Bodies - photoshopped, facetuned, beautified, deepfaked, synthesized simulated, rendered, digitized. What do these impalpable figures on the surface of the screen want from our palpable fingers holding it? Do they want something? Puzzled by the idea that images might want something (as suggested by WJT Mitchell, 2005) I started exploring possible modes of relating to digital images through a performative frame. This became ‘Digital Golem, Gesticulating Hybrids, Affective Clones and Whatever They Want’, a body of artistic processes that took shape back in 2018, during my studies in New Media at the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb. In the three years since, the digital landscape has undergone an accelerated transformation. Posing as influencers advertising fast fashion brands DAZ3D digital avatars have taken over Instagram. Meanwhile, everyone and their grandmother has turned into a 2D video by #distantdancing on TikTok inbetween ZOOM calls. Presented here is a text which served as a companion peace to 'a performing site for affective clones & whatever they want'. Wanting to invert the (dominant) Gestalt of the animated figure, a specific type of digital image, the text maps the processes of imagemaking, animation, choreography and somatics.

1. INTRO

say: ‘I am a body’

stopping separation of

‘I have a body’

myself is a body:

a mebody

and the figure in the image

the body of the image

the image itself

could be

another body

a body of another.

the other?

One of the main elements in my work is the figure of a mebody often accompanied by a collaboratorbody – many times a dancer, a performer, an affective worker. Often (the) webodies are mediated by some type of image technology, so that what is addressing the audience is not just a body but its recording, an imprint, a trace, its interpretation in different stages of enacting or performing. As an action or a task, I understand performing to be a form of affective work.

But us webodies are not the only performers and affective workers at play. The ‘performing site’ is shared with other figures such as digital golems, gesticulating hybrids and affective clones – three types of anthropomorphic figures created by and coming out of 3d animation software. These 3d figures, these images, are always in relation to me or to us. They the intangible bodies are always in relation to us the palpable bodies.

My experience and practice of a variety of somatic approaches to movement, which move from within instead of fulfilling or adjusting from outside, has significantly changed the way I think about the body. And the body I am talking about is not only the body that moves around the room or adjusts its posture while sitting in front of the screen writing (translating) this text, but also the bodies drawn with charcoal on paper – by me and my art school colleagues during endless life drawing classes. The body which we made walk, whose hand we rotated, head squished, belly squashed – during our traditional 2d animation classes. In Art History lectures we were told and learned that this body is not real, it is only a representation. An image which we, the animators, need make convincing by meeting certain conventional, academic standards and forms.

Instead of identifying with the image, Hito Steyerl proposes a tactic of participating in the image. Though, unlike Steyerl, I do not disregard the weight of representation held by images (a cat.gif and a statue representing Croatia’s first president, autocrat Tuđman are not the same thing), I find it plays a secondary role. In my practice, they, the images, have stopped being symbols or a means to an end. Made of crystals and electricity, animated by our wishes and fears, embodying their own conditions of ‘existence’ with their intangible bodies. Images are not just a representation of ‘reality’, they are, in Hito Steyerl's words, 'a fragment of the real world. They are a thing like any other, a thing like you and me.'

1.1. DANCE AND CHARACTER ANIMATION

What do animated characters need?

With what kind of movement can they answer that need?

As part of the entertainment industry, traditional 2D animation perpetuates the production hierarchy inherent to the protocol of the film industry, like any other production of narrative and commercial animated content, be it a feature film or a cartoon series or any other format. Thus the traditional animator, following the vision of the director, assigns the keyframes to the characters. The spaces between those keyframes will be filled by some hunchback inbetweener, an animator from India, South Korea or the Philippines.

Traditional theater, opera and ballet are shaped by a similar structure. In a ballet each movement embodied by the members of an ensemble is dictated by the ballet’s choreographer.

The directors of both ballet and traditional 2D animation insist on controlling the form (and form is control). In Disney’s school of traditional 2D animation, the characters are outlined. The black outline keeps the figure’s volume constant while the character’s shape is subjected to linear perspective (Cubitt, 2014,). The body permeates throughout the carefully calculated keyframes, stretching and squashing, as if following the movements dictated by a ballet choreographer at a rehearsal. 1,2,3 – 1,2,3, – 1,2,3,-4,5,6, – moving through his preplanned dance phrases made of calculated steps and movements. Being a part of a sequence. Set in a scene.

Although this hierarchy of choreographer>dancer is still very much alive and kicking even in the realm of the contemporary-dance world, it has been challenged by a number of practices based on a (more) horizontal collaboration. Plazma is one such practice. Founded by choreographer and researcher of playfulness Curio Kitheca, Plazma refuses to depend on existing movement patterns. Instead, it is a physical training/game with a single task at its core: ask yourself the question ‘what do I need?’, answer it with movement.

Since both character animation and dance share the same basic elements (body, movement and choreography), I wonder how animated characters would move if they asked themselves what do I need?

1.2. ACADEMICISM AND THE SURMINUS OF ERROR

Throughout much of my education, starting at the School of Applied Arts, continuing through a short stint at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Skopje and throughout my BA at the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb, I experienced a mode of classicist/modernist thinking still very much thriving in those contexts.

During this eight-year-long training in depicting the human body and other objects from life, I was never too keen on realistic drawing, be it academic realism or photorealism (usually referred to by my teachers as ‘kitsch’). I found the tendency to convincingly mimic the object’s appearance interesting albeit naive – an attempt to make invisible the building matter of the image. Erasing the medium.

In the discipline of academic drawing, the draftsman’s exhibition of knowledge in human anatomy as well as the presentation of an apt comprehension of the rules of composition and other visual elements are of the highest importance. The result is always evaluated in relation to what is being depicted. Around a thousand hours of life drawing classes, measuring proportions with a knitting needle or a pencil, should result in the ability to contain within a 2D surface the strength of the body standing in counterpoise holding a rod, the ease with which that body slacks on the chair, the frailness when it lies on the floor with one knee up resting its head on an arm. Using charcoal to transfer sensitivity from the body to the paper, the drawing is meant to convince its viewer of the body’s existence. The draftsmen are meant to resist any caprice to augment, diminish, stylize or abstract the seen. For the life drawing classes are here to train my eye, my gaze – a signature style is to be gained by 'forgetting' the acquired knowledge, or as my teachers put it: lock everything away in a drawer and take a peek only when needed, but, first of all, of course, graduate! And though this modernist approach might sound like a retromorph, in many life drawing classes it thrives. The very same professors later took part in the monumental themepark of academic and neoclassical imagery – the Skopje2014 project.

This highly regarded form of academic easel drawing found itself juxtaposed to a form most popular amongst my male colleagues – drawings made by imitating the logic of a photograph. No matter the surface, be it a sheet of packing paper or lined paper from a notebook, everything glistened from the finger-smudging technique simulating the glossy surfaces of a car from the near future, a pinup of a woman on a beach, a celebrity or a lion. No matter the object, the strategy was always the same: trace or copy from a printed photograph, do your best to hide the fact it is only a drawing and do not be bothered by the tutors’ disgust.

What captivates me most in these copies of copies and academic drawings and in the monuments imitating the style of western sculptures from the Skopje2014 project, is the error. The ‘mistake’, which is recognized as such from the point of view of an authority evaluating representation by its successful mimicry of the represented object’s appearance. I am not talking only about a single slip, but a series of deviations in the display of the object’s representation which are the result of negligence and lack of the ever-so-desired skill. I am thinking of incorrect proportions, awkward linework, crude shading, accidentally over-pronounced elements, etc.

Attending the Faculty of Fine Arts in Skopje, I would often find myself slightly amused over these images, when the fact that these omissions are not the draftsman’s (or painter’s, or sculptor’s) decisions would be apparent. This amusement, or rather a bewonderment was over what I recognized as a sort of surplus, or better put – a surminus. A crack. A fracture in intention. What this surminus of error produces is a distancing effect. A Verfremdungseffekt acting as an echo. An echo of an image addressing me. An image wanting me to become aware that she is just that – an image. I imagine this as a magical insurgence. The object breaches through and mocks the act of representation. Representations declaring their independence. Declaring their otherness. The disproportionate extremities and rigid curves of Alexander the Great’s or Olympia’s dress cast in bronze, a flat Ferrari with fire patterns or the plastic woman on a beach in the 2B pencil pin-up distort their author’s projections, and reflect back to me. Back at me.

They shout: ‘I am something else! I am something other than!’

2. DIGITAL GOLEM

I devise the material for my performances through improvising – using open scores which allow for free organization of pre-established elements yet leaves space for novel materials to emerge. Tweaking the rhythms and intensities, shaping a porous whole through time.

In the realm of performing arts, more specifically in the realm of ‘contemporary dance’, improvisation is a basic tool for generating content. Improvisation practices continuously go about answering the question of what is improvisation by improvising.

Next to improvisation practices there are also somatic practices, which simply put are bodily practices, a field of researching body-movement through inner perception and sensation. Different from dance techniques like ballet or modern dance where movement is sculpted by an outside gaze, somatic dance techniques focus on movements structured and interpreted through proprioception – awareness of the position and movement of the selfbody.

The first performance in which I tried to translate the workflow from a software interface onto the self body, time and space, focused on Andy, a premade figure appearing in the popular 3d animation software Poser. I also incorporated free premade 3d objects from various resources which doubled whatever object was present in my working studio at the time.

Imagine this:

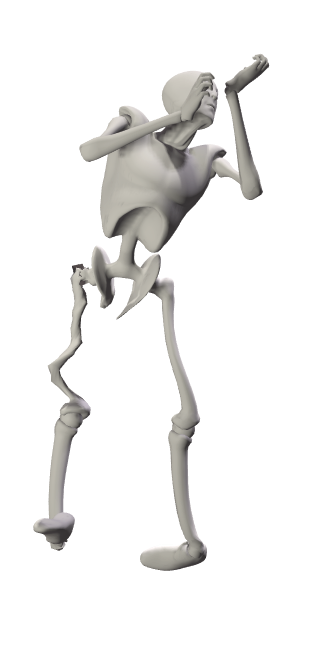

Just after you’ve installed a copy of a 3D animation software you are completely unfamiliar with, you are greeted by a skeleton.

Andy, a didactic mannequin, is looking at you through a grin so sticky it remains unchanged, glued to his face no matter how hard you translate or rotate his wrists, ankles, pelvis or head.

For the fun of it, you try loading other objects in from the left – I mean right corner of the window.

Your right, his left.

But instead of sitting on the chair Andy phases right through it and the chair floats away.

Both remain suspended in space, unbothered by the pace at which the Main Camera rotates.

So fascinated are you with what accrued in an hour’s play that you press hard on your own chair until it – as a byproduct of both your weight and clumsiness – falls on one side by which you only try avoid hurting yourself yet remain stiff.

Locked in a liminal position. Frozen in a still frame.

I recognize default, premade and already available 3d models as Digital Golems. The Digital Golems have a pedagogical purpose: to familiarize the animator newbie with the software basics. The animated anthropomorphic being from jewish mythology, the Clay Golem is their palpable ancestor. In most versions of the myth, a rabi awakes the golem from mud, controlling it and using it as a shield against enemies, but this mythical Golem having fallen in love and being denied this love, goes berserk. With its purpose lost, for the rabi can no longer control it, with words he turns the Golem into dust.

The materials from which the Digital Golems emerge are pixels, dots of colored light. Approximations. Abstracted volume sometimes appearing to be thick rubber, sometimes shining as though it is a glass full of milk. Once the animator newbie has mastered the basics, The Digital Golem becomes obsolete – forgotten or even erased from the software’s content library.

Andy or Mannequin Andy or MilkmanAndy is the default figure haunting every New Scene in Poser. File > New > New Scene. Andy’s creator, signed as ANYMATTER devised his design from skeleton sketches found in the popular human figure drawing manual by Andrew Loomis Drawing for All It’s Worth – which happens to be one of the manuals used throughout my education. Andy is also a pedagogical tool, a preparatory tool to test and learn basic animation principles like the walk cycle.

Andy is a commercial model. Andy isn’t free.

Curious to explore physical borders of bodies, I started by moving the Andybody and creating different animations in which his extremities swirl in circles dragging what’s left behind in a bundle of extruded polygons. Applying experience from the seen, I tried applying some of its principles to myselfbody. I was less interested in the general topic of the physical abilities of human bodies. Instead I focused on what was being produced by physical limitations. What affects appear in the rhythm in which I, hunched animatorbody, without concrete physical skill or discipline attempt to quickly move and stop. How does that movement relate to the clumsy animations of Andy’s dance?

In this performance I consider myselfbody as parallel to Andy. Is Andy empty? An empty body? A body without organs? A hollow body. A body through which other bodies pass. A bodyobject equal to all other objects present in the space. Equally still, static or suspended in space a glass bottle. Polygons slowly decomposing, Andy slips through the ground, from which only a few frames later he emerges intact as a levitating cardboard box phases through him without leaving a trace. All this in an endless loop.

In the software categories Andy is labeled as a body, but any object transfers to the body category as soon as it gets rigged. As soon as an invisible vector skeleton gets inserted in it.

Once the hunched animator has mastered the basics of Poser, Andy becomes superfluous. He will be replaced by another body from the content library. A body which sole purpose isn’t to be a dummy, a caricature, a simplification. A body which faces us and says : ‘I am real.’

The golem is haunting us. It is trying to tell us something

[...]

Perhaps we need to listen more attentively to the golem’s massage.

The most remarkable thing about the golem in many of its modern versions is not its instrumentality or brutality but rather its emotional neediness and capacity for affection. The golem doesn’t want to kill, it wants to love and be loved.

Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt, Multitude (2004)

3. AFFECTIVE CLONES

3.1. DAZ3D and GENESIS: Hybridizing the readymade as cloning

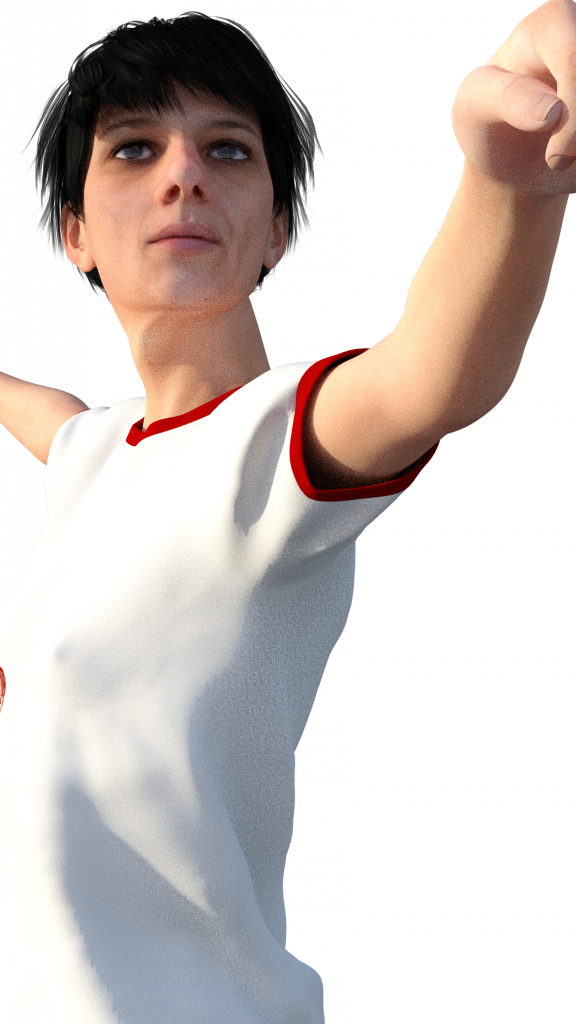

I invited two friends, Ivana Rončević and Ana Jelušić, both dancers educated in somatic techniques, to collaborate and perform in my graduation piece.My wish was to re-apply some of the principles I had established in my earlier work, where performative situations were devised from improvisation sessions where movement material was transferred to 3D software figures, and then both were used on site.

Instead of using Poser or Andy, this time around I wanted to deal with different software and figures. As an alternative to Poser, Daz3D is extensively used in both amateur and mainstream movie production, most commonly for special effects (SFX) that include bodies of actors in situations that would otherwise destroy the human body. As a replacement for the real actor, Daz3D introduced Genesis, a readymade figure whose purpose is hybridization. Within the software, Genesis is an actor – a model that serves as a platform, a template for creating other, ‘original’ characters. Made as a polymesh, Genesis’ body and likeness can be transformed simply by moving morphs, and be shaped to take on another resemblance or difference.

We hybridized Genesis and made several replica’s of ourselves – digital clones wearing a photo of our face, covering their own. Via a beamer and two LCD screens we introduced them into our studio and rehearsal room. We took some time to discover and start understanding their physicality, alignment and anatomy. Noticing differences and resemblances, playing around with various types of movement, AnaG3, AnaG8, IvanaG2, IvanaG8, MarkoG3 and Marko G8 became our collaborators in the everyday affective work of movement improvisation.

PROTOCOL FOR CLONING THROUGH DIGITAL HYBRIDISATION OF READYMADES

(1.)

Take a flash photo of your face in an interior.

The whole face, including the forehead, needs to be clearly visible.

Take three photos per person.

(Three for Ivana, three for Ana, three for Marko.)

En face, left profile and right profile.

(2.)

Export photos to FaceGen

Mark the placement of the nose, the ending of the lips, the protrusion point of the chin. When FaceGen is done calculating and generating the 3D polymesh of your face, export to DAZ3D. Be sure to select which model the mesh needs to be adapted for: Genesis, Genesis 2M, Genesis 2F, Genesis 3M, or Genesis 3F.

(3.)

Load Genesis figure of choice into Daz3D scene, and go to Shaping>Genesis 3 Male>Actor>Head>Shaping. Take slider showing < name> from 0 to 1 to make Genesis face resemble yours.

Adjust figure’s chest, waist, height and width.

(4.)

The textures for face, ears, lips, torso, arms, legs, nails, toenails, pupils, sclera, cornea can be adjusted under Surfaces>Edit>Genesis 3 Male>Surfaces>...

Change diffuse, normal, bump and surface scattering values and textures to the ones generated by the FaceGen algorithm by adjusting and comparing the color and shaping data from the photos with ones from the FaceGen database.

3.2. MIMICRY and Convincingness

With just one side and one margin, Ivana G2, Ivana G8, AnaG3, Ana G8, MarkoG3 and MarkoG8 resemble the Klein bottle or a Möbius strip. As if there is no inside or outside, the polygon-made bodies dance along the pixels of my LCD screen. The everlasting negotiation and transfer of information between my GPU and CPU. The polygons of your polymesh upon which a variety of textures and properties are stretched and skewed take the appearance of the organic only when shot with the ray from a point of view of a hypothetical camera, analysed by the rendering engine which processes you into a photorealistic form. A form in which I recognize you.

When someone else describes an image as convincing, I take it as a statement that the difference between the represented object and its representation are minimal or that the intentions of its author are deemed trustworthy or successful. On the other hand, when I say a picture is convincing, I mean to say that I feel that the image is trying to convince me of something. A persuasion. But whose? The author’s? Is the author of the image commending it to persuade me or is she doing it by herself? Computer Generated Imagery (CGI) is used in the entertainment industry to fill in the cracks in tangible reality created by the desire for something more. The aim is to create a striking, convincing picture, in which the geometry covered by a stretched texture simulating certain material, is hidden with the help of various techniques simulating physical light. The persuasive aim is an image in which the noise that makes up the image becomes unrecognizable as a cluster of dots.

Paraphrasing Freud, W.J.T. Mitchell’s question What Do Pictures Want? recognizes images as subjectivized objects: ‘things that have been marked with all the stigmata of personhood and animation: they exhibit both physical and virtual bodies; they speak to us, sometimes literally, sometimes figuratively (...) They present not just a surface but a face that faces the beholder.’ A face facing us, addressing us, wanting something, wanting to convince me of something – but what?

Mimicking the outer appearance of the depicted object, trying to mask the fact of its imageness by covering the trail left by the technology of its own making, the picture insists on being recognized as an equal. As ‘real’. She lays claim to realness. Inherent to her claim is the danger that, in the case of failure, she will end up in the recycle bin, discarded by her author or mocked by her viewer. Overlooked by the lot. In the case when this image is that of a Daz3D digital actor, she is threatened by the possibility of forever being left on the dusty shelf at the Daz3D online store. It is precisely because of this that the image is prone to act as if she is more than ‘real’: she is more beautiful, more exciting, sublime. More than this reality – she is beyond this reality, in fact she is part of another reality in which, by her author’s decree, she is forced to convince us. Her act of mimicry is an act of self-defense.

In my work, I do not like to cover up the fact of imageness. It is clear that IvanaG2, IvanaG3, AnaG3, AnaG8, MarkoG3 and MarkoG8 are animated images. They appear in different stages of rendering, in different resolutions and image quality. Sometimes they are blurry, appearing as unclear clusters of noise, never enough to make crisp shapes. From afar it might be easy to mistake them for photographs but take a better look and they will reveal themselves as CGI bodies, their flat bodies doubling on top of each other. Our clones are shaped within the technical limits of Daz3D and left .RAW (without post-production make-up): limited body-shaping capability, pre-made hairdos which are not integrated parts of the head but wig-like .obj-files (like the wardrobe), different anatomical accessories, and simplified movement sequences.

In ‘Vital Signs / Cloning Terror’, the opening text of What Do Pictures Want?, Mitchell defines clones as copies, replicas, surrogates, doubles, but also as biological simulacra of living organisms: ‘Clones just want to be like us, and to be liked by us’. Mitchell points to anthropologist Michael Taussig’s view that the strategy of mimesis in traditional as well as contemporary society is not the mere production of the same but a mechanism for creating difference and transformation: ‘The ability to mime, and mime well, in other words, is the capacity to Other.’ A capacity for Othering.

The word for ‘other’ in the languages of ex-Yugoslavia is the same as the word for being second, but could also mean being a friend or comrade (‘drug’). ‘Othering’ then translates as ‘drugovanje’, which means friendship or comradery. Drugovanje is the basis of how I understand my practice: a camaraderie and friendship based on the difference between them impalpable clones and us palpable performers as well as differences beyond the amount of palpability.

3.3. A PERFORMING SITE

In getting to know our clones, we spend time contemplating, experimenting, and playing around, translating the digital physicality and the movement of digital bodies whose purpose is to simulate ‘functionality’, onto ourselves. Translating the emptiness, vectors, joints, and other qualities through embodiment tasks, in an interchanging rhythm, we come and go like this: first their take, then our take on theirs, then again their take on our take on their take ad infinitum – all the while creating a common spacio-somatic knowledge, which then again differed for each of us. A movement of a hand, or the feeling of a hand moving through the chest uninterrupted so that it ends behind the back means one thing to me, a different thing to Ana, or Ivana, or IvanaG2, or MarkoG8. Interpreting this exchange of movements was not driven by the desire for representation, but by the desire to generate curiosity for continuously being present in exploring the feeling of one or another movement. Feelings of resemblance and feelings of difference. In motion, in dance.

Yet the desire to find a possible place of contact, co-existence and co-creation between me, Ana, Ivana, myself and our clones, went further than just experimenting with what could be understood as pure ‘movement’ material. We spent some of the sessions submerged in ‘deep time’ where everyone for themselves attends and listens to the impulses, sounds and changes within and without, suggests movement or a frame of view by gazing, watching, making sound or silence, mapping that which has happened or bringing back something which lasted only briefly.

Working in a spacious studio, we concentrated on its depth which provided a huge unperforated white surface for the clones to be beamed on, enabling them to exit their depthless abstract space in ‘full size’ by occupying the space of the back wall. The other walls were in pale yellow and in some places they were filled with holes and markings from the concrete filling covering the cracks. There are various names, telephone numbers and other signs scribbled on them. The only windows, facing south, are covered with black curtains, and originally the room hosted a ladder, a speaker and some chairs. As mentioned, to be able to have physical contact with the clones we installed a beamer accompanied by a laptop and two LCD screens. Through the screens the clones were able to move around the space. They could go up or down, closer to the windows, or a bit further, closer to the door. They could lie down on me, they could sit in front of me, they could take a look behind me.

We brought sheets of paper of different sizes and formats, which we sometimes folded and organized throughout the space. We did this also with other objects we found in the space. Sometimes we would have fruit: a banana which Ivana and me would split, a mango which Ana would squish after she was done playing with it. Sometimes we would have other food like chocolate cake. Oranges would be carefully peeled for a duration echoing Ivana’s action of slowly connecting different objects in space with duct tape. We tried to divide responsibilities proportionally: to the clones we left more space for movement, whilst we dealt more with embodied presence, relations, actions and interactions with objects through which we tried to unpack and understand different states which we recognized in the digital clones. Me, Ivana and Ana were occupied with the inside of the performing space, the interior of the performing site, whilst the clones carried out the work of bodily expression directed towards the outside - towards the viewer.

Even though they are ‘merely’ an animation, our clones are not cut with the logic of the film shot, but with another type of framing. Their presence in the projection and the LCD screens is contoured by us, bodies, and our actions. What is focused is not only the content inside the screen, but also outside the screen: what is the relation between the outside and the body moving inside, and how does that relate to the body witnessing this interplay? Sometimes from afar, sometimes up close, sometimes in front and sometimes from behind.

The change of light also plays a role. There is a neon lamp. The curtains covering the only source of daylight are lifted slightly by us or by a breeze every now and then. This change of lighting directly affects the visibility of both the clones and the light frame of the beamer. Erasing this frame, which separates the digital bodies from the rest of the space, the flat body mixes in with the surface and reverses the Gestalt with its contours resonating with the other bodies and objects in the space as something present both ‘in’ and ‘on’.

In the space and on the surface.

3.4. AFFECTIVE WORK

What is created in the networks of affective labor is a form-of-life

In his 1999 text ‘Affective Labor’, Michael Hardt conceptualizes affective and intellectual work as two faces of immaterial work. Referring to existing theoretical frames (mainly marxism, psychoanalysis and feminist theory) in which the idea of affective work touches upon terms such as desiring production, kin work, caring labor, Hardt contemplates affective work and its change within capitalist economy. For Hardt, affective work plays a role across a wider field of service industries – from the staff in a fast-food joint to the one at a bank desk, or health services to which care as a form of affective work is central. Although affective work has never been outside of capitalist production, Hardt thinks that with the process of economic postmodernization, which he also calls informatization, affective work comes on top of the labour hierarchy and becomes the dominant form of labour in privileged and so-called developed countries in the economy of global capitalism, affecting all other types of production. Postmodernization or informatisation is what Hardt calls the transition from a paradigm of modern industrial production into a production of knowledge, information, communication, relations and emotional reactions, namely immaterial labour and service jobs.

Almost every type of immaterial labour, Hardt says, has an intellectual aspect – the production of information, exchange of symbols and generation of knowledge (analogue to digital operations even when there is no direct contact with computer devices), and the affective aspect of human encounters and interactions.

Although intangible and often short lived, outcomes of immaterial production always include our bodies. Efforts of immaterial labour are still material, and even though embodied, products of affective work are intangible: feelings of easiness, wellbeing, satisfaction, excitement, passion – even a feeling of belonging to a community. Hardt reflects on the fact that many of the mentioned types of services are practiced in person and it is exactly production of and manipulation with affect which proves essential for Hardt in the one on one encounter. Just as it is in theater, or ballet or in an animated feature or some other branch of entertainment industry, the actor, the dancer or the animated character uses her body, movement and voice to relate with the other – the audience, producing affects. And though this encounter between the performer and the audience is principally virtual, says Hardt, it isn’t any less real.

We read the projected figures as unreal, imaginary, fake – made artificially, with a computer, made digitally. They are also unreal because they are in continuous contrast with us – the real ones. It is through our contact – mine with Ana and Ivana’s with me and MarkoG3’s with Ana and AnaG3’s with Ivana and Ivana G8’s with Ivana G2’s and Ivana G3’s with AnaG8’s or any other possible combination, that an affirmation of different materialities emerges in an exchanging rhythm between the affects of our tangibility and their intangibility, creating a reality in the shared affective space of the performance.

By themselves, the clones are closed up in the medium of animation. The medium of animation like other work with images (in the traditional sense), has a tendency not to be explicit about its making. It tends to hide the affective effort put into it, except in cases when the author decides otherwise (which often ends up being a representation of the working process). When sharing time with me, Ana, Ivana, AnaG3, AnaG8,IvanaG2, IvanaG8, MarkoG3 and MarkoG8, coming closer or distancing ourselves from one another, in the gaze of the spectator we become an image. We are at the same time a product of affective work and affective workers.

Getting closer together, falling further apart, webodies moving, webodies watching, webodies sensing, caring for the image, allowing it to change us, changing the flow with our assembling and rearranging, as it is inherit to it, our performance emerges in front of its audience. The audience is a witness to this process as well as a participator in this soft exchange with her physical presence. Sharing the space and time of the performance, its becoming, its unfolding, its duration.

Lying on the floor.

For about twenty minutes.

You realize your breathing rhythm separates you from them, try to calm it down.

Focus on the peace which is already present in the room. It is present for them too.

Ana slips behind the curtain and looks out of the window.

The black material covers her from the knee up. She picks up the curtain and lets the light in.

A splatter of light hits the back wall where AnaG2 makes the transition from an arabesque to a bridge.

You get up and walk to the LCD screen on the far right. Enter IvanaG3 looking in the direction outside – or is it behind the frame of the screen?

With a frown she turns back to us.

You lower the screen and let it lean to the wall behind you where the other Ivanas, IvanaG2, IvanaG3 and IvanaG8, are constantly moving and shifting in order to fill out the space.

IvanaG8 moves on all fours from one end to the other, cutting through IvanaG3, balancing in front of a giant MarkoG3.

Also on all fours, Ivana takes time to notice the sensation of a slight rotation in the upper vertebrae. She gets up. In response to the dance of the other Ivanas, she decides to find an object and disperse it throughout the room.

The fact that the white-and-yellow paper is of a similar shade as the the walls in the room is noticeable in this half-darkness, she thinks, and shifts her attention back to scattering the sheets of paper.

Ana, mirroring the poses in which the Ivanas are now resting, dances out a sequence she saw somebody do earlier and covers the projection with her back.

Climbing her shadow whilst it enters their space, they settle on her shoulders.

She becomes a place.

What happens when we swap?

If you’re doing that, can I do something else?

Here,

You dance,

Smile whilst looking at them,

I’ll sit,

Reposition things in space,

Move them around,

Arrange them,

Try to organize,

Tidy up,

I’ll imitate you for a while.

Then you will start imitating me.

And while I move around I’ll try to sense how it feels to be you imitating me imitating you.

And then, together

We rest for a bit.

I follow you around

with my eyes.

You’re in joy

I am also rejoicing.

And then, one more time.

Find a place,

Find an action.

Notice.

Insist.

Release.

Repeat.