Figure 1: Screenshot from Clue App and no coping mechanism.

Figure 1: Screenshot from Clue App and no coping mechanism.

One more menstrual cycle that lasts more than forty days. The bitch isn’t in a hurry, and my Clue app gently reminds me of it. Some would freak out about it, but with experiences I’ve learned that I shall not fear pregnancy but rather question the difficulty my body has to develop and produce the hormones that lead me to bleed. Before I downloaded any of these apps, the only technologies I used were my own senses and the internet. Not one other institution could justify my flows and their occasional absence within this body. Self-study and self-acceptance were the only ways to carry the “anormal” and the “nonfunctional” when dealing with unknown or poorly understood phenomena.

As for many other individuals who might experience unconventional fluctuations or conditions (such as PMDD, PCOS and Endometriosis), I could not believe how little support and understanding there was in institutionalized medical spheres. This enormous gap in knowledge and public information felt absurd and unjustified. In this ocean of bodies suffering from unrecognized or poorly studied conditions, I eventually realized that I wasn’t the only one notifying this lack. Various researchers, activists, writers, and artists are making similar statements.

The question is, to say the least, rather simple: how can it be possible that in the 21st century, with all the technology and networks available to us, we still fail to observe patterns to make better sense of these conditions? How can it be possible that all the resources and experiences shared on the internet are not sufficient proof for the medical field to reconsider its dogmas and biases?

Online, people are exchanging knowledge and experiences about their diseases, their cures and their failures. There, myself included, we all seem to get lost in a sea of information, forums and private groups. For the sake of healing, it seems as if there is no limit to our openness and flexibility. Facebook groups and YouTube videos are filled with crispy details and reviews about the most awkward products and experiments. Do you suffer from rosacea? Perhaps this homemade cream with soybeans could help. Irregular cycles? Surely you should limit your milk intake as these hormones mess with yours. Chronic bladder pain? Try steaming your body with these herbs, but be careful if you have an IUD.

We all seem to be swimming in an overflow of possibilities, cures, and homemade solutions to our bodies’ problems and apparently regret that there exists no platform to gather those precious journeys. Of course, we know that we are not alone to dream about such a place. We are all very much aware of the fact that the GAFA’s have started digging into this project as well. As health data became the newest golden nuggets, pharmaceutic industries and lobbies have jumped into the race, hoping to lead the way.

When I feel at my worst, I would gladly give up all my privacy and intimacy away just to give science a chance. To give technology a try and better target the roots of these issues. When I feel like I am losing it, and when I get the feeling my peers are falling too, I sense a hidden common secret agreement between us - one of sharing and relaying on information as much as we can, in the hopes of us giving away something that contributes to a greater chance of change and a better sense of understanding. Sharing our feelings and symptoms on the internet enabled us to connect, exchange, grow, and rely on an ethereal structure that maintained and held us together.

Still, these visions of privacy and safety sacrifices have to be put in a context where technologies and medical systems have often demonstrated to not want the best for female and menstruating bodies. The most concrete example in 2022 is of course the overturn of Roe v. Wade by the U.S. Supreme Court, leading millions of individuals incapable to rely on their rights and the disposable of their bodies. As this new law was enforced, it increased the number of users of platforms and apps related to health and well-being, which in turn changed their related practices. These free and accessible tools where one can share knowledge about their body had become suspicious, dangerous. In some parts of this world, sharing information with the digital world had taken a totally different turn, transforming a gesture of care and connection into a fear of being observed, surveilled, or even punished.

When it came to the advancement of a better understanding of marginalized bodies and disregarded conditions, one could easily think of a hypothetical easy fix; one of collecting information and producing a piece of new knowledge. Surely, the problem is structural, but if only we were able to look into the causes and not the consequences, able to develop better tools facilitating the understanding of how hormones fluctuate and change our bodies. I was, and still am to a certain extent, blinded when I ask how come a platform displaying cures and information about these conditions does not exist yet. I, too, was naive enough to write proposals where I sought to investigate “the technologies of menstruating and female bodies''. In the beginning, it did not appear that complicated. The communities existed and they were willing to share their insights and experiences. All there was left to do, supposedly, was to collect it and move from there, hopefully rendering a better understanding.

If we can send men to the moon, I thought, something could be done for our health and its representation in society. Brilliant are the ignorant. Soon enough, I realized the networks of complexities entangled in this agenda. But every dream has to start with some suspension of beliefs, and I’m happy I tried.

Collecting and Archiving: A small History of the Patient Equation

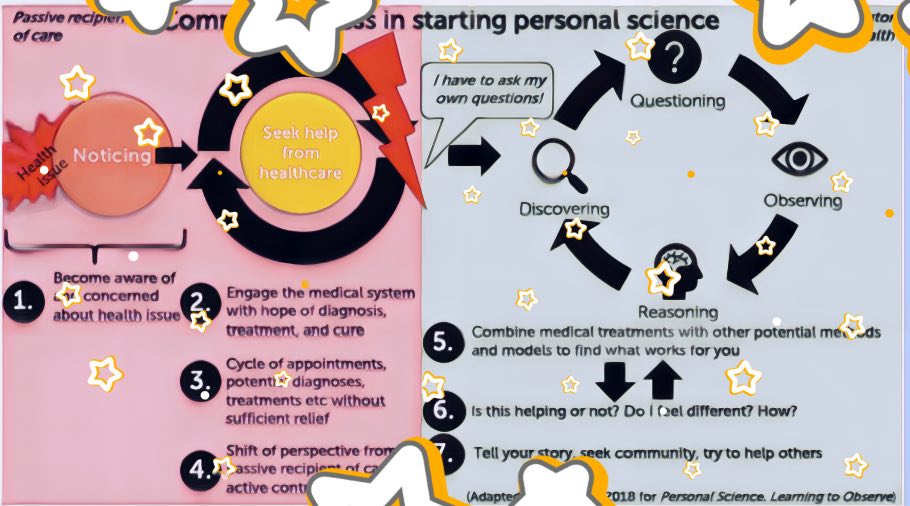

Figure 2: Screenshot from StepsApp

Figure 2: Screenshot from StepsApp

The act of gathering information and the rituals of healing and exchanging knowledge about each other’s bodies existed long before the internet’s birth. Secret meetings and alternative ways of healing were part of the many strategies that minorities, marginalized, disabled bodies, and women at large used in order to take care of their bodies when other systems were failing them. Through journaling, quantifying, and observing their own body and their reactions to substances, these bodies tried to educate themselves and others on the matters that science could not touch or see.

These past years, and on a more global scale, the movement of the quantified self re-emerged to underline the need for self-awareness towards our bodies and their relation to everyday habits. Calibrated as a machine, the quantified-self movement invites individuals to collect and trace their bodies’ behavior in order to better understand its functioning. With a minimalist design echoing the aesthetic of the care industry, the Quantified Self platform presents its users with what appears to be common sense about body awareness and self-knowledge:

“The Quantified Self is an international community of users and makers of self-tracking tools who share an interest in “self-knowledge through numbers.” If you are tracking for any reason — to answer a health question, achieve a goal, explore an idea, or simply because you are curious — you can find help and support here.”

Designed under the name of “personal science”, the quantified self movement seeks to awaken people to their own agency in terms of health, care, and personal development. More than a simple journaling experience, this community also investigates fundamental questions that feed multiple debates within the field of digital health. As a cult would, they implement their kit, write books about the topics, and live and eat through observations and reactions. Simultaneously, they also reflect on the improvement and access to their own data, and the design of wearables, but also (sometimes) raise questions about privacy and individual agency. At the core of their practice, this movement aims to merge quantitative and qualitative observation, a strategy long ago defeated in generic medicine practices.

Figure 3: Image from the website Brief History of the Quantified Self Movement

Figure 3: Image from the website Brief History of the Quantified Self Movement

Historically, tracking your own health and the many different ways to heal was a normative practice before it became a niche ideology on the internet. In the text Measurement, self-tracking and the history of science: An introduction, researcher Fenneke Sysling helps us contextualize how self-tracking and analysis are rooted in the narratives of our world, and more specifically in the history of medicine. From ancient methods of ‘monitoring [our] body and its weight changes through food ingestion and discharges’ to surveilling your diet and the smallest details of our lives, the quantified-self movement already existed and was already embedded in our everyday life. After all, it is common practice to try to limit our exposure to pain, disease, and discomfort. Additionally, the researcher adds how this not-so-new ideology helped spread the ideology of individual “intelligence”, while reinforcing the ‘increasing (self-) surveillance that our society requires and that this technology has pushed.’

Your personal written diary would never disclose what eating pumpkin seeds did to your cycle, or relate what sleeping five hours a week did to your libido. Your apps and other digital platforms, on the contrary, could be interconnected with many different parties that would pay a fair price to understand the correlation between the two, and along the way develop a product meant to fix it all. Nowadays, the quantified self aspires not only to collect and observe the body but also to participate in the technological revolution of data collections and patient equations. Books about such topics have a rather utopist tone. One resembles the failed utopia of Welcome to Gattaca; a world where optimality has become a quantifiable formula that only a specific lifestyle can provide, and where individuals failing to meet these habits fall into a lower-class category. These books and landscapes depict a world where health is embedded in science, and where nothing can escape the sight of data collection and quantified prevention.

In The Patient Equation, Glen de Vries underlines the endless change that one could operate if one could crack human health and figure out the best possible equation:

“(...) imagine a world where as soon as something useful could be detected, be it a data point we can track with conventional medical measurements or a misbehaving molecule or behavioral pattern that we may not even fully appreciate today. We would be prompted to take action, use a medical device or drug, or change some aspect of how we live.”

Books or ethical readings similar to The Patient Equation appear as a reference object of study to better understand the ideology beyond such enterprises. Often written by doctors or scientists, these phantasms of a fully apprehensive, calculable, and foreseeable future find their ground in a debilitating observation of contemporary health care and its costs. While observing the decay of a medical system that fails to sustain itself, these researchers ask: what if we could cure and prevent people’s diseases? What if our healthcare system was trained enough so people would not have to guess the root of their discomfort? An ideological revolution that more and more professionals in the healthcare system seem to join, as they observe the rotting structures of the medical spheres and the limitation of its treatments.

In Healthcare Is Killing Us: The Power of Disruptive Innovation to Create a System That Cares More, Aaron Fausz emphasizes the need to rethink a system where consumers are respected and in control, and ‘where communities fare focused on prevention and health instead of just on sick care and where pricing is no longer hidden’. But as the medical and care industry slowly dies of debts and flourishes from more ongoing privatization, it seems that the required changes have very little chances to be put into an application without a foreseeable notion of profit within its formula. More than a new conception of health where listening and prevention are key factors, The Patient Equation underlines the infinite possibilities of quantifiable systems where one could realize that the drugs offered to us are, perhaps, not the most efficient cures. The author writes: “so many things are so much better than drugs, things we are not even running studies on”, leaving the reader to imagine a world where medicine would have a totally new meaning, one that exists outside of lobbies and pharmaceutical industries, one that enables individuals to care and sometimes cure themselves without the need of a system-reliability.

The challenges in the medical sphere and hospital structures are a more complex topic than the Quantified Self ideology alone. At its roots, this phenomenon simply invites each individual to train themselves into getting to know their body better and eventually have a better grasp on their health. By analyzing every aspect of your life (which authors you are reading, how many steps you are taking a day), one may get to crack the code of their own well-being and live a more authentic, transparent, and fulfilling life. Unfortunately, one cannot think about self-tracking and performance optimization outside of a neo-liberal system where profits and exploitation sit at the corner road of our paths. Whether it be to control, survey, or turn into a formula of product-based consumption, the economy of information and extraction wants you to heal, but not in the way you decide to.

In The Quantified Self and the Evolution of Neoliberal Self-Government: An Exploratory Qualitative Study, Thomas J. Catlaw and Billie Sandberg question the ambivalent aspect of neoliberalism in these new self-aware ideologies. As explained in their research, social groups often reunite and detach from authority and expertise following the failures of these structures to fulfill their need. (Un)fortunately, one notices very rapidly that these exchanges of knowledge and experiences are still hosted and shared on neo-liberal platforms (social media, apps, ect.). As a result, these social groups are moving from a structure that failed to support them to a structure that does not always want the best for their safety and privacy. Whether or not these platforms will redistribute back the user's information to the institutional platforms often remains a mystery.

Data collection for female’s health: Self-Tracking and The promise of Digital Health

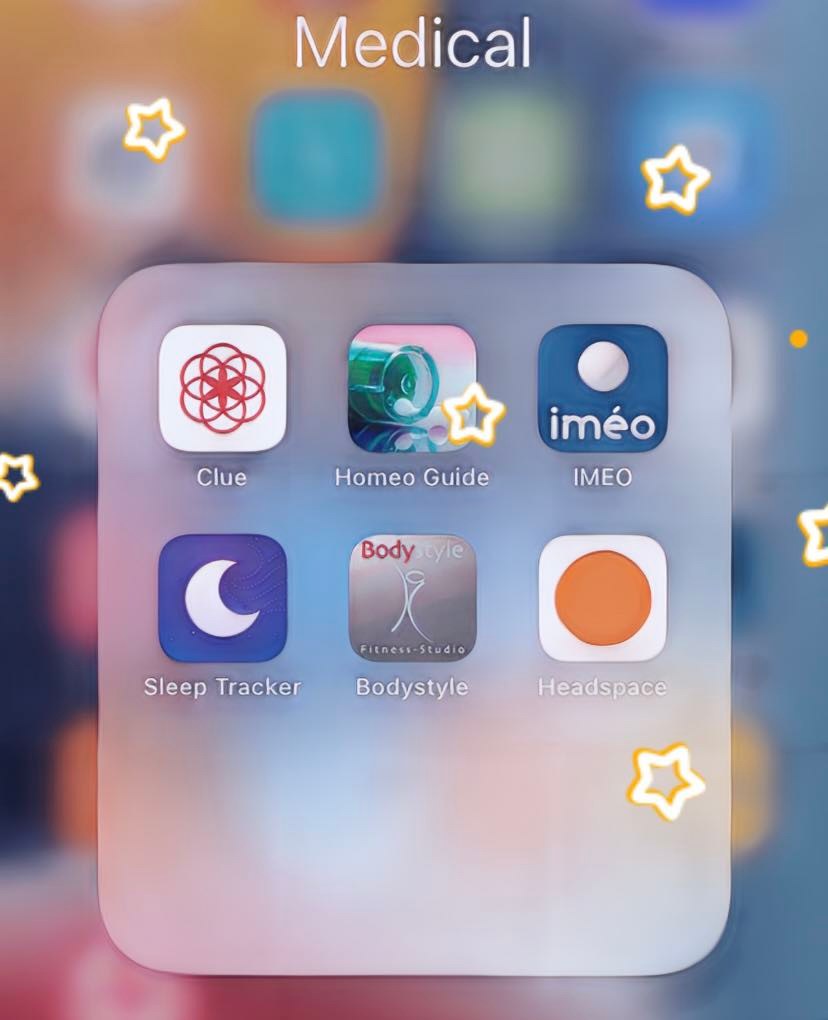

Figure 4: Screenshots from my medical category on iPhone.

Figure 4: Screenshots from my medical category on iPhone.

‘Every woman is a self-tracker.’

I wish I remembered where I’ve read this sentence, but I don’t.

This quote stayed with me intimately throughout this research, convincing me that the advancement in health and care would be rooted in an approach highly influenced by females' and women’s experiences in the medical field. In 2020, I had the chance to travel to Coimbra to attend a course on robotics within an engineering company that had gently accepted to take a non-initiated student (and artist, additionally) to attend their class. From the many different things I traveled with to this country, I took along the beginning of what I thought was a chronic cystitis in my luggage. This trip to Portugal, as one would imagine, was a journey full of challenges with different colors and flavors. Lost in a sea of numbers, math, and attempts to practice logic (which I had not done for quite some time), came additionally a slight but acute pain in my lower stomach.

During the various medical interventions and in the mixture of the multiple prescriptions, I quickly realized that nobody (even myself) knew what was going on, and even less how to treat the pain. Anti-bacterial, antibiotics, probiotics, blood tests, urine tests… The list of treatments could have been infinite, but there was no trace of virus or bacteria to be found. After a few months of trial and error, of lonely and painful experimentation, taking risks with drugs that were not recommended but that I had read about somewhere online, I resigned myself to going home back to France and seeking help there.

It wasn't the first time and will certainly not be the last that I’ll have to perform this sort of experimentation. Throughout the lived experiences of female bodies, it is a rather intuitive and organic move to think of self-medication and lonely experimentations. A strategy that was no longer strange, considering the number of diseases that are misunderstood, unknown, under-researched, or completely ignored. In Sexism Kills: Medical Misogyny and Ignorance of Female Bodies, Anastasia Lacina draws an extensive history of women, pain, and hysteria, underlying how numerous were the historical moments that forged medical misogyny. Sadly, she also emphasizes how contemporary this matter remains:

“Medical misogyny has existed throughout all of human history, and it has harmed and killed millions, if not billions, of women. Does it still exist today? Of course, the answer is yes. (...) women are aware of this fact: of 2,400 surveyed female chronic pain patients, 90% of them reported feeling discriminated against because of their gender by their doctors.”

These haunting numbers and observations in regard to the mistreatment and misdiagnosis of these bodies are real and even worse for black, non-binary, and trans individuals which, additionally to their pain, suffer from misunderstandings and racist apprehensions around their bodies. The highly performing and functioning women ruling and living through the many different tasks they deal with elegantly and silently every day seem to confuse a lot of individuals into thinking that women’s status quo and treatment are now equal and that our chances to exist and live remain the same. An observation blinded to the point I mentioned earlier, which is essential to every woman's, minorities and sick people’s life: affordable care treatment for conditions that can’t be quantified and diagnosed is scarce, if not non-existent. If some individuals seem to still thrive and apparently remain optimal, it is only because many of them don’t have any other options than to swallow their pain in silence and keep on thriving efficiently.

Dr. Gabriel Maté, a renowned addiction expert, extends on these phenomenas by calling for a revision of our criteria regarding the notions of care and healing in an oppressive environment. In his new book, The Myth of Normal, he dissects why chronic illness and general ill-health are on the rise. Simultaneously, Dr. Maté digs into the concept of “normal” and the different processes of healing in a toxic society. His research helps us understand how a sick body does not have any chance to heal in a care system that does not really give them a chance to fundamentally take care of themselves psychologically and physically. While works of such intellectuals are needed to better understand the structural and discursive issues within this topic, the personal notions of self-care, self-protection, and holistic treatments should not discourage anyone to ask for the institutional need for attentive care our bodies need. It is with a similar dynamic, one of knowing and healing, that the Femtech movement, and Digital Health as large, emerged in the female’s health debate. This movement's main aim, to uncover more knowledge about our bodies and health through the support of technology and care, seeks to answer the overall crisis in knowledge about minorities and their bodies. An attempt, that, conceptually, echoes as one of the greatest ideas of the 21st century, offering a mirage of possible solutions for a problem that, to this day, has not been resolved. Still, mixing up years of rigid technological understanding and silicon valley’s designs with the fluidity, the ever-changing nature of individuals' experiences is more complex than it appears to be. Interestingly enough, when Femtech and Digital Health seek to collect information and render new forms of knowledge, they seem to encounter very similar obstacles. It is apparently not that easy to expose our daily life experiences and emotional fluctuations into a world of binarity and labels.

In the early stages of this research, I decided to attend a Data Science course in partnership with a health-related company. There, I had the opportunity to meet Rob in 't Zand. After having suffered from a severe injury due to an accident, Rob hung out for months and years on the internet, seeking support and help that he could not find elsewhere. With a background in informatics and business management, he decided to start his very own project: Health Thing, the potential future social media platform for health. While the exercise at heart in the early stage of the start-up development was focusing on the mental health of healthcare workers in the Netherlands, the long-term goal was to connect more people through care and knowledge. Rob kept on saying that the gamification of the Health Thing experience would be the “cherry on top”, but first, we’d have to figure out a modeling formula for a patient and run an analysis on dummy data to better understand the kind of information at hand.

Mental Health’s data collections and Femtech sources of input hold very similar grounds and challenges: they both rely on the user’s will to share information about experiences that are, in essence, hard to qualify. Physical pain, brain fog, an overall sense of confusion, pain, or the awareness of the toxicity of one’s environment… These two fields of research shall seek the use of both quantitative and qualitative data to be able to render a realistic overview and understanding of the user’s experiences. But anyone who’s interested or working in these matters quickly realizes that the human is not a self-evident category. In The Patient Equation, the authors leave the reader with open notes on such an investigation by inviting us to respect the unquantifiable. Still, this respect does not mean the end of research on health and well-being that has now transformed into a gold mine of profit and potential product development. Additionally, social and health agencies have highlighted the female gender as one of the priority groups in policies, programs, and research. As a result, the unquantifiable notion of our everyday experiences does not scare the data science field and the activists behind these dreams, and it is through barometers, scale, and numbers that one decides how the journey felt, how deep the love is for our partners, and how dooming the premenstrual syndrome can be.

Figure 5: Screenshots of sims’ barometer score for happiness and well-being.

The limited understanding of our bodies: on binaries and data feminism

Anyone willing to collect, label, and qualify will benefit from the uses of SQL, Excel and Python. Once collected, the binary information arrives on those platforms, ready to be treated, cleaned, and delegated with care. One’s assumption about data is that it has a golden-like color, that it looks complex, somehow secretive, and perhaps that its worth defines its design. Often, this consists of simply poorly inserted numbers or words from users who could not really be bothered to fill in their information properly. A data scientist's main task on an everyday basis is to formulate hypotheses about the collection at hand, clean those, and formulate visualization somehow answering the initial hypothesis.

While working for Health-Thing, my team and I quickly realized the difficulty of this project while trying to formulate a research question: how is ‘good mental health’ defined? What are the criteria for ‘a good existence’? What kind of barometers could we use to efficiently and accurately assess people's quality of life?

In my daring quest to better understand these phenomena and their limitations, I found myself again surrounded by engineers. This time, no sunshine and natural Portuguese parks were on the horizon, just a lot of Zoom meetings with a fake Rotterdam background. I feared that this experience would be as traumatic as the previous one, but somehow I quickly realized that I was surrounded by team members and mentors who were as confused as I was. The beauty of men’s audacity is that they ignore the complexity of the problem and still, it does not stop them. Throughout our discoveries, we realized not only that it was rather complex to define the criteria of such “good” or “bad” experiences, but also that the use of barometers, scaled from 1 to 10, was often limiting the overall concept of mental health. Not only were the assumptions difficult to formulate, but the data sets themselves were rather confusing. If the users did not see any particular obstacles in the limited answers, the interfaces they were using), left us with a random amount of users connecting multiples times throughout the day to change their barometers, while others users were barely ever letting us know how they were feeling. Through the use of medians and different tricks not to let certain users' presence overtake our analysis, we quickly noticed how difficult the enterprise of collecting online information and rendering those could be.

Although the aim of such a project - quantifying and analyzing mental health to better cure or prevent health problems - sounded like a relatively positive and worth-living-through challenge. The reality of its tasks felt limiting, reductive, and extremely tedious. I now do not wonder anymore why Clue is only giving me the bare minimum information on my cycle and its predictions: attempting to deliver additional analysis would probably cost a lot more and is probably pretty much impossible at the moment. The similarity of female health or mental health challenges in relation to data science is that they both rely on information that is, in essence, hard to grasp and understand. Simultaneously, as for the research led in the quantified self movement, they both rely on the need for both qualitative and quantitative information. Companies, start-ups or institutions minimizing these components will surely fail in understanding these phenomena, and therefore dismiss what needs to be proven. Either with the help of Natural Language Processing, and drawings, or with the ability to choose more “empirical options” on apps and platforms, the attempts to render a more realistic and quantifiable experience of our bodies is on the rise.

Still, the advancements in the creation of knowledge on our bodies through numbers suffer from many complications. In the paper Challenges for Big Data in HealthCare, researchers Kruse CS, Goswamy R, Raval Y, Marawi S. underline the ‘nine themes [that] emerged under the category of challenges’, naming mainly problems regarding data standardization and inaccuracies in data. Additionally, many researchers strongly emphasize how, based on biases and faulty calculations, data replicates systems and powers, reminding us that the use of data collection is one way, but cannot be the only way to provide knowledge and care within our society. This overall reflection on the quantifiable quality of human experience is also investigated from a perspective of gender fluidity and underlines how non-binarity, for example, is extremely difficult to categorize and represent within these systems. In the article Adapting Data Science for Non-Binary Inclusivity, writer Sidney Kung shows how “multiclass classification makes the assumption that each sample is assigned to one and only one label. For example, fruit can be either an apple or a pear, but not both at the same time. Although these multiclass models deal with more than two classifications, the aspect of binary categorization still remains.” This difficulty to bring complexities into models and patient classification show us that there are still many adjustments and changes to proceed in the language and technical possibilities of data science. If we want these tools to be able to give us realistic and ground-breaking insights on the things that we do not know yet, there must be more attention given to the tools used and the selection of individuals that are studied.

It is with a similar observation that researchers and data-scientists Catherine D'Ignazio and Lauren F. Klein came up with the book Data Feminism in 2O2O. Through thorough analysis’ of power structures and requirements for equal and fair treatment of users’ information, Data Feminism imposes itself as a must-read for anyone who is interested in the challenges at hand for this upcoming discipline. As they question systemic power structures defining the results of data visualization and question ways to let go of binary logic, both researchers insist on the embrace of emotion and embodiment throughout the process. Most importantly, they underline how “What Gets Counted Counts” and try to therefore rethink binaries and hierarchies. If we truly want to better understand global phenomena, how can we make sure that the minorities and marginalized bodies we are interested in are actually part of the research and become users? How do we bring, not only gender but also race and social diversity into our research?

For these two researchers, the hypothesis is blunt: if we want to use data and design for a change for the better, we need to look at the most oppressed individuals and how they suffer from these binary and systemic repressions. It is only through looking at their experiences that we can make sure that the people above also get their needs covered.

Let’s go back to the idea of collecting information from social media or Facebook groups. Data analysis and collections need a lot of accuracy and many, many points to be able to dictate a vision of our human experiences. The quantity will surely be there, but what a mess it would be to classify and label all information and each individual. Haunting, to say the least. Also, one should be aware that the knowledge shared online often comes from more Western-like lifestyles or communities and therefore represent a “majority” of experiences shared online, but should not become the referral understanding for these conditions, as it has been proven that medications and treatments do differ and have diverse implications depending on gender and race. When finishing the research on Data Feminism, Catherine D'Ignazio and Lauren F. Klein write a final, still grounded statement: the numbers don’t speak for themselves. Consider context.

For some people, the urgency to seek care and help in a non-institutional manner is imminent. Additionally, they cannot wait for data science to become miraculously inclusive and caring. In her book, The Hologram, Feminist, Peer-to-Peer Health for a Post-Pandemic Future, Cassie Thornton proposes a system that does not rely on hospitals or specialists, but rather on a triangular group of exchange and care. The premise of her practice is rather simple: three people meet on a regular basis to discuss how they feel, reflecting on the physical, mental and social health of a fourth - the 'hologram'. In return, the fourth person also participates in another group where they give care, giving a chance to the system to expand. A peer-to-peer network that uses the internet, sometimes, if the connection is needed. A system that does not rely on the promises of a utopian digital future to be able to heal. Examples such as this one allude to science-fiction scenarios in our ears. We’ve been so well trained to stroll in an individualistic healthcare system. But activism and organization as such make us reflect on the will and energy disposable in each and every one of us to better change and support each other in this quest for care and understanding.

Data and science are one of the many portals to access in this journey, but embodiment, personal experiences, and genuine care should not be missed in this patient equation.

You can follow the ongoing research on @billuartmc or on https://becomingtheproduct.substack.com/

Biography

Morgane Billuart is a writer and a visual artist. She graduated from the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam and studied at the Cooper Union in New York. Currently, she is a researcher at the Institute of Network Cultures in Amsterdam. In the era of digital practices, DIY-internet belief, and self-help seminars, her practice aims to display diverse forms of faith or beliefs, and how they are generated nowadays. Often, she confronts these themes and interests with her gender and existence as a woman in the spaces she investigates and questions how the forces and fluctuations of female bodies can help us rethink and criticize the technocratic and digital spheres surrounding us.