It is true that software cannot exercise its powers of lightness except through the weight of hardware. Italo Calvino, Six Memos for the Next Millenium

We live in a world of glowing rectangles. Our devices emit a bluish light, akin to that from the cerulean sky. Even when they sleep, computers softly pulse tiny LEDs on and off, making their presence known through light. And where they were once uniformly black and dark gray, devices are now white, shiny, and reflective: they add light not just by emitting it, but by reflecting it. The airbrushed aluminium of Macintosh computers has a luminous flux that ranks higher on light meters than pure, snowy white.

The glow emitted from these aesthetic machines requires an equally reflective and almost holy environment in return. It asks for purity and for a certain kind of touch. Did you baptize – I mean, wash – your hands before putting your fingers on your devices? More than once I’ve caught other people mindlessly wiping off the dust or bits of my breakfast from the keyboard well of my MacBook Pro in gestures of primal protection and unconscious respect. Devices – and Apple products especially – have a halo.

For Apple, this halo was present from the company’s very first self-portrait in 1976. The first, original Apple logo depicts Newton reading under a tree, with an apple hanging above his head, radiating white light – a reference to the popular legend that Newton discovered gravity three hundred years earlier when the fruit fell on his head. In the first Apple logo, this legendary fruit glows: it’s Newton’s bright idea, encompassed in a halo of light that led to his – and our – enlightenment.

Enlarge

Original Apple logo, designed by Ronald Wayne in 1976, depicting Newton sitting under an apple tree.

Newton’s glowing apple promises knowledge, and indeed, only a few months later, the Apple logo was changed to one where the apple was bitten, as if from the tree of knowledge in the biblical Garden of Eden. But this revised bite in the new Apple logo did not result in expulsion from utopia, as Adam’s bite did. Rather, it secured entry into an Edenic paradise of a Garden of Technology. This kind of bite was a ‘byte’ that ushered in a promise of the techno-utopia: an idyllic state in which technology insures collective survival and success ‘allowing us more efficient control of life and providing solutions to all problems’, as Richard Stivers has put it. This progress was not the drive forward into the dystopic visions of Orwell’s 1984 or Huxley’s Brave New World, but rather towards a new kind of semi-religious utopianism, where the device, rather than Christ, wears the halo.

Enlarge

Second Apple logo, designed by Robert Janoff in 1977, depicting an apple with a bite taken out of it.

Halos are symbols of divinity and religiosity. Even pop-culture icon Beyoncé Knowles adorns her otherwise secular image with a bejeweled cross on the official press for her 2008 love ballad, ‘Halo’. And the cross of Christ has the most followers of any organized religion, with over two billion people claiming it to varying degrees. But when will the devotion to the technological device usurp the cross’s place?

Enlarge

Beyoncé Knowles’ promotional shot for her 2008 hit R&B-song, ‘Halo’; a cross dangles from her bracelet.

Kyle May, editor in chief of CLOG magazine, speculates that with over ten billion songs sold on iTunes, over five billion apps in the App store and over 30 million iPods, Apple has ‘somewhere between one-seventh and five times as many followers as Christianity’. Indeed Apple’s famous ad campaign, ‘I’m a PC / I’m a Mac’ sets up a common strategy among religious faiths to praise followers and demonize others. As Volker Fischer pointed out in The i-Cosmos, Steve Jobs himself made godly references in his introduction of the iPhone in 2007: he compared touching the iPhone screen to God’s divine touch of man in Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel fresco The Creation of Adam. In the fresco, God’s divine touch imbues man with life; with the iPhone, man’s touch imbues man with divine control. And while God gave freely gave life to man, man had to steal knowledge for himself through the biblical apple. Jobs’ newly launched iPhone had both at once.

Enlarge

Apple’s popular ‘I’m a PC | I’m a Mac’ casts Mac users as younger, hipper, spryer and more in-the-now, and demonizes the non-believers.

Apple commercial stores themselves have been variously referred to as temples and cathedrals. Inside these sites of high-tech worship, Apple Geniuses wait to bestow sermons of knowledge upon you and solve your problems, but only if you confess the sins you committed against your devices (as in, ‘Did you drop this?’) first.

The Apple stores are the totemic loci of the Edenic lust for technology. Numbering over 500 in over twenty different countries, they are the sites of the new halo – the neo-nimbus, as I call it – where the glow of the device is most visible through the clear glass of transparent, promised attainability. Inside the stores – each one marked with an Apple logo that hangs as cross over the entrance – lie rows of products arranged spaciously on altars, pedestalized in utopian perfection. The environment is minimalistic, reflective, transparent, and pure. This is a site of minimal friction, where the pinnacle of consumerism – the cash register – has been replaced with the fluid decentrality and easeful swiftness of portable scanners. The scanners are souped-up iPhones, of course. The stores may be crowded, but in spirit they are empty. Their emptiness suggests the Eastern sense of presence of possibility rather than the Western conception of emptiness as nothingness, Paul Adamson noted in Eichler Idyll. It’s as if the the open, transparent design of Apple stores says to you: the world is your oyster, and your shell is glass.

The glass walls of the Apple store represent the ultimate openness. ‘Glass,’ notes structural engineer Rob Nijsse in an article for Clog, ‘is a transparent material representing our wish for an open, indeed, transparent society. What you see is what you get and we have no secrets.’ Architect Paul Scheerbart became famous in 1914 by proclaiming in his book Glass Architecture, that glass ‘has brought in a new era’. With glass, there are no visual whispers, and there is no expectation of privacy. Rather, there is a certain and definitive publicness: the Apple store is the new public square, where purchasers and internet surfers commingle in a seemingly unquestioned belonging.

This sense of publicity was what led media artist Kyle McDonald to first start taking pictures of unknowing bystanders at the Apple store in his work, People Staring at Computers. McDonald noted that the right to privacy in a public space is quite limited unless people have secluded themselves to places where they have high expectations of privacy, such as bathrooms or dressing rooms. Apple’s glass gives no room to such private expectations. Even society’s have-nots frequent the piazza of the Apple store: writer Rachel Aviv followed the stories of homeless queer and trans youth in New York, who visit the stores to research subsidized housing online and track each other via Facebook. One young man even wrote his college essay application in the Apple Store on 5th Avenue – a public square that is flattened only in comparison to the three-dimensional glass cube that iconifies it.

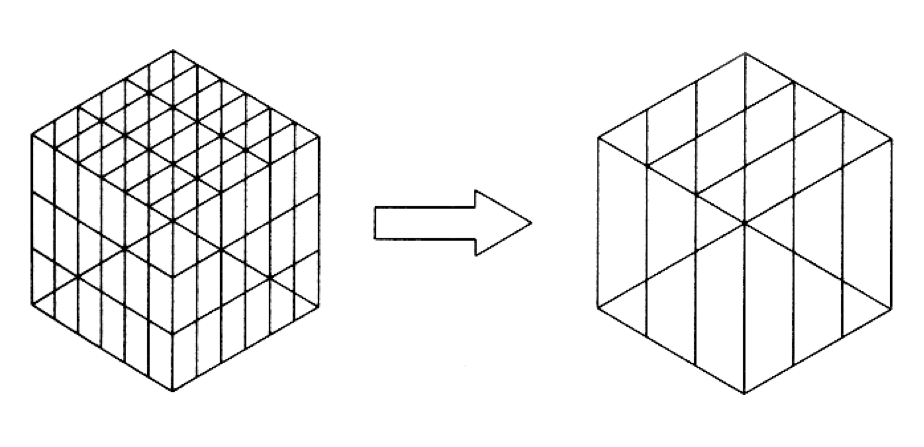

Indeed, the 5th Avenue Apple store signifies a commitment to reducing even what minimalism has made bare from its inception. In a $6.6 million renovation, Apple reduced the number of glass panels on its cube of an entrance from ninety to a mere fifteen. This revision replaced transparency with hyper-transparency. The Bird-safe Glass Foundation was surely unhappy. Descending into the subterranean store is not an Umberto Eco-tian Travel in Hyperreality but rather a travel into a kind of hyperethereality.

Enlarge

The 5th Avenue Apple Store in New York, NY.

Enlarge

The reduction of the iconic glass cube of the 5th Avenue Apple Store from 90 panels of glass to 15.

This hyperethereality is reminiscent of Yves Klein’s Air Architecture – his utopian vision that combined social theory with fantastical architecture in an optimistic philosophy. Instead of roofs, Klein designed streams of compressed air to keep rain from falling onto spaces, for instance. Klein’s designs free humans from materialism, allowing them to live in a levitation that he so clearly sought in his famous photograph, Jumping into the Void. Some of his drawings from this period, such as Fountains of Water and a Roof of Fire, are reminiscent of the glass, cubic designs of Apple Retail Stores.

Enlarge

Yves Klein, Fontaines d’eau et de toit de feu, 1959.

Within the idyllic landscapes of the Apple Store, the only imperfections are human beings themselves. And so, with their uniforms, Apple employees cede any attempt to match the heroism of the halo-ic objects they sell. Rather than dressing sharply – in suits, for instance – the staff wear T-shirts, emblematic of a youth-culture that is more perfectly poised to dish out the constant-newness of the digital device. Historian and theorist Kazys Varnelis thinks this choice is made for fear of shifting focus away from the machine. In Clog article ‘The Architect’ he writes:

The incongruity of the staff wearing out-of-style T-shirts while selling or repairing carefully designed objects in minimalist environments is no accident. At Prada, the stylish sales staff overshadows the object they are intended to sell… [At the Apple store,] humans are superfluous to machines in a new, more perfect order.

If the unnecessary human body is meant to sit in the penumbra of the pedestalized machine in any case, then it’s best that they not even try to step out of its shadow.

Digital devices themselves are ethereal and authorless, born not out of carnal sin but from what I call an immaculate digital birth. Or perhaps, if they do have an author, it’s Steve Jobs himself: this explains the outpouring of grief over his death, which Michael Kubo suggests was actually ‘a need to personify our empathy with objects by projecting that empathy onto a figure now heroized, reductively, as their sole creator’. The ‘S’ in Siri – the iPhone’s intelligent, voice activated personal assistant – may just be a stand in for Steve himself. Perhaps Steve Jobs died so that Siri could live.

In their just-unboxed condition, the devices appear untouched by human hands. This mythos is threatened only by intermittent exposés on poor conditions in Chinese factories like Foxconn, where Apple manufactures its products in a walled campus dubbed iPod City. Ironically, not far from the walls of this anti-Edenic factory, in nearby cities such as Kunming, BBC staff has discovered scores of fake Apple Stores. The fakes were near-perfect replicas of the real, filled with chrome walls and high wooden tables. Such faithful replication is difficult in the case of the Apple Store because, as Mika Savela remarked, ‘minimalism, by definition, has very little to copy’. Even the staff working in the stores believed them to be real. The halos of the devices – even the fake ones – are infectious, convincing, and ready for even more pedestals than authorized Apple Stores can provide.

If the Apple stores are Edenic, then the devices themselves offer little glimpses into utopia. This is the promise of their pure halos: ‘We will make them bright and pure and honest about being high tech,’ said Jobs at the 1983 International Design Conference, describing Apple’s forthcoming Macintosh computer. But utopia, by definition, is a blank slate. A utopia is a non-place, an un-topos. The device, on the other hand, commands the space around it. While its minimalism promises simplicity, it requires simplicity in return. Apple products look out of place in messes. ‘Place a Mac in the center of a room,’ notes writer Hanny Hindi in ‘Duck, Duck, Duck, iPad!’, ‘and it demands that the rest of the space conform to its aesthetic. Many of us comply.’ The lifestyle blog Unclutterer features a ‘Workspace of the Week’ – all of which are minor variants on clean and well-lit spaces, centered around shiny Macs. Indeed the cleanliness of the devices instills a sense of guilt in any user snacking on something wet or crumbly in its immediate presence.

It is no wonder we respect our devices: they promise a better tomorrow, even when we’re lying in bed watching trashy movies on their shiny screens. So we protect the devices’ vows with prophylactic sheaths and cases. iPhone cases are to us what plastic sofa covers were to our grandmothers. The protective case is the device’s Botox, keeping it ever-young, because once it leaves the Edenic Apple Store, its neo-nimbus begins to fade. We encase the device to prolong the glow of its halo.

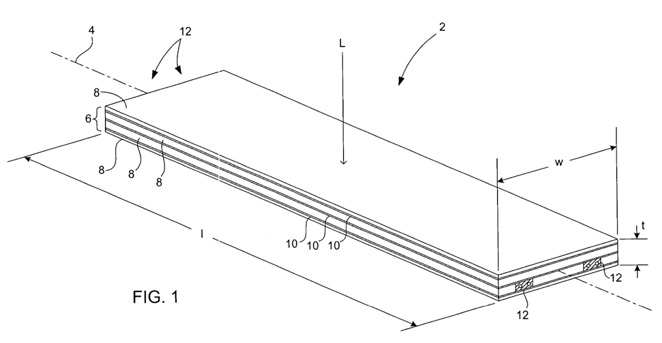

The halo of the device is strongest in the just-unboxed device. ‘Unboxing’ is a video category on YouTube that lives on an island between shopping channel talk-throughs and user-generated product reviews, offering the viewer the ‘vicarious experience of removing a newly purchased product (usually an electrical device of some sort) from its packaging’. Unboxing videos are visual documentation of the consumer-product relationship. They offer performative snapshots at the height of consumer anticipation, before products commence their decline into disuse, neglect, and inevitable disintegration.

Importantly, the device itself is rarely turned on in these videos. Unboxing is about packaging and its removal, a de-sheathing that foregrounds the first sensuous encounter with the Heideggerian presence-at-hand of the object, itself. The unboxing is the unconsummated striptease of the digital universe. As if to provide ultimate viewer fantasy, the most-skilled unboxers make themselves invisible from their positions behind the camera, showing only their hands as if in a first-person shooter game.

To writer Mark O’Connell, these ceremonious unboxings have religious overtones:

The unboxer acts as a kind of priest in the polytheistic faith of merchandise, a mediator between the congregation of consumer subjects and the numinous object itself. The task that he sets himself (and, as with priests generally, it’s almost always a he) is the task of revelation.

But in these videos, the device itself is often trash-talked (‘let’s unbox this sucker’ or ‘let’s open this bad boy’) and eroticized (‘this device is sexy as hell’). To watch these videos is to both momentarily quell and simultaneously itch a quasi-pornographic lust after the device.

Steve and I spend a lot of time on the packaging [...] I love the process of unpacking something. You design a ritual of unpacking to make the product feel special. Packaging can be theater, it can create a story. Jonathan Ives, Apple lead designer

The lust after the seductive electronic object of desire has two different pulls, and consumerism is surely one of them. But another and perhaps stranger pull is one that yanks on the egocentric heartstrings of narcissism. The ‘I’ in the family of iDevices refers to ‘internet’, ‘individual’, ‘information’, ‘inspire’, and other such i-words, noted Jobswhen he released the iMac computer. But the ‘i’ also refers to the ego quite literally: ‘I’ can also be seen as the first-person pronoun rather than as an abbreviation for something else. When I mention my iDevices by their proper names – iPhone, iPad, iMac – I get to talk about myself in disguise. ‘Let’s admit, wrote Michael Green in Zen & the Art of the Macintosh, ‘that beneath the ‘’seductive fascination’’ [of computers] we may well find a secret thread of digital narcissism running through this whole relationship, i.e. the intellect hopelessly entranced by the well-packaged feedback of its own wonderful inner workings.’ Green’s book is about his relationship to the computer, but his hidden subject, he admits, is himself.

Whether narcissistic or not, the lust is certainly ever-present, and continually unfulfilled. The objects of desire are objects of designed obsolescence. Old iPhones are typically discarded for new ones every two years, or even more frequently, and their obsolescence begins from the moment they’re unboxed. These devices are built to shine and then die. That is why their halos are so precious: the light fades so rapidly, so we must hold on to it while it’s bright. We are caught in the ‘digital undertow’ of economic cycles to borrow Green’s term – ‘betrayed’, as Adorno would put it, by the every-changing tides of the silicon gods.

Enlarge

Illustration from Zen & the Art of the Macintosh by Michael Green.

After all, glass breaks. Shattered iPhone screens are all too common. The symbolic transparency of the device is a façade that both fuels its obsolescence and disguises the impenetrability of its insides. You cannot open up your phone; you must plot, scheme, and commit the crime of iOS ‘jailbreaking’ to access its insides. Steve Jobs’ biographer, Walter Isaacson, notes that Jobs ‘had never liked the idea of people being able to open things’. This is a battle of the closed versus the open, the transparent versus the opaque. Even Apple’s headquarters are housed on ‘Infinite Loop’ in Cupertino – not on a street, avenue, boulevard, or lane, but on a closed loop. Axel Kilian has explained that the second Apple Campus – now called Apple Park – was planned not as a typical office structure, but of a building that resembles a giant ring, putting architecture in direct conversation with the archetype of a perfect circle.

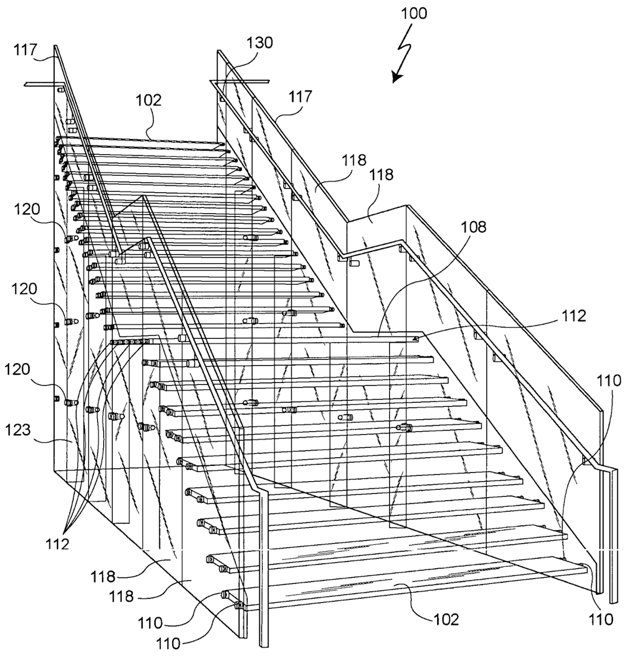

A circle, of course, is a closed geometric form. It has no clear entrance – which is to say, it lacks a certain permeability we often expect in architecture. In this way it is reminiscent of the Apple Store, which purports a kind of openness through glass, while the glass itself is walled off by the protective rights of U.S. intellectual property law. Apple holds the patents to the design of the iconic glass staircases of their commercial landscapes, and trademark approval for their store designs more generally.

Enlarge

US Patent 7165362, 'Glass Support Member,' which Apple Computer Inc. filed for the design of the glass stairs in their retail stores.

Enlarge

Detail of the stair from US Patent 7165362, 'Glass Support Member'.

So the vision of this techno-utopia is one of a separated perfectionism, a walled-off island of dreams for a better Tomorrowland. All its aesthetics are bathed in the flattering, bluish-white light of the halo of our devices. This is the halo that architect Norman Foster desired to build into the Apple 2 Campus.

This is why I love Apple Stores: they are the totemic loci of the promises technology extends, and of the retractions of those promises. I’ve visited stores across the east and west coasts of the United States. In Boston, I was told to stop taking pictures of the store with my digital SLR, so I started taking pictures from the demo models of the iPhones and iPads themselves. I looked at thousands of pictures that others had snapped on the iDevices. These photographs were mostly ‘selfies,’ or shots people took of themselves by pointing the ‘i’ of the device at their own eyes. But I found hundreds of beautifully abstract images of iPhone flashes reflected in chrome walls, or white, snaky cords descending into the shadows of birch tables. I made Genius appointments. I looked under the tables. I asked myself who the ideal consumer was and searched for answers in the store. The iTunes libraries told me what kind of music this archetype listened to while working out (it was all too slow), and what his children looked like (they like baseball).

In the public square of the Apple Store, I was surrounded by the numinosity of the device. I was not immune to its divine seduction, nor to its promise of a more-perfect technological utopia. But in a world where the technological realm lacks the Aristotelian dimensions of space, time, and place, I found them again in the Apple Stores. I felt the light of the halos of our devices, and also saw their shadows.

Enlarge

Apple Campus 2 plans, Cupertino, CA, designed by Norman Foster.

Also, a halo.

Liat Berdugo is an artist, writer, and curator whose work focuses on embodiment and digitality, archive theory, and new economies. Her work has been exhibited in galleries and festivals internationally, and she collaborates widely with individuals and archives. She is currently an assistant professor of Art + Architecture at the University of San Francisco. More at liatberdugo.com.

Literature

Paul Adamson, ‘Eichler Idyll,’ Clog (9 Feb. 2012), 17.

Theodor W. Adorno, The Culture Industry: Selected Essays on Mass Culture (London: Routledge, 2001).

Werner Buchholtz, Planning a Computer System (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1962).

Italo Calvino, Six Memos for the Next Millennium (New York: Vintage Books, 1993).

Umberto Eco, Travels in Hyperreality: Essays (San Diego: Harcourt, 1986).

Volker Fischer, The i-Cosmos: Might, Myth, and Magic of a Brand (Stuttgart and London: Edition Axel Menges, 2011).

Michael Green, Zen & the Art of the Macintosh: Discoveries on the Path to Computer Enlightenment (Philadelphia: Running Press, 1986).

Hanny Hindi, ‘Duck, Duck, Duck, iPad!’ Clog (9 Feb. 2012), 65.

Walter Isaacson, Steve Jobs (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011).

Axel Kilian, ‘Monumental Simplicity,’ Clog (9 Feb. 2012), 95.

Michael Kubo, ‘Object-Oriented,’ Clog (9 Feb. 2012), 109.

Kyle May, ‘The Second Coming?’ Clog (9 Feb. 2012) 83.

Rob Nijsse, ‘The China Syndrome and Apple’s Glass Architecture,’ Clog (9 Feb. 2012),57.

Mika Savela, ‘A Fruit of the Modern,’ Clog (9 Feb. 2012), 55.

Paul Scheerbart, Glass Architecture (New York: Praeger, 1972).

Richard Stivers, ‘Technology as Magic,’ lecture, Azusa Pacific University, Azusa, CA (10 Nov. 2004).

Kazys Varnelis, ‘The Architect,’ Clog (9 Feb. 2012), 45.