to avoid a draconian future in which the only choice would be one man, one company, one device – and showed an image in which the date 1984 appeared under the tag line ‘Not the Future we Want' (Minute 19:55). Naturally, Google’s open-source operating system seemed to be the better alternative in comparison to Apple’s closed system. But Google is no less intent than Apple on achieving the monopolist’s ‘lock-in effect’ – and recent reports that Google is collecting our data even when we have opted out or don’t use our phone suggests that Google should do as it preaches.

Enlarge

Moreover, when it comes to surveillance there, are not many good things to be said about a business which boasts that nothing on the Internet can be hidden from it. A promise of this type is, of course, essential to the very nature of the product that turned Google into a verb. For we expect of a search engine that it will find whatever it is asked to find. But somehow it does sound threatening when Ex-CEO Eric Schmidt proudly announces, in 2010: ‘We know where you are. We know where you’ve been. We can more or less know what you’re thinking about.’ It sounds threatening, too, because this knowledge is not confined to Googling. Google’s email is also read by Google’s algorithms, and now there are Google’s Cloud Services, with which data that previously sat on personal computers wanders off to central servers (a beautiful gift for secret services, hackers and any future Big Brother regime). And there is (if it comes to this) Google Glass, which allows even one’s own gaze to be observed.

To round out the story: Facebook, which makes sure that our entire lives are exposed to observation, received the German Big Brother Award in 2011, for ‘targeted research of people and their personal relationships,’ and the Austrian Big Brother Award in both 2014, for ‘psycho-experiments with its members,’ and 2015, ‘for the patent that is intended to enable credit-scoring of the user’s friends.’ Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg doesn’t understand all the excitement about data protection and informational self-determination: After all, if a person has nothing to hide, he also has nothing to fear. For this level of Big Brother logic, at the Austrian Big Brother Awards of 2011 he deservedly received the ‘Special prize for ‘lifelong annoyance’ – an annoyance that since achieved wider acknowledgement.

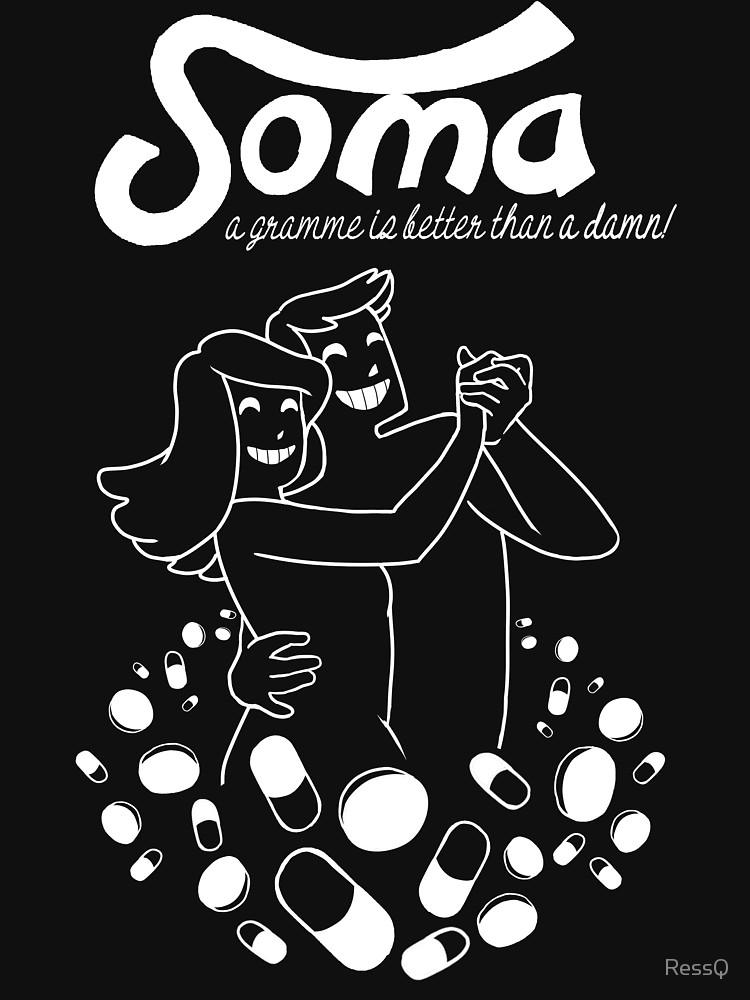

1984 did not happen and will never happen, nor will 1985, at least in the form in which Anthony Burgess described it in his 1978 novel of that name: as a totalitarian regime of labor unions that terrorize the land, Great Britain, with strikes and drive strike-breakers to their doom. After the neoliberal turn and the Cold War, we need to go back some years before Orwell to find a model for the future in Huxley’s novel Brave New World. Written in 1932, under the impact of the Roaring Twenties and Pavlovian behavioral conditioning, this was a more refined dystopia: a dystopia without complaining, one that its ‘victims,’ in their hedonism, didn’t even recognize as such. In 1985, Neil Postman’s essay ‘Amusing Ourselves to Death,’ inspired by the influence of television culture, proclaimed Huxley’s vision to be the more likely model for the future.

The ‘telly’ also plays a central role in Burgess’s novel 1985, in which the half-witted teenage daughter of the rebellious hero has only three things in her head: eating, watching television and masturbating. Burgess is still somewhat in Orwell’s debt when he portrays ideological indoctrination with a hodgepodge of history and the use of degraded language, now dubbed ‘Workers’ English.’ Postman’s essay, on the other hand, shows why the future will not look like either 1985 or 1984, but like Huxley’s satanic promise of permanent contentment. In Huxley, the drug Soma destroys the need for critical thinking, while in Postman it is television that performs this function. ‘Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business,’ as the subtitle of Postman’s essay reads, is not manipulated by a ‘consciousness industry’ that implants specific thoughts in the subject, the way Burgess portrayed it in his novel A Clockwork Orange, for example. Television is a zero sum medium that wants nothing more than for people to be amused. The formula is domestication through dumbing down.

As Adorno, central figure of Critical Theory and its concept of culture industry, once wrote in the mass-culture chapter of the Dialectic of Enlightenment: ‘The liberation that amusement promises is freedom from thinking as negation.’ The objective is to keep viewers continuously occupied so they don’t come up with ‘wrong ideas.’ This negation of negation becomes radical when it is liberated from the television in the living room by mobile and social media for which the cornerstone was laid in the year 1984, when Apple’s Macintosh and Facebook’s Zuckerberg first saw the light of day.

Mobile FOMO Soma

‘Never trust a computer you can’t lift.’ This is how Steve Jobs advertised the Macintosh. Since then, the devices have grown ever smaller. Today, we hold them casually in one hand while our thumb roams through all the amusement in the world. The new Soma is FOMO: fear of missing out. It ensures that amidst all the communication we are engaged in we can hardly find time to think anymore. Television is always with us thanks, first of all, to the iPhone; and Zuckerberg’s Facebook makes sure it always has something exciting on offer.

Big Brothers love little devices, above all when they are ubiquitous. When even the dust is full of software and all things communicate with each other, there will be no more aspects of life that are not turned into data, that is: analyzable and controllable. The control will present itself as love and support, the same way Microsoft, in the summer of 2015, tried to present its new operating system Windows 10, which wants to know every single thing you do on the computer and the Internet – the better, we are told, to protect its users from cybercrime. A bold move, so soon after Snowden, but one that could end up winning, for since 9/11 the business of security in exchange for transparency is doing very well.

This brave new world will not be able to do without surveillance, but the latter will occur in our interest and we ourselves will install it each time. For in fact, as long as we are nicely amusing ourselves with Facebook, WhatsApp, Snapchat, Instagram or whatever, there is nothing to fear. The much-lamented dumbing down through those media is no unwanted side effect. It is also important in Huxley, where oxygen is withheld from the embryos of the ‘Epsilons’ (the caste used for lower-level tasks) in order to keep them intellectually limited. Naturally, in the 21st century, this does not take such a drastic form. Instead of oxygen denial there is now the information surplus, its permanence ensured by mobile and social media. The more incisive anti-film to Apple’s ‘1984’ would give the men iPhones as weapons, which they would try to force upon the woman they race against. The woman would have the features of Steve Jobs, who, as we know, kept his own children away from iPhones. The worst are those who publicly preach wine and drink water in private.

The subject at hand must be discussed beyond the issue of cameras and data mining. We also need to take into account the politics of communication. For this reason, we need to come back to Facebook.

In early 2016, the Internet was losing its mind over a picture of Mark Zuckerberg walking through a sea of people in VR headsets at the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona. The commentators of the web community didn’t fail to soon connect this image to Orwell’s 1984. But why did they do so? Aren’t people watching a screen different from people being watched?

Orwell’s novel has two metaphors for these two different relationships to the screen: ‘Thought Crime’ and the ‘Ministry of Truth’. While thought crimes need to be detected, the alleged ‘truth’ needs to be injected. In combination with observation, indoctrination is in place. In other words, and applying the titles of two books by Michel Foucault: surveillance and punishment go hand in hand with the order of discourse. For this reason, Orwell’s dystopia is not only filled with cameras, but also with television screens.

We may not be surprised that in 1948, under the impression of Hitler and Göbbels, Orwell reduces the role of mass media within an autocratic regime to a tool of political indoctrination. However, prior to this, Huxley had already based his dystopia on entertainment rather than direct suppression. This is the more moderate, though not necessarily more modern form of control. ‘Bread and circuses’ was the recipe for (keeping) power as early as the ancient Rome. And it is still so today. Soap opera beats Big Brother; entertainment accompanies and to a degree substitutes control – as Adorno once famously put it in the Dialectic of Enlightenment chapter on Culture Industry: 'The liberation which amusement promises is from thinking as negation.' While the intended result of surveillance is self-censorship, self-censorship, on the other hand, is superseded by bread and circuses. In Huxley’s Brave New World,the bread comes as a drug. Today it comes as constant distraction and the suppression of critical thinking. Thinking can only be critical if it is contemplative and profound. It can’t thrive on the ground of distraction, short attention-span and phatic communication.

It was Rousseau who in his book Emile or On Education stated: ‘There is no subjugation so perfect as that which keeps the appearance of freedom, for in that way one captures violation itself.’ This update to Machiavelli’s The Prince is the motto of chapter 12 (‘Managing Information and Minds’) in Bertram Gross’ book Friendly Fascism of 1980, where a specific form of fascism is depicted that promises citizens cheap and plentiful material goods while taking away their civil and political rights. This once much discussed book has recently gained new attention in the context of the Trump presidency.

While it remains to be seen whether Trump will bring about such fascism (or whether China will beat the US to it), we should not delay the exploration of the role digital media and social networks play in this regard. What exactly is the link between Zuckerberg and Orwell’s 1984 or the ‘brave new world’ of a ‘friendly fascism’ for that matter? What we ought to discuss is the shift away from a conscious, mindful self-understanding that digital technology brings about. The affirmation of the political status quo – this is the rationale of the bread and circuses-strategy – starts with the avoidance of thinking, insofar as thinking, real thinking, is always, as Adorno notes, also negation. The very fundament of thinking, language, is under siege today by mobile and social media.

Selfie-Society Without Self-Consciousness

Sex, vacation or a job interview – everything we experience can be internally recorded and later viewed again, either alone or with friends, on an external screen. This, at least, is how it was in the episode ‘The Entire History of You,’ which aired in December 2011 as part of the British science fiction film series ‘Black Mirror.’ It was music to the ears of Mark Zuckerberg, who laid out $2 billion to purchase the virtual reality technology Oculus Rift and describes, in the summer of 2015, Facebook’s plans for immersive 360-degree videos as follows: ‘We'll have AR and other devices that we can wear almost all the time to improve our experience and communication. One day, I believe we'll be able to send full, rich thoughts to each other directly using technology. You'll just be able to think of something and your friends will immediately be able to experience it too if you'd like.’ Zuckerberg considers this prospect of automatic sharing – and ‘end of language’ as The Atlantic calls it – ‘the ultimate communication technology’ and has 60 engineers working on building a brain-computer interface in Building 8. It is a future that is already well underway.

That it was possible to document experiences without describing them had already been proclaimed by Zuckerberg at Facebook’s Developers Conference in 2011, under the slogan ‘frictionless sharing.’ Concretely, what this means, for example, is that the song that you are listening to on Spotify and the film you are watching on Netflix are automatically displayed to your Facebook friends if you have activated the corresponding function. You no longer need to give a reason for this piece of news, or even articulate it. Now the activities communicate themselves. The new slogan is: ‘It posts, therefore I am.’ Because the process lacks a conscious element, it no longer has much to do with Descartes’ formula for self-knowledge.

Actually, the muting begins even earlier, while we are still pressing the button ourselves to transmit the photos, spontaneously and unreflectively, that let the network know what we are doing without us having to articulate it. A picture isn’t just ‘worth a thousand words’ – it eliminates the necessity for words altogether. Things communicate themselves when they are photographed or registered automatically. This is why, in 1927, Siegfried Kracauer called photography ‘a strike against understanding’: the mechanical reproduction of reality makes its conscious grasp unnecessary.

Ninety years later, the stakes have risen. Not only things, but human beings are recording and reproducing themselves, and doing it in ways that bypass the threshold of consciousness. On Facebook and other social networks we ‘describe’ our lives by living them, and in the process we produce autobiographies that have never passed through our brains. Simultaneously, the algorithms are very precisely registering what is happening, as it happens – and consequently know more about us than we do ourselves.

It is this knowledge gap that is the source of the problem. As we give more and more data to the algorithms, we ourselves process less and less of it. The more our speaking, naming and describing are supplanted by automatic registration and audiovisual copying, the less we ourselves are forced to reflect on and come to terms with the world and our role in it. Language is the medium with which we establish distance from the world, in order to see and understand it more clearly. Every attempt to transcend language also risks the loss of cognition.

For this reason, the BBC slogan ‘We don’t just report a story, we live it’ is quite problematic. Above all, it is problematic that Zuckerberg imagines the future of journalism in precisely this way: ‘more immersive content like VR,’ more ‘rich content’ instead of ‘just text and photos.’ As Zuckerberg told BuzzFeed News in the spring of 2016: ‘We’re entering this new golden age of video … I wouldn’t be surprised if you fast-forward five years and most of the content that people see on Facebook and are sharing on a day-to-day basis is video.’ But what happens, in days to come, if people who witness something on Facebook’s video livestream, or via Oculus Rift, won’t accept the laborious research of experts who still hold up the idea of quality journalism? What if, when something occurs, we are no longer compelled to put it into words, but can simply play it on the screen for others? What if our encounter with the world is reduced to recording it?

Kracauer characterized photography as the self-annunciation of material things: ‘For in the artwork the meaning of the object takes on spatial appearance, whereas in photography the spatial appearance of an object is its meaning.’ Seventy years later, French philosopher Jean Baudrillard dramatizes the process as the ‘contest between the will of the subject to impose order, a point of view, and the will of the object to impose itself in its discontinuity and momentariness.’ The winners in this contest are the objects, which give a factual report on ‘the state of the world in our absence.’ That this, admittedly, is a win for both sides is suggested by Baudrillard’s explanation of the pleasure we feel in taking photographs: ‘Overall, when it comes to making sense, the world is quite disappointing. Seen in detail and caught by surprise, it is always fully and perfectly evident.’ We let the objects speak so the void left by our falling mute is filled; the more detail, the better.

In Mark Zuckerberg’s communication utopia, the aim is to apply this model to humanity itself: the subject should engage in self-display, bypassing consciousness. When Zuckerberg talks about the video trend he has identified, he stresses that he is not talking about films whose content or form have been intentionally shaped; he is talking about the coveted ‘raw material’ of social life. In this utopia the subject engages in self-display, bypassing consciousness. The paradoxical result is an automatic autobiography that we ‘write’ by living – a post-human, algorithmic autobiography. As I note in my study Facebook Society: ‘The automatization of the report and the expulsion of the subject from self-narration are the logical consequences of the transparency doctrine: Human beings, consciously and unconsciously, always want to conceal something; only machines have an objective interest in knowledge.’

A scary, uncanny symbol of the victory of objects over the subject is an all-round object itself: Amazon’s Alexa. This object symbolizes monitoring without a screen. Its sinister and alarming sentence would be ‘Big brother is listening’ if such listening would still alarm people. But the success of Alexa and similar objects lies in the fact that they seem to be exactly what we want: we want these objects to be listening – as servants that take our orders.

This is the update to Rousseau’s paradoxical notion about repression quoted in Gross’ Friendly Fascism: There is no subjugation so perfect as that which keeps the appearance of authority to give directives. For this reason, we also will buy microwaves, toasters and all kinds of appliances that we can boss around. We will do so for the efficiency and because we consider all those small but real comforts provided as a decent pay-off for the serious but vague risks of being surveilled.

Moreover, what does the physical condition of data matter once the Internet of things makes sure that all those data areaccumulated and analyzed? Alexa is only the more visible, more interactive interface for a constellation in which no action occurs without leaving a trace. When your coffee-machine and your refrigerator talk to your insurance company it is of little interest whether they gathered their data by listening to you or by otherwise observing you.

Enlarge

I started this essay by elaborating Coca-Cola’s whitewashing of surveillance cameras and argued that distraction – as the suppression of critical thinking – accompanies and substitutes control: you don’t need to subject people to the camera if you succeed in hooking them to the ‘telly’ (or its 21st century versions: social and mobile media). I then considered the visualization of communication as a loss of contemplation and consciousness and stated the predominance of the order of objects over the point of view of humans. We finally noted that this dominance will be reinforced by smart objects that observe our everyday actions in order to better understand them and us. The profile of human behavior that such ubiquitous data mining allows is the counterpart to the vanishing self-awareness within the selfie-society of automatic autobiographies.

Coming back to the promise in Apple’s famous Super Ball ad, it is clear that 1984 and all the years since have indeed not been like Orwell’s 1984. But that doesn’t mean that what lies ahead is not to be feared. The all-clear that Nam June Paik and his avant-garde friends sounded in their art project Good Morning Mr. Orwell at New Year's Day 1984 – and that many other believers in the utopian power of electronic and especially digital media echoed – was not confirmed by the advances of digital media that followed Apple’s Macintosh.

We now know that neither connecting people by television nor by the internet shields society against totalitarianism. We are starting to understand that control is not only exercised by surveillance cameras but also by the cameras which we voluntarily place in our pockets and allow to collect our data. We suspect that resistance must start with the skepticism toward technologies and forms of interaction that undermine the distance needed to establish a reflective, critical relationship to the world and to ourselves. Otherwise, we will blindly, and ever amusingly, slip into a dystopian future which will be so difficult to detect and avoid precisely because it won’t look like 1984.

Roberto Simanowski currently works as media theorist in Basel. He has previously held professorships for German and Media Studies at Brown University, University of Basel, and City University of Hong Kong. His most recent publications include: Digital Humanities and Digital Media: Conversations on Politics, Culture, Aesthetics and Literacy (Open Humanities Press 2016), Data Love. The Seduction and Betrayal of Digital Technologies (University of Columbia Press 2016) and Facebook Society. Losing our Selves in Sharing Ourselves (Columbia University Press 2018) as well as Waste. A New Media Primer and The Death Algorithm and Other Digital Dilemma (both MIT Press 2018).

References

Adorno, Theodor W.; Horkheimer, Max, Dialectic of Enlightenment, trans. by J. Cumming. New York: Continuum, 1991 (Translation modified).

Baudrillard, Jean, Fotografien 1985-1998, catalogue, ed. by Peter Weibel, Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz 1999.

Kracauer, Siegfried, ‘Photography.’ Trans. Thomas Y. Levin. Critical Inquiry19, no. 3 (Spring 1993): 421–36.

Meyrowitz, Joshua, No Sense of Place. The Impact of Electronic Media on Social Behavior, Oxford 1985.

Schmidt, Eric; Cohen, Jared, The New Digital Age: Transforming Nations, Businesses, and Our Lives.New York: Vintage, 2014.

Simanowski, Roberto, Facebook Society. Losing Ourselves in Sharing Ourselves Facebook-Gesellschaft, New York: Columbia University Press 2018.