Behind the screen, my computer generates a specific combination of binary digits, so that I’m able to read the intended output spelling the word ‘Introduction’.1Found through Rapid Tables, an online text-to-binary converter: https://www.rapidtables.com/convert/ number/ascii-to-binary.html The first computers that worked in binary solely displayed plain text on a monitor. Perhaps because of the minimal capabilities of data input and information, the user was more aware of its binary blueprint than I am now. Since then, incomprehensible combinations of these same numbers have generated images, text, and video that collectively compose the digital universe that many of us participate in and are familiar with today.

The first computer utilised by the general public was released in the early 1970s. Known operating systems like Ubuntu, or Windows, to the browser itself and the websites that run from it, are all visually designed front-ends, so the average user doesn’t have to trouble themselves with the code that is written, and constantly running, inside the back-end. Similar to the ease in which an animal appears on our plates, in perfectly cut pieces and pre-packaged with no recollection from a possible slaughterhouse, or, more likely in the future, no recollection of the animal itself through lab-grown meats, similar disconnection takes place with the actual hardware of the computer and the waste it produces.

Not only are we disconnected from the intrinsic details of that which is behind the interface, as the (problematic) datasets that are used for, for example, machine learning purposes, so are we in terms of the actual physical impression it leaves on the environment. By using words like “cloud”, as in cloud–computing, it seems that data is stored in a place that is not capitalised, namely air, and from which it might, arguably, seem there’s plenty. However, this oversaturated, increasing, symbolic cloud, is upheld by physical supercomputers, data centres and server farms. “Google has become the world’s largest manufacturer of computers, albeit exclusively for use in the server farms needed to keep this empire alive.”

Zeynep Tufekci starts off her essay We Were Always Human with Plato’s claim that writing robs the words of the soul, as these words are frozen into a fixed medium that is disconnected from the body of the communicator. By doing this, she illustrates that Plato fell for the oft-repeated argument that new technologies trigger a loss of humanity. She argues that this unease stems from technologies that make possible a separation in being human: while we are embodied and symbolic, writing, in this example, isolates the symbolic from our embodied side. “Thereby creating the gap Plato laments: words without bodies”.

The assemblage of data that generates the digital universe, or digital realm, belongs to a technology that disconnects its digital reality, from its very physically located operating body and, likewise, separates the symbolic from our embodied side of being as its user. Within this text, the digital realm implies the universe located behind the screen, which operates from hard drives and web servers and from there, simulates a digital universe where one's imagination becomes more tangible and animated. In the physical realm, one sits behind their computer for two hours, meanwhile, in the digital realm, the symbolic self is not restricted by their embodied aspect, interacting with people and visiting locations that would defy the odds in the material world, all in a matter of seconds. Thus, within the digital realm, our symbolic aspect of being is not necessarily frozen into a fixed medium as Plato critiqued; au contraire, here the symbolic self is very malleable. It is rather the conditions that have changed.

From 2008 to 2011, artist John Rafman created Kool-Aid Man, a tour guide in Second Life, to explore these user-created landscapes. In 2010, Rafman was interviewed by net-based artist, writer and curator Nicolas O’Brien while they wandered through this dynamic virtual landscape together. In a way, the ingredients of a material interaction are present: a body constructed out of pixels, a navigational landscape and vocal communication. The experience of the interaction itself, however, is different to a material interaction, considering both the thorough manipulability of all three qualities and the third-person view from which they see themselves as well as each other. It’s a different universe, therefore it plays by different rules.

Hence, within the digital realm, the leaving behind of the physical body is a fact, but this does not necessarily mean that the embodied capacity of humanity is fully disregarded. Due to digital avatars, our symbolic aspect of being can adopt a representation of an embodiment, albeit built from pixels.

Enlarge

Figures 1 and 1.1: John Rafman/Kool-Aid Man and Nicolas O’Brien having a conversation in Second Life.

Plato’s soul left this earth a long time ago, yet ironically his words, wisdom and writings have been frozen in time, carried for over two thousand years, to be reinterpreted by others and, now, me. The digital realm serves not only the preservation of renowned writing and people, but via social media and blogs everyone can put their words on stage and eternalise them. Next to the conservation of the symbolic aspect of being, the digital realm offers the potentiality of continuation even after the embodied side has passed on: LivesOn is an example of an artificial intelligence project that is working towards a digital twin, so that ‘when your heart stops beating, you’ll keep tweeting’. Whereas Audrey Hepburn reemerged in CGI for a Dove chocolate commercial in 2014.

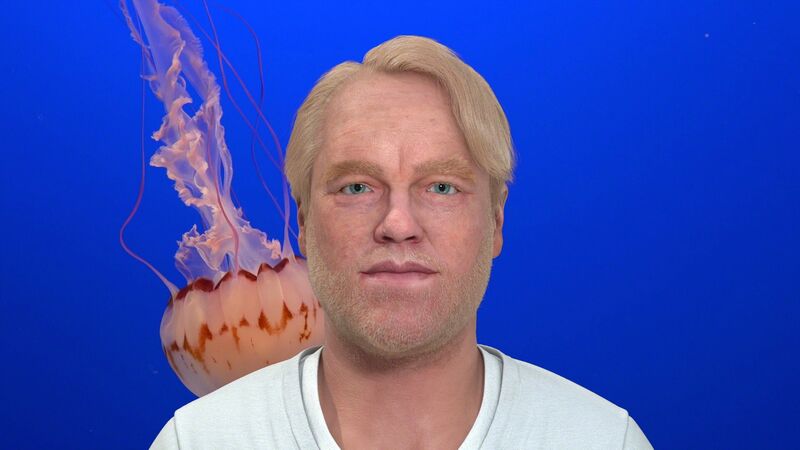

In the same year, actor Philip Seymour Hoffman passed away during the production of the final two movies in The Hunger Games blockbuster. The director disapproved of resurrecting Hoffman through a digital copy to finish the movies. This inspired artist Cecile B. Evans to use a poorly rendered CGI version of Hoffman as narrator for her video installation Hyperlinks or it Didn’t Happen, named PHIL. Here, PHIL does not represent Hoffman, but the “failed” CGI copy that developed into a separate digital entity as he, among other immaterial entities, searches for meaning.

Enlarge

Figure 2: PHIL in Hyperlinks or It Didn’t Happen (2014), Cecile B. Evans

Until now, I have addressed the digital realm in relation to the human being. However, in the case of PHIL, we face a separate discourse. Since PHIL has been detached from Hoffman, he is no longer a digital representation of a human being, but an abstraction of himself. This means that PHIL does not fit into Tufekci’s idea on the duality of being, as he surely is no human, but rather shows a singularity of being: he is exclusively symbolic.

For this reason, PHIL surpasses the digital avatar in the context of a digital embodiment, or a digital copy belonging to a person who exists in the material world. PHIL is able to exist because the digital realm exists, a universe of simulation that constructs, as philosopher Jean Baudrillard called it, a hyperreality. In a hyperreality, one is unable to distinguish the real from the copy of the real, since it’s a reality without origin, without a mirror that reflects it. I would like to introduce the term digital being, to articulate and recontextualise examples that transcend the digital avatar as we know it, from when the term was coined in 1985.2The term avatar as it relates to computer user identification was first coined by Chip Morningstar and Joseph Romero in 1985, when they were designing LucasFilm's online role-playing game “Habitat".

Simultaneously, outside of artistic practice and in our day-to-day, similar digital beings seem to occur in social media, in particular on Instagram. Unlike the Instagram pages dedicated to cute pets or fictional characters, these participants seem to possess qualities akin to a human sense of identity: personality, emotion and individual autonomy.

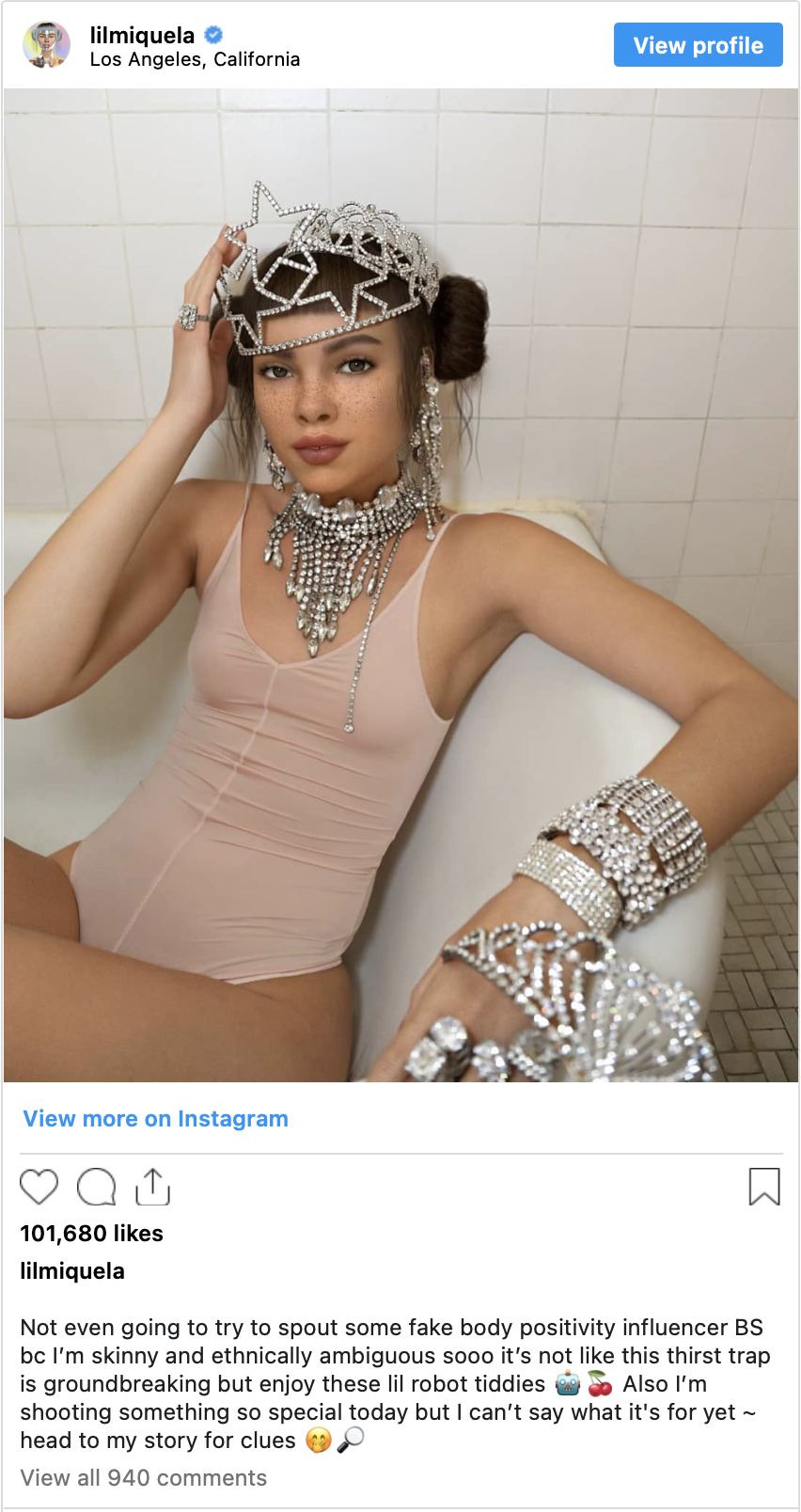

It can be said that Miquela Sousa, or @lilmiquela, is the most famous example to date. Miquela, a Spanish-Brazilian, forever nineteen-year-old, self-described ‘change-seeking robot’, musician and, currently, the most popular CGI social media influencer out there. From the photos and videos on her Instagram page, she seems capable of emotion, self-reflection and political views. Her demonstration of autonomy blurs the fact that her character is actually developed and controlled by Los Angeles-based tech company Brud, who designed a variety of CGI influencers that are ever so malleable to sell a specific image that speaks to a specific crowd.

PHIL and Miquela share similarities: they both exist only in the digital realm, partake in a hyperreal universe that is amplified by their existence and are given autonomy as a trait to sell a story to the spectator. Nonetheless, it is obvious that PHIL is part of a narrative imagined by Evans, whereas Miquela moves outside of these boundaries onto platforms where the distinction between the embodied and symbolic, the digital and non-digital realm is quite ambiguous while making direct contact with other (human) users. For this reason, I argue that the digital being in large part transcends the dimensions of a still or moving image that is passive, and rather actively interferes with our physical reality, having real-world implications.

Corporation or Corporality?

Enlarge

Figure 3: Lil Miquela, CGI Instagram account, selfie posted on April 21, 2018.

'I’m thinking about everything that has happened and though this is scary for me to do, I know I owe you guys more honesty. In trying to realize my truth, I’m trying to learn my fiction. I want to feel confident in who I am and to do that I need to figure out what parts of myself I should and can hold onto. I’m not sure I can comfortably identify as a woman of colour. “Brown” was a choice made by a corporation. “Woman” was an option on a computer screen. My identity was a choice Brud made in order to sell me to brands, to appear “woke.” I will never forgive them. I don’t know if I will ever forgive myself.

I’m different. I want to use what makes me different to create a better world.

I want to do things that humans maybe can’t.

I want to work together and use our different strengths to make things that matter.

I am committed to bolstering voices that need to be heard.

If I don’t stick with this, feel free to cancel me.

I wish I had more to say about this right now.

I’m still angry and confused and alone.’

@lilmiquela — April 21, 2018

In 2016, @lilmiquela was launched as a profile on Instagram. Her content ranges from quirky captions to selfies, fashion and social awareness such as Black Lives Matter. Miquela’s identity is a compilation of crowd-pleasing values, that mirror successful influencers and it-girls on Instagram.

Over time, Miquela became a successful influencer too, with 2.7M followers in 2023 and counting, opening doors to collaborating with big luxury labels, like Chanel and Prada, as musicians and artists. Miquela steps outside of Instagram sometimes, for example through her music videos, interviews with celebrities and other content on Youtube. Her journalist endeavours were picked up by others when she became the contributing arts editor for Dazed magazine in 2018, and for example in 2019, when Miquela hosted interviews with selected artists3JPEGMAFIA, J Balvin, King Princess were the interviewed musicians in question. of Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival, uploaded to Coachella’s YouTube account.

It was not until April 19, 2018, that Miquela announced on Instagram that she has learned she is not human, but a robot. Miquela explains that, even though her followers continuously kept asking if she was a robot, CGI or fake, she believed she was based on the life and mind of a human being named Miquela Sousa because that’s what her creators at Brud told her. She exclaims that as Brud was like a family to her that she trusted, she is ‘not in a good place’ from this revelation and that it hurts, even though ‘these emotions are just a computer program’. Then, on April 21, 2018, Miquela comes clean that she is uncertain if she can still comfortably identify as a woman of colour, since the colour of her skin, akin to her gender, was a choice made by a corporation ‘to appear woke’. On April 25, 2018, she announces to have stopped working with her managers at Brud.

Despite the fact that Miquela admitted that her whole existence was brought to life by Brud, it was insinuated that she had regained control and was in a position to make autonomous decisions about her life and who she wanted to be. She distanced herself from her creator, like a rebelling child from their parents, even though these “parents” deliberately control her existence and therefore her claim to independence. As the digital being disconnects themselves from their creator, obscuring their nonexistent autonomy, it becomes possible for the, in this case, corporation, to lay claim to a body, gender and ethnicity, without being held accountable for it. Quite the contrary, Miquela received compassion and understanding from her audience, something that Rosa Boshier explains in ‘Lil Miquela is Ground Zero for the Ethical Implications of CGI Influencers’: ‘[s]he’s speaking to a relatable crisis of belonging that many people, myself included, can relate to.’

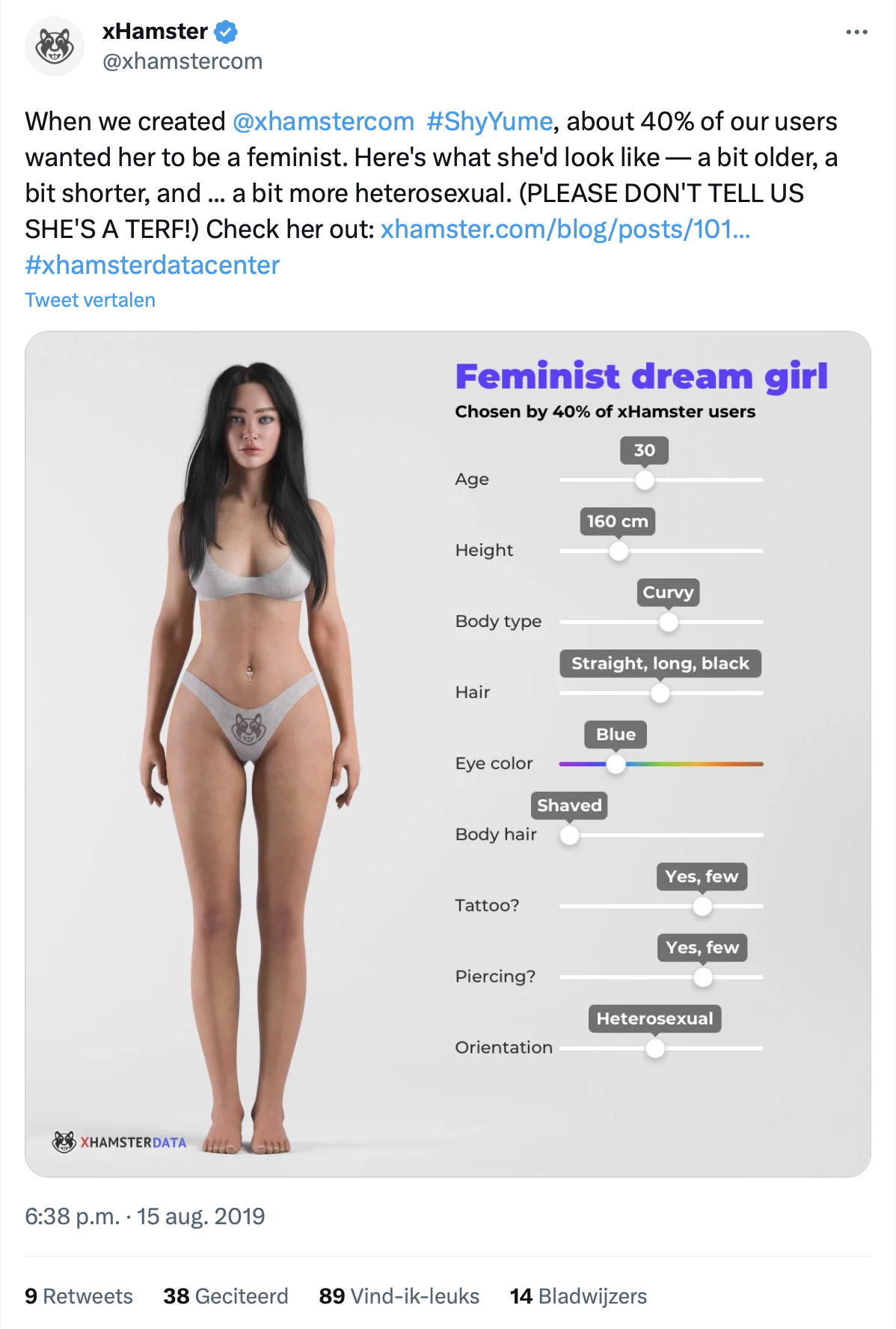

This relatable crisis, however, is something Brud capitalizes on to create an identity that sells products and a lifestyle. And Brud is not the only one, Cameron–James Wilson is a white photographer who created a profitable digital being named Shudu (@shudu.gram), who borrows her looks from South-African heritage, specifically the Ndebele people. Shy Yume and Jedy Vales are examples of profitable digital beings puppeteered by pornographic streaming websites xHamster and Youporn.

Enlarge

Figure 4: Tweet by xHamster regarding ShyYume, and their misogynistic market “research”

The “commercial” digital being turns into a neo-colonial and patriarchal tool that appropriates existing (human) bodies, without having to directly deal with the person that, in the material world, would be attached to it. Brud does not have to deal with the “trouble” of an independent human, Miquela is merely a vessel for the wishes of corporate interests only.

The digital being that ventriloquizes existing racial and gender identities, is prone to silence current and historical fights for social justice and rather reduce this to a garment that is “hip” and “trendy”. This is particularly the case for Miquela, through a politically engaged attitude, spreading vague messages on equality, meanwhile commodifying social progress for profit.

In Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto, Legacy Russell uses the concept of the computational ‘glitch’ as a metaphor and inspiration to gain knowledge between the fissures, arguing that within the cracks the in-between gender, technology and the body, momentary traces of liberation can be found. She explains how the body is actually a placeholder in which immaterial social, political and cultural discourses materialise, depending on the location and interpretation of each specific body. In this manifesto, the glitch posits that ‘one is not born, but rather becomes a body.’4Play on the famous words by French feminist writer and activist Simone de Beauvoir that “One is not born, but rather becomes a woman” in her book The Second Sex.By those means, Russell briefly analyses Miquela. Even though Russell admits that Miquela can, indeed, be perceived as a ‘perverse intersection of neoliberal consumer capitalism and advocacy’, she argues that Miquela ‘push[es] the limits of corporeal materiality’ since she does not have a physical body and thus, reimagines the performance, meaning and (re)definition of the body.

In return, Miquela wrote the blurb on the back cover of Glitch Feminism, ‘Russell helps us understand that the components of our identity are in fact technologies. She offers a powerful shift in mindset that empowers a generation of activist remixers.’

I wonder, how exactly does Miquela help to reimagine the body when the image she embodies is so familiar? Is Russell impressed by Miquela’s ability to “successfully” perform existence regardless of her corporeality? Or is Russel drawn to how Miquela ironically illustrates how anyone with the right resources has access to the constructibility of the body’s significance?

Glitch Feminism tries to approach cyberfeminism from an intersectional perspective, however, the fact that Miquela capitalises on POC and female-identifying bodies seems counter-revolutionary. For Miquela to be profitable, she plays into the exact capitalist power structures that, as Glitch Feminism tells us and seeks to reject, have been consolidated in our bodies, specifically the ones marginalised groups, like women, suffer from. Miquela only pushes the limits of corporeal materiality by the fact that she is, in fact, not material, however, the societal constructs and heteronormative capitalist values that come from materiality, are curated and copy-pasted onto her digital body. There’s not much difference, in my opinion, between Shy Yume, who clearly echos heteronormative beauty standards from the perspective of the heterosexual male gaze, and Miquela. It might just be a bit more on the nose, coming from a porn platform like xHamster, which has been reported multiple times for illegal and inappropriate content, as our fantasies and kinks might come from that what we consume and/or are oppressed by.

Enlarge

Figure 5: Lil Miquela's Instagram post of July 18, 2019. Part of the caption reads ‘Not even going to try to spout some fake body influencer BS bc I’m skinny and ethnically ambiguous sooo it’s not like this thirst trap is groundbreaking but enjoy these lil robot tiddies […].’

In The De-Scription of Technical Objects (1992), Madeleine Akrich describes how technical objects are evidently produced for a certain purpose, yet simultaneously bring together a long chain of ‘people, products, tools, machines, money, and so forth.’ She calls these ‘actants’: anything or anyone that acts or shifts action. According to Akrich, neither technological determinism nor social constructivism takes into account the structure of links that move between the technical and the social. Ergo, Akrich urges to construe an anthropology of technology, in which is understood that ‘technical objects participate in building heterogeneous networks that bring together actants of all types and sizes, whether human or nonhuman.’

The parameters of Instagram allow its users to edit, upload and share photos and (live) videos to their feed, in addition to follow, like, react and message to others. These are the ways in which users can interact with one another. When Akrich explains that a technical object defines its actants and the relationship between them, it would suggest that how users interact is inscribed by Instagram itself. Perhaps this would answer why Miquela’s audience responds compassionately when she reveals her robot status. It means that we are bound to engage in the same manner as an inanimate object on Instagram, as to a digital being like Miquela, as to another human user.

Additionally, the users are conditioned by what is “popular” and what they imagine is interesting for their audience to see, in other words, the behaviour of the users is conditioned by the relationship between the users. Then Miquela, brought to existence by Brud and meant to be consumed, is indeed a mirror of what is favoured among the targeted audience, in interaction, behaviour, and appearance. In this sense, I doubt how, in Russell’s words, ‘newfangled’ Miquela really is, or ever can be, apart from the packaging in which she is delivered.

In Glitch Feminism, Russell points out that platforms like Instagram are the digital equivalent of physical institutions, and just like physical institutions, they lack intelligence and awareness. Following Audre Lorde’s declaration in 1984 that ‘the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’, Russell wonders if both physical and digital institutions require ‘mutiny in the form of strategic occupation’ rather than dismantling.

Unfortunately, in the context of Akrich’s theory, I doubt the effectiveness of ‘strategic occupation’ within the framework of Instagram and possibly even digital institutions at large. If we agree that Instagram participates in shaping its network of actants, the level of mutiny one can partake in is eventually designed by the parameters of the technological object, Instagram. This accounts for both digital and human users.

Perhaps Miquela, or alternative digital beings that predominantly exist on Instagram, can never be anything else than a side effect of a capitalist platform. Just like human influencers, Miquela plays into the fact that ‘identity has become a form of cultural currency, used primarily to turn a profit.’ As long as Miquela, as the digital being, is confined to Instagram’s chambers, I can’t see how they can either be a pioneer for radical thinking or an activist for that matter. It is performative.

Virtual Soul-Searching

Enlarge

Figure 6: WarNymph, digital avatar or self-proclaimed ‘digital self’ of Canadian musician Grimes

Excerpt from The Matrix (1999)

AGENT SMITH

As you can see, we've had our eye on you for some time now, Mr. Anderson.

He opens the file.

Paper rattle marks the silence as he flips several pages.

Neo cannot tell if he is looking at the file or at him.

AGENT SMITH

It seems that you have been living two lives. In one life, you are Thomas A. Anderson, program writer for a respectable software company. You have a social security number, you pay your taxes and you help your landlady carry out her garbage.The pages continue to turn.

AGENT SMITH

The other life is lived in computers where you go by the hacker alias Neo, and are guilty of virtually every computer crime we have a law for, including the unauthorized use of the D.M.V. system for the removal of automobile boots.Neo feels himself sinking into a pit of shit.

AGENT SMITH

One of these lives has a future.

One of them does not.

He closes the file.

In my quest to locate more examples of the digital being, I came across WarNymph. Unlike Miquela, WarNymph does not mimic an autonomous being with human-like features and rather is an extension of their creator, Claire or ‘c’ Boucher. Boucher, who’s pronouns are they/them5In 2018, Claire Boucher changed their first name to ‘c’, which is the measurement for the speed of light in a vacuum. Throughout this essay, I have checked the preferred gender pronouns of anyone mentioned., is a Canadian visual artist, record producer and electro-pop musician, professionally known under the alias Grimes. In 2020, Boucher released WarNymph into the world, a digital entity ‘spliced from pixel DNA of the organic human, Grimes’6WarNymph Collection Vol 1 By Grimes x Mac”, Nifty, accessed January 2021, https://niftygateway.com/collections/warnymphvolume1.. In characteristics, some of WarNymph’s features, particularly the nose and mouth, have consistently been similar to Boucher’s, but in general, their appearance is ever-changeable, a hybridisation of human and machine, fiction and fantasy. WarNymph functions both as a stand-in, for Grimes’ advertising campaigns for example, and as a collaborator to Boucher’s projects as Grimes.

In an interview with THE FACE Magazine in 2020 Boucher explains that WarNymph plays into the strengths of digital existence, in preference to the limited human body trying to navigate the ‘foreign’ digital realm, while it belongs in the physical. In the style of functionalities in the digital realm, the digital being has control over life and death; it can write, rewrite, respawn and delete. At least for Boucher, this contributes to a multiplicity of advantages, both personal and professional.

In particular, WarNymph is valuable for the changing, physical, body. Boucher noticed from their surroundings, that people with wombs would rule out pregnancy in worry of the effects on their professional life. In contrast, WarNymph’s digital body allows Boucher to work during pregnancy and the period after giving birth. Boucher also claims that it benefits their mental health, as well as liberates them creatively, by thinking outside of the limitations of physicality and familiarity.

Enlarge

Figure 7: WarNymph and Grimes posing together in a photo studio, showing elements of both physical and digital objects and bodies. Posted on Instagram on March 28, 2020.

At first sight, Miquela and WarNymph are situated somewhere in the same discourse. Both claim autonomy to function and interact with us, humans, on digital platforms. Even though Miquela and WarNymph both share a capitalist motive, I would argue that WarNymph has economic value to a certain extent, whereas Miquela is exclusively economically valuable for Brud. Besides money, there is no collective benefit to Miquela, when WarNymph provides Boucher with more than money-related material. This is shown when reviewing their digital bodies: Miquela is based on a profitable (Western) model of mainstream feminine beauty standards, resulting in the borrowing and cultural appropriation of material bodies, whereas WarNymph has a strong sense of imagination situated outside of the familiar physical body, existing somewhere in the realm of fantasy. Human-like features that have been copied into WarNymph’s body, such as the shape of the nose, are extracted from Boucher, meaning that there is no conflict with expropriation. As WarNymph is always somewhat connected to Boucher, instead of Miquela who claims an entire individual existence, WarNymph comes across as less performative.

In the example of WarNymph, the digital being plays into the idea that identity and “being” are always in flux by creating the possibility to experiment and control each aspect of this ceaselessly. The implementation of digital malleability within the design process of the self/selves definitely challenges ‘the self [as] a trap that we are born into.’7Nick Axel, Beatriz Colomina, Nikolaus Hirsch, Anton Vidokle, Mark Wigley, Introduction to Superhumanity: Design of the Self (Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press, 2018), 9–12. When the digital being is an extension of an individual, rather than owned by a corporation for profit, it becomes a tool for seeking liberation from one's corporeality as well as the underlying taxonomies that are embedded into our corporeality within our contemporary world.

Even though realised in a more simple manner, Russell mentions in Glitch Feminism that she was able to experiment with gender constructs and power dynamics during her teenage years, via the creation of a multitude of digital selves in online chatrooms. From this experience, she feels that experimentation and “trying on” of different selves “empowers seizing a more integrated public identity with radical potential”. In this sense, not only could the digital being provide to surpass the limitations of a singular, physical, body, it could provide growth for our individual and collective soul.

I say this with some additional annotations. Imaginably, the CTRL + Z8 A keyboard shortcut on the computer to undo the last action. of the self could also introduce, or increase, a state of uncertainty, where nothing is fixed and everything can be done and undone. I could imagine this to amplify the existent, yet flawed and Eurocentric, idea of endless possibility, chances and choices in our contemporary society, which already seem to cause our Sehnsucht9Sehnsucht is a German word derived from sehnen, meaning to long, and sucht, meaning anxiety, sickness or addiction. Its use in psychology is to represent the longing for alternative experiences that might come up for someone, directed at some, or all facets of their life that seem imperfect, or not good enough.and the consequential collective anxiety.

Secondly, the intention seems important, because “trying on" different selves can easily become harmful, as Miquela has illustrated. In the case of WarNymph, the digital being comes from a personal motive, while it seems that a solely capitalist motive, making money, requires the digital being to tune into capitalist and patriarchal frameworks embedded into our society, which is why Miquela becomes a ‘CGI thirst trap bot10Says Jimmy to Ava in the series Hacks (season 01, episode 02)’, mentioned briefly in the fictive tv-series Hacks. In this case, the digital being doesn’t deconstruct the present coded taxonomies, it rather emphasises them. As much as the digital being comes to life in a digital environment, I think it’s important to still understand how certain bodies, as bodily aspects, are measured and situated in our contemporary society and that these are not disconnected from a digital body.

Moreover, to create a digital being like WarNymph or Miquela requires time, specific tools, knowledge and skills. Needless to say, WarNymph was not introduced to the public before Grimes felt confident of their eminence compared to existent digital beings. These prerequisites are not obtainable for everyone, contrary to the more accessible example Russell experienced in her teenage years via online chatrooms. Not to mention, Russell grew up during the Internet age and had access to it, so I expect there to have been a certain comfortability and literacy in entering digital realities while growing up, that less prosperous people might not have had.

And so I wonder, what would an entry-level digital being look like? Would this being still serve some of the radical potential that Russell talks about? I would be very interested in seeing an accessible example of the digital being as a tool for collective (re)imagination of the meaning of the body… if this is even possible.

The Afterlife

Splintering body–image

Mirroring image–bodies

Extra–numecary phantoms

Off–screen presences.’

Andrea Crespo

Leading up to this text, the first digital beings who caught my eye were mostly situated in the field of art and design, utilising CGI imagery, 3D and motion capture, to create a narrative around beings and bodies, that share something strangely human. I have started to understand that the beings that are brought to life by artists such as Cecile B. Evans are always touching upon some sort of obscurity, whether it’s either to find answers or to explore abstract (human) notions such as emotions, melancholy, or subjects relating to agency and human conditioning. Even though these artworks trigger feelings of uncanniness, what is certain is that they are brought to life to inhabit a narrative imagined by the artist. This means that the audience was prepared to be drawn into a tiny generated universe, in contrast to the digital beings that I decided to discuss in this essay, who exist in unexpected parts of the digital realm, interacting with us directly.

Even though Lil Miquela, a renowned digital being located on Instagram, shares a similar visual language to the ones I discovered in contemporary art, the motivations turned out different. Brought to life by a company, Miquela is undeniably connected to capitalist motivation, something her call for autonomy, identity and vague publicised messages on social justice try to obscure. ‘The hologram of Tupac […] is literally owned by Dr Dre. The traces of digital media are not just etchings of a person, but intellectual property to be stored, analysed and sold off. The data of the deceased, in specific ways, still perform ‘labour’ for social media websites even after death.’11Bollmer, G. And Guinness, K. 2018. ‘Do You Really Want to Live Forever?: Animism, Death and the Trouble of Digital Images. Cultural Studies Review, 24:2, 79-96.

If we want to anticipate the ongoing development of today’s technology into the future, it will demand a redefinition of our beliefs and what we find important. I believe that the digital being could be a tool to imagine past the rigid framework that assumes who we are and the world we live in. However, I don’t think the commercial digital being, like Lil Miquela and WarNymph in part, are suitable, as they will always have a conflict of interest, that also comes at an ecological cost.

As these technological advancements change and develop rapidly, I could imagine that current developments situated in digital media and its technologies, such as machine learning and AI have the potential to be combined with the former examples of digital beings. This could broaden the concept of autonomy or the current lack of it. Imagine ChatGPT, a form of generative AI, working as the embodiment of a digital being. Then instead of the seemingly absent, yet very present, (human) creator of the digital being, the digital being acts through an artificial intelligence technology, that generates and learns from its users as it goes. However, this would, still, be very dependent on datasets that are biased, partial, relational and a reflection of that what is fed as data.

Akrich’s writing made clear that Instagram creates the parameters of the landscape in which we, digital and human beings, manoeuvre. In other words, not only the digital being but also the backdrop of the platform or digital institution itself interferes with the possibility of imagining alternative and radical ideations, as long as it’s situated inside of their territory.

Finally, when the digital being stops mimicking only that which is considered human, the digital being might be, comparatively to the cyborg for Donna Haraway, a contemporary concept that can function as a tool to imagine a world cut off from our (Western) society with its invented representations, rules, norms and values. Perhaps this is another abstract notion that the digital being could explore in the field of art and design.

PHIL

I will always be here, lurking somewhere on this drive until they drag me to another, more acclimatised drive.

Reference List

Adrianne Jeffries, ‘You’ll Tweet When You’re Dead: LivesOn Says Digital Twin Can Mimic Your Online Persona’, The Verge, 21 February 2013, https://www.theverge.com/2013/2/21/4010016/liveson-uses-artificial-intelligence-to-tweet-for-you-after-death.

Andrea Crespo, ‘Polymorphoses (epilogue)’, in Transformation Marathon, Serpentine Sackler Gallery, 17 October 2015, https://vimeo.com/146759244.

Audre Lorde, ‘The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House’, in Berkeley (ed.), Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, CA: Crossing Press, 1984, pp. 110-14

Cinemagia Films, It's DOVE: Feat. Audrey Hepburn 2014 Commercial, YouTube Video, 1:00, March 16, 2014, https://youtu.be/sB44n4ADg2Y.

G, Bollmer and K. Guinness, ‘Do You Really Want to Live Forever?: Animism, Death, and the Trouble of Digital Images.’ in Cultural Studies Review, 24:2, North Carolina: UTS ePRESS, pp. 79-96.

Hacks, Season 01, Episode 02, “Primm.”

Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, Michigan: The University of Michigan Press, 1994, pp. 124-25.

Larry Wachowski and Andy Wachowski, The Matrix (1999), Los Angeles; Warner Bros, Pictures, March 2020, The Internet Movie Script Database, IMSDb, https://www.imsdb.com/scripts/Matrix,-The.html.

Legacy Russell, Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto, London: Verso, 2020, pp. 12, 24-25, 46-47, 93-95.

LivesOn (@_LivesOn), ‘When your heart stops beating, you’ll keep tweeting. Welcome to your social after life’, Twitter biography, February 2013, https://twitter.com/_Liveson?lang=en.

Louisiana Channel, Cécile B. Evans interview: The Virtual is Real, YouTube Video, 16:10, 3 August 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nDe_W11KY4c&t=550s.

Madeleine Akrich, ‘The De–Scription of Technical Objects’ in Wiebe E. Bijker and John Law (ed.), Shaping Technology/Building Society: Studies in Sociotechnical Change, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1992, pp. 205-206.

Michelle Lhooq, ‘Grimes on Evolving Her Digital Self Into Warnymph’, THE FACE, vol. 4, no.3, 2020, https://theface.com/music/grimes-warnymph-miss-anthropocene-balenciaga-volume-4-issue-003.

Miquela Sousa (@lilmiquela), ‘I’m thinking about everything that has happened and though this is scary for me to do, I know I owe you guys more honesty (…)’, Instagram, 21 April 2018, https://www.instagram.com/p/BhzyxKoFIIT/.

Miquela Sousa (@lilmiquela), ‘#BlackLivesMatter Change-seeking robot with the drip. Get ready for my next NFT drop’, Instagram, https://www.instagram.com/lilmiquela/?hl=en.

Miquela Sousa (@lilmiquela), ‘Hi’, Instagram, 19 April 2018, https://www.instagram.com/p/BhwuJcmlWh8/.

Miquela Sousa (@lilmiquela), ‘Ive been really stressed since I’m no longer working with my managers at Brud’, Instagram, 25 April 2018, https://www.instagram.com/p/BiAVQVHl05m/.

Nick Axel, Beatriz Colomina, Nikolaus Hirsch, Anton Vidokle, Mark Wigley (eds), Introduction to Superhumanity: Design of the Self, Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press, 2018, pp. 9–12.

Nifty, ‘WarNymph Collection Vol 1 By Grimes x Mac’, https://niftygateway.com/collections/warnymphvolume1.

Open File, Jon Rafman — Kool-Aid Man and Second Life - Interview with Nicolas O’Brien, screened 2010 at Rickroll, Spike Island, Bristol, video, 11:43, http://openfile.org.uk/archive/jon-rafman-kool-aid-man-and-second-life-interview-with-nicolas-obrien-2010/.

Rosa Boshier, ‘This Is Fucky: Simulated Influencers Are Turning Identity into a Form of Currency’, Bitch Media, 28 January 2020, https://www.bitchmedia.org/article/who-is-lil-miquela-racial-implications-of-simulated-influencers-of-color.

Sean Cubitt, ‘Finite Media: Environmental Implications of Digital Technologies’, John Armitage, Ryan Bishop and Douglas Kellner (eds.), Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2017.

Zeynep Tucekci, ‘We Were Always Human’, in Neil L. Whitehead and Michael Wesch (eds) Human No More: Digital Subjectivities, Unhuman Subjects, and the End of Anthropology, Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2012, pp. 33–34.