Assemblages of screenshots from different internet resources

We must know whether we want to change the world to experience it with the same sensorial system like the one we already possess, or whether we’d rather modify our body, the somatic filter through which it passes.

Testo Junkie, Paul Preciado

Day 15 - The Number One Enemy

I woke up earlier than Juli. It’s day 15. The fog is slowly appearing around me. I don’t see it, but I feel and hear it. It is this silent cynical voice within my head telling me that every attempt is worthless. It is the slowly escalating anxiety rushing through my veins when I start focusing on what could go wrong. The sun’s rays are piercing through the mosquito net. Juli is still sleeping.

How do people do it? How can they do it?

The image of my parents rises in my head; the stupid idea of their monogamy and the concept of sleeping in the same bed every night. I remember thinking that doing something else would be the ultimate proof of being unloved. This thought on endless continuity and consistency feels like a weight, a terrible pressure. I sense it pouring all over me, laying in bed, covered by a light blanket and the sleeping arms of Juli.

In her book Illness as a Metaphor, Susan Sontag investigates the cultural and aesthetic representations of disease in society. She explains how they are often displayed as images and meanings, instead of being seen as what they fundamentally are: a burden and a condition to be treated.

When I started researching Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder, I read the list of symptoms first, to see what the condition entailed and to see how a diagnosis would be made. It was a surprise and a relief when I realized that the diagnosis was not purely a scientific one, but rather an empirical one. Still, I wondered, how does one treat a condition as a disease, when it is, in essence, seen as a fundamental component of our lives? How to approach an experience that has been understood and studied for so long as an unavoidable and fatal component of our bodies?

Before it was even categorized as a disease, PMDD existed as a metaphor. Nowadays, it is the symbol of our bodies’ treatment and the prejudices around it. More than a disease, it is the result of our limited understanding of the influence of hormones on our body, psyche, and our social life. PMDD is the impact on how one’s body is reflected in society. It is only once we understand the role that this metaphor plays, and how it limits the possibilities for treatment, that we can understand what is at stake behind the acknowledgment of such conditions.

Irritability, Nervousness, Lack of control, Agitation, Anger, Insomnia, Difficulty in concentrating, Depression, Severe fatigue, Anxiety, Confusion, Forgetfulness, Poor self-image, Paranoia, Emotional sensitivity, Crying spells, Moodiness, Trouble sleeping, Abdominal cramps, Bloating, Constipation, Nausea, Vomiting, Pelvic heaviness or pressure, Backache, Decreased coordination, Painful menstruation, Diminished sex drive, Appetite changes, Food cravings, Hot flashes.

One of the first questions that come to mind when reading this list is “Whose menstruating bodies do not suffer from those symptoms?”. Surely, the severity of those and their frequency may vary from one individual to another. PMDD is a floating cloud that englobes an entire field of dysfunctional behavior and physical incapabilities. If you menstruate and feel terrible two weeks out of four, it’s quite likely that you have this condition too. It is difficult to diagnose and treat it, specifically because the symptoms can be so diverse. As far as scientific knowledge goes, it is generally understood as a dysfunctional reaction of the body from the changes of hormones throughout the month. These symptoms usually disappear at the beginning of each cycle, when menstruation starts.

It is complex to study PMDD as a real condition because it regroups all of the symptoms that, individually, can be dealt with, but as a whole, can make it impossible for any human being to function. It is too complex to understand the severity of the problem in a society where menstruating bodies have been conditioned to think that pain is normal, and that menstruating is a curse that we have to learn how to deal with in silence. A body suffering from this condition can hardly express its feeling to a society that has digested that it is a normal narrative to suffer when you’ve been cursed and born with a uterus for centuries. The data collected demonstrated that 20% of menstruating bodies deal with PMDD; approximately 600 000 000 bodies. PMDD is a fluctuation that, perhaps, one could deal with if we existed in a society that did not value endless efficiency or competition If we lived in a world that did not see our uteruses as constantly available objects, if fair rates in the working environment were a thing and if generic medicine tried to look into the causes and not the symptoms. PMDD is one of the many diseases which is not understood (yet) because there's no interest, no lobby (yet). It is one more phenomenon, one demonstration that our world and systems have not been designed by other than men.

Those who suffer from this condition are moralized not only by the medical field but also by the people surrounding them. Perhaps their mental confusion is understood as hysteria, their low libido is seen as a lack of love, and their frigidity is a mystery. Perhaps their fluctuations are seen as bipolarity and their emotional unsustainability as craziness. There should be no confusion about the fact that PMDD is a condition, a disease, and a dysfunction. Like for many other diseases, its effects are highly enhanced by its unrecognition, by the absence of knowledge on the subject, and by its confrontation with society’s norms. While it is still hard to know and tell where the condition comes from, what triggers, and what exacerbates it, using PMDD as a metaphoric condition enables a lens to look into the technologies of menstruating bodies and the advancements designed for them.

Over the course of the past century, enormous breakthroughs and progress have been made in the research field of menstruating bodies and female conditions. The era of the mystery of blood and burnt witches is, thankfully, is long gone. Although this does not mean that the gender bias in medicine and in research has been resolved. The majority of studies look into conditions from a male perspective and generally, women’s studies remain poorly funded. Luckily, multiple books about menstruation and female reproductive organs are currently being published and the knowledge produced on these matters is ever-expanding. As we now have the chance to look into the depth of, the history of and functioning of our bodies, we are presently given the chance to better understand the mechanisms of power and oppression behind this technological progression.

The Insufficient Technology of the Body

Menstruating bodies and technologies have an ambiguous relationship. Firstly, the ability to be fertile and give life remains one of the biggest possibilities of our existence. Menstruation, the absence of menstruation, as well as the many fluctuations coming throughout our cycle, are technologies that enable us to be aware of the self and of our environment. This very specific aspect of our bodies is a fundamentally political tool, and because of that exact same reason, we have been offered many assets, pills, supplements and devices, under the concept of progress, to help our bodies function better.

As a human-lived technology, the body fluctuates and sometimes does not offer the best living experiences. Not all menstruating bodies menstruate or have a regular cycle. Not all of them ovulate or can conceive. Some struggle with intense pain, some never experience pleasure. To live with your biological condition does not mean living a better life. The technology of our bodies can sometimes affect various areas of life in quite unpleasant ways. In regards to female bodies, recent progress and discoveries have offered the possibility to offer us advancements and technologies to overcome pain, obstacles, failures, and many other conditions.

For the body's Accessibility, we’ve been given birth control. For the body's Reproductivity, FIV. For the body’s Longevity, hormones replacement. Body’s Mental Instability, SSR. Body’s Fluctuations, Health/Menstruating Apps… this list goes on and on.

While these technologies used to bring along a lot of enthusiasm in female and menstruating communities, perceived as tools for emancipation and freedom, they are now questioned and put in perspective with ethical, political, and ecological implications.

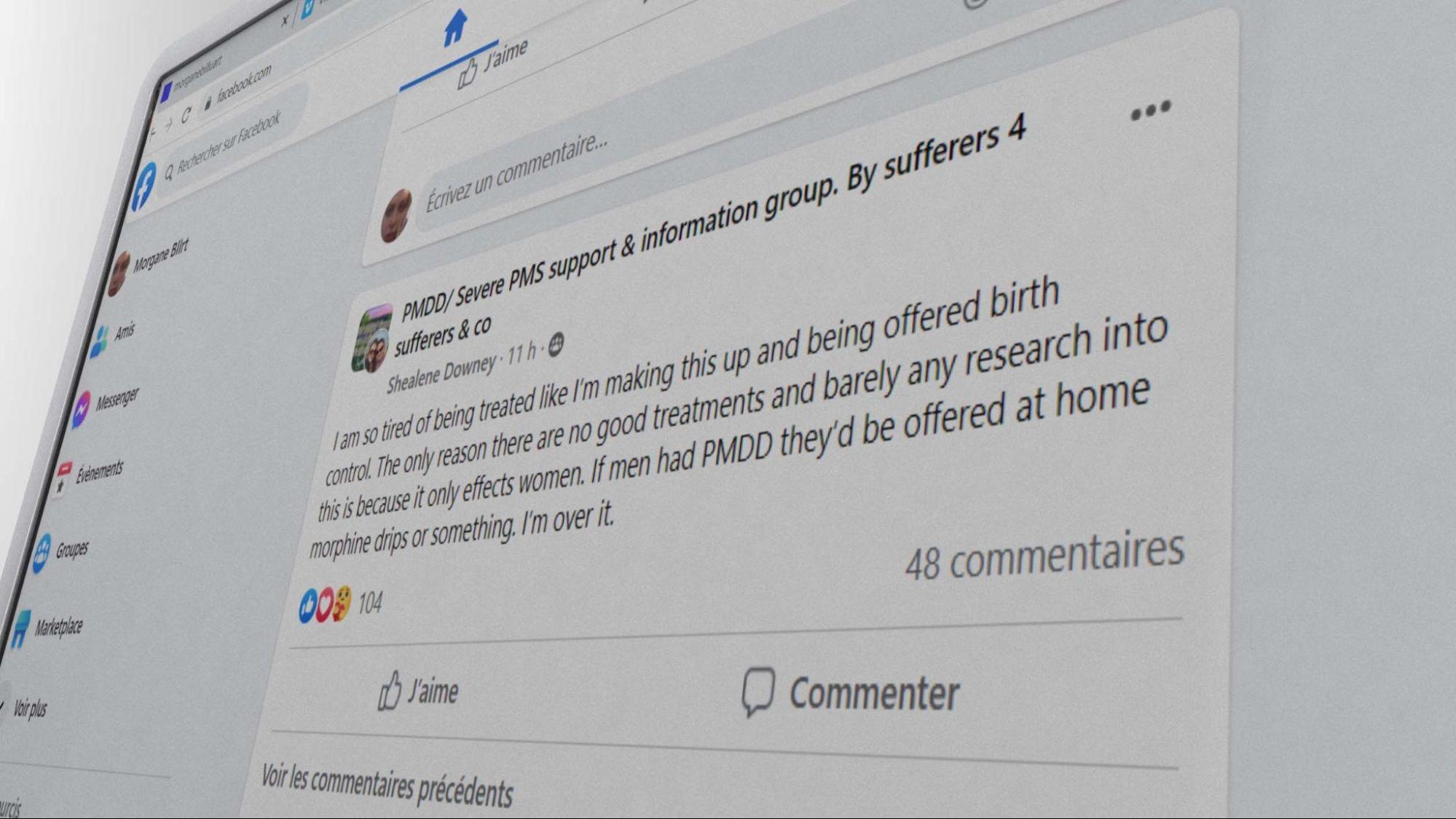

These rising communities, mainly perceived online, emphasize their indignations in regards to the consequences of these technologies and the remarks are generally about the lack of knowledge on the causes or implications of certain the conditions. This is particularly the case of communities of individuals suffering from Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome or Premenstrual Dysphoric Syndrome. Although these two illnesses are very much different, they both reflect a similar issue; the body suffers from its own technology, and to which the solutions provided are quite often not adequate. As a result of their feeling of being misunderstood, these communities meet and exchange their knowledge on alternative digital platforms.

Screenshot from the group PMDD/Severe PMS Support, post by Shealene Downey

Screenshot from the group PMDD/Severe PMS Support, post by Shealene Downey

Yes, science and generic medicine offered more comfort than pain in our lives. Although it would be too easy to pretend that the technological advances in the last century were only liberating and emancipating. By moving away from our biological conditionings, perhaps we were freeing the body from deterministic features and political constraints, however, the menstrual and medical revolution that we are now facing seems to demonstrate more complex dynamics. With or without the pill, with or without these conditions, our bodies are gradually realizing that the environments in which we evolve are not, by definition, designed for us. A problem that neither the pill, anti-depressants, nor this false political promise can hide anymore.

If these conditions are indeed a representation of our failed technology, recent studies which looked into the hormonal and social roots of PMS, universally known or experienced as premenstrual syndrome, demonstrated that its symptoms are highly impacted by the social environment one exists in. Researchers investigated how its effects changed depending on the social environment, demonstrating how menstruating bodies, when failing to be super-efficient and adequate, often failed into self-pathologization:

“When women were able to be alone, they reported that their premenstrual symptoms were reduced; the ‘PMS’ effectively disappeared, and they felt ‘better’. However, many of the women we interviewed never took time out for themselves in the whole month, and spent little time engaged in leisure activities, focusing instead on the needs of others, common to women who present with ‘PMS’ clinically .”

These perspectives on the subject matter invite us to wonder: what is it that makes these bodies inadequate in the first place? What is the reference we’re looking into to determine how one should function? While the conditions we mentioned earlier (PCOS, PMDD, and others) are often grounded in physical and hormonal dysfunction, they seem to offer us a critical lens to look into how our technological bodies are perceived and function, what assets and advancements are being offered to us, and if these new technologies help menstruating bodies feeling better and heal within society at all.

In her thesis, The Genesis of Premenstrual Syndrome, Bianca Zietal reinforces the idea of PMS as a social construct by illustrating “how the concept of PMS was developed and informed by the discovery of hormones and the resulting field of endocrinology that provided a framework for conceptualizing PMS.” The researcher expands her theory and demonstrates that the metaphor of PMS illustrates its unrecognition: “This variety of uses suggests that popular culture understands PMS as something that makes for a good joke or serves to explain a negative change in a woman’s behavior. However, relatively few people know that PMS has an official place as a medical diagnosis.” It is specifically because we have integrated that mood swings, pain, or mental disability are a fundamental component of menstruating bodies' life so well, that, as a result, this universally known disabling phenomenon isn’t still properly addressed and taken seriously. By limiting the urgency and despair in those experiences, those bodies’ needs are repressed and they repress themselves in return.

Science alone won’t help us. To only call out hormones and biological dysfunction for being the entire cause of our displacement would be to refuse to see how societal constructs still play a big role in this issue. Through the lens of the condition of Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder, manifesting as an intense collection of PMS, we can ask, how this condition can help us reconfigure the technologies of our bodies and question the way that they are being taken care of in society? More than a chemical or hormonal imbalance, isn’t PMDD a metaphor for our body’s inadequacy? Could it also be the externalization of our incapacity to fit in the design of ideal efficiency, in the template of society at all?

Contemporary literature addressing the topics of women and mental illnesses is scarce. It is often written by women themselves, who, based on their own understanding and experience of their bodies and minds within society, started to ask questions. In her book, Women and Madness, Jane Ussher expands on how her mother’s condition drove her to study psychology and investigates the dynamic of the pathologization of women’s dysfunctionality. In this book, Ussher makes the following statement: ‘In an official announcement nearly half of all American's experience a psychiatric disorder. Does that mean no one is normal? Or do we live in such a crazy-making, sick, impersonal society that it does serious psychological damage to half of us? Should we be calling women the mentally ill or society's wounded?’ While this realization is a question that could be applied to a broad range of conditions and diseases, it is specifically urgent to look into how the criteria and expectations of our cultures can lead to the aggravation of those.

Upgraded and Updated: on Hormone Replacement and Alleviation

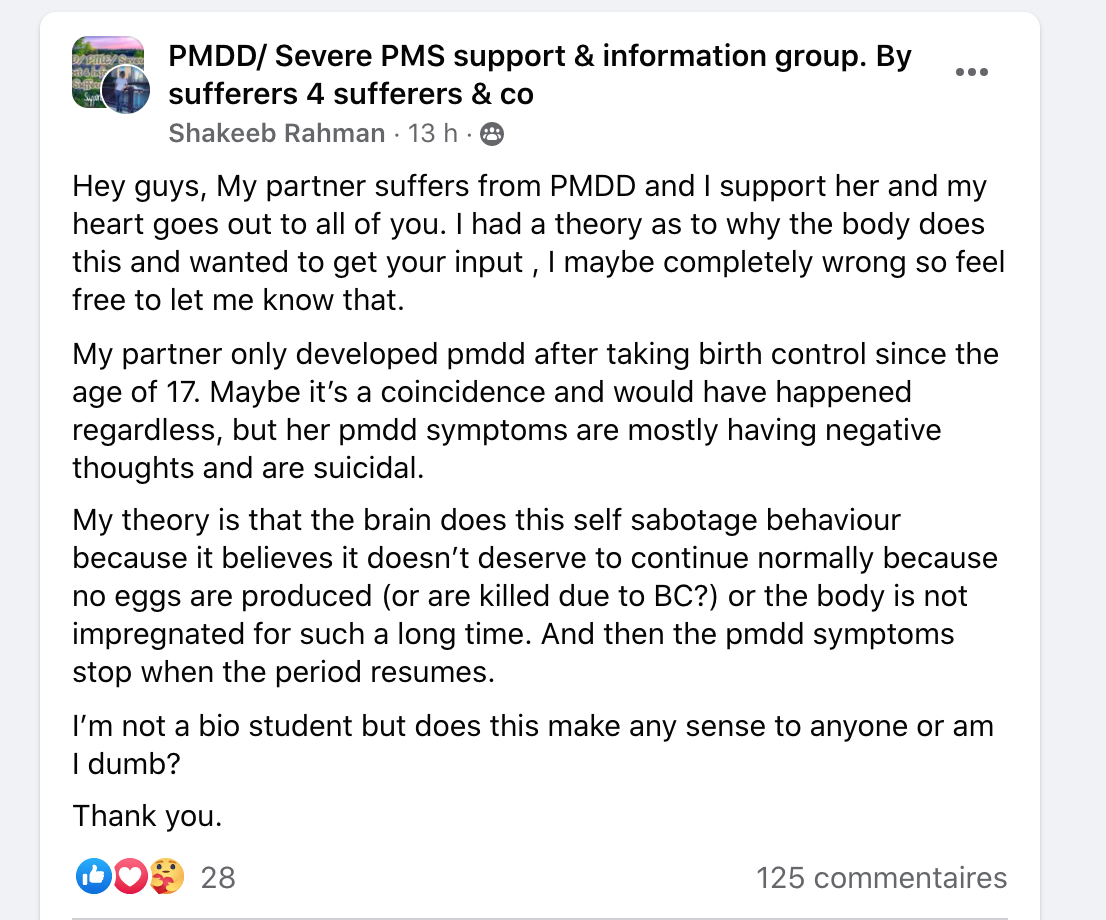

Screenshot of the Facebook group PMDD/Severe PMS support, posted by Shakeeb Rhaman.

Screenshot of the Facebook group PMDD/Severe PMS support, posted by Shakeeb Rhaman.

As previously mentioned, it is difficult and tedious to diagnose PMDD. Even though the condition seems to have been named for more than 20 years, institutes and research in its regard remain succinct. As a result, the production of knowledge and treatments are scarce and often reductive. PMDD being a disease with hormonal and psychological impacts, two fields of action are proposed. First: the pill, in order to suppress hormonal fluctuations and consequently, these impacts on the body, or second: anti-depressants, in order to alleviate the mental burden of the condition in everyday life. While these treatments might help some individuals and bodies by lessening the symptoms generated by the condition, it does not seem to change anything in regard to the urgency of the topic, as well as lack of knowledge around it. While our bodies are being offered pills and assets to cope with such conditions and what society made of them, there exists a risk of these conditions being under looked, perhaps even remaining unstudied.

In the article Fake periods, side effects, and other things you need to know about the pill naturopath Lara Briden explains how the number of solutions given to those bodies reflects the scope of knowledge around it. “At the moment, the pill is one of the only women’s health treatments available to doctors,” Briden says. “So, of course, they have no choice but to prescribe it for all manner of period problems.” It would not be the first moment in history that these bodies and the technology within are dismissed, put aside rather than questioned and supported. Therefore, it is urgent and necessary to wonder what will happen to our bodies and to these conditions if they remain hidden, unspoken. Are they veiled by the designed cure? What are the technologies proposed, and what are the implications behind these choices?

Day 14 - Memories of Diane 35

The perfect cycle’s length is 28 days. So are the number of these pills that I had to swallow. They say ovulation happens two weeks before menstruation, therefore, I should be ovulating by now. I used to feel it more intensely before. I noticed in the past how my behavior changed around that time. The texture of my discharges. The smell of my body. The look I give to men. Ovulation is, primitively, the key moment where one should conceive to have a higher chance to reproduce. My body knows that by now, but it was not always the case.

Summer 2016. I got prescribed Diane 35 to deal with skin problems and non-existent periods. I am pretty sure that my body is trying to tell me something, but I am 19 years old and I have no time to wait for my skin to be perfect and my cycle to function. These are early teens, or elderly’s people problems, not mine.

I remember walking in the street of Sicily with A. He gets mad because men look at me as if I was an object. Am I not? Diane 35 cleared my skin, made my boobs grow enormous and my hair grew thicker. It’s all I ever wanted, all of this potential in a small, ridiculously tiny package. I am youth and elasticity in a box. I can decide or not if I want to bleed, by the simple act of renewing my pills every month. I am ready to be used, consumed, taken, and everyone around me senses that. The utopia of my body and this relationship with A does not last very long: I soon realize that the pill cuts off my appetite, my desire, and my libido. I suddenly become this desirable object which can’t be consumed.

A and I seemed to exist in perfect disharmony, a body hooked on natural testosterone, another one sedated on artificial estrogens. I hate how cliche it sounds and how grounded it feels. I now see our dysfunctionality clearer. Being on Diane35 is similar to getting a free ticket to the buffet when you just lost your taste or appetite. A luxurious hotel without a swimming pool. A reminder that it is impossible to win at everything in life.

As for many other conditions, an interesting dilemma operates between the researchers in the healthcare field and the ones who experience the condition. Is it not the perfect timing to either, create a technology that would completely free us from our biological conditioning and its complications, or on the contrary enable us to connect to the core issue and fundamentals of our bodies and their functioning by rejecting technology? Although these two separate movements do have a correlated goal (to emancipate) they seem to look into two separated notions of technology. The first one belongs within, is more ancestral, holistic, and so-called “natural”, while the other one bets on technological assets and medical advancements to free us from the condition. While these two battles and research fields are worth looking into, it is necessary to emphasize a third question that needs to be examined and criticized: the effect that the environment and its design around us have on us.

In the article of the Atlantic, Why to Menstruate If You Don't Have To?, journalist Marion Renault illustrates the dilemma which operates in a society where many menstruating bodies would rather not experience the bleed of their biological body. While the reasons for such choices are sometimes linked to intense or unbearable pain, body dysphoria, or the lack of access to product/resources for menstruation, it is also emphasized that the underlying need and desire is to be optimal and functioning, or rather, compete better with other individuals which are not menstruating. “I want them to be competitive against those who don’t have uteruses,” Yen said. “Teenage years are so turbulent and horrific as is. I don’t want them to suffer unnecessarily—and I can alleviate this for my child.” This thought exists or has probably existed in many of our minds. It is a valid and understandable idea, given the conditions in which our bodies evolve. A society where the conditions related to our reproductive systems are little or poorly studied and where paid leaves due to pain or disability are extremely rare. Not to menstruate, and therefore to not have these conditions, is the newest efficiency dream. It is an idyll because, in this space, our body would not be limited by its biological condition and is not judged for it. A world where we could be functional, optimal and where our body would not be an obstacle to our activities and ambitions. But who sold us this dream? Why should we be optimal, and for whom?

In these artificial attempts to cure and hide, nothing more is being investigated. Coming back to the testimony of Lara Briden in the article Fake periods, side effects, and other things you need to know about the pill, the naturopath unpacks how “Pill bleeds are pharmaceutically induced bleeds … to reassure you that your body is doing something natural,” says Briden. “Many doctors continue to prescribe birth control to ‘normalize periods’ and ‘regulate hormones’, as though the pill’s steroids are somehow equal to, or better than, your own hormones. The fact is, nothing could be further than the truth. Pill steroids are not better than your hormones. They’re not even real hormones.” So, is that it? Will we resolve these conditions and treatments by simply eradicating and replacing natural hormones? Is that all we know? When looking at these artificial technologies of emancipation and transformation, we observe how they simulate the real, the biological, as to convince the “naturality” of their essence. As if our distinction with “nature” and the choices of some individuals to alter their biology wasn’t accepted yet. But it’s already there.

In regards to the second-most administered treatment offered to PMDD sufferers, SSRIs, the positive results of these medications seem to underline the psychological and mental consequences of the condition. While the body seems to correctly react to the presence of estrogen, the main hormone-induced within the first two weeks of each month, progesterone, arriving right after ovulation, seems to be the culprit of the sudden change in mood, embodiment, and perception.

Memes posted by @pmddmemes on Instagram.

Memes posted by @pmddmemes on Instagram.

While the studies of PMDD and its impact on mental and social life were rendered public forty years ago, it does appear that the medical field still has not targeted the exact cause of the sensitivity of what aggravates it. As a result, to this day, SSRIs are the main and only option offered to patients and it should be emphasized that it has shown great results. Still, as for PMS, PMDD is the result of a change that operates hormonally and chemically, therefore its experience and perception are also highly emphasized by the environment in which one finds themselves. If it is indeed hard for an individual to sense their body and mind changing so drastically within such a short period of time, this experience might as well be aggravated by the social pressure which women and menstruating bodies have suffered from for centuries. If SSRIs can help one’s mental capacities and soften their experience, it does demonstrate that the mental burden of those conditions is consequent. If those treatments can ease one’s experience of their body, we should not forget to question what the changes are which need to happen within society for those bodies not to feel sick and oppressed in the first place.

In her book, Women and Madness, Ussher expands her question to a broader range of conditions attributed to female and menstruating bodies: ‘I thus turn my gaze onto three other manifestations of madness ascribed to significant proportions of the female population: borderline personality disorder (BPD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). While my arguments can be generalized to other `female maladies' (such as anorexia or anxiety disorders), these three psychiatric disorders are ideal examples of the pathologization of women's reasonable response to restricted and repressive lives’. I insist throughout this text on the necessity to understand the social component of these issues because a greater design of technology and cures should not only hide or disguise the external reality of the patient but also aim to change and redefine the context in which one exists.

Although it is also emphasized that PMDD can be inherited, studies demonstrate the correlation of discrimination, poverty, pressures to assimilate, etc with the appearance of PMDD or its aggravation. It would be tempting, although hypocritical, not to see a direct link between these conditions and the standards of society in the era of capitalism, in between society’s mechanism, patriarchy, and psychiatry. While PMS and PMDD are now universally known and understood as limiting and hurtful conditions, their existence as metaphors has not stopped existing. In their everyday life, menstruating bodies might still try their best to perform and hide their physical or psychological pain, as a way to counteract the cliche and stigmas which accompany women and anger. Those hide their day-to-day experience as a way not to be discriminated against. Not to be judged. While many fights for these conditions’ visibility and the importance of its study field, it is still a vigorous battle to claim the recognition of the incapacity to perform and live optimally in society.

In 2022, almost twenty years ago, Joan C Chrisler and Paula Caplan published The strange case of Dr. Jekyll and Ms. Hyde: How PMS became a cultural phenomenon and a psychiatric disorder. In this paper, they both investigate how and if social context influenced PMS, and what were the solutions given to those who were highly suffering from the condition. As a result of their findings, they conclude:

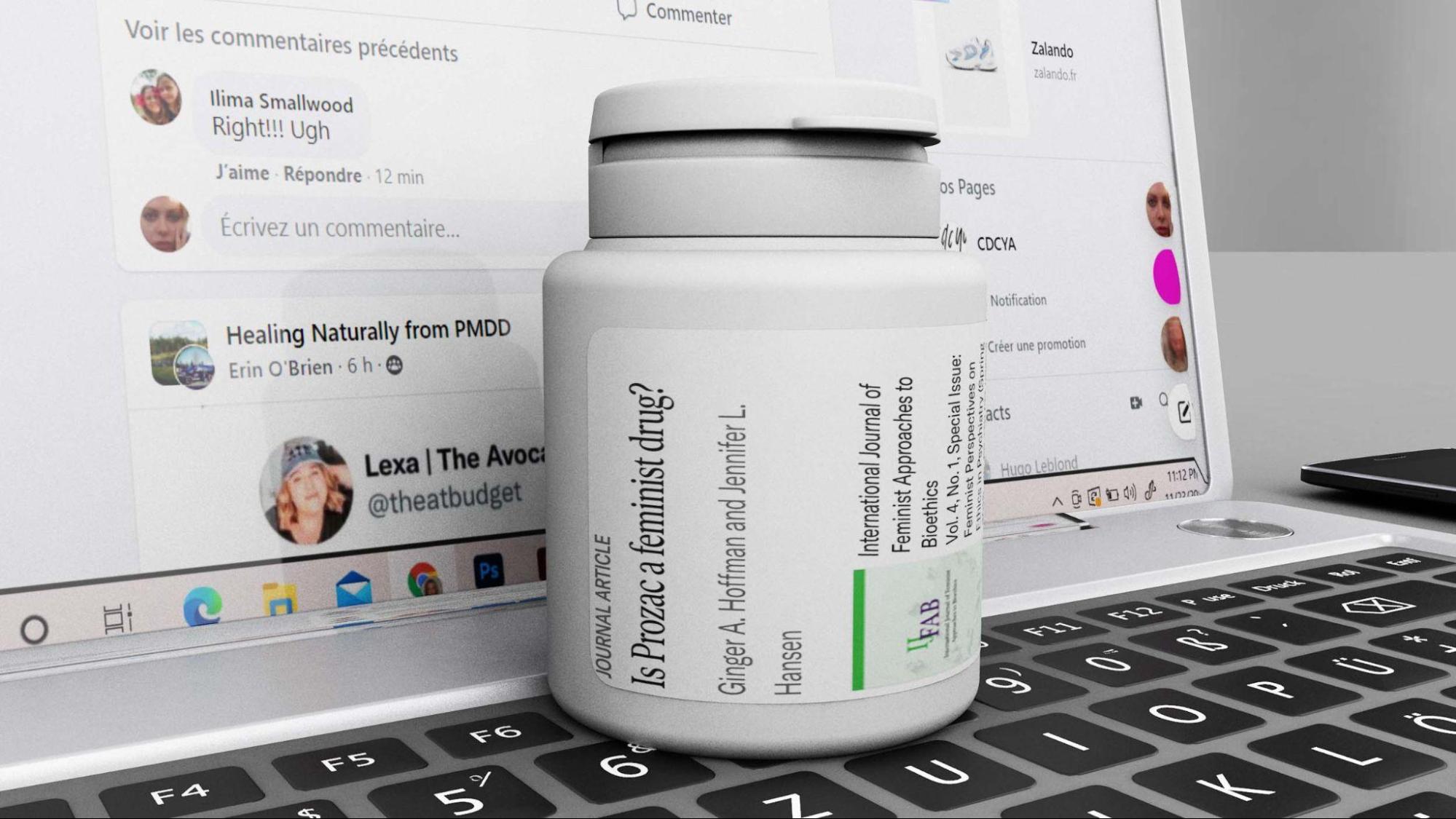

“It is certainly easier to take medication to restore serenity or create emotional detachment (an often reported effect of Prozac/Sarafem) than it is to take steps to make changes in one’s life circumstances, and women are getting the message from advertising and other forms of media that taking medication is what they should do. And psychotherapists may find it easier to help a woman try to change herself in order to fit the feminine ideal; than to figure out how to help her resist the social and cultural pressure to be an ideal woman. Taking medication may provide apparent serenity to individual women, but it does nothing to alleviate the oppressive conditions that contributed to the stress and tension that caused them to report severe PMS. PMS is a form of social control and victim blame that masquerades as value-free.”

Still, here we are, twenty years later, and it does not seem that these considerations have shaped or changed much in the generic medical field. Thankfully, throughout the years, an army of enraged and disappointed bodies gathered to discuss and collect information and experiences which could not be found or mentioned in the earlier times.

Femtech, in Between Holistic and Transhuman Perspectives

A meme posted by @pmddmemes on Instagram.

A meme posted by @pmddmemes on Instagram.

Day 29 - Still a week to go

In moments like these, I feel the urgent need to alter my body or alter my perception. My detachment from people and from physicality has been rather intense these past days. Humans feel strange to me. I’d like to smoke a joint, although I never craved weed. I bought truffles to micro-dose but the prescribed amount isn’t strong enough. I don’t feel anything. When thoughts about past events and urges pop up in my mind, these tiny balls of thoughts either explode to become turmoil and anxiety, or they simply disappear in the overall fog that floats in my head. I am numb.

The perspective of the relief feels quite far and aggravates its urgency. A part of me tries to see despair as fertile ground for experimentation, for change. But how dangerous is that?

It has become nearly impossible for me to write these days. Now, with more theory backed up in my brain, I can’t help but always judge the social construct of these experiences. I am numb.

The feeling I initially wanted to start working with, anger, feels often too long gone. Anger is the energy of beginners, amateurs. It’s the fuel of the ones who want to throw out. And I just don’t know where the battlefield is anymore. Perhaps I can’t write next to anger at the moment. But if not this, then what? It’s too easy for me to call out on this condition and blame it for the state of my mind. It could be a thousand other things adding to my flow of hormones. It could be that normativity also includes numbness. Where’s the line that one draws to call themselves sick?

Why am I not choosing to feel something? Why am I not choosing drugs? Not choosing the pill, not choosing the SRRI’s? Who am I trying to be a fierce warrior for?

Rendered image, Screenshot of the Jstor Library, Article “Is Prozac a feminist drug?”

Rendered image, Screenshot of the Jstor Library, Article “Is Prozac a feminist drug?”

The isolation generated by the knowledge gaps led those who suffer from the condition to find alternative ways to connect through the internet. YouTube, Tik Tok, and Reddit became the site of experiences and testimonials that those bodies would refer to. On these platforms, one can find moving testimonies, cries for help, and success stories of patients who have found their ideal combination to alleviate their symptoms. There, different paths seem to appear, in between the ones referring to holistic fixes and natural flows, and the others, aiming for a neo-human or trans perspective of emancipation and liberation. While these ideologies share similar ideals, they seem to differ on some notions; some aspire to slow down technological processes and their artificial changes, meanwhile, others support the futuristic ideal of biological liberation through science and medicine. Simultaneously, they both question more fundamentally the standards and designs of society that lead to these conditions and treatments.

While these internet groups and communities allowed patients to collect and gather information, share their knowledge and support each other mentally, awareness and actions, something else emerged. From these online gatherings and testimonies in the age of the internet and fast-online-shipping, a new and exponential market appeared - a market much bigger than the PMDD or PCOS market alone. A market whose mission it is to change society, science, the condition of women and to vary the treatments and their accessibility: the world of FemTec.

As we started to face the sudden deterministic realization of our bodies and their conditioning, researchers and tech experts started to assemble, aiming to develop new tools and concepts which would help our bodies and their technologies in everyday life. This new industry appears to be born from a new generation of individuals, an army of strong and ambitious warriors determined to offer wellness and a sense of conformity to women and menstruating bodies. Instead of separating the two previous names ideologies - returning to nature, or emancipating from it - Femtech aspires to exist in between. It aspires to become an alliance of ancestral knowledge and forms of rituals mixed up with digital devices and high-tech tools to enhance our experience and knowledge. Femtech is a thermal ring you’ll put in your vagina to track your temperature. Femtech is a menstrual app that predicts the worst moment of your cycle to make a business deal – girlboss at its finest. Femtech is a DIY kit to try out your fertility and its expiration date. Femtech is when your phone became your very personal gynecologist. Fluids are the issue, digital is the recipe. It is the world that perhaps Donna Haraway dreamt of mixed with nuances of Silicon Valley. FemTech is what technology for menstruating bodies looks like in the 21st century. Within this new ideology, more than often directed and designed by individuals who are other-than-man, it is an interesting moment to reflect on these technologies, their promises, and the obstacles one might encounter when trying to design new technology and a new philosophy for inclusion and care.

Images extracted from the article 'Femtech startups on the rise as investors scent profits in women's health', written by Gene Marks in The Guardian. The Elvie pelvic floor trainer is just one of a number of products from ‘femtech’ startups which have raised almost $50m in recent months.

Images extracted from the article 'Femtech startups on the rise as investors scent profits in women's health', written by Gene Marks in The Guardian. The Elvie pelvic floor trainer is just one of a number of products from ‘femtech’ startups which have raised almost $50m in recent months.

As mentioned earlier, we should not only focus on fixes for our bodies in society and ways to optimize pain or time, but rather think of objects and interfaces which offer care and understanding of our conditioning. The world of Femtech gives a chance for health and care to be designed and understood by a more diverse body of thinkers, designers, and engineers. It could become a revolution if we make sure it does not take the path of an optimization that takes men as the norm and gravitates towards efficiency or productivity. Even more than finding and designing cures, Femtech also has the main challenge to help our bodies fight society’s standards defined by men. This revolution holds a huge potential, one that has been banned, or hidden before: the possibility to target not only the symptoms but also the research, the gender gaps, as well as society’s standards, so far deeply imprinted in patriarchy and capitalism. Within this new field, many questions arise. What can science and technology do to our bodies? Through which aim? For who’s interest? Should we even try to understand these phenomena? Or shall we, as Preciado suggested, live in a world of “molecular excitation”?

While this research field grows and while waiting for more discoveries and fixes to appear, self-diagnosis and medication seem to be one of the ways that patients learn to deal with the condition of PMDD. At this stage, the internet sometimes feels like a safer space to talk and investigate cures. While I wait for changes to appear, and dream of a speculative database where our bodies and conditions could be studied and rendered real, our society keeps on evolving at a fast pace, designed by patriarchy with endless feelings of inadequacy as a result. This battlefield isn’t located at one spot only, it is multiple and intertwined. It is a call for care, for a change in health systems, it is a reminder to not always judge our bodily responses to the world, but also to question the world itself. On the good days, in the first two weeks, I am optimistic and fearless of the obstacles coming in the way of this revolution. On the last two, it becomes harder to stay positive, but at least anger and inadequacy drive me to write. Until the next cycle.

Day 3 - The Dream Girl

Still not at my cutest because my hair is still kind of greasy from the hormones. I always love to shower around the 7th day. I am finally clean and renewed. In the evening, I grab my phone to log in to Field. I don’t know what I am looking for but I NEED attention. I have a partner and great friends but I DEMAND care. There is something in the way I carry myself and walk around the world. My stomach is now flat, my cravings are gone.

I am the dream girl. I feel hot and smart. I desire and I am desired, I stare back because I am a young flesh, young blood, and because it feels so rare, so intense to feel adequate. There is something in the smell of others, in their moves, I could suddenly hug the entire planet, perhaps even make out with it. I wish I could be that girl all of the time, could live on estrogens and serotonin, never get old and always want to fuck. Twenty-four years old, in my luteal phase: I am optimal, and it will never again get better than this. I wake up in the morning acknowledging the time that has already passed and won’t come back, I look at what I already possess. It’s not much, but they all say that at least I have time, I have youth. Youth is not much when understood in the frame of fertility. I have been ovulating for over ten years already and still did not procreate. Something in my mind tells me that I have approximately ten years left. Ten years left, as they say, to find the perfect partner, to assure my back, to carefully think of and act upon, because it is youth and I because I am a woman.

The memory of the fogginess from the follicular phase is already long gone, forgotten, forgiven. I can take the world back, chase whatever I intended to do, but I have to remember: my time is limited. Soon enough, something bigger, stronger, wiser than me will limit my thinking and actions. It is because the time is so short that I choose not to think of the evil anymore. I would rather focus on what functions, look at the bleach of my hair, the hydration of my peachy skin, happily notice the lubrication of my genitals, all of this while I still can.

I have no hate, no. I feel no repression, I go out like a trophy, I am above what is dictated because I am exactly what I was intended to become. I will happily smile at strangers and perhaps fantasize for a second, patriarchy feels like a distant battle which I won because I am optimal. I could choose to love or hate, ride or die, date or break but still, time is running and I should focus on what needs to be achieved, succeed while I still can.

You can follow the ongoing research on https://becomingtheproduct.substack.com/

Biography

Morgane Billuart is a writer and a visual artist. She graduated from the Gerrit Rietveld Academie and studied at the Cooper Union in New York. Currently, she is a researcher at the Institute of Network Cultures in Amsterdam. In the era of digital practices, DIY-internet beliefs, self-help seminars, untouchable or unlived experiences, her practice aims to display diverse forms of faith or beliefs, and how they are generated nowadays. Often, she confronts these themes and interests with her gender and existence as a woman in the spaces she investigates and questions how the forces and fluctuations of female bodies can help us rethink and criticize the technocratic and digital spheres surrounding us.

Books

Jackson, G. Pain and Prejudice: How the Medical System Ignores Women―And What We Can Do About It. Greystone Books, 2021

Paul Preciado, Testo Junkie, Editions Points, 2021

Roxanne Gay, Not that Bad, Dispatches from Rape Culture, Roxanne Gay, 2018

Jane M. Usher, Women and Madness, Myth and Experience, Routledge Books, 2011

Enright, L. Vagina: A Re-Education (Main ed.). Atlantic Books, 2021

Vitti, A. WomanCode: Perfect Your Cycle, Amplify Your Fertility, Supercharge Your Sex Drive, and Become a Power Source (Reprint ed.). HarperOne, 2014

Wajcman, J. TechnoFeminism, Wiley, 1993

Gray, M. The Optimized Woman, O’ Books, 2009

Articles

Zietal, Bianca, "Thesis: The Genesis of Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS)". Embryo Project Encyclopedia, 2021. ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/13216

Chrisler JC, Caplan P. “The strange case of Dr. Jekyll and Ms. Hyde: how PMS became a cultural phenomenon and a psychiatric disorder”. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2002;13:274-306. PMID: 12836734.

Ah-King M, Barron AB, Herberstein ME. “Genital Evolution: Why Are Females Still Understudied?”. PLOS Biology, 2011, 12(5): e1001851. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001851

Hoffman, Ginger A., and Jennifer L. Hansen. “Is Prozac a Feminist Drug?” International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics, vol. 4, no. 1, University of Toronto Press, 2011, pp. 89–120, https://doi.org/10.2979/intjfemappbio.4.1.89.

Pilver, Corey E et al. “Exposure to American culture is associated with premenstrual dysphoric disorder among ethnic minority women.” Journal of affective disorders vol. 130,1-2 (2011): 334-41. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.013 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.013

Magazine articles

Lucey, K. (2019, October 7). PMDD is the condition that means your period can make you suicidal. Metro. https://metro.co.uk/2019/10/05/pmdd-condition-means-period-can-make-suicidal-10865751/

Metcalf, A. (2021, October 8). This Disorder Affects Millions Of Women, And No One Is Talking About It. Why? The Candidly. https://www.thecandidly.com/2019/pmdd-affect-millions-of-women-so-why-arent-we-talking-about-it

Scott, J. (2018, August 8). Fake periods, side effects, and other things you need to know about the pill. Vogue Australia. https://www.vogue.com.au/beauty/wellbeing/fake-periods-side-effects-and-other-things-you-need-to-know-about-the-pill/news-story/006e70f2afb4fd78c4616bcd1417add2

Renault, M. (2020, July 23). Why Menstruate If You Don't Have To? The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2020/07/why-menstruate-if-you-dont-have/614350/

Sex hormone-sensitive gene complex linked to premenstrual mood. (2017, January 3). National Institutes of Health (NIH). https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/sex-hormone-sensitive-gene-complex-linked-premenstrual-mood-disorder